At the turn of the last century, relations between the Orthodox and Anglican Churches were quite warm. They cooled a bit in 1905, when St. Tikhon ordained the former Episcopal priest Ingram Nathaniel Irvine to the Orthodox priesthood, but even so, many on both sides of the dialogue felt that full union would eventually happen.

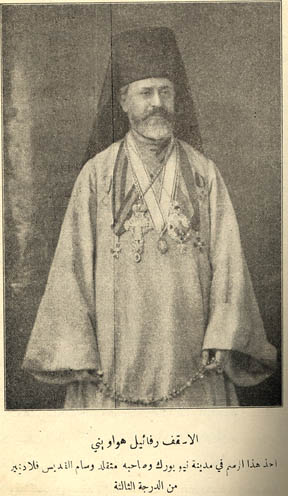

In England in 1896, a body was formed called the “Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union.” A dozen years later, in 1908, a group of High Church Episcopalians decided to establish an American branch of the organization. Several Orthodox leaders attended the first meeting in New York City, including the Syrian Bishop Raphael Hawaweeny and two of his clergy, the Fr. Benedict Turkevich (representing the Russian Archdiocese), and Fr. Methodios Korkolis (representing the Greeks). During the meeting, St. Raphael was elected to be the Orthodox Vice President.

The Episcopalians had an ambitious agenda: they wanted the Orthodox to recognize their holy orders as valid; indeed, they wanted to be recognized as a Local Church, just as “Orthodox” as Russia or Antioch. The Orthodox, and St. Raphael in particular, had much more modest goals. They wanted to promote friendly dialogue, with initiatives such as seminarian exchanges.

All the while, St. Raphael faced a monumentally difficult pastoral situation. His flock was scattered across North America, and many lived far away from any Orthodox church, Syrian or otherwise. In 1909, the Episcopalians suggested that he have the Anglican Book of Common Prayer translated into Arabic, so that the Syrians could worship with the Episcopalians. Raphael responded that it would be better for the Episcopalians to buy some Orthodox service books for their churches, so that the Syrians could use them if they visited.

In June of 1910, Raphael went even further, granting formal permission for his people to seek the ministrations of Episcopal clergymen in the event that no Orthodox priest was available. Here is his letter, which I am reprinting from the Journal of the Proceedings of the One Hundred and Ninth Annual Convention of the Protestant Episcopal Church in the Diocese of New Hampshire (November 1910):

Right Reverend and Reverend Brothers:—

I thank God for the great work which is being done by our Union, in the way of promoting fellowship and a better understanding between the Holy Orthodox and Anglican Churches.

I assure you also of my full appreciation of all the kindnesses and courtesies extended to me and my people.

Now, in order that all complications may be avoided in the matter of mixed Services, that is, when a Syrian Orthodox may desire to have any Sacrament performed by a Bishop or Priest of the Anglican Communion in North America, I offer briefly some of our rules, as Orthodox Catholics, which, if possible, I beg to have enforced.

However, in this matter I am only speaking for myself personally, as an Orthodox Bishop, and in no way binding my brother Orthodox Bishops in North America. I speak alone for the Syrian people.

First:—It is against our Law to marry two brothers to two sisters.

Second:—It is equally contrary to the same law to marry a man to a deceased wife’s sister, and vice versa.

Third:—We do not permit marriage within the fourth degree of consanguinity.

Fourth:—Civil Divorces are not acknowledged by the Orthodox Church, unless for causes she sanctions; and, therefore, no civilly divorced person can be reunited in wedlock to another party, unlets divorced by the Church, as well as by the State.

Fifth:—The Orthodox Church requires that a child shall be baptized by a Trine Immersion in the water, and be immediately afterwards Chrismated.

Inasmuch as there is a variance between your and our Churches in these matters, I suggest that, before any marriage Service is performed for Syrians desiring the services of the Protestant Episcopal Clergy, where there is no Orthodox Priest, that the Syrians shall first procure a license from me, their Bishop, giving them permission, and that, where there is a resident Orthodox Priest, that, the Episcopal Clergy may advise them to have such Service performed by him.

Again, in the case of Holy Baptism, that, where there is no resident Orthodox Priest, that the Orthodox law in reference to the administra

tion of the Sacrament be observed, namely immersion three times, with the advice to the parents and witnesses that, as soon as possible, the child shall be taken to an Orthodox Priest to receive Chrismation, which is absolutely binding according to the Law of the Orthodox Church.

Furthermore, when an Orthodox Layman is dying, if he confesses his sins, and professes that he is dying in the full communion of the Orthodox Faith, as expressed in the Orthodox version of the Nicene Creed, and the other requirements of the said Church, and desires the Blessed Sacrament of the Body and Blood of Christ, at the hands of an Episcopal Clergyman, permission is hereby given to administer to him this Blessed Sacrament, and to be buried according to the Rites and Ceremonies of the Episcopal Church. But, it is recommended that, if an Orthodox Service Book can be procured, that the Sacraments and Rites be performed as set forth in that Book.

And now I pray God that He may hasten the time when the Spiritual Heads of the National Churches, of both yours and ours, may take our places in cementing the Union between the Anglican and Orthodox Churches, which we have so humbly begun; then there will be no need of suggestions, such as I have made, as to how, or by whom, Services shall be performed; and, instead of praying that we “all may be one” we shall know that we are one in Christ’s Love and Faith.

Raphael, Bishop of Brooklyn.

Not long after issuing this letter, St. Raphael did an about-face, withdrawing from the Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union altogether, and instructing his people to disregard his previous letter. We’ll discuss those events in the near future.

Comments

2 responses to “St. Raphael and the Episcopalians in 1910”

[…] St. Raphael and the Episcopalians in 1910 […]

[…] Last week, we discussed St. Raphael’s involvement with the Episcopal Church — his role in an Orthodox-Anglican dialogue group, and his June 1910 letter permitting Episcopalian clergy to minister to Syrian Orthodox people in limited circumstances. Later that year, one of St. Raphael’s top assistants, Fr. Ingram Nathaniel Irvine, wrote a lengthy open letter, warning the Orthodox bishops in America of the Episcopalian threats to Orthodoxy. “Permit me to remind you, Fathers, that already the decks of the Protestant Episcopal battleships are cleared for action,” Irvine wrote. “Her Diocesan regiments, well equipped and united, are in ecclesiastical array.” He continued: […]