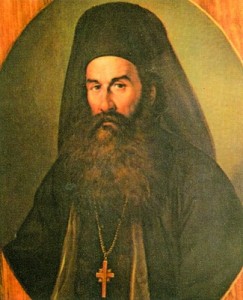

Today is both the Feast of the Annunciation (on the New Calendar), and Greek Independence Day. With that in mind, I decided to look in my archives for American accounts of the Greek War of Independence, in 1821. I have quite a few reports from various newspapers and journals, and the single event that received the most attention seems to have been the martyrdom of Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople. This took place at the very outset of the Greek Revolution, and was a direct Turkish response to the initial rebellion.

Patriarch Gregory was murdered on Pascha, in April, but the news didn’t start to trickle into the United States until the summer. Here’s the first report I’ve found, from the Connecticut Gazette (7/11/1821): “Constantinople is a scene of disturbance and massacre. The grand Seignor, to revenge the insurrection in his northern provinces, has had recourse to the most dreadful reprisals. The Greek Patriarch has been strangled, and four Archbishops have been massacred.”

The Religious Intelligencer (8/4/1821) soon published a fuller report. This account was sent from Vienna on May 17, and later appered in several other American periodicals.

Letters from Constantinople of the 25th April, give a deplorable picture of the state of things there. On Easter Sunday, April 23rd, when Gregory, the patriarch of Constantinople, 74 years of age, was just going to read High Mass in the Patriarchal Chapel, he was seized by order of the Sultan, and hanged at the door of the temple; a mode of death which in the eyes of all the Greeks is the most infamous, and must therefore excite boundless hatred. All the Archbishops and Bishops who were in the Church on account of the celebration of Easter, were either executed or thrown into prison. The congregation fled out of the Church to the neighbouring houses of the priest, but many were murdered by the enraged populace.

The cruel fate of the Patriarch appears to be the less merited, as he had, only on the 21st of March, solemnly proclaimed in the Chapel, curse and the ban of the Church against all the Greeks who attempted to withdraw from the Turkish yoke. In the formal anathema published on this occasion, he had (probably by compulsion) made use of the Holy Gospel to impress upon the Greeks that their Turkish Governors were appointed by God.

Nothing particular was proved respecting the motives for the execution of the Patriarch. But as Bishop Nicholas, of Trepoliza, in the Mora, leader of the Greeks and Mainotes, there in arms against the Turks, is brother to the murdered Patriarch, it is supposed that the Port[e] was thus induced to suspect the venerable old man. But it is certain that this execution will excite the utmost desperation among the Christians throughout Greece. It is worthy of remark, that all the Greek bishops who concurred in singing the anathema, now languish in prisons, and will probably share the fate of their Patriarch.

A note that follows the letter adds, “Several have since done so, and the Greek churches at Constantinople have been destroyed.” According to the official website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, “For three days, his [Gregory’s] body rested thus hanging, receiving the mockings of the angry crowd. A group of Jews bought the corpse and circulated it round the city, before throwing it in the Ceratius gulf. Fortunately, the captain Nicholas Sklavos, found his relic in the sea, and transfered it secretely to Odessa, where it was buried in the Greek Church of the Holy Trinity.” In 1871, Gregory’s relics were translated to Athens.

On October 5, the Christian Register printed a July 20 letter from Paris, offering some background on Patriarch Gregory:

Gregory, the pious and venerable Patriarch of Constantinople, who lately fell a victim to the infatuation and revenge of the populace, in the 80th year of his age, was a native of Peloponnesus. He was first consecrated to the Archepiscopal See of Smyrna, where he left honourable testimonials of his piety and Christian virtues. Translated to the Patriarchal throne of Constantinople, he occupied it at three distinct periods, for under the Musselman [Muslims] despotism was introduced and perpetuated, the anticanonical custom of frequently changing the head of the Greek clergy.

During his first Patriarchate he had the good fortune to save the Greek Christians from the fury of the Divan, who had it in contemplation to make the people responsible for the French expedition into Egypt. He succeeded in preserving his countrymen from the hatred of the Turks, but he was not the better treated for his interposition; the Turkish government banished him to Mount Athos. Recalled to his See some years after, he was again exposed to great danger in consequence of the war with Russia; and on the appearance of an English fleet off Constantinople, the Patriarch was exiled anew to Mount Athos, and once more ascended his throne, on which he terminated his career.

This Prelate invariably manifested the most rigid observance of his sacred duties; and in private life he was plain, affable, virtuous, and of an exemplary life. To him the merit is ascribed of establishing a patriarchate press. He has left a numerous collection of pastoral letters and sermons, which evince his piety and distinguished talents. He translated and printed in modern Greek, with annotations, the Epistles of the Apostles. He lived like a father, among his diocesans, and the sort of death he died adds greatly to their sorrow and veneration for his memory. This Prelate had not taken the least share in the insurrection of the Greeks; he had even pronounced an anathema against the authors of the rebellion; an anathema dictated indeed, by the Musselman’s sabres, but granted to prevent the effusion of blood, and the massacre of the Greek Christians.

The dates of these reports give a sense of the state of global communications in the early 19th century. Patriarch Gregory was killed in April, but news didn’t reach the US until July. The May 17 report from Vienna wasn’t published in America until August 4; the July 20 Paris letter made its first apperance on October 5. Another bit of news, dated September 12 and sent from St. Petersburg in Russia, was published in the Washington Gazette on December 4:

The Court Gazette of to day contains a long recital of the solemn interment of the Patriarch of Constantinople. It concludes with these words: — “It is in this manner that by order of Alexander I, Emperor of all the Russias, the last duties of Christian faith and charity, have been rendered to a holy Patriarch of the orthodox oriental Greek Church, Gregory, who suffered martyrdom.” This declaration formally denies the assertion of the [Turkish] Porte, in its answer to the Russian ultimatum, that the Patriarch was guilty of treason.

The American media — particularly the various Protestant journals — often held the Orthodox in rather low regard, viewing them as superstitious, backward idolators. I was somewhat surprised, then, to see Patriarch Gregory treated with such respect and admiration. I have not found a single American account of the Patriarch which was critical of him, or decried his role as a hierarch, or anything.

Patriarch Gregory had been hanged over the gate of the Phanar, the Patriarchal church. The gate was welded shut after Gregory’s death, and it remains sealed to this day, a memorial to the martyred Patriarch.

For more information, see the website of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, as well as the OrthodoxWiki entry for Patriarch Gregory. And if you read Russian (or use Google Translator), there’s an informative article on Gregory at this link.

3 responses to “The death of Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople, 1821”

[…] Review: The Russian Church and the Papacy – F.S. Lerner, Maccabee Society The Death of Patriarch Gregory V of Constantinople, 1821 – Matthew Namee, Orthodox Hstry Eritrean Christians Face A Time of Great Tribulation – […]

[…] http://45.77.159.119/2010/03/25/the-death-of-patriarch-gregory-v-of-constantinople-1821/ […]

[…] Greek priests, merchants, and officials were summarily executed around Constantinople; one report described of that day that “[a]ll the Archbishops and Bishops who were in the Church on account of the […]