Editor’s note: Last week, we presented the first part of the first biography of St. Innocent, written by the Episcopalian clergyman Charles R. Hale. What follows is Part 2, which details the introduction of Orthodoxy to Alaska and the priestly ministry of Fr. John Veniaminoff, the future St. Innocent. Tomorrow, we will publish the last section of Hale’s article, which focuses on St. Innocent’s tenure as a bishop.

“Who in the West,” asks Mouravieff, “hears anything of the truly apostolical labors of the Archbishop of Kamchatka, who is ever sailing over the ocean, or driving in reindeer sledges over his vast but thinly settled diocese, thousands of miles in extent, everywhere baptizing the natives, for whom he has introduced the use of letters, and translated the Gospel into the tongue of the Aleoutines?” Few, indeed, have heard, doubtless there are many who would be glad to hear.

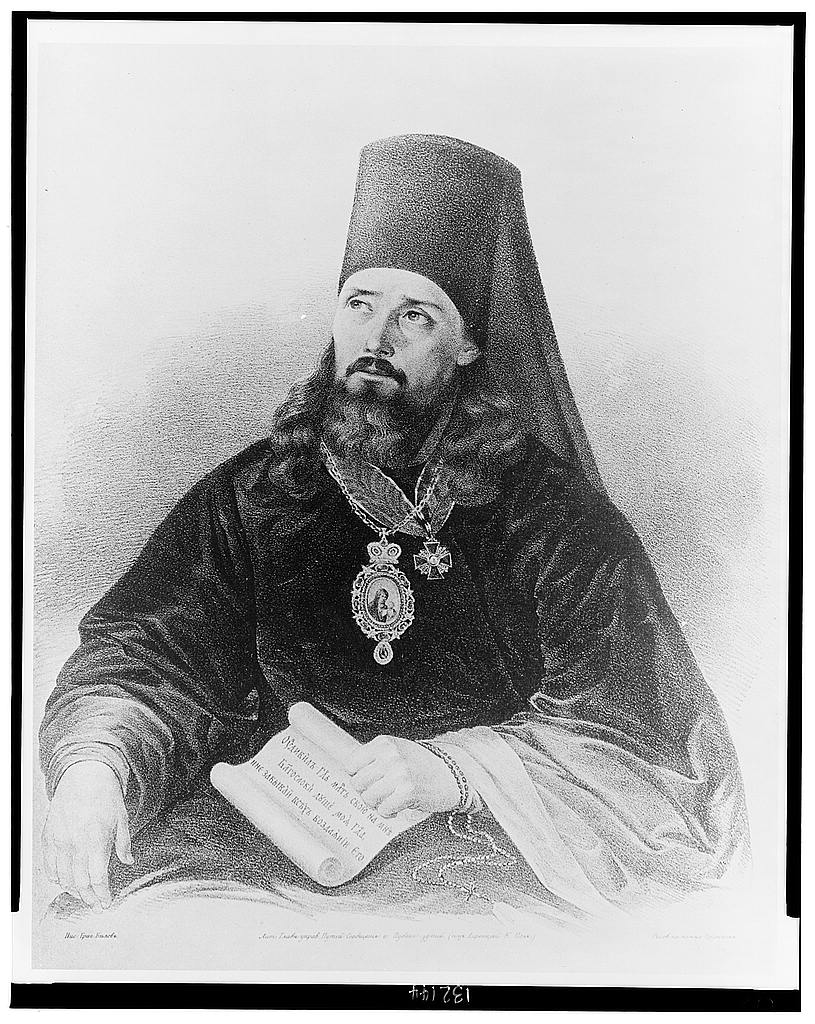

The present Metropolitan of Moscow, late Archbishop of Kamchatka, has been called “the Russian Selwyn,” but he began his missionary labors much earlier than the late [Anglican] Bishop of New Zealand, and has been called to a yet higher position of dignity and influence in his own Church, than that held by the Bishop of Lichfield. John Veniaminoff was born August 20 (September 1, o.s.), 1797, was educated in the Seminary of Irkutsk, from which he graduated in 1817, and entered upon the sacred ministry in May of that year. He was advanced to the priesthood in 1821. December 15 (27 o.s.), 1840, Innocent, for by this name he is henceforth known, was consecrated, by the Episcopal members of the Holy Synod, in the Kazan’s Cathedral at St. Petersburg, to the newly founded Bishopric of Kamchatka. In 1850, his See was made Archi-episcopal. Early in 1868 he succeeded the honored Philaret as the Metropolitan of Moscow. It is a curious coincidence that Bishop Selwyn was consecrated but a few months later than he, October 17, 1841; and the appointment of Innocent to Moscow was announced within a very few days of the time when the Bishop of Lichfield entered upon his new charge, January, 1868.

Of the first two years after his ordination to the priesthood, in which he seemed to have been engaged in parish work in the Diocese of Irkutsk, we have no record. But in 1823 he offered himself as a missionary and was sent by his Bishop to Ounalashka [Unalaska]. Let us preface the story of his labors there, as he himself does, by a brief account of earlier work in the same region. In doing this we translate from his own words, for lack of space however greatly abreviating [sic] his narrative.

How attractive his exordium:

Knowing how pleasant it is for the true Christian to hear of the propagation of Christianity among nations previously unenlightened by the Holy Gospel, I have determined to set forth what I know concerning the propagation and establishment of Christian truth in one of the most remote parts of our country, where, by the will of God, I have been led to spend many years.

Then he goes on to show how

The Christian religion crossed to the shores of Russian America with the first Russians who went to establish themselves in those parts. Among those who sought at once to establish a new industry for Russia, and to acquire gain for themselves, there were those who resolved, at the same time, upon the establishment of Christianity amongst the savages with whom they dwelt. The Cossack, Andrean Tolstich, about 1743 discovering the island known under the name Andreanoffsky, was probably the first to baptize the natives. In the year 1759, Ivan Glotoff discovering the island of Lisa, baptized the son of one of the hereditary chiefs of the Lisevian Aleoutines. He afterwards took the young man to Kamchatka, where this first fruits of the Ounalashka Church spent several years and studied the Russian language and literature and then, returning to his native country, with the position of chief Toen (Governor) conferred upon him by the Governor of Kamchatka, helped greatly by his example, in the propagation of Christianity.

The good missionary confesses that self-interest had something to do with the desire, on the part of many of the first settlers, for the spread of Christianity among the savages, they thinking that thus they would be able to establish better relations with the natives. When we think of the way in which Americans and English have too often acted toward the savage tribes with whom they have been brought into contact, instead of blaming the defective motive, on the part of some, we may rejoice that, in this instance: “The desire of Russians for gain served as a means for diffusing the first principles of Christianity among the Aleoutines, and aided the labors of the missionaries who came after.”

Mr. Shelikoff, founder of the American company:

Among his many plans and projects for the advancement of the interests of the American part of our territory, had in view especially the propagation of Christianity, and the founding of Churches. On which account, on his return from Kadiak [sic] in the year 1787, he laid a memorial in regard to this before the Government and begged it to found an Orthodox Mission, of which he and his associate Golikoff took upon them the expense both of establishment and sustaining. As a result of his intercessions there was founded at St. Petersburg a mission of eight monks, under the lead of Archimandrite Joseph, for the preaching of the word of God among people brought under Russian dominion. Well provided for by Shelikoff, Golikoff, and other benefactors, the mission set out from St. Petersburg in the year 1792, and in the following autumn arrived at Kadiak.

At once they entered upon their work, beginning on the Island of Kadiak. In 1795, Macarius went to the Ounalashka district on a missionary tour, and Juvenal visited the Tehougatches, and crossed over the Gulf of Kenae, both being everywhere warmly received by the natives. The year after, Juvenal, in the neighborhood of the lake of Pliamna, or Shelikoff, “finished his apostolic labors with his life, serving the Church better than any of his associates.” Many years afterward, the circumstance[s] of his martyrdom were related by the natives. Some other members of the mission gave special attention to the education of the children, one of them, Father German [Herman], founded an Orphan Asylum, of which he remained in charge until his death in 1837.

Shelikoff realized the importance of having the work properly organized, and so he was not content with such a mission as was sent out. “He urged the founding of a Bishopric in Russian America, under the charge of its own bishop. He fixed upon Kadiak as a the proper residence of a bishop, estimating the population of that island as about fifty thousand. In consequence of his entreaties, and in consideration of the number of inhabitants,” an Episcopal See was founded, and Joseph, Archimandrite of the mission, was summoned to Irkutsk, and there consecrated, in March 1799, by the Bishop of Irkutsk, and there consecrated, in March 1799, by the Bishop of Irkutsk, to be the first Bishop of “Kadiak, Kamchatka and America.” The new Bishop, as he returned homeward, was lost at sea, in the ship Phoenix, with all who accompanied him, including the priest Macarius and the deacon Stephen, who had come with him from St. Petersburg, when the mission was founded.

Soon after this Shelikoff died, and all thought of extending the mission, and of setting up a Bishopric, seemed lost sight of for years. In the whole colony there was but one missionary priest, until in 1816, in response to the entreaties of Baranoff the Governor, Michael Sokoloff was sent to Sitka.

A fact in this connection, not generally known, may here be mentioned that a Russian settlement, under the name of Russ, was made, under the auspices of Baranoff, in California, on the coast about forty miles northwest of San Francisco. A number of Indians here became members of the Orthodox Church, and when the colony was removed to Sitka, went northward with it. Of these Indian converts or their descendants there were in 1838 nine still living at Sitka. In 1821 new privileges were granted to and new regulations made for the Russian American Company, and the duty was laid upon it of maintaining a sufficient number of priests for the colony. Accordingly three were obtained from Irkutsk, in 1823 John Veniaminoff for Ounalashka, in 1824 Frumentius Mordovsky for Kadiak and in 1825 Jacob Netchvatoff for Atcha.

Veniaminoff entered upon his work with enthusiasm and a hearty liking for those among whom he was to labor. He recounts how Father Macarius and others who had preached the Gospel amongst them

did not present to them with fire and sword the new faith, which forbade them things in which they delighted — e.g., drunkenness and polygamy, but notwithstanding this the Aleoutines received it readily and quickly. Father Juvenal remained in the Ounalashka district but one year, and voyaging to distant islands, and travelling from place to place with only one Russian attendant, the Aleoutines whom he had baptized, or whom he was preparing for Holy Baptism, conveyed him from place to place, sustained him and guarded him without any recompense or payment. Such examples are rare.

Although the Aleoutines willingly embraced the Christian religion, and prayed to God as they were taught, it must be confessed that, until a priest was settled amongst them, they worshipped one who was almost an unknown God. For Father Macarius, from the shortness of time that he was with them, and from the lack of competent interpreters, was able to give them but very general ideas about religion, such as of God’s omnipotence, His goodness, etc. Notwithstanding all of which, the Aleoutines remained Christian, and after baptism completely renounced Shamanism, and not only destroyed all the masks which they had used in their heathen worship but also allowed the songs which might in any way remind them of their former belief to fall into oblivion. So that when, on my arrival amongst them, I through curiosity made enquiry after these songs, I could not hear of one. And as to superstitions, from which few men well taught in Gospel truth are quite free, many which they had they quite gave up, and others lost their power over them. But of all the good qualities of the Aleoutines, nothing so pleased and elighted my heart as their desire, or, to speak more justly, their thirst, for the word of God, so that sooner would and indefatigable missionary tire in preaching than they in hearing the word.”

But Veniaminoff’s missionary service was not with the peaceful Aleoutines only. There was a fierce tribe, the Koloshes, who, to use his words, when first met with, in 1804, “like fierce wild beasts hunted the Russians to tear them in pieces, so that these had to shut themselves up in their fortresses or go out in companies.” And even in 1819 they still looked “on Russians as their enemies, and slew such as they could take by night, in revenge for the death of their ancestors slain in contests with them.”

To these he resolved to carry the Gospel. To this end he came to Sitka, in the neighborhood of which the Koloshes lived, towards the close of 1834. That Winter and the ensuing Spring imperative duties detained him among the Aleoutines at Sitka. When Summer came, he found that the Koloshes had left their settlements and were scattered in different parts for the purpose of fishing. Veniaminoff confesses, too, that he had a shrinking from meeting these hostile savages. Ashamed of himself for what he felt to be cowardice he resolved that immediately upon the close of the Christmas holidays he would take his life in his hand and go.

“Let no one wonder,” he goes on to say, “at the decrees of Providence.”

Four days before I came to the Koloshes the small-pox suddenly broke out amongst them and first of all at the very place where I had expected to make my first visit. Had I begun my instruction of the Koloshes before the appearance of the small-pox they would certainly have blamed me for all the evil which came upon them, as if I were a Russian shaman or sorcerer who sent such a plague amongst them. The results of such inopportune arrival would have been dreadful. The hatred towards the Russians, which was beginning to wane, would have become as strong as ever. They would perhaps have killed me, as the supposed author of their woes. But this would have been as nothing in comparison with the fact that my coming to the Koloshes just before the small-pox would probably have caused the way to be stopped for half a century to missionaries of God’s word, who would always have seemed to them harbingers of disaster and death.

But, Glory be to God who orders all things for good! The Koloshes were not now what they were two years previously (when he had meant to come among them). If they did not immediately become Christians they, at least, listened or began to listen to the words of salvation. Few were baptized then, for, while I proclaimed the truth to them, I never urged upon them or wished to urge upon them the immediate reception of Holy Baptism, but, seeking to convince their judgment, I awaited a request from them. Those who expressed a desire to be baptized I received with full satisfaction. I always obtained from the Toens (or chiefs) and from the mothers of those desiring to be baptized a consent which was never denied, and this greatly pleased them.”

Veniaminoff introduced inoculation amongst the Koloshes, and the good they saw ensuing from this “greatly changed their opinion of the Russians and of their shamans (or magicians). They neither forbade nor did anything to hinder the reception of Holy Baptism by those desiring it. Instead of despising or avoiding those baptized they looked on them as persons wiser than themselves and almost Europeans.”

After sixteen years of missionary toil Veniaminoff was sent to St. Petersburg to plead for help for the mission. The Czar Nicholas proposed to the Holy Synod to send one who had proved so faithful a priest back to the scene of his labors as a Bishop, for Episcopal supervision was manifestly greatly needed. “Your Majesty must consider,” suggested some members of the Synod, “that, though he is no doubt an excellent man, he has no Cathedral, no body of clergy and no Episcopal Residence.” “The more then, like an Apostle,” replied the Czar, “Cannot he be consecrated?” The objections of those prelates remind us of some that have more recently been heard nearer home. It is to be hoped that, where the need of a Bishop is evident, such objections may soon be things of the past.

As has been already stated the good missionary priest was, December 15 (27 o.s.), 1840, consecrated in St. Petersburg to be Bishop of Kamchatka, with the name, by which he will hereafter be known, of Innocent.