Last week, we left the two New York Syrian camps — Orthodox and Maronite — on the brink of war. Each side’s partisan newspaper attacked the other, and the Maronites took particular aim at St. Raphael, the Orthodox bishop of Brooklyn, accusing him of all sorts of outlandish offenses. Various parties received anonymous threats, and things came to a head in late August, when a Maronite group known as the Champagne Glass Club (CGC) told the police that St. Raphael had called on his followers to use violence against their Maronite enemies.

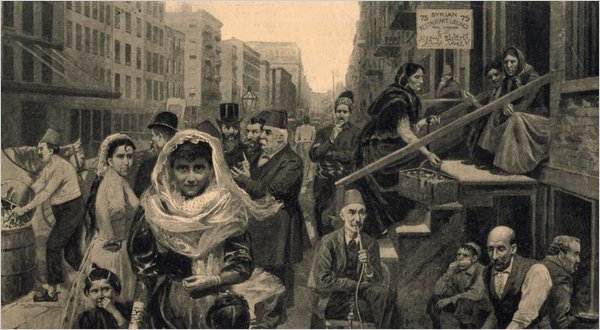

For the next few weeks, the Syrian community was balanced on the edge of a knife. The war of words continued in the papers, to the point that many Syrian men tried to forbid their wives from reading them. (Whether the wives followed this command is an open question.) The police seemed to think that this was all rather harmless, and even amusing.

That is, until September 15. That afternoon, about 20 Syrian men, representing both the Orthodox and Maronite parties, came to blows in the business center of the Syrian enclave. They were armed with guns and knives, but, thankfully, only one shot was fired, and it missed its target. A policeman bravely rushed into the fracas, breaking up the fight and arresting three men. One of the arrested Syrians, Haiss Nahas, had a slight head wound — the day’s only injury, caused when he was knocked to the ground by Navis Harris. Harris, for his part, claimed that Nahas has fired a shot at him.

Nahas, Harris, and another man were hauled into police court. Harris appears to have been Orthodox, and he was represented by the prominent attorney Charles Le Barbier. Just as the case came up before the magistrate, the other party — Nahas, he of the head wound — was brought in. Le Barbier’s jaw dropped when he realized that he had represented Nahas in a previous case, and thus had an unavoidable conflict of interest. Both prisoners were locked up, with bail set at $500 apiece. When another Syrian tried to bail out Harris, the police recognized him as one of the men involved in the fight. He was arrested, but was soon set free by the merciful magistrate.

The street fight took place in broad daylight on Friday afternoon, August 15, in the heart of the Syrian colony. But this incident was more of a skirmish than an actual battle. The combatants apparently took the weekend off, although St. Raphael reportedly accused Naoum Mokarzel, editor of Al Hoda and leader of the Maronite Champagne Glass Club (CGC), of attacking him in print (New York Times, 9/19/1905). This would hardly have been the first time Al Hoda had gone after Raphael, and the Times reference isn’t terribly clear, but it’s possible (probable, even) that St. Raphael addressed the controversy in his Sunday homily.

Anyway, come Monday, the Syrian colony was a powder keg. In my next article in this series, I’ll discuss full-blown outbreak of war that took place on August 18. Before I do that, though, I want to point out a few other facts that I haven’t yet mentioned, which contributed to the hostility in the Syrian colony.

One of the richest Syrian merchants in New York was a man named John Abdulnour (in fact, the Brooklyn Daily Eagle of August 19 describes him as “the wealthiest Syrian in America” and “the leader of the Syrians”). Abdulnour was apparently a Maronite, but his wife was Orthodox, and she would occasionally travel from their “palatial” home in Staten Island to attend St. Nicholas Orthodox Cathedral in Brooklyn. Late in the summer of 1905, Mrs. Abdulnour filed for a divorce — with the apparent encouragement of St. Raphael (Tribune, 9/20).

Another issue, which I’ve briefly touched on already, is the fact that St. Raphael did not simply remain silent in the face of slander. No, he didn’t call for vengeance like the CGC claimed, but he also didn’t just take the attacks lying down. According to the Eagle, Raphael sued a Maronite editor named Maloof for libel. The amount? $23,000 — that is, over half a million dollars today. Now, I wouldn’t be too harsh on St. Raphael, as libel suits were exceedingly popular at the turn of the last century. In any event, St. Raphael agreed to accept an apology and drop the case, but that did nothing to quell the ever-increasing resentment that each side felt for the other.

Finally, there is the issue of Lebanese nationalism. Of course, back in 1905, there was no state called “Lebanon” — today’s Lebanon and Syria were, at that time, still a part of the Ottoman Empire. But Naoum Mokarzel aimed to change all that. He was as passionate a Lebanese nationalist as there ever has been, and according to an article in Arab Studies Quarterly, he was directly instrumental in the eventual establishment of the Lebanese state. But Lebanese nationalism was far more of a Maronite sentiment than an Orthodox one, and Mokarzel no doubt felt that St. Raphael’s relative tolerance of the Ottomans and out-and-out loyalty to the Russians was a betrayal of his heritage. To Mokarzel and his ilk, all things were subordinate to the ideal of Lebanon; to St. Raphael, fidelity to one’s faith always trumped the idea of national identity.

As I said, in my next article on this subject, I’ll finally get to the big event — what one newspaper called the “Battle of Pacific Street” — and the resulting arrest of one of the greatest saints in American Orthodox history.

[This article was written by Matthew Namee.]