Editor’s note: The following article was written by Fr. Michael Oleksa, the foremost historian of Orthodoxy in Alaska, retired dean of St. Herman’s Seminary, and member of SOCHA’s advisory board. The article originally appeared as a chapter in Fr. Michael’s fascinating book, Another Culture / Another World (Association of Alaska School Boards, 2005). Fr. Michael has graciously granted permission for SOCHA to reprint the chapter here at OrthodoxHistory.org.

In 1794, the first group of Christian missionaries to work in Alaska arrived on Kodiak, having walked and sailed over 8,000 miles from Lake Ladoga, on the Russian border with Finland. One of the priests in this delegation of ten monks, a 35-year-old former military officer, Father Juvenaly, was assigned the task of visiting and preaching among the tribes of the southcentral mainland. He began at Kenai, headed northward through what is now the area surrounding Anchorage, then down the western coast of Cook Inlet, across to Lake Iliamna, and out to the Bering Sea.

His journey would bring him from the biggest lake in Europe to the biggest lake in Alaska. But soon after he departed for Iliamna, he disappeared. No one ever heard from him again. Rumors reached Kodiak that he had been murdered, but there were no eyewitnesses or any other conclusive evidence of his whereabouts for several decades.

Then, about a hundred years later, an American historian, Hubert Bancroft, published an account of Father Juvenaly’s death purportedly based on the priest’s own words as he recorded them in a diary that a man named Ivan Petrov claimed to have found and translated. According to this diary, Father Juvenaly fell into temptation, having been seduced by the daughter of a local Indian chief, and then was hacked to death for refusing to marry her.

That is all I knew about this incident until my Yup’ik father-in-law, Adam Andrew, who was born about 1914 in the mountains near the source of the Kwethluk River, decided to tell me the story about “the first priest to come into our region.”

According to my father-in-law, this first missionary arrived at the mouth of the Kuskokwim, near the village of Quinhagak, in an “angyacuar,” a little boat. He approached a hunting party led by a local angalkuq (shaman) who tried to dissuade the stranger from coming any closer to shore. The Yup’ik tried to signal their unwillingness to receive the intruders, but the boat kept coming. Finally the angalkuq ordered the men to prepare their arrows and aim them threateningly at the priest. When he continued to paddle closer, the shaman gave the order and the priest was killed in a hail of arrows. He fell lifeless to the bottom of the boat. His helper (in Yup’ik, “naaqista,” literally “reader” — someone who supposedly assisted the priest at services) tried to escape by swimming away.

Jumping overboard, he impressed the Yup’ik with his ability to swim so well, especially under water. They jumped into their kayaks and chased the helper, apparently killing the poor man, reporting later that this was more fun than a seal hunt.

Back on shore, the shaman removed the brass pectoral cross from the priest’s body and tried to use it in some sort of shamanistic rite. Nothing he tried seemed to work satisfactorily. Instead of achieving its intended effect, each spell he conjured up caused him to be lifted off the ground. This happened several times until finally, in frustration, the shaman removed the cross and tossed it to a bystander, complaining that he did not understand the power of this object, but he no longer wanted to deal with it.

When I first heard this version of the story, I was dubious that such an incident could have occurred. I knew the first priest to come to the Kuskokwim had arrived in 1842, had served on the Yukon for nearly 20 years, and had died in retirement at Sitka in 1862. It did not occur to me that this was the oral account of the death of Father Juvenaly, until I later learned that the Bancroft/Petrov report was completely false — a fabrication of Mr. Petrov’s rather fertile imagination.

Hubert Bancroft, the preeminent American historian of his time, never came to Alaska and did not know Russian, the language in which all the earliest historical documents relating to Alaska were written. He hired Petrov to gather documents and translate them, but Petrov did not like Mr. Bancroft much and falsified a lot of data, creating entire chapters of what became the first history of Alaska from records that never existed.

Father Juvenaly’s diary was one of Petrov’s concoctions. This becomes obvious as soon as any informed scholar opens the manuscript, still housed in the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley. Juvenaly travels on ships that never existed, celebrates church holidays on the wrong dates and even the wrong months, and miraculously understands Yup’ik within a few weeks, while finding Kodiak’s Alutiiq language beyond his reach. These two languages are so closely related that speakers of one believe they can readily understand speakers of the other. Not knowing enouch about Russian Orthodoxy to spot glaring discrepancies, Bancroft accepted the diary as authentic, and used it as the basis of his chapter on the death of Father Juvenaly.

Once I realized the published accounts were bogus, I went back to my father-in-law for another telling of the Yup’ik version. We then started to hunt for corroborating evidence. I found that every visitor to Quinhagak in the last 70 years following Father Juvenaly’s demise mentioned in their reports that this was the site of the incident. I heard from people in the Iliamna area that their ancestors knew nothing of a priest being killed in their region, but only that one had passed through, heading west. I heard from the Cook Inlet Tanai’na Indians that a priest who had come from Russia via Kodiak had baptized them, then left heading in the direction of Iliamna. And I discovered that the people in the village of Tyonek have always had a great swimming tradition, and are still capable of diving into the ocean after the beluga wales that they hunt. The oral accounts among all the Native peoples of the region were consistent with my father-in-law’s story. But how to prove it accurate, one way or another?

Finally, another scholar discovered a passage in the diary of a later missionary resident of Quinhagak, Rev. John Kilbuck, written sometime between 1886 and 1900, indicating that the first white man killed in the region was a priest who had come upon a hunting party camped near the beach. After trying to dissuade the priest from approaching, and unable to turn him back, the hunting party killed him. His companion tried to swim away “like a seal” and was hunted by the Yup’ik, who had to resort to their kayaks to chase him. The same story that my father-in-law had told me was being told in the village a century after the actual incident.

I have friends whoh visit and students who reside in Quinhagak, as well as a nephew who lives there. I asked them if they had ever heard the story of how the first priest to visit there was killed. I discovered that the story is still known and told almost verbatim the way my father-in-law told it to me.

Contrary to popular misperception, the oral tradition of tribal peoples tends to be very accurate, for the most part ensuring that stories remain intact over time. The story is understood as community property, not the invention of the storyteller, and, unlike my eastern European family’s tendency to change a story to make a point, in groups whose histories are transmitted through the oral tradition, retellings tend to be more faithful to the original story.

However, after looking at my written summary of the story of Father Juvenaly as it had been told to me, one informant did tell me that in a version of the story he had heard, there was a detail I had not been told. According to the story as it had been given to him, just before the priest’s death, while standing up in his little boat, he appeared to those on the shore to be trying to swat away flies. At first, this seemed to me a strange detail to include. What did it mean? What was really happening? When someone is about to die, facing his attackers with their arrows pointed at him, why worry about insects?

Puzzled by the account, I kept returning to the scene in my mind until it occurred to me what may have been going on. The man in the angyacuar could have been either praying, making the sign of the cross on himself, or blessing those who were about to kill him — but so rapidly that to those on shore who had never seen anyone do this, it could well have looked like he was “chasing away flies.” This detail from the oral tradition is a perfectly believable addition to the story, and adds credibility to the story itself, as the Quinhagak people remember it.

After carefully looking at everything I could find on this incident, I sent a summary of my research to one of my university students from Quinhagak and asked her what she made of the incident. She replied, somewhat sheepishly, “Well, they didn’t know he was a priest!”

The question remained, though, why were these armed men so fearful of an unarmed stranger, whom they so vastly outnumbered? True, he was pale, tall, bearded, and oddly dressed. He likely appeared exotic, if not totally alien. But why would they have felt so threatened by his physical presence as to destroy him?

The answer may reside in the brass cross that he wore. We know from exhibits at the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C., that at that time shamans carved ivory chains in imitation of their counterparts on the Siberian coast, who wore metal chains. Wearing such a metal chain was an indication that the stranger had spiritual powers possibly superior to the local angalkuq. The only way to defend oneself from such alien magic would have been to kill the magician. So it seems that Father Juvenaly died in a case of mistaken identity.

This history lesson tells us that while historical texts may contain many useful details and important data, they can be wrong. Historians usually depend on what is left behind in the reports, diaries and letters of others, in order to piece together a description of another time and place, and it is easy to be misled, mistaken or fooled. Such was the case with the death of Father Juvenaly two hundred years ago. It has taken nearly two centuries to solve the mystery of his disappearance and death. Original published accounts were based on false and forged information, but the truth survived in the oral tradition of the Yup’ik people.

At least when dealing with the Native experience in this land, no one should dismiss the stories as the indigenous people tell them. In my experience, while the published texts have often proven unreliable, grandpa has always been right.

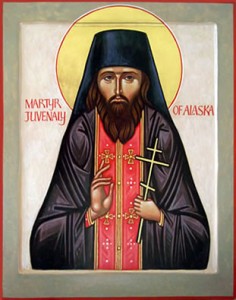

[This article was written by Fr. Michael Oleksa. To order a copy of Another Culture / Another World, click here. The icon of St. Juvenaly was painted by Heather MacKean, and is used courtesy of St. Juvenaly Orthodox Mission.]

5 responses to “The Fate of Father Juvenaly: A story from Yup’ik history”

Hello,

I am currently writing a curriculum on the Saints for my St. Stephen’s Course project with the Antiochian Archdiocese. St. Juvenaly is my patron, and I would like to use include him in this curriculum.

I would be happy to tell you more about the plan for the curriculum, if you so desire. The reason for my post here is to ask for permission to use the material from this post in the section on St. Juvenaly. Not all of it is relevant, but the actual story of his mission work and martyrdom is. How can I get permission to use some of this post?

Thank you.

You’ll want to contact Fr. Michael Oleksa. Visit his website, http://www.fatheroleksa.org, for contact information.

Thank you.

In Paul Garrett’s “Saint Innocent: Apostle to America,” in the second chapter of part one, page 29, Garrett quotes St. Innocent giving his own account of the martyrdom of St. Juvenaly. It is not completely dissimilar from the one Fr. Michael gives here. Although I don’t have St. Innocent’s journals in my library, it seems to me that I read in them (years ago) a more complete account of St. Juvenaly’s martyrdom, including the bit about the shaman trying to work magic on his pectoral cross. I could be wrong about that reference, but I feel like I read it there. If any of you have a copy of his journals, most of the entries are quite dry–mostly mundane stuff. If you scan them, however, the important things are usually much longer entries, and it is one of these that, I believe, gives his thoughts upon first hearing the account during his missionary travels. It also seems to me that the pectoral cross may have been returned by the natives to St. Innocent, having kept it for 100 years or more. Anyone able to corroborate any of this? Anyone have a copy of St. Innocent’s Diary / Journal, as published by the state government of Alaska?

[…] 1) http://45.77.159.119/2010/05/13/the-fate-of-father-juvenaly-a-story-from-yupik-history/ 2) https://www.oca.org/saints/lives/2016/09/24/102714-martyr-juvenal-of-alaska 3) […]