Last week, I was privileged to speak at the Greek Archdiocese Clergy-Laity Congress in Atlanta. I gave the same talk on two days, July 5 and 6. Below, we’ve published the text of my lecture. A couple of things, up front: first, I didn’t include footnotes, because this was just the text I personally used in delivering the talk. And second, I make several references to Atlanta and Georgia, because that’s where I was speaking. Also, please forgive any typos or other errors; I know that there are a few, and I haven’t fixed all of them.

I’ve been asked to speak about Orthodoxy in the United States in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Of course, this was the Ellis Island era, the time when hundreds of thousands of people flocked to the United States from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. It’s when many of your ancestors came here; it’s also when my own ancestors came here, from what was then the Ottoman Empire and what is today Lebanon. Of course, besides the Greeks and the Syrians and Lebanese, there were also lots of Serbs, Romanians, Carpatho-Rusyns, and Bulgarians. These were largely Orthodox people, coming to the United States from all over the Orthodox world, and bringing with them their ancestral faith. And while these people spoke different languages and had different local traditions, they all shared that Orthodox faith. Because they came here and preserved their faith – because of that, we have Orthodoxy in America today. My goal here today is to give you a sense of what it was like back then – what it was like to be an Orthodox Christian in late 19th/early 20th century America.

In 1890, only two Orthodox parishes existed in the entire United States of America: a Russian cathedral in San Francisco and a semi-independent Greek church in New Orleans. Of course, there was a significant Russian Orthodox presence in Alaska, but at that time Alaska was just a territory, not a state, and it was both geographically and culturally disconnected from the US mainland.

The church in New Orleans was founded in 1865 by a group of Orthodox people led by a Greek cotton merchant named Nicolas Benachi. This was a multi-ethnic parish, and besides Greeks, it included Antiochians and Slavs among its members. The U.S. Census of 1890 describes it as a part of the Church of Greece, “in connection with the consulate of Greece in New Orleans.” The first priest to visit New Orleans – he wasn’t the parish priest, but he visited and served the first liturgy there – he was a strange character named Fr. Agapius Honcharenko. This man was an itinerant Ukrainian of questionable credentials who was visiting New York in 1865 when he was contacted by the New Orleans parish. He certainly was not connected to the Russian Church; he actually claimed that the Tsarist government had put a price on his head for his involvement in revolutionary activities. Honcharenko had some sort of connection with the Church of Greece, but not long after his visit to New Orleans, he left Orthodoxy altogether and tried to start his own Protestant sect in California.

The New Orleans parish itself was a really interesting community. Before they had actually organized themselves as a parish, they raised their own Orthodox militia regiment to fight on the Confederate side of the Civil War. Later on, from 1881 to 1901, the community had a priest from Bulgaria. Until 1906, most of the church records were kept in English. It was only later that Greek became the dominant language.

After I finished preparing this talk, I learned of some very exciting developments happening with the New Orleans parish. After Hurricane Katrina, the parishioners were cleaning out the church, and someone stumbled onto bunch of old documents, tucked away in some long-forgotten cupboard or closet. As it turns out, these were the sacramental records kept by the parish priests in New Orleans, dating back to the earliest years of the parish. The papers were soaking wet, and right now, the parish is having them restored. They show that the parish had members of all different ethnic groups, and in particular, a lot of Antiochians. And these people weren’t just concentrated in the city of New Orleans – they were in small towns all over Louisiana, and probably beyond. We’re just now beginning to get a glimpse of what life was like in the first Orthodox parish in the contiguous United States. There are plans to digitize the documents, and there’s even talk of building an Orthodox museum in New Orleans, to house the hundreds of documents and artifacts the community has accumulated over the past century and a half. Anyone interested in Orthodox history or Greek history will want to keep an eye on what’s going on in New Orleans.

The other really old parish, the San Francisco cathedral, was founded in 1868 under Russian authority. Just like New Orleans, San Francisco had a multi-ethnic Orthodox community. That community largely consisted of Greeks and Serbs, and in 1867, they formally requested that the Russian bishop in Alaska send them a priest. Soon after this, the Russian bishop moved his own residence down to San Francisco.

The San Francisco parish seemed almost cursed with turmoil. In 1879, the dean of the cathedral was apparently murdered, and one of the prime suspects was his assistant priest. A few years later, the Russian bishop drowned at sea; this appears to have been a suicide brought on by a physical ailment. In the late 1880s and early 1890s, the cathedral community was rocked by scandal. The new bishop, Vladimir, was accused of all kinds of horrific crimes. The cathedral itself burned to the ground, and many people suspected arson. Eventually, Bishop Vladimir was recalled to Russia, and by the end of the decade – by the end of the 1890s – the bishop in San Francisco was an outstanding man, Tikhon Bellavin, who was respected by all the different ethnic groups in the community. Bishop Tikhon went on to become Patriarch of Moscow. He suffered under the Communists, and in 1988, he was canonized a saint.

Now, as I mentioned, the New Orleans and San Francisco parishes were the only churches in the United States in 1890. They were outposts, really; there wasn’t much in the way of established Orthodoxy in America, outside of the Russians and Orthodox natives in Alaska. But after 1890, things began to change really rapidly. On the one hand, as I said before, thousands of Orthodox immigrants were arriving in the United States. And at the same time, entire parishes of Eastern Rite Catholics were converting, en masse, to Orthodoxy.

These Eastern Catholics were from the Austro-Hungarian Empires, and their ancestors had been Orthodox, but in the preceding centuries, they had left the Orthodox Church and joined the Roman Catholics. When they came to the United States, they were not very well-received by the Roman Catholic hierarchy in America. The big moment came in 1889. An Eastern Catholic priest named Alexis Toth had just arrived in Minneapolis, Minnesota, to take over pastoral care of the Eastern Catholics in the area. And as was the standard procedure, when he got to Minneapolis, he presented himself to the local Roman Catholic archbishop, a man named John Ireland.

Archbishop Ireland was absolutely livid that Toth had come to Minneapolis. Ireland shouted at Toth, “I have already written to Rome protesting against this kind of priest being sent to me.” Toth said, “What kind of priest do you mean?” And Ireland said, “Your kind.” And then he continued, “I do not consider either you or this bishop of yours Catholic. […] I shall grant you no permission to work there.” Later on, Toth said, “The Archbishop lost his temper, I lost mine just as much.”

Unwelcomed by the Roman Catholics, Toth began to look into other options. At this point – and here, we’re talking right around 1890 – there wasn’t much in the way of Orthodoxy in America, as we’ve seen. Toth eventually contacted the Russian bishop in San Francisco, and his entire Eastern Catholic parish in Minneapolis converted to Orthodoxy. Toth himself became a leading proponent of Eastern Catholic conversions to Orthodoxy. Tens of thousands of Eastern Catholics joined the Russian Orthodox Church in America over the next several decades. The core of the growing Russian Archdiocese – and the core of what we know today as the OCA – consisted of these former Eastern Catholic parishes. The significance of the Eastern Catholic conversions cannot be overstated – this was a major, major development.

Of course, at the same time that this was happening – literally, at exactly the same time – thousands of people who were already Orthodox were coming to the United States from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean. And these people were also starting their own Orthodox churches.

One of the most interesting of these early communities was in Chicago. In the 1880s – so, even before the big immigration started – Chicago had a growing Orthodox population. By 1888, there were about a thousand Orthodox in the city. Most of them were Greeks and Serbs, and despite the fact that they weren’t Russian, they petitioned the nearest bishop – who was Russian – to send them a priest. In 1888, the Russian bishop responded to their petition by asking them to hold a meeting, to figure out if there was enough interest to support a church. The main speakers at the meeting were a Greek, a Montenegrin, and a Serb. The Greek man was George Brown, who had come to America as a young man, and had fought in the American Civil War. George Brown gave a short speech, and it’s short enough that I’ll read most of it to you now, exactly as the Chicago Tribune reported it the next day:

“Gentlemans,” he said, “Union is the strength. Let everybody make his mind and have no jealousy. I have no jealousy. I am married to a Catholic woman but I hold my own. Let us stick like brothers. If our language is two, our religion is one. The priest he make the performance in both language. We have our flags built. It is the first Greek flags raised in Chicago. We will surprise the Americans. Let us stick like brothers.”

The meeting ended with everybody wanting to start an Orthodox church, and they agreed that the services could be done in both Greek and Slavonic. The Russian Bishop Vladimir traveled east from San Francisco for a visit later that year, but unfortunately, this was the same Bishop Vladimir who became embroiled in a series of horrible scandals. One of Vladimir’s strongest opponents in San Francisco was a Montenegrin who happened to be the brother of one of the leaders of the Chicago community. So the Chicago Orthodox were hearing all these horrible things about Bishop Vladimir, and they decided they wanted nothing more to do with the man. They put out feelers to numerous other Orthodox churches – the Serbian Church, the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and the Church of Greece.

Eventually, the Church of Greece sent a priest named Fr. Panagiotis Phiambolis, and in 1892 Phiambolis established the first Orthodox parish of any kind in Chicago. But this was not a multi-ethnic parish, like San Francisco and New Orleans. This parish was specifically for Greek people. The Chicago Tribune reported that the new Greek church “wants no one but those of Hellenic blood among its members” Almost exactly one month after the Greek church began in Chicago, the Russians established their own church. By now, I should note, Bishop Vladimir had been recalled to Russia, and was replaced by Bishop Nicholas.

So now in 1892, there were two Orthodox parishes in the city of Chicago – one Greek, one Russian. This was the first time in our history that two Orthodox churches, answering to different ecclesiastical authorities, coexisted in the same US city. But there’s a flip side to all of this. Despite the fact that they had separated based on language and ethnicity, they still got along with each other. In 1894, the Chicago Greek and Russian priests concelebrated the Divine Liturgy at the Russian church to commemorate the one hundredth anniversary of the Russian mission to Alaska. When the Russian Tsar Alexander III died the following month, a memorial was served by both the Greek and Russian priests at the Greek church, which was simultaneously dedicating its new building. When the new Russian bishop, Nicholas, visited Chicago in later that year, the local Greek priest, Phiambolis, participated in the hierarchical Liturgy at the Russian church. Later on, in 1902, the church bell was stolen from the Russian parish, and the Greek priest invited his Russian counterpart to come to the Greek church and ask the Greek parishioners for help. The two churches, Greek and Russian, then held a joint meeting of both parishes, to organize an effort to find the bell.

On the Pacific Coast, Orthodox communities began to organize themselves in places like Portland, Oregon, and Seattle, Washington. In both Portland and Seattle, there was a lot of diversity among the Orthodox, with Greeks, Serbs, Antiochians, and Russians all in the same community. And in both Portland and Seattle, these diverse Orthodox populations affiliated themselves with the Russian Church. Seattle is a really interesting story, because, while it was under the Russian Church, the parish itself was named after St. Spyridon, who of course is a Greek saint. How did that happen? Well, the land for the church was donated by a Greek family, and because of that, they got to choose the name. Church services were in Greek, Slavonic, and English, and one of the prerequisites for being the pastor in Seattle was an ability to work in multiple languages.

Seattle’s multi-ethnic community didn’t last forever. By 1917, there were over two thousand Greeks in Seattle, and they decided they needed their own Greek church. But there weren’t any hard feelings. People said that they were just happy that there were enough Orthodox in Seattle for two churches.

Fr. Michael Andreades was of the early priests of that original multi-ethnic Seattle parish. Andreades was Greek, but he had been educated in Russia, and he was under the Russian bishop in San Francisco. He was one of several ethnic Greek priests who served under the Russian diocese. This was certainly not the norm for Greek clergy in America, but it definitely was not unheard of.

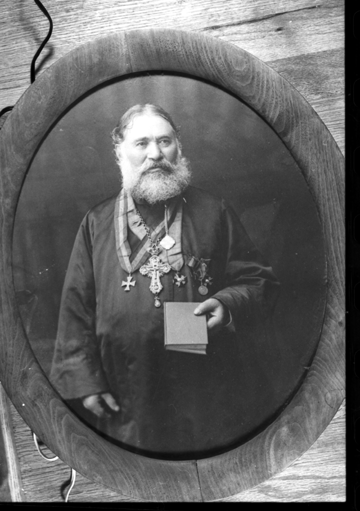

Another of these Greek priests was Fr. Theoclitos Triantafilides. His father was an Athenian who fought in the Greek War for Independence, and then afterwards moved to the Peloponnese. That’s where Triantafilides himself was born. As a young man, Triantafilides went to Mount Athos and was tonsured a monk. He became affiliated with the Russian monastery of St. Panteleimon, on Mount Athos, and from there, he went to Russia itself, where he studied at the Moscow Theological Academy. This is where things get really interesting. Triantafilides was asked by King George I of Greece to come to Greece and tutor the king’s young son, Prince George. Then the Russian Tsar, Alexander III, asked Triantafilides to return to Russia and tutor his children, including the future Tsar Nicholas II. Triantafilides was actually one of the priests who served at the wedding of Nicholas II and his wife Alexandra.

So how did Triantafilides go from the royal courts of Greece and Russia to the United States? Well, in Galveston, Texas – which was a major seaport in the 19th century – there was another one of those multi-ethnic Orthodox communities. The Greeks and Serbs of Galveston got together and petitioned the Russian Church to send them a priest. Tsar Nicholas II himself answered their petition by sending them his old tutor, Triantafilides, who by this time was in his early sixties.

Triantafilides was the priest in Galveston for over 20 years, until his death in 1916. But he didn’t just take care of the Galveston parish. He took responsibility for the Orthodox people living throughout the Gulf Coast, traveling thousands of miles by horse and by train. His parish, which was named Ss. Constantine and Helen, eventually came to be predominantly Serbian, and many years after his death, the church switched from the Russian to the Serbian jurisdiction. But to this day, they continue to venerate their original Greek priest, sent by the Russian Tsar.

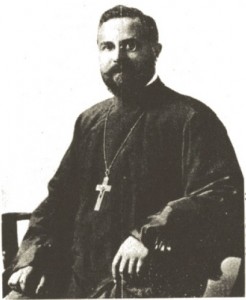

But Fr. Theoclitos Triantafilides was not the first prominent Greek priest in America. That title belongs to Fr. Kallinikos Kanellas, who arrived in San Francisco in the early 1890s. Kanellas came to the US from India, where he had been the priest of the Greek Orthodox church in Calcutta. He initially came to America just for a visit, but he was a sickly man, and he became ill, which forced him to stay for awhile. He became affiliated with the multiethnic Russian cathedral in San Francisco. Of course, with so many Greeks there, having a Greek priest would have been particularly helpful. Like so many of his fellow priests, Kanellas traveled all over the country. He actually seems to have been the first Orthodox priest to visit this state – Georgia – when he baptized a Greek child in Savannah in 1891.

In 1892, a new Russian bishop took over in San Francisco, and he released Kanellas, who then traveled to the eastern part of the United States. Around 1902 or 1903, Kanellas was asked to become the priest of the Greek church in Birmingham, Alabama, which was under the Church of Greece. He spent the next eight years there. The Greek-American Guide described him as “a very sympathetic and reverend old man.” He was one of the only Orthodox priests in the entire American South, so like Triantafilides, he traveled quite a bit. One of the places he visited was Atlanta. Kanellas eventually became the first priest of the Greek church in Little Rock, Arkansas, and he remained there until his death in 1921.

Priests like Andreades, Triantafilides, and Kanellas were not Russian, but they all spent time serving in the Russian diocese. The reverse didn’t happen – Russian priests didn’t serve under the Church of Greece. But there is a fascinating story that I must tell you – because not all of the Greek priests were, in fact, Greek.

Just after the turn of the twentieth century, a man named Robert Morgan began to attend the Greek church in Philadelphia. The curious thing about Robert Morgan is that he was a black Episcopalian deacon from Jamaica. In 1907, he traveled to Constantinople, and was ordained an Orthodox priest. He was sent back to Philadelphia, and I’ll quote directly here, “to carry the light of the Orthodox faith among his racial brothers.” Morgan took the name “Fr. Raphael,” but unfortunately, he wasn’t very successful in his missionary work. Aside from his own family, there’s no clear evidence that he converted anyone else to Orthodoxy. But the startling fact remains that at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Ecumenical Patriarchate initiated a mission to convert black Americans to Orthodoxy.

Now, as I said, Fr. Raphael Morgan was attached to the Greek church in Philadelphia. When he went to the Ecumenical Patriarchate to be ordained, he had two letters in his possession. One was from the Greek community of Philadelphia, which supported Morgan’s ordination, and said that if he failed to establish a black Orthodox church, he was welcome to be the assistant priest at their parish. The other letter was from the parish priest in Philadelphia, a remarkable man named Fr. Demetrios Petrides.

Petrides was born on Samos in the mid-1860s. He was a married priest, with children, but his wife died before he came to America. Back in Greece, Petrides’ daughter fell in love with a young man, John Janoulis, and they wanted to get married. Petrides approved, but the Janoulis’ father wanted his son to get an education, rather than get married. So Janoulis was disowned by his father, and Petrides took the couple under his wing. The young Janoulis left for America to earn money, which of course was common practice at the time, and then Fr. Demetrios was asked by the Church of Greece to become the new priest in Philadelphia. He arrived in 1907, and brought along his daughter, reuniting her with her husband. Just a couple of months after he arrived in America, Petrides wrote his letter, recommending that Robert Morgan be ordained a priest. For a while, Morgan actually lived in the Petrides family home.

Like so many of his fellow priests, Petrides traveled throughout his region of the country, ministering to the Orthodox people he found who didn’t have a priest. One time, he went to Ithaca, New York, to do a baptism. After the service, unbeknownst to Petrides, a 16-year-old Greek girl had advertised that she would go into a “spirit trance.” Greeks had traveled from all over to witness the spectacle. Petrides caught wind of what was going on, and he burst into the room, stopped the girl’s trance, and told the people that spiritualism is against the teachings of the Orthodox Church. This was the sort of man he was – completely unafraid to stand up for what was right, no matter what.

It was this gumption that got Petrides run out of Philadelphia. The Philadelphia church was dominated by a rich layman, Constantine Stephano, who was a millionaire cigarette manufacturer. Stephano and Petrides did not get along. Things came to a head in 1912, when Stephano sent the following message to Petrides – this is almost unbelievable. It said,

“Constantine Stephano commands you to appear at his office every evening at sunset and salaam low upon entering his presence. Then you are to stand erect, with folded arms, with your eyes cast downward, awaiting a word from Stephano before sitting down or otherwise changing your position. If you are not asked to be seated you are to remain in this position until Stephano leaves his office, and when he passes through the door you are to salaam low again and depart with bowed head.”

Stephano was obviously trying to humiliate Petrides, and Petrides would have none of it. He responded, “I will not thus humiliate myself before this maker of cigarettes.” Now, in the early twentieth century, Greek parishes in America had only a loose connection to the church authorities in Athens or Constantinople. As a practical matter, the parishes were run by lay boards of trustees, which would hire and fire priests at will. Constantine Stephano arranged for Petrides to be ousted from the Philadelphia church, by the slim margin of seven votes.

But, characteristically, Petrides left with his head held high. In September of 1912, newspapers in Georgia began reporting that a daring Greek priest was coming to Atlanta. One newspaper called Petrides “the stormy petrel of the cloth.” Another paper said that he was famous for his “lambasting of the rich Greeks who loved money for the sake of power.” He was warmly welcomed by the Greeks in Atlanta, who seemed to have a good idea of the sort of priest they were getting.

But Petrides was not simply focused on his fellow Greeks. At the turn of the twentieth century, there was a very active dialogue taking place between the Orthodox and the Episcopalians. This led to the creation of a group called the “Anglican and Eastern Orthodox Churches Union.” The Orthodox members of the group included clergy from various ethnic backgrounds, including Antiochians, Russians, and Greeks. For several years in the teens, Fr. Demetrios Petrides was the organization’s Greek representative. He thus was engaged in this national inter-Christian dialogue, and he was also cooperating with his fellow Orthodox of different ethnicities.

As the teens wore on, Petrides developed diabetes, and in the days before insulin, that was a death sentence. He died in September of 1917. Annunciation Cathedral here in Atlanta should be very proud to claim Fr. Demetrios Petrides as one of its first priests. He was a significant historical figure, and an outstanding pastor.

We’re nearly at the end of this talk, and I’ve basically just told you a series of stories. So what’s the point – are there any common threads, or lessons to be learned, from this admittedly limited look at early Greek Orthodox history in America? I think there are, and I’ll just touch on them very briefly here at the end.

First and foremost, it should be clear that Greek Orthodoxy in America did not develop in a vacuum, somehow separated from the rest of Orthodoxy in America. Most of the earliest communities of Orthodox Christians here were multi-ethnic. This was largely a matter of practicality: there simply weren’t enough people in each individual group to start forming separate ethnic parishes. In many places – San Francisco, New Orleans, Chicago, Seattle, Galveston – there was a clear sense that, for Orthodox Christians to survive in America, they needed each other. They needed – we still need – to work together to build up Orthodoxy in our local communities. No matter what we’d like to think, we’re simply too small, too weak, to thrive on our own, without each other. And just as in those early parishes, cooperation and a unified effort does not imply the abolishment of our individual identities. I will always be Lebanese, just as so many of you will always be Greek. Working together, on a practical level, does not have to mean a compromise of our heritage. It didn’t a hundred years ago, and it does not now.

I’d like to close with the words of that Greek veteran of the Civil War, George Brown, the early leader of Chicago’s Orthodox community: “Union is the strength. Let everybody make his mind and have no jealousy. Our religion is one. We will surprise the Americans. Let us stick like brothers.” Thank you.

[This article was written by Matthew Namee.]

Comments

9 responses to “The Historical Reality of Greek Orthodoxy in America”

Any blow-back resulting from the revelation in the Q&A that New Smyrna, FL was not settled by Orthodox Greeks but by Greek Catholics with a Catholic priest in tow?

After my talk, I spoke with the person who runs the St. Photios Shrine in St. Augustine, Florida. She (very graciously, I might add) explained to me that the Greeks who came to New Smyrna were almost all Orthodox, and that the original plan was for an Orthodox priest to accompany them. She gave me a copy of the definitive book on the New Smyrna colony, which showed evidence of this. She also said that the Orthodox remained Orthodox and prayed separately from the Roman Catholics. I wasn’t able to find evidence of this in the book, but it’s possible.

At the same time, she acknowledged that the descendants of the New Smyrna Greeks left the Orthodox faith, and that the New Smyrna colony is not significant vis-a-vis the history of Orthodoxy in America. I hope that this lady, the head of the St. Photios Shrine, will contribute an article on New Smyrna for our website.

By the way, Orrologion, where did you see/hear my talk? Is the video/audio available now, or were you in Atlanta?

Bp Savas of Troas mentioned that it came up in the Q&A, but he did not know about your conversation with the head of the St. Photios Shrine, of course.

What evidence did the book on New Smyrna provide that evidenced the colonists were Orthodox? How does this relate to the evidence that led you to believe they were not Orthodox? Did the book she provide show early, primary evidence or was it simply a matter of later stipulation or assumption?

I hope she provides an article on New Smyrna, too. Culturally, it is definitely important to the Greek-American community, the question is whether or not there are religious implications, as well – which the establishment of a Shrine would imply. Even if there were Orthodox, it is nice to hear she acknowledged it would be essentially a barren shoot whose history is “not significant vis-a-vis the history of Orthodoxy in America” – much like the interesting but otherwise irrelevant (“vis-a-vis the history of Orthodoxy in America”) info regarding the Orthodoxy of Col. Philip Ludwell III in Colonial Virginia.

The book is by E. Panagopoulos. I checked it again after reading your comment, and it actually is not 100 percent clear that the Greeks were Orthodox. It does refer to “Greek priests” and the “Greek Church,” but it doesn’t explicitly say anything about the Orthodox Church, or the Ecumencial Patriarchate, or anything like that. The head of the St. Photios Shrine was quite confident that these Greeks were indeed Orthodox, but from Panagopoulos’ book, I don’t think I can say that with total confidence.

Papagopoulos does rely on primary sources. Part of the problem is that these tend to be English-language sources (at least, the sources I checked), and thus weren’t written by people who were very familiar with Orthodoxy.

I agree that, at best, New Smyrna is basically analagous to the Ludwell story. However, Nicholas Chapman has uncovered some evidence which hints at a POSSIBLE connection between Ludwell’s son-in-law, John Paradise, and the initiation of the Kodiak Mission that reached Alaska in 1794. So, there may be slightly more to the Ludwell story than meets the eye. We’ll see what Nicholas can turn up.

Incidentally, when I get time, I plan to go through Panagopoulos’ book and make a list of all the possible references to the Orthodox Church, and then present them here at OH.org.

“After my talk, I spoke with the person who runs the St. Photios Shrine in St. Augustine, Florida. She (very graciously, I might add) explained to me that the Greeks who came to New Smyrna were almost all Orthodox, and that the original plan was for an Orthodox priest to accompany them. She gave me a copy of the definitive book on the New Smyrna colony, which showed evidence of this. She also said that the Orthodox remained Orthodox and prayed separately from the Roman Catholics. I wasn’t able to find evidence of this in the book, but it’s possible.”

What book is that?

There was a plan for a Greek priest when it was on the drawing board: the grant was to populate the colony with Protestants, but the Anglicans had already made links to the Orthodox in Russia and visiting Greeks (one Greek bishop, it is said, being the source of Methodist orders). The Orthodox Russians were also known at the time to be undermining Spain’s claim on the Pacific, as the English hoped to do in Florida. So an Orthodox priest posed no problem for the Estalished Church in London. It seems, however, that Turnbull wife, Greek but in communion with the Vatican, used that exemption to get a priest of her choosing.

As for the authorities in Old Smyrna, Turnbull was barred from recruiting, and it remains doubtful that a priest would have gotten canonical release.

I’ve posted the Episcopalian claim that the Greeks went to them to during English rule, something I haven’t seen substantiated by the contemporary sources I’ve seen, but can’t discount out of hand.

http://45.77.159.119/2009/12/greeks-in-florida-1768/#comment-1059

It’s New Smyrna: An Eighteenth Century Greek Odyssey, by E.P. Panagopoulos. You can find it on Amazon here:

http://www.amazon.com/New-Smyrna-Eighteenth-Century-Odyssey/dp/0916586146

[Panagopoulos’ book] does refer to “Greek priests” and the “Greek Church,” but it doesn’t explicitly say anything about the Orthodox Church, or the Ecumencial Patriarchate, or anything like that. The head of the St. Photios Shrine was quite confident that these Greeks were indeed Orthodox, but…

I guess the real question is what Panagopoulos’ claims are made on. Especially in 1966, when the book was written, a claim for “we were here first, so we get the continent” was highly sought after. It is also not rare for Greeks to simply assume all Greeks are Orthodox. Was Panagopoulos simply assuming the Greeks were Orthodox or are these references to “Greek priests” and the “Greek Church” simply assumed by the fact the New Smyrnaens were Greek and had a priest with them?

Your past arguments as to their likely not being Orthodox seem to make more of an argument based on facts.

Can I reprint the photo of the old Holy Trinity church in GreekCircle magazine? To whom do I attribute the photo?