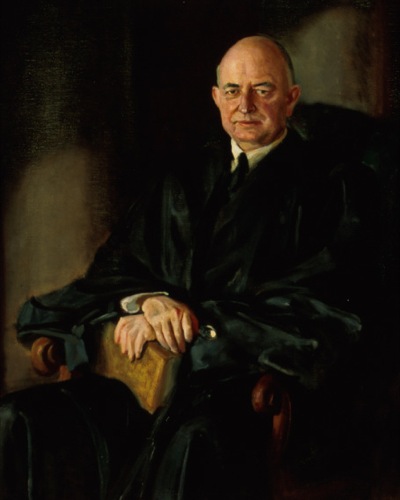

Supreme Court Justice Stanley Reed, author of the majority opinion in Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral

Yesterday, I discussed Justice Reed’s majority opinion in Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral, a landmark 1952 Supreme Court case pitting the Moscow Patriarchate’s North American jurisdiction against the Metropolia (today’s OCA). The dispute was about which group — Moscow or the Metropolia — was the rightful owner of St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York. The majority of the Court ruled in favor of Moscow.

Before moving on to the concurring and dissenting opinions, I wanted to touch on an aspect of Justice Reed’s opinion that I neglected yesterday. Justice Reed devoted a great deal of attention to Watson v. Jones, an 1871 case which served (and still serves) as important precedent in church-state relations. Here are the basics of Watson:

In 1865, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church of the United States denounced slavery and required its members to do the same. In Louisville, Kentucky, the Presbyterians were divided on whether to comply, and the Walnut Street Church ended up in the hands of proslavery members. The parish then joined the Presbyterian Church of the Confederate States. The US General Assembly condemned the proslavery party and, for all intents and purposes, excommunicated them from the Church.

In 1866, some antislavery members of the Walnut Street Church sued for control of parish property. According to Justice Reed’s summary, “The suit was to decide […] which one of the two bodies should be recognized as entitled to the use of the Walnut Street Presbyterian Church.” The Court in Watson held that, “whenever questions of discipline, or of faith, or ecclesiastical rule, custom, or law have been decided by the highest of these church authorities to which the matter has been carried, the legal tribunals must accept such decisions as binding on them.” In this case, the General Assembly of the Presbyterian Church had already recognized the antislavery group as the legitimate owners of Walnut Street Church. The Supreme Court refused to override the decision.

The Court reasoned, in Watson, that if you unite yourself to a hierarchical church, you do so “with an implied consent” to the government of that church, “and are bound to submit to it.” You cannot, said the Court, appeal to secular courts when you don’t agree with a decision of your church. If you could, this “would lead to the total subversion of such religious bodies.”

Justice Reed found obvious parallels between Watson and the present case, Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral. According to Justice Reed, “This controversy concerning the right to use St. Nicholas Cathedral is strictly a matter of ecclesiastical government, the power of the Supreme Church Authority of the Russian Orthodox Church to appoint a ruling hierarch of the archdiocese of North America. No one disputes that such power did lie in that Authority prior to the Russian Revolution.”

In the end, this all seems to boil down to historical interpretation. As I discussed yesterday, the majority’s logic goes like this:

- The Russian Orthodox Church had undisputed authority over the North American Archdiocese prior to 1917.

- The Russian Orthodox Church never relinquished that authority.

- Therefore, the Russian Orthodox Church still has that authority, and its decisions are binding upon the North American Archdiocese (that is, the Metropolia).

Now, it’s true that Patriarch St. Tikhon granted some measure of temporary self-government to the North American Archdiocese. But this grant was not at all clear. Justice Reed doesn’t get into it, but St. Tikhon issued multiple and contradictory decisions during that tumultuous period. And even the strongest, most pro-Metropolia of those decisions was subject to “confirmation later to the Central Church Authority when it is reestablished.” Whatever you think of the Central Church Authority between 1917 and 1945, certainly by 1945 the Metropolia recognized that a legitimate Central Church Authority existed in Moscow. And that authority refused to confirm St. Tikhon’s grant of temporary autonomy for America. Legally speaking, the Metropolia’s position was weak.

As promised, next time, I’ll focus on Justice Frankfurter’s concurring opinion.

This article was written by Matthew Namee.