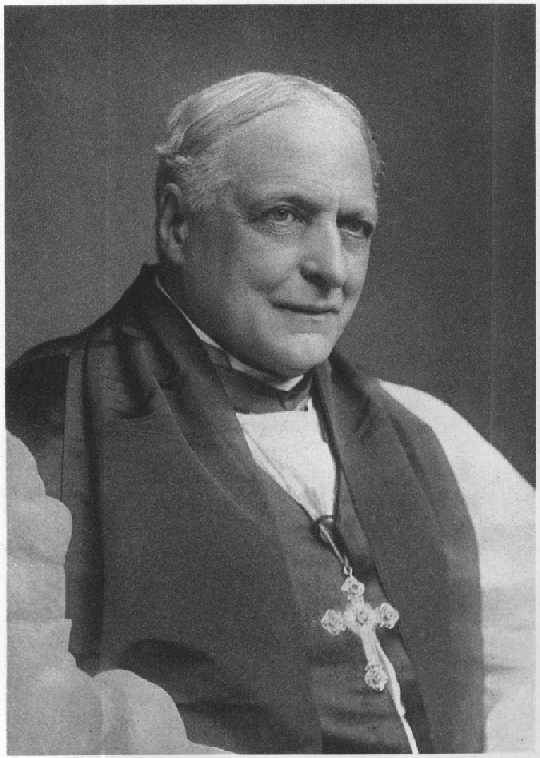

Bishop Charles C. Grafton

On November 5, 1905, St. Tikhon ordained Ingram N.W. Irvine an Orthodox priest. It was a courageous action, and I cannot help but think that St. Tikhon’s feelings on the matter were bittersweet. He knew — he must have known — that he was indeed ushering in a new “epoch in Church history,” as Irvine put it. He knew Irvine’s baggage, and Irvine’s dreams. He knew that Irvine would work for a distinctly American Orthodoxy, one in which English would increase and Slavonic would decrease. But more than that, he knew that by ordaining Irvine, he would irreparably damage the close relations he had built up with leading Anglicans, most especially his dear friend, Bishop Charles Grafton.

Bishop Grafton was a great man. He was the Episcopal Bishop of Fond du Lac, Wisconsin, but he was much more than that. He was the head of Nashotah House, one of the preeminent seminaries in the Anglican world (and in the very year of Irvine’s ordination, Nashotah House had awarded Tikhon an honorary doctorate). Grafton was also one of the leading lights of “Anglo-Catholicism,” that High Church part of Anglicanism which was most friendly towards Orthodoxy. In his long life — he was 75 when Irvine was ordained — Grafton had done as much as anyone to foster close ties with the Orthodox Churches, and virtually from the moment of St. Tikhon’s arrival in America in 1898, Grafton was a close friend and confidant. Grafton represented the very best that the Episcopal Church had to offer, and for Tikhon, his friendship was invaluable.

And Tikhon must have known that, in accepting Irvine, he would lose his friend. On November 4, 1905 — the day of Irvine’s chrismation and ordination to the diaconate — Grafton wrote in a letter, “I have been very busy this last week in the endeavor to stop Bishop Tikhon from ordaining Dr. Irvine to the priesthood on Sunday the 5th November.” He continued,

[Tikhon] is a good, gentle, pious Christian Bishop who has been imposed upon. For the sake of the Russian Church I am sorry it should take up with a man who rightly or wrongly has been deposed from the priesthood. There was no necessity for it, for Dr. Irvine could have appealed to the Court of Review lately established, or to the House of Bishops sitting, as they do, in Council. The action of Archbishop Tikhon can only be based on the view that we are no part of the Catholic Church and so all relations between us must terminate, or on the ground that he has received authority from the Holy Synod to receive appeals from our courts. In the latter case I said that we had received no notice of such authority being delegated, and if we had, and had accepted it according to the Canon of the Universal Church which he was bound to respect, he could only hear appeals from bishops and not from priests who were confined to appeals within their own nationality or province.

While well intentioned, Grafton was in error. Of course, his arguments display a fundamental ecclesiological misunderstanding: Grafton thought that the Orthodox and Anglican Churches were both parts of the “Catholic” (Universal) Church, and thus that the Orthodox had to respect the territorial rights and judicial decisions of the Anglicans. In Grafton’s (and the Anglicans’) view, St. Tikhon was roughly paralleled by the Russian Ambassador. Ordaining Irvine was equivalent to the Russian Ambassador declaring a convicted American criminal to be innocent, and then bestowing a Russian consulate on him. The Russian Ambassador had no such rights; he was in America for diplomatic purposes, but he had no jurisdiction here. The same basic restrictions applied to St. Tikhon, so thought the Anglicans.

Incidentally, Grafton also misunderstood his own Church’s appeals process. When Irvine was defrocked by his Episcopal bishop in 1900, the Episcopal Church had no mechanism by which he could appeal the punishment. They established a court of appeal in 1905, but that court was not able to make retroactive rulings. Irvine simply had no way of being reinstated in the Episcopal Church.

Grafton concluded his letter with strong words:

My telegrams will be published in next week’s Living Church; our presiding Bishop has protested. The Archbishop has made a big, bad blunder. I asked the Russian Ambassador to interfere with his influence. But I fear Tikhon will steer his craft on the rocks. My hope is that God will in some way overrule this to good, for it is Satan’s work.

Neither God nor the Russian Ambassador prevented Irvine’s ordination. Richard Hatfield — than an Episcopal priest, but now Fr. Chad Hatfield, the chancellor of St. Vladimir’s Seminary — wrote in 1992, “The friendship between Grafton and Tikhon ended with the ordination of [Irvine]. … The ordination of Father Irvine brought to an abrupt close the first phase of Orthodox-Anglican relations in the new world.”

Perhaps Anglican “branch theory” that there are three branches of the Church, namely Orthodox, Catholic, and Anglican, may seem stranger than Rome’s way of approaching reconciliation, but one of the things I pointed out in An open letter to Catholics on Orthodoxy and ecumenism is that for all their efforts at reconciliation, I have never once heard a Catholic who was reaching out even acknowledge Orthodox concerns about recantation of Western heresy as a basis for any proper reunification.