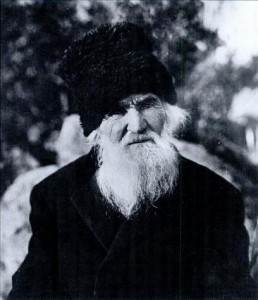

Note: Last week, we met Fr. Agapius Honcharenko, who served the first known Orthodox liturgies in New York (or, for that matter, the United States of America — remember, this is when Alaska was still part of the Russian Empire). (Click here to read that article.) Today, we continue the story, focusing on Honcharenko’s life before his arrival in America.

What you think about Agapius Honcharenko’s origin story depends on whom you believe – the Russian Orthodox Church of the time, or Honcharenko himself. But certain things seem fairly undisputed, so let’s lay out the agreed-upon facts first:

- Honcharenko was born in August 1832 in the Russian Empire, in what is now Ukraine. Modern scholars agree that his given name was “Andrii Humnytsky.”

- He studied at the Kiev Theological Academy and then became a monk at the Kiev Caves Lavra in 1856.

- The next year, he became a hierodeacon (with the name Agafy) and was assigned to serve at the Russian embassy chapel in Athens, Greece.

- In 1860, he was accused of various things and removed from his post in Athens. Everyone agrees that one of those things was secretly writing anti-Tsarist and anti-Church articles for a left-wing Russian journal called Kolokol, which was published out of London.

- The Russian government took him into custody and tried to send him back to Russia by way of Constantinople, but he escaped and made his way to England, where he collaborated with the publisher of Kolokol. It appears to be at this point that he started using the pseudonym “Honcharenko.”[1]

- At some point, he went back to Greece, claims to have been ordained a priest, and then sailed for America, arriving in early 1865.

Those are the facts, as best I can tell. The details are where things get a little hazy.

According to Honcharenko himself (in an account by an admiring journalist who visited him in 1911), “From early childhood he had observed the oppression of the serfs and their liberation had become the dominating impulse of his life.”[2]

We get a different perspective from the former Russian Ambassador to Greece, paraphrased in an Russian Church report from 1865: “The basic idea directing Agafy’s life was that all in the world is a convention and that everything can be understood whatever way one wants to. As a result of this, Agafy had a secret opposition to everything legal and generally accepted. He rejected all order and was repulsed by every constraint. This attitude brought him to the deepest and dirtiest amorality.”[3]

So – heroic abolitionist, or amoral anarchist? Perhaps both. It’s hard to tell.

Everyone agrees that the young hierodeacon secretly wrote for the revolutionary journal Kolokol until he was found out in February 1860 – caught, according to Honcharenko, in the act of mailing a manuscript to Kolokol’s editor. He was immediately arrested and shipped off to Russia.

What Honcharenko doesn’t say, in any of his accounts, is that he was also accused of inappropriate behavior with a teenage boy. According to the aforementioned 1865 Russian Church report, in January 1860 (so, a month before then-Hierodeacon Agafy was caught mailing the Kolokol manuscript), a boy of about 16 declared that the hierodeacon had, for a long time, “hounded him with impolite words and at last made an improper proposition.” Hierodeacon Agafy didn’t deny this, but instead claimed that he was actually trying to find out if the Embassy church rector had been doing the same thing. It was all part of a trap, see? Agafy wasn’t actually propositioning the kid, he said.

Then – again, following the Russian Church account – Agafy went on the offensive against the Embassy church rector, spreading written slander about him locally and also publishing it in Kolokol. Only at that point (so says the Russian Church report) was the hierodeacon taken into custody.

Again, which was it – was he arrested for secretly writing revolutionary, anti-serfdom articles? Or for propositioning a teenager and publishing allegations against the rector? Maybe all of it.

So Agafy was arrested, and the Tsarist government was taking him back to Russia, presumably to stand trial. But when the ship passed through Constantinople – and everyone agrees on this – Agafy slipped out of his clerical attire and fled to London. Honcharenko’s own version of the story is amazing: Chained in a Russian dungeon in Constantinople, he was rescued when a Polish Jew, peddling oranges in Constantinople, smuggled Turkish clothing into the prison. From Honcharenko himself: “I will never forget that day I took off my priest’s robes, put on the Turkish costume, and passed out before the faces of the guardians of the prison, and escaped to London. Since then, by Muscovite tyrants, I have been stabbed, shot, drugged, assaulted with brass knuckles, and even clubbed as a dog. I am yet alive, and as a true Cossack, labor to free my people.”[4]

In London, he kept writing for Kolokol, under the pen name “Honcharneko.” The Holy Synod of Russia defrocked him in August 1861. It wasn’t too long before the former hierodeacon returned to Greece and continued his vendetta against the Athens Embassy rector. For a time, he was in a Greek monastery, and this appears to be when his purported ordination to the priesthood took place. A modern scholar, Jars Balan, writes that Honcharenko was ordained a priest “in a Greek Orthodox Monstery at Mount Athos” on February 25, 1862. Balan doesn’t mention which monastery, and I’ve never seen hard evidence for an ordination. (In 1866, the journal Union Chretienne, a Paris-based Orthodox journal published by the convert priest Fr. Vladimir Guettee, claimed that Honcharenko’s ordination was “irregular” – whatever that means.)[5]

The Russian government kept trying to have him brought back to Russia, with no success. The Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs explained that they couldn’t forcibly return Honcharenko to Russia. According to Balan, at some point Honcharenko visited Jerusalem, “narrowly evading rearrest there by Russian authorities” with help from the holy city’s Roman Catholic patriarch, and hid out in a Jesuit monastery in Lebanon. Then he went to Egypt, got a job as a salesman, was noticed by the Russians again, and, according to Balan, “In February 1863 an Ionian Greek in the hire of the Russian consul attacked Honcharenko with a knife as he was working in his kiosk at the Cairo railway station.”

I can’t confirm that this actually happened, and maybe it didn’t. But there’s a somewhat ambiguous line in the 1865 Russian Church report, saying that the Foreign Ministry “asked our Ambassador in Athens to look for ways to remove Agafy from Greece.” What sort of ways? Ways involving a knife-wielding Ionian in Cairo? Or is that just a fish story from Honcharenko, years after the fact?

The timeline is a little unclear, but all this is happening in the early 1860s. In September 1863, in the middle of the U.S. Civil War, a fleet of Russian ships arrived in the New York harbor. The ships’ chaplains were Orthodox priests, and although they didn’t serve the Divine Liturgy in America, they did baptize some Greek children, and on their return trip to Russia, one of the ships stopped in Athens, where they shared news of Orthodox people in America who needed a priest.[6] It seems that this is where Honcharenko got the idea to travel to America, far from the clutches of the Russian government.

For their part, the Russians – church and state – seem to have lost track of Honcharneko. That is, until reports started appearing about Orthodox liturgies taking place in New York City.

Footnotes

[1] This is reported in Jars Balan, “California Dreaming: Agapius Honcharenko’s Role in the Formation of the Pioneer Ukrainian-Canadian Intelligentsia,” Journal of Ukrainian Studies vols. 33-34 (2008-09), page 62. Balan appears to rely on Honcharenko’s autobiography, Spomynky (Edmonton: Slavuta, 1965).

[2] San Francisco Call, April 9, 1911. In Honcharenko’s later decades, numerous journalists made the trek to his ranch, near Oakland, California. They were uniformly enamored with the intriguing Cossack priest who claimed to have fought for liberty and evaded Tsarist assassins. For example, see Washington Post (April 20, 1890), Chicago Tribune (December 4, 1892), Los Angeles Times (December 22, 1895), New York Sun (April 9, 1899), and Oakland Tribune (March 30, 1913).

[3] The Russian Church report is undated, but appears to have been written in 1865, and was found by Nicholas Chapman in the National Archives in London, along with the previously-cited letter from St. Philaret of Moscow to the Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod, dated February 26, 1865 (Julian Calendar). The 1865 report was translated by Matushka Marie Meyendorff and published at OrthodoxHistory on September 7, 2010 (https://www.orthodoxhistory.org/2010/09/07/agapius-honcharenko-in-defense-of-himself/).

[4] San Francisco Call, April 9, 1911.

[5] Union Chretienne article summarized in “Another Attempt at Union Between the Anglican and Greek Churches,” Catholic World, vol. 2, no. 7 (October 1865), page 67.

[6] This is briefly summarized in my article, “Two Russian Priests in New York City, 1863,” at OrthodoxHistory.org, July 28, 2009 (https://www.orthodoxhistory.org/2009/07/28/two-russian-priests-in-new-york-city-1863/). For additional information, see Marshall B. Davidson, “A Royal Welcome for the Russian Navy,” American Heritage Magazine 11:4 (June 1960) and Edward W. Ellsworth, “Sea Birds of Muscovy in Massachusetts,” New England Quarterly 33:1 (March 1960), 3-18. A contemporary account of the 1863 baptisms may be found in the New York Times, September 30, 1863, page 5.

Leave a Reply