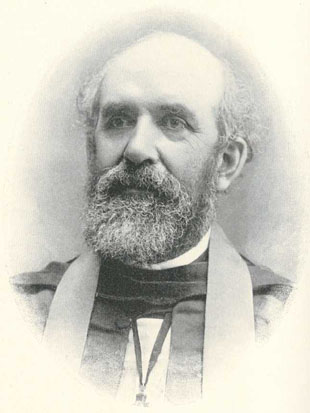

Editor’s note: The first biography of St. Innocent of Alaska was not written by an Orthodox author, but by an Episcopalian, Charles R. Hale, in 1877 (a year before St. Innocent’s death). Hale (1837-1900) was an Episcopal priest (and later a bishop) who had great affection for the Orthodox Church. For a good summary of Hale’s life and his connection to Orthodoxy, click here.

Today, we’re presenting the first part of Hale’s biography of St. Innocent. Next week, we’ll publish Part 2, and in the future, we’ll offer more of Hale’s writings on Orthodoxy. This biography originally appeared in the journal American Church Review (July 1877).

It has long been the habit of persons unfriendly to the Orthodox Churches of the East to speak of them as well night dead Churches. The charge has been but too eagerly repeated by such as, determined upon a certain course of public policy, through a blind selfishness which must surely bring, if persisted in, a dread Nemesis, were not inclined to think well of Eastern Christians, whom it would have been inconvenient to recognize as brethren. A favorite specification in the accusation brought against Christians of the East has been, that they were utterly wanting in a missionary spirit. In these days, we know something of what enslavement to the Turk involves. And what, in common justice, to say nothing of Christian charity, have we a right to expect from those groaning under such bondage? Does not Mouravieff’ well demand, as to these, in Question Religieuse d’Orient et d’Occident,

Have we the conscience to ask that they should make converts, when, now for more than four hundred years, they have been struggling, as in a bloody sweat, to keep Christianity alive under Moslem tyranny? And, in that time, how many martyrs, of every age and condition, have shed a halo around the Oriental Church? No less than a hundred martyrs of these later days are commemorated in the services of the Church, and countless are the unnamed ones who have suffered for the faith, in these four hundred years of slavery. In 1821, Gregory, Patriarch of Constantinople, was hung at the door of his cathedral, on Easter Day. Another Patriarch, Cyril, they hung at Adrianople. Cyprian, Archbishop of Cyprus, with his three Suffragan Bishops, and all the Hegumens of the Cyprian monasteries, were hanged upon one tree before the palace of the ancient kings. Many other prelates and prominent ecclesiastics were put to death in the islands and in Anatolia. Mount Athos was devastated. And yet, none apostatized [sic] from the faith of Christ.

Are not such martyrdoms the best way of making converts? It was thus that, in the first three centuries, the Church was founded in those lands. How can it be said that, among people who could so die for the faith, there was no real spiritual life? Has not the Greek Church shown by her deeds the steadfastness of her faith? The kingdom of Greece, in its fifty years of independence, has labored nobly to repair the desolations of many generations. But surely we, who find excuse in the circumstances of the times for the apparent lack of interest of the American [Episcopal] Church in the missionary cause during the first half century of our separate national life, must readily admit that the Hellenic Church has had and still has ample scope for her energies at home.

We come now to the Church of Russia, and what do we find? A large part of what now makes up the Russian Empire was, when it became such, inhabited by Mahometans and heathen. Yet everywhere the Gospel is, and long has been, preached, and God’s blessing has manifestly followed the proclamation of His word. Says Mouravieff, to quote again from Question Religieuse, etc.:

The loving principles of the extension of Christianity are at work here. The Russian Church, as dominant throughout a great empire, diffuses gradually the light of Christ’s Gospel within her own borders. Her more immediate duty is to labor for the conversion of the heathen, Jews, Mahometans and schismatics, who belong to her, scattered over the one-ninth part of the habitable globe. In those dioceses where there are heathen or Mahometans, the languages spoken by them are taught in the theological seminaries, so that, not only those specially devoted to the work, but the parochial clergy also, may be enabled to act as missionaries. Russia has sowed the seeds of Christianity over a vast field, ever establishing new parishes, which most naturally become also mission stations. In this mode of working, there is little to excite attention, or to create talk. When and how have so many of our heathen become Christians? It is not every one who knows. But multitudes of these are now enjoying the blessings of Christianity and civilization. There is yet, however, much to be done for the conversion and establishment in the faith of many tribes, who are more or less in darkness, and the Church still labors for and with them.

But the missions of the Russian Church are not confined to the heathen or false believers within her own borders. For many years she has had a mission at Pekin [Beijing], and the most successful mission work in Japan would seem to be that carried on by her.

If information in regard to Russian missionary work is not forced upon the attention it is yet not unattainable to those who seek for it. The literature of Russian missions is not a small one. The writer, in giving at the head of this paper a list of works now before him, has mentioned but a small part of those bearing on the subject. Let us cast a hasty glance at these. We shall find them filled not so much with talk about missions as with records of faithful missionary work. In the work first mentioned on this list, Mouravieff gives a Compte Rendu d’une Mission Russe, dans les Monts Altai. This paper, one of those translated by Neale, in “Voices of the East,” under the title The Mission of the Altai, describes a most effective work, begun in 1830 and still carried on, amongst wild nomads in the southern part of Siberia.

In the “Remembrancer of the Labors of Orthodox Russian Evangelizers,” Alexander S. Stourdza, a pious layman, began to give a record of missionary work done by the Russian Church, between 1793 and 1853. Mr. Stourdza died in 1854, leaving his work far from complete. The fine octavo volume before us was all that he was enabled to finish. In it he tells of the conversion of two tribes of the Caucusus, about the year 1820. Then he gives the journal of the Archimandrite Benjamin, an earnest missionary among the Samoyedes of Northern Russia, describing their conversion between the years 1825 and 1830. To follow extracts from the journals of other missionaries, two of these being Archimandrite Macarius, the founder of Mission of the Altai and the Arch-priest Landyscheff, who succeeded him in its charge. Then we have described to us the establishment of the Orthodox Church in Russian America, and a selection of letters are published fro the author of that account, Innocent, Archbishop of Kamchatka, to Philaret, Metropolitan of Moscow, to whom Innocent has now succeeded. The remainder of the work tells of missionary labors in the Aleoutine Islands and in Northwestern and Central Siberia. The other publications give more recent missionary intelligence and tell of the present condition of the missionary work.

From such a mass of interesting material it is difficult to make a selection. In setting forth, however, the story of that missionary hero, Innocent, now Metropolitan of Moscow, but for many years Archbishop of Kamchatka, the writer thinks that his subject will be one more than ordinarily attractive to American Churchmen. As Mr. Stourdza believed he could best make his great work of value if, “instead of an artificial narriative, he set before his readers the doings of Russian evangelists, as told at different times, and, for the most part, in the letters of the missionaries themselves, without embellishment or eulogies,” so the aim of the present writer will be to present in a summary form a translation of authentic documents, with the needful connecting and explanatory remarks rather than to tell the story for himself.

One Reply to “The first biography of St. Innocent, part 1”

Comments are closed.