In an article about Fr. Stephen Andreades, the first resident priest in New Orleans, I quoted from Understanding the Greek Orthodox Church, by Demetrios J. Constantelos (published 1982). At the time, I had only a Google Books “snippet view” of the book, but I’ve since acquired a copy through interlibrary loan, and I thought I’d publish the section dealing with the early Orthodox communities in Galveston and New Orleans. From pages 129-30:

The earliest Greek Orthodox church in the United States was established in 1862 in the seaport city of Galveston, Texas, and it was named after Saints Constantine and Helen. Even though the church was founded by Greeks, it served the spiritual needs of other Orthodox Christians, such as Russians, Serbians, and Syrians. It passed into the hands of the Serbians, who split with the Greeks. The Greeks then established their own church several decades later; but knowledge of the early years of the Galveston Greek Orthodox community is very limited. Neither the number of Greek Orthodox parishioners there nor the name of the first priest is known. The first known Greek Orthodox priest of this community was an Athenian named Theokletos Triantafylides, who had received his theological training in the Moscow Ecclesiastical Academy and had taught in Russia before joining the North American Russian Orthodox Mission. Versed in both Greek and Slavonic, he was able to minister successfully to all Orthodox Christians.

Knowledge of the second Greek community in the United States is more extensive. It was organized in 1864 in the port city of New Orleans. Like the Galveston community, the second one was also founded by merchants. For three years (1864-1867) services were held irregularly and in different buildings. Then in 1867 the congregation moved to its own church structure, named after the Holy Trinity. It was erected through the generosity of the philanthropist Marinos [sic — Nicolas] Benakis, who donated the lot and $500, and of Demetrios N. and John S. Botasis, cotton merchants who together contributed $1,000.

The church was located at 1222 Dorgenois Street and for several years it became the object of generosity not only of Greeks but of Syrians, Russians, and other Slavs. In addition to Greeks, the board of trustees included one Syrian and one Slav. Notwithstanding the predominance of Greeks on the board, the minutes were written in English and for a while it served as a pan-Orthodox Church.

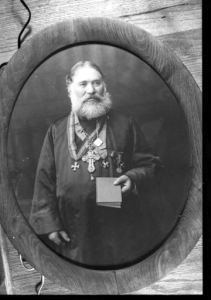

The early Holy Trinity Church was a simple wooden rectangular edifice 60 feet long and 35 feet wide. The major icons of the iconostasis were painted by Constantine Lesbios, who completed his work in February of 1872. The name of the first parish priest is unknown, but it is believed that a certain uncanonical clergyman named Agapios Honcharenko, of the Russian Orthodox mission in America, served the community for three years (1864-1867). In 1867 the congregation moved to its permanent church and appointed its first regular priest, Stephen Andreades, who had been invited from Greece. He had a successful ministry from 1867 to 1875, when Archimandrite Gregory Yiayias arrived to replace him.

The New Orleans congregation also acquired its own parish house; a small library, which included books in Greek, Latin, and Slavonic; and a cemetery.

There’s some good information here, although Constantelos cites no sources, and he gets some important facts wrong. Most crucially, Agapius Honcharenko was in no way connected to the Russian Mission in America, which at the time was limited to Alaska and would later regard Honcharenko as an obnoxious heretic. And Honcharenko did not serve the New Orleans parish from 1864-67 — in fact, he was never the parish priest at all. He visited the community in the spring of 1865, remaining for perhaps two weeks. He did celebrate the first Divine Liturgy in New Orleans, but he was not the first parish priest.

That distinction properly belongs to Fr. Stephen Andreades, but Constantelos gets Andreades’ dates wrong. While he did come to New Orleans in 1867, Andreades was gone by 1872 at the latest; we know this because Fr. Gregory Yayas was the priest by that point.

And before I close, a word about Galveston. First of all, I wouldn’t regard the 1860s Galveston community as a full-fledged “parish.” They had no priest, no known permanent building, and no known affiliation with a bishop. I do believe that a group of Orthodox in Galveston met for prayers under the name “Saints Constantine and Helen.” They may even have been visited by an Orthodox priest traveling aboard a Russian steamer, or something like that. But I regard the pre-Triantafilides Galveston community as a “proto-parish.” In fact, I’m beginning to wonder if New Orleans wasn’t also a “proto-parish” all the way up to 1867. As Constantelos correctly notes, it wasn’t until that year that the community got a priest and a building. Perhaps we should push their founding date up a couple of years, from 1864/5 to 1867?

Anyway, the thing I want to emphasize, because I’ll be coming back to it in other posts in the near future, is that Fr. Theoclitos Triantafilides of Galveston may be The Most Interesting Man in American Orthodox History. Before he came to America, he had lived a full life — as a monk on Mount Athos, as a tutor in the employ of the King of Greece, and later as a tutor to the future Tsar Nicholas II. When he came to the United States, Triantafilides was already in his sixties. When you take into account the changes in life expectancy, that’s equivalent to being in your eighties today. And he lived another two decades, tirelessly serving the Galveston community and beyond, traveling throughout the South in service to the scattered Orthodox people, regardless of nationality. He also appears to be one of the earliest American Orthodox priests to evangelize Protestant Americans (i.e. not only Native Alaskans and Carpatho-Rusyn Uniates).

That’s enough for today, but I assure you that we’ll have more on Triantafilides in the future. In the meantime, be sure to check out Mimo Milosevich’s highly informative website and lecture on the great priest of Galveston.

Hmmm. No offense, but I wouldn’t worry about who’s the “most interesting man.” That will vary from person to person. What I think we ought to be interested in, really, is significance and importance and that is where Archimandrite Theoklitos does seem to shine. He wasn’t St. Tikhon, but was significant, and still may be, for reasons I know you’ll get to later.

That will vary from person to person. What I think we ought to be interested in, really, is significance and importance and that is where Archimandrite Theoklitos does seem to shine. He wasn’t St. Tikhon, but was significant, and still may be, for reasons I know you’ll get to later.

Well, I did say that he “may be” the most interesting man. But the point, as you know, is that Triantafilides is a unique figure worthy of a great deal of attention today. If we define historical significance as being impact on the course of history, then Triantafilides isn’t very high on the list of most significant American Orthodox figures. But I think (and I know you do too) that historical significance goes beyond mere “impact.” And I think (and I know you do too) that Triantafilides is a VERY significant figure.

Anyway, for my money, I’ll take Triantafilides as the most interesting man. Granted, that’s not really an important distinction, and it’s entirely subjective. But the man was born in Greece, lived on Mount Athos, worked for the Greek king, tutored the last Russian tsar, and at retirement age, he moved to Galveston, TX (of all places) and served a multiethnic Orthodox parish with great success. Not sure who, in American Orthodox history, tops that

Fair enough. Yes, one can be significant in terms of the impact made and one can be significant in terms of “exemplar,” and I think, at this point at least, that Archimandrite Theoklitos fits the latter category. At this point, barring something unseemly, I think he’s downright inspiring!