Back in March, I published a 9-part series on the global Orthodox crisis of 1917-1925. I’ve made a few revisions to that account and added an Epilogue and a partial bibliography. Today, I’m publishing all of that — 9,000+ words, altogether.

Orthodoxy is currently facing a global crisis of unity. While we might be tempted to despair of the well-being of the Church, it is helpful to remember that, not so long ago, Orthodoxy faced a series of threats that were arguably more threatening than the present crisis.

The 1917-25 period – admittedly, those are arbitrary endpoints – is impossibly complicated, and I can’t pretend I’ve wrapped my head around all of it. Frankly, I’m not sure if anyone has – I’m not aware of any other attempt to study Orthodox history in this era in a holistic fashion. This paper is hardly an authoritative treatment of those tumultuous years; what I’m attempting is to present the highlights (and lowlights) in chronological order, to help us better understand what Orthodoxy as a whole was facing. If the 19th century is the beginning of the modern era of Church history, when nationalism entered Church life, then 1917-25 is the incubator that took the embryonic changes of the 19th century and birthed the Orthodox context we live in today.

I’ll warn you right now – there’s a LOT about this period that I don’t understand, or may have missed, or have insufficiently summarized. I welcome corrections, clarifications, etc. I don’t have an agenda here, other than to convey a sense of the turmoil that engulfed the Orthodox Church a century ago.

1917

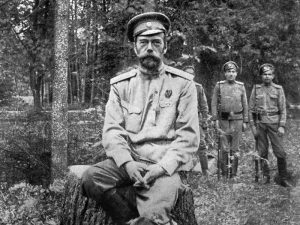

In February 1917, as World War I raged, a revolution in Russia toppled the great Romanov dynasty. The Tsar and his family were kept under house arrest. Until the second revolution in October of this year when the Bolsheviks seized total power, more moderate elements nominally controlled the Russian state, and the Orthodox Church was not yet overtly persecuted.

In the wake of the February Revolution, the bishops of the Georgian Orthodox Church declared themselves autocephalous and independent from the Russian Church, which had suppressed Georgia’s ancient autocephaly a century earlier.

That spring, over in America, the Syrian/Antiochian community split into two factions, with one group favoring the newly consecrated, Russian-backed Bishop Aftimios Ofiesh, and the other group pledging allegiance to Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi, a visiting bishop from the Patriarchate of Antioch.

The Patriarchate of Antioch itself had been suffering from a devastating famine for the past three years, caused by a combination of an Allied blockade of the Eastern Mediterranean, Ottoman disruption of railroad transportation, and (as if that wasn’t enough) a literal plague of locusts. In May of 1917, an American in Beirut named Edward Nickoley wrote, “Starving people lying about everywhere; at any time children moaning and weeping, women and children clawing over rubbish piles and ravenously eating anything that they can find. When the agonised cry of famishing people in the street becomes too bitter to bear, people get up and close the windows tight in the hope of shutting out the sound. Mere babies amuse themselves by imitating the cries that they hear in the streets or at the doors.”

Meanwhile, Greece was deeply divided between royalist supporters of King Constantine and followers of Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. In June, under great pressure, King Constantine abdicated the throne in favor of his son, Alexander. A (for now) unified Greece joined the Great War on the side of the Allies.

In October, a second revolution, led by Vladimir Lenin and his Bolsheviks, overthrew the secular Provisional government in Russia and installed a violently anti-Christian communist regime. Just as the Bolsheviks were storming Moscow and taking the city by force, an All-Russian Sobor was meeting in the city. The Sobor re-established the Moscow Patriarchate and elected St. Tikhon as Patriarch, just days after the Bolsheviks took control of Moscow. Shortly after the Bolsheviks seized power, they killed the first hieromartyr of the Revolution – St. John Kochurov, formerly the parish priest of Holy Trinity in Chicago, and in 1917 dean of a cathedral near St. Petersburg.

The same week, over in England, the British government issued the Balfour Declaration, calling for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. On November 1, as the approach of the British army on Palestine was imminent, the Turkish government removed the Patriarch and Holy Synod of Jerusalem to Damascus, despite the objections of the Holy Synod.

The Patriarchate of Jerusalem was then (as it is now) controlled by the ethnically Greek “Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre” despite the fact that its flock consists mainly of native Palestinians. The British military governor who took charge of Palestine at the end of 1917 wrote of the Brotherhood:

“The attempt to preserve it as less the Church of the Palestine Orthodox than as an outpost of Hellenism… was the source not only of constant intrigue and wire-pulling… but also of increasing discouragement and bitterness to the Orthodox Arabs of the country.

“The Adelfotis – the Orthodox Brotherhood – is an absolutely closed corporation: there were not Arab Metropolitans, Bishops or even Archimandrites, and a modern Arab Patriarch (though there have been such in the remote past) was about as probable a prelate as an English Pope.”

The Brotherhood had done a terrible job managing the finances of the Jerusalem Patriarchate, and by 1917, it was in debt to the tune of roughly $700,000 (over $13 million in modern terms).

The Bulgarian Orthodox Church had broken away from the Ecumenical Patriarchate in 1870 and was formally condemned at a council in 1872 – the council that condemned “phyletism.” This schism wasn’t healed until 1945. Throughout this period, the Bulgarian Orthodox were out of communion with many of the Orthodox Churches, although not all – the Bulgarian Church received Holy Chrism from the Churches of Romania and Russia, and remained in communion with the Serbian Church, despite having been anathematized by the 1872 Council of Constantinople. To complicate matters further, after the death of its primate in 1915, the Bulgarian Church was without a leader for the next three decades.

1918

It is difficult to summarize what was going on in Russia with any sort of brevity. In February 1918, Patriarch Tikhon excommunicated the Bolshevik leadership; a few days later, Vladimir Lenin issued a decree that deprived the Russian Orthodox Church of its legal status, the right to own property, and the right to teach religion in schools or to children. Civil war between the Bolshevik Red Army and the anti-communist White Army tore the country apart for five years following the Bolshevik seizure of power in late 1917. An estimated 7-12 million people died in the Civil War, most of them civilians. Here are a handful of examples of the Bolshevik attacks on Orthodoxy in 1918 alone. (Many of these accounts are summarized in Dimitry V. Pospielovsky, A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol. 2: Soviet Anti-Religious Campaigns and Persecutions, St Martin’s Press, New York (1988).)

In January, Metropolitan Vladimir of Kiev was the first bishop to die a martyr at the hands of the Bolsheviks – he was beaten and tortured before being shot. His final act was to pray for his killers’ forgiveness. In February, on elderly hieromonk was beaten with rifle butts before being killed. Another priest was taken to a cemetery and stripped naked, and when he tried to make the sign of the Cross before being executed, a soldier cut off his right arm. Still another priest tried to stop the execution of a peasant, but was beaten and hacked to death with swords. An abbot was scalped before being beheaded. A priest in the Diocese of Kherson was crucified. Another elderly priest was dressed as a woman and told to dance in the village square; he refused and was hanged.

In July, the Bolsheviks drowned Bishop Hermogenes of Tobolsk and his companions: rocks were attached to the bishop’s head and he was thrown into the water. The next day, the Bolsheviks murdered the imprisoned Tsar Nicholas II and his family. Twenty-four hours after that the Tsarina’s sister, by then the Abbess Elizabeth and her attendant the nun Barbara were also slain. In Voronezh, seven nuns were boiled in a cauldron of tar. Archbishop Joachim of Novgorod was hanged upside down over the Royal Doors on the iconostasis. Over fifty priests were murdered in the Diocese of Stavropol alone; another 42 were killed in the Diocese of Perm. In Perm, the Bolsheviks cut out the eyes and cheeks of one priest, paraded him through the streets, and then buried him alive.

All of this was happening before the so-called “Red Terror” began in August. In the second half of 1918, an estimated 102 priests, 154 deacons, and 94 monastics were executed by the Communist regime.

In the wake of the revolutions in Russia, the financial state of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem went from bad to worse – the Patriarchate had long been dependent upon Russian financial support, which was cut off once the Tsar was overthrown. With Russian money and pilgrims no longer flowing into Palestine, Orthodox schools and other institutions were forced to close. Furthermore, the Patriarchate was cut off from income from its property holdings in Bessarabia and Wallachia. In May 1918, the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre declared its intentions to hand over full control of the Patriarchate’s administrative and financial affairs to the Greek government, which insisted upon the deposition of Patriarch Damianos. The Brotherhood complied, and in September, they deposed Damianos. However, the British government, which controlled Palestine, would not recognize Damianos’ deposition and wouldn’t allow the Greek government a free hand in the Patriarchate. The British did arrange for the sale of many properties of the Patriarchate – and many of the buyers were Jewish companies. This was the beginning of the sell-off of Orthodox lands to Jewish settlers – a problem that has continued to plague the Patriarchate to this day.

Over in Constantinople, in October, Ecumenical Patriarch Germanus V’s own flock rose up against him due to his authoritarian approach to church governance and his failure to defend the Orthodox people who were being persecuted by the Turkish government. Germanus condemned the rebellion, but he ultimately resigned on October 12. The Ecumenical throne would remain vacant for the next three years. In November Constantinople was occupied by a coalition of British, French and Italian forces who would remain there for almost five years.

In the Patriarchate of Antioch, the entire region had been a war zone for the past two years, as the Arab Revolt, begun in 1916, aimed to create a single, unified Arab state. Famed British writer T.E. Lawrence – “Lawrence of Arabia” – was a key figure on the Allied side in this conflict. On October 1, Allied forces captured Damascus. A few days later, Emir Faisal, with British support, announced the establishment of an independent Arab state.

Following the Great War, Poland achieved its independence, and the new government set about establishing a new Polish state with a national unity based on Roman Catholicism. There was no place in that vision for a Polish Orthodox minority, and the government set about confiscating Orthodox property and handing it over, either to the Uniates (“Greek Catholics”) or directly to the Roman Catholic Church. Some 400 Orthodox churches were confiscated in the period from 1918-1924, and others were completely demolished. In some cases, churches were simply turned into junkyards, warehouses, or cinemas. In most of these cases, the state didn’t even bother removing the altar or icons.

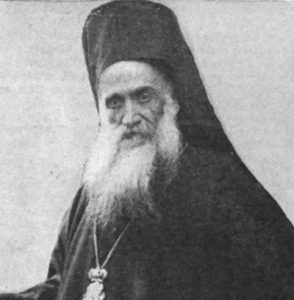

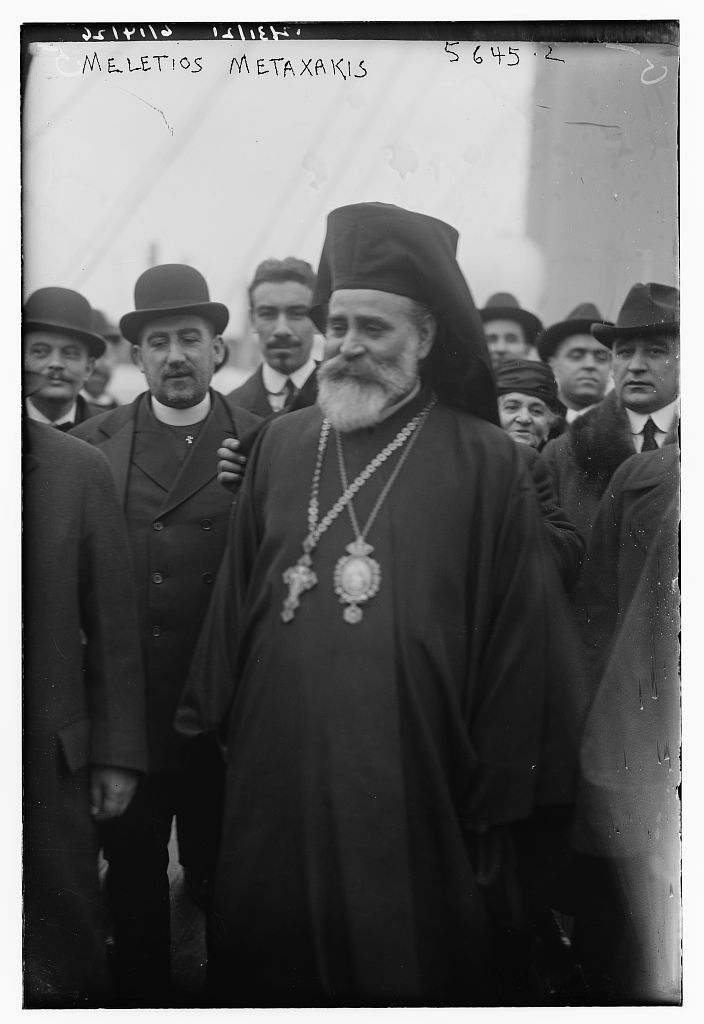

With Prime Minister Venizelos in power in Greece, his close ally, the controversial hierarch Meletios Metaxakis, was elected Archbishop of Athens and primate of the Church of Greece. Archbishop Meletios immediately set sail for America, and in October, he created the Greek Archdiocese of America (yes, in 1918, not 1921 as is commonly reported).

On December 1, in Belgrade, the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats, and Slovenes was proclaimed. In time, this new country came to be known as “Yugoslavia”(“South Slavs”). It was a near-inevitability that, eventually, this political union would lead to an ecclesiastical union of the various Serbian Orthodox bodies in the new territory of Yugoslavia.

While all this was happening, throughout 1918 and for some time afterward, the world was beset by the “Spanish Flu” pandemic, which killed an estimated 20-50 million people worldwide.

1919

In January 1919, the British reinstated the deposed Damianos as Patriarch of Jerusalem. The Jerusalem Patriarchate’s financial crisis continued.

Also in January, in Estonia, Bolshevik soldiers killed some twenty clergymen, including Bishop Platon of Tallinn.

Beginning in January, the Allied Powers met in Paris to negotiate the terms of peace following the Great War. All kinds of big things happened at the conference, many of them directly affecting the Orthodox Church. In February, the Zionist Organization submitted a formal proposal to create a Jewish state in Palestine. In April, the League of Nations was formed.

Ukraine was torn apart by continued violence – in the western part of the region, Eastern Galicia was annexed by Poland, an act that was blessed by the Allied Powers at the Paris Peace Conference. Meanwhile, Bolshevik troops overran eastern and central Ukraine. Belarus had declared itself independent of Russia in 1918, but that independence wasn’t recognized by most of the world, and the country became a battleground for Polish and Bolshevik aggression.

Greek Prime Minister Venizelos was one of the most prominent figures at the Paris Peace Conference, and he pushed for Greece to acquire new territory. In May, the Greco-Turkish War began, as Greek troops began landing in Smyrna. Within days, the Turkish Revolution broke out, led by Ataturk, which ultimately resulted in the end of the Ottoman Empire.

In Russia at this point, the Communist leaders were making blasphemously creative efforts to undermine the Orthodox Church. In the Caucuses, they staged a mock “wedding” between an elderly priest and a horse, forcing the choir to sing the Orthodox wedding hymns under threat of death. In Moscow, they published a parody of the Orthodox funeral service, for a dog. In a church in the North Caucuses, they bayoneted the mouth of Christ in an icon and inserted a cigarette. In some churches, the Communists desecrated the holy spaces by holding drunken orgies. During this period of persecution, numerous saints’ relics were seized by the Communists, who tried to “expose” them as fraudulent.

The Bolsheviks weren’t just mocking the Church, though – their murderous rampage continued, as well. In Kharkov, a priest was executed for criticizing the Bolsheviks, and when his wife came to retrieve his body, the Bolsheviks dismembered her (while still alive), pierced her breasts, and then executed her. In another incident, an elderly priest was tied to a telegraph pole and shot to death, and his body was fed to dogs.

In May 1919, the Pan-Syrian Congress, the first-ever national parliamentary body in Syria, met in Damascus.

In July, Metropolitan Dorotheos of Prusa, Locum Tenens of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, gave an interview with a Western journalist in which he said, “[O]ne Christian Church ought not to be wasting its energies trying to take converts from another Christian Church. All Christian churches ought to unite to lead the world out of darkness. We need a League of Churches as well as a League of Nations.”

In August, a Serbian clergy union held an assembly, which appealed to the Serbian Church to permit the remarriage of widowed clergy. This had been a major topic of discussion for the better part of a decade, but it became a particularly big deal after the Great War, which left many priests as widowers.

In November, Greece and Bulgaria signed an agreement providing for the “reciprocal voluntary emigration of the racial, religious, and linguistic minorities in Greece and Bulgaria.” In the years following 1919, practically all of the Greeks of Bulgaria – some 46,000 people – left Bulgaria and immigrated to Greece. On the other side, 92,000 Bulgarians left Greek territory for Bulgaria.

As part of a series of postwar treaties, the Romanian state was united with Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina, to form Greater Romania. The Romanian Orthodox bishops in all these lands united in a single Romanian Orthodox Church, and at the end of December, they elected Metropolitan Miron of Transylvania as their primate.

1920

In January 1920, the Ecumenical Patriarchate issued an encyclical “Unto the Churches of Christ everywhere,” calling for the “rapprochement between the various Christian Churches” and the establishment of a “League of Churches” (echoing the words of the Patriarchal Locum Tenens the previous July). Even more radically, the encyclical called on “the churches” (making no distinction between Orthodox and heterodox) to “no more consider one another as strangers and foreigners, but as relatives, and as being part of the household of Christ and ‘fellow heirs, members of the same body and partakers of the promise of God in Christ.’” By treating the heterodox as also being “members of the same body” as the Orthodox, the Ecumenical Patriarchate inaugurated a new era in “ecumenical” relations.

Meanwhile, in the wake of Britain’s Balfour Declaration and the rise of Zionism, Jewish migration to Palestine was on the rise. This led to conflicts with the native Palestinian population, and, in April, to the Nebi Musa riots in Jerusalem.

Nearby, in Syria, the Syrian Congress proclaimed an independent Arab Kingdom of Syria in March, with King Faisal as the monarch. The British and French immediately rejected this, and in April, the League of Nations established the French mandate for Syria, giving France control over the region. Patriarch Gregory of Antioch threw his support behind King Faisal and swore allegiance to him. But facing a superior French army with the backing of the League of Nations, King Faisal surrendered in July. On July 24, French troops entered Damascus and declared the Syrian Kingdom to be disbanded. Soon, Syria – and thus the core territory of the Patriarchate of Antioch – was divided by the French into three entities: Syria, Lebanon, and Hatay (after they failed in their attempt to also carve out Alawite and Druze states). This division was damaging to the Patriarchate, which had its population relatively evenly distributed between the three new states.

In June, the Orthodox jurisdictions in Yugoslavia were united into a single Serbian Orthodox Church. In September, the Serbian Church held a Council of Bishops, which decided to reestablish the Patriarchate of Serbia. Shortly after this, Metropolitan Dimitrije of Belgrade was elected Patriarch. The Serbs began negotiating with the Ecumenical Patriarchate for recognition of their autocephaly, and one of the topics discussed in those negotiations was clergy remarriage. Bishop Nicholaj Velimirovic – author of the Prologue from Ochrid collection of saints’ lives, and later canonized a saint himself – was a leading figure in these negotiations for the Serbian side, and was reportedly an advocate of clergy remarriage.

While all this was happening, in September, the exiled Russian Metropolitan Antonii Khrapovitskii (one of the three finalists for Patriarch of Moscow a few years earlier) was on Mount Athos and received a telegram from a general in the Russian White Army, asking him to come to the Crimea and oversee the Russian Orthodox people there. Metropolitan Antonii complied, but within forty days, the situation was untenable, and 150,000 Russians, including numerous bishops and priests, boarded ships headed for Istanbul.

Back in August, royalist soldiers failed in an attempt to assassinate the Greek Prime Minister Venizelos. Two months later, King Alexander died of blood poisoning caused by a monkey bite. This occurred only days before the next round of elections, in November, which turned into a referendum on the monarchy. The Venizelist faction was defeated, and the exiled King Constantine – who had abdicated back in 1918 – was recalled to Greece. After this, other countries declared their neutrality in the Greco-Turkish War, leaving Greece isolated. With his ally Venizelos defeated, Archbishop Meletios Metaxakis was no longer welcome in Athens; however, he was conveniently in the United States at the time, in the process of organizing the Greek Archdiocese of America.

While all this was happening, on November 8, the great wonderworking bishop, St. Nektarios of Aegina, died of prostate cancer. Three days before St. Nektarios’ death, in Turkey, the future St. Iakovos of Evia was born. His first five years of life were filled with turmoil – his father was taken captive by the Turks before Iakovos turned two, and then his family was forced to leave their homeland as part of the “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey.

The fleet of Russian exiles, led by Russian Metropolitan Antonii and numerous other bishops arrived in Istanbul on November 19. That day, aboard a ship, they held the first meeting of what was then called the Higher Church Administration Abroad – what eventually became known as the Russian Orthodox Church Outside of Russia (ROCOR). According to some sources – although this is disputed by others – the following day, Patriarch Tikhon formally granted permission for ROCOR to be organized. What isn’t disputed is that, on December 2, the Locum Tenens of the Ecumenical Patriarchate authorized the exiled Russian bishops to establish “a temporary committee under the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarchate” to administer the Russian Orthodox communities in exile.

1921

In February 1921, the Red Army invaded Georgia, capturing Tbilisi and then the rest of the country. The communists declared the “Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic” and began a mass persecution of the Orthodox Church in the country.

Also in February, Patriarch Dimitrij of Serbia invited the leaders of ROCOR to relocate from Istanbul to Serbia. ROCOR leadership formally decided to accept the invitation in April. Meanwhile, also in February, the Serbian clergy union held an assembly and renewed their call for the Church to allow widowed clergy to remarry.

In March, Metropolitan Dorotheos, the powerful Locum Tenens of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, died in London.

In the spring of 1921, Russia, having already been devastated by three years of civil war and Bolshevik rule, was beset by a brutal famine that lasted for the next two years, killing an estimated 5 million people.

In April, Patriarch Tikhon appointed Metropolitan Evlogy Georgiyevskiy to administer the Russian Orthodox parishes in Western Europe.

In May, as Jewish migration to Palestine continued, deadly riots broke out in Jaffa and spread throughout the region. Shortly after this, Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem attempted to call a Holy Synod meeting, but only a portion of the members of the Holy Synod heeded the summons. In response to the continued dissension among the Holy Synod and the ongoing financial crisis facing the Patriarchate, on June 17 the British government in Palestine issued a decree, essentially expelling all of the Patriarch’s opponents from the Holy Synod and setting up a British commission to manage the financial affairs of the Patriarchate.

In June, Metropolitan George of Warsaw, primate of the Polish Orthodox Church, signed an agreement with the Polish government to establish the Church of Poland, in opposition to the Russian Orthodox Church that claimed Poland as part of its canonical territory. Three Polish bishops opposed this action, and, according to news reports, Metropolitan George had them deposed and banished to monasteries.

In July, ROCOR leadership completed its move to Serbia and held its first meeting there. On August 31, the Council of Bishops of the Serbian Orthodox Church officially decided to take ROCOR under its protection.

In September, Archbishop Meletios Metaxakis presided over the first-ever Clergy-Laity Congress of the newly reconstituted Greek Archdiocese of America.

In October, a group of Ukrainian clergy and laymen – but no bishops – gathered in an “All-Ukrainian Sobor” and attempted to create an autocephalous church. This group purported to consecrate their own hierarchy, themselves, although none of them were actually bishops to begin with, making it totally impossible to establish anything resembling a legitimate hierarchy, even in external form.

In late November, ROCOR held its first-ever All-Diaspora Council, in Sremski Karlovtsi, Serbia. There were 155 official participants, including the Patriarch of Serbia, who was given the title of honorary president.

Meanwhile, on November 27 – while the first ROCOR council was taking place – the Ecumenical Patriarchate finally held an election to fill its long-vacant throne. Out of the 68 bishops entrusted with a vote, only 13 were present at the meeting, while 5 more gave their vote to one of those 13 attendees. So that left 18 votes, and 16 went to Meletios Metaxakis, Archbishop of Athens, who was in America in a sort of quasi-exile.

Seven of the absent bishop-electors were metropolitans who comprised a majority of Constantinople’s 12-member Holy Synod of Constantinople. These metropolitans gathered in Athens and refused to recognize Meletios’ election as valid. They sent a telegram to Meletios, who was in America, ordering him not to come to Constantinople. He ignored the telegram. Meanwhile, the Holy Synod of the Church of Greece deposed him. Meletios ignored that, too.

1922

As 1921 turned to 1922, the Church of Greece rejected the election of Meletios Metaxakis as Ecumenical Patriarch, and formally deposed him. Ignoring this, in February, Meletios was enthroned in Constantinople. One of Meletios’ first acts, in March, was to issue a Tomos declaring the right of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to “direct supervision and management of all Orthodox parishes located outside the borders of the Local Orthodox Churches, without exception, in Europe, America, and other places.”

Meletios was busy in March – in addition to the landmark Tomos regarding the Orthodox globally, he issued a Tomos of Autocephaly to the Church of Czechoslovakia. The same month, he spent a week negotiating with a Serbian Orthodox delegation regarding the autocephaly of the Serbian Orthodox Church.

Meanwhile, also in March, Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow issued a document formally thanking Patriarch Dimitrije of Serbia for his hospitality to the Russian emigres – one of many in a confusing series of documents from Patriarch Tikhon, sometimes blessing the work of ROCOR, sometimes objecting to it.

In early April, Vladimir Lenin arranged for Joseph Stalin to be appointed General Secretary of the Communist Party in Russia. Stalin would hold the position for the next thirty years.

Later that month, the communist authorities in Russia – which was still in the midst of a famine – placed Patriarch Tikhon under house arrest. Shortly after this, Tikhon testified at a show trial put on by the Soviets against a group of Orthodox clergymen who had refused to give up sacramental objects – chalices, communion spoons, etc. – to the government. At the end of his testimony, Tikhon concluded, “I bless the faithful servants of the Lord Jesus Christ to suffer and die for Him.” The clergy were then taken away to be executed. All told, some 8,000 Orthodox Christians are estimated to have been killed in 1922 alone, during the conflict over church valuables.

The same month, the schismatic, renovationist “Living Church” was started in Russia, with support from the Soviet government.

Also in April, the legitimate Russian Holy Synod appointed Metropolitan Platon Rozhdestvensky as the temporary head of its North American Archdiocese. Metropolitan Platon, who had previously led the Archdiocese before transferring to another see in 1914, had returned to America as a refugee from Russia in 1919. The Archdiocese held an All-American Sobor later that year, electing Platon as the head of what became known as the “Russian Metropolia” (and is now the OCA).

In May, Lenin suffered a massive stroke that left him nearly paralyzed. The same month, the Communist government coerced the Russian Holy Synod to issue a decree abolishing ROCOR. The decree was not signed by Patriarch Tikhon. ROCOR had to quickly regroup and obtain additional authorization for its existence.

Also in May, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios issued a Tomos, formally transferring the Greek Archdiocese of America from the jurisdiction of Athens to that of Constantinople.

In July, the League of Nations adopted the Balfour Declaration, calling for the creation of a Jewish state in Palestine. The League granted the famed “British Mandate for Palestine,” which ultimately led to the creation of the state of Israel.

Also in July, a Soviet tribunal sentenced Metropolitan Benjamin of Petrograd and several other Orthodox Christians to death, ostensibly for counter-revolution and for opposing the seizure of holy objects. In August, the saintly Metropolitan – shaved and dressed in rags to conceal his identity from the soldiers who would kill him – was taken outside the city and executed by firing squad. In 1992 the Russian Orthodox Church glorified him.

Also in August, reports circulated worldwide that the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, led by Patriarch Meletios, had declared Anglican holy orders to be valid. The Episcopal Church of America held its national conference in Portland, Oregon in September, and numerous Orthodox bishops attended. Patriarch Meletios sent a letter to the conference, announcing his decision to recognize Anglican orders. (This same Episcopal Church conference was the pretext for the arrival in America of a delegation from the Patriarchate of Antioch, which went on to establish the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America.)

Also in September, the Greek army lost the city of Smyrna to the Turks, and the subsequent Great Fire of Smyrna destroyed the Greek and Armenian quarters of the city, killing thousands. Metropolitan Chrysostomos of Smyrna was captured by the Turkish army, handed over to a mob, and lynched in the presence of French soldiers who were under orders not to intervene. (In 1992 the Church of Greece glorified him.) The Turks massacred and deported untold thousands of Orthodox Christians during these war years.

Before the month was over, the Greek military rose up against King Constantine’s government, expelling Constantine and declaring his son George to be king. The new government reversed the state’s position on Patriarch Meletios and ordered the Church of Greece to recognize him as Ecumenical Patriarch. The Archbishop of Athens refused, and was deposed.

Also in September – it was a busy month – in Albania, an Orthodox congress was held to establish an autocephalous Albanian Orthodox Church. The congress proclaimed the Albanian Church as autocephalous and elected Metropolitan Fan Noli as its primate. Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios responded by sending a patriarchal exarch to investigate. The exarch congratulated the new Albanian Holy Synod and recommended that the Ecumenical Patriarch invite an Albanian delegation to Constantinople.

In October, Patriarch Meletios told an Italian reporter that it might be necessary to move the Ecumenical Patriarchate to Mount Athos. The same month, the Holy Synod of Constantinople met twice to consider moving the Patriarchate out of Turkey.

In November, the Lausanne Peace Conference began. This ultimately led to the Treaty of Lausanne, which had far-reaching effects on the Ecumenical Patriarchate and on Greek Orthodoxy in general, and resulted in the infamous “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey. While this was taking place, three renegade bishops set up the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” with support from the Turkish government that sought to undermine the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

1923

As we begin 1923, just by way of reminder: Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow was under house arrest, and while the famine in Russia was receding somewhat, people were still starving. In Syria, the French were in the process of carving up the territory of the Patriarchate of Antioch into separate countries. The British had control over the finances of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and were working to set up a Jewish state, while the Patriarchate, in dire financial straits, was selling off property to Jewish settlers. The various Orthodox ethnic groups in America experienced internal schisms, and countless lawsuits over church property were underway. That’s just a fraction of what was going on when 1923 began, but since I’m not going to mention, say, Antioch or Jerusalem in this section, don’t forget that everything was a mess there, too.

On January 4, 1923, the Turkish delegation to the Lausanne Peace Conference formally demanded that the Ecumenical Patriarchate be removed from Turkey – preferably to Mount Athos. The other delegates proposed a compromise, whereby the Ecumenical Patriarch could remain in Constantinople but would be stripped of all political and administrative authority. Venizelos, acting as the leader of the Greek delegation, even offered to sacrifice his friend Patriarch Meletios, proposing that Meletios – an enemy of the Turks – would resign if the Patriarchate were allowed to remain in Turkey. The Turks agreed to the deal.

Then, on January 30, Greece and Turkey agreed to a “population exchange,” under which most of the Muslims in Greece would be deported to Turkey, and most of the Greeks in Turkey would be deported to Greece. Some two million people were deported, including about 1.5 million Greek Orthodox Christians living in Turkey.

In February, by now sort of a dead man walking, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios invited all of the Orthodox Churches to a meeting in Constantinople, mainly to consider revisions to the church calendar, as well as remarriage of clergy.

Also in February, an archimandrite, reportedly acting out of loyalty to the Church of Russia, assassinated the Polish primate, Metropolitan George. (I should stress, nobody accused Patriarch Tikhon or the Russian Church of being involved in the murder; the archimandrite-assassin seems to have been acting on his own.) Here’s an account of the murder, from the New York Times on February 10, 1923: “[Archimandrite] Smaragd, a former rector of the Russian Seminary at Chelm, a short time ago was suspended and sent to a small parish in Volhynia. He arrived in Warsaw yesterday and made an appointment to see the Metropolitan at 6 o’clock. After an hour’s conversation servants heard three shots, and when they rushed in found the Metropolitan dead. The monk did not resist arrest.”

In March, a delegation from the new Albanian Orthodox Church arrived in Constantinople to meet with Patriarch Meletios. It expected to receive formal recognition of Albanian autocephaly, but the Ecumenical Patriarch only acknowledged partial autonomy.

Also in March, in Russia, Vladimir Lenin suffered his third stroke and lost the ability to speak.

In April, the first Renovationist Council began in Moscow. This “Council,” which ended in early May, purported to depose Patriarch Tikhon, and it instituted a series of major church reforms, including allowing married bishops, remarriage of clergy, and marriage of monastics.

While this was taking place, on May 1, the forced “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey formally took effect. Thousands upon thousands of Orthodox Christians were forced to abandon their homelands.

Just days after this, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios convened the landmark “Pan-Orthodox Congress,” which ended in June with the adoption of the “Revised Julian Calendar.” On June 1, Meletios was attacked by a mob connected with the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” who dragged him down a flight of stairs, tore at his robes, and demanded that he resign. He shouted back, “Let them hang me if they will, but now I shall not retire!” An Allied police force in Constantinople intervened and saved Meletios, who very well could have been killed otherwise.

Besides the calendar, the other big topic at the Pan-Orthodox Congress was the remarriage of widowed clergy. The Congress decided to maintain the tradition of the Church in prohibiting clergy remarriage, but to allow such remarriages in exceptional cases, “making provision for the terrible position of widowed clergy at the present time,” i.e., in the wake of World War I. A final determination was referred to a future ecumenical council. The Russian Metropolitan Anastasii, future head of ROCOR, opposed the decision, arguing against what he viewed as a dangerous exercise of oikonomia.

Just after the Pan-Orthodox Congress ended, Patriarch Tikhon was set free from house arrest. He initially announced that the Russian Orthodox Church would adopt the calendar reforms of the Congress, although the Russian Orthodox people mostly rejected this, and in the end, the Russian Church retained the Old Calendar.

The next month – July – Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios separately received the Churches of Finland and Estonia – which had previously been part of the Russian Orthodox Church – under the jurisdiction of Constantinople. These would be Meletios’ final acts as Ecumenical Patriarch: within days, under pressure from the new leaders in Turkey, Meletios left the country on a British steamship bound for Mount Athos.

Also in July, the first “Arab Orthodox Congress” of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem was held in Haifa, briefly raising hopes that Jerusalem – like Antioch before it – might be able to throw off the oppressive control of the ethnically Greek Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre and elect a Patriarch from the native population. Unfortunately for the native Orthodox Christians, this effort ultimately stalled out.

In September, Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow issued an ukaz naming Metropolitan Platon as temporary head of the Russian Archdiocese of North America. This confirmed the previous year’s acts of the Russian Holy Synod and the All-American Sobor.

In October, the Republic of Turkey was created. On October 2, literally as the Allied evacuation of Constantinople was taking place, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was meeting at the Phanar. Papa Efthim, leader of the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” burst into the room with a guard of Turkish police. He ordered the Holy Synod to declare Patriarch Meletios to be deposed within ten minutes. The Holy Synod complied. Then the Turkish police expelled six of the eight Holy Synod members, along with the Locum Tenens, from the building. (All of the expelled bishops had sees outside of Turkey.) Papa Efthim then replaced the seven expelled bishops with his own partisans. At that moment, it appeared that the Ecumenical Patriarchate either no longer existed, or had just been taken over by a coup d’etat.

Meanwhile, Patriarch Meletios was in Greece, and was thinking about moving the Ecumenical Patriarchate to Thessaloniki. Both the Greek government and the Church of Greece opposed this, and they finally convinced Meletios to resign as Patriarch. He signed a document backdated to September 20, after obtaining assurances from Turkey that they would open the path for a new patriarchal election, not controlled by Papa Efthim and the “Turkish Orthodox Church.” (By backdating the abdication, Meletios was attempting to undercut the actions of Papa Efthim on October 2.)

On October 6, the Turkish government issued a decree requiring any candidate for a religious election in Turkey (read: Ecumenical Patriarch) must be a Turkish citizen, and must be present in Turkey during the election process.

Also in October, the New Calendar took effect in the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

In November, the former priest John Kedrovsky, now a “bishop” of the Soviet-backed Living Church, arrived in New York and attempted to take control of St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral. This was one of the early battles in a three-decade-long war over church properties between the Russian Metropolia (today’s OCA) and pro-Soviet religious authorities.

It was a difficult month for the Russian Orthodox abroad – the same month, a decree was issued under Patriarch Tikhon’s name, condemning ROCOR as a non-canonical body. But at the same time, another decree from the Patriarch confirmed the legitimacy of Metropolitan Evlogy’s exile jurisdiction in Western Europe. This was the beginning of the split of the Western Europe jurisdiction from ROCOR.

In Russia itself, Communist leaders held a shocking event in a Moscow opera house – an infant girl was brought by her parents to a red-draped “altar” and “christened” into Communism by Nikolai Bukharin, editor-in-chief of Pravda and a major Bolshevik figure. Four thousand people watched and cheered.

Meanwhile, in Greece on November 10, the holy hieromonk St. Arsenios the Cappadocian died, just a few months after leading his congregation from Cappadocia to Corfu as part of the forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey. One of his parishioners was an infant who grew up to be St. Paisios the Athonite, one of the greatest saints of our time.

Also in November, Pope Pius XI issued a papal encyclical, calling on the Orthodox Churches to submit to the authority of the Pope.

In December, the Holy Synod of Constantinople elected Gregory VII as Patriarch. Papa Efthim and his supporters again mobbed the Phanar and took control of the building. But this time, the Turks weren’t on his side – Turkish authorities expelled Papa Efthim and declared their acceptance of the election of Patriarch Gregory.

1924

In Poland, between 1918 and 1924, some 400 Orthodox churches were confiscated by the Polish government, and others were destroyed. Among these, the Polish Orthodox Christians lost St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in Warsaw and the important Suprasl Monastery. As 1924 began, Gregory VII had just been elected Patriarch of Constantinople but entered the role with the Patriarchate in a precarious state. The mass deportation of Greeks from Turkey was underway, and the Church of Russia suffered from the dual threats of Soviet persecution and the Living Church schism. Antioch’s territory was being partitioned by the French, and the British-controlled Jerusalem Patriarchate was selling off land to Jewish settlers.

In January 1924, Vladimir Lenin died. Stalin arranged for Lenin’s body to be embalmed and put on display in a mausoleum, in a disgusting imitation of incorrupt saints of the Orthodox Church that the Communists were hell-bent on destroying.

Also in January, an ukaz was issued under the name of Patriarch Tikhon, removing Metropolitan Platon from his leadership of the Russian Archdiocese of North America for “public acts of counter-revolution.” Platon and his Archdiocese ignored this order.

In March, the Church of Greece adopted the New Calendar.

In early June, Patriarch Tikhon received a letter from Archimandrite Basil Dimopoulos, the official representative of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Russia and an ardent supporter of the Living Church schism. Dimopoulos told the great Tikhon to “yield and immediately depart from the government of the Church,” and, furthermore, that “the patriarchate should be eliminated, at least temporarily.” Patriarch Tikhon declined to follow Dimopoulos’ instructions.

The same month, supporters of Albanian primate Metropolitan Fan Noli (who was also a prominent political leader) overthrew the pro-Muslim government of King Zog of Albania, and Noli himself became prime minister and regent. This arrangement lasted until December, when the king’s forces re-entered the country, taking control of the capital on Christmas Eve. Noli fled Albania, eventually ending up in America and leading an Albanian diocese in the United States.

Also in June, the Antiochian Archdiocese of North America was officially created, concluding the work of the patriarchal delegation that had come to America in 1922.

In late August, the Patriarch of Serbia, Dimitrije, who had already been enthroned as patriarch in Belgrade, was enthroned in the ancient see of Peć, thereby reinstituting the patriarchal see that had been abolished in 1766.

In November, the Ecumenical Patriarchate issued a Tomos of Autocephaly to the Polish Orthodox Church. Just days later, Patriarch Gregory VII of Constantinople died of a massive heart attack. He had been Ecumenical Patriarch eleven months, and was succeeded by Patriarch Constantine IV.

Also in November, the Church of Romania adopted the New Calendar.

In December, Patriarch Tikhon was attacked in his home. His assistant, Yakov Polusov, stepped in front of Tikhon to defend him, and was shot dead. Immediately after this, knowing that his days were numbered, Tikhon made a “will” in which he designated three possible successors – not a strictly canonical thing to do, but then, the Russian Church wasn’t exactly in a position to follow canonically normative procedures.

1925

By 1925, following his near-assassination, Patriarch Tikhon’s health was in serious decline. Among other things, his heart was failing, and he suffered from severe inflammation of the mouth.

In December 1924, the Ecumenical Patriarchate was about to elect a new Patriarch. The top contender was Metropolitan Constantine of Dercos. This was a problem, because Constantine had only moved to Istanbul in 1921, which was after the October 1918 deadline set by the Lausanne Treaty – all Greeks who were residents of Istanbul in October 1918 were exempt from deportation, but any who arrived later could be deported. The Turks briefly arrested Constantine and two other candidates, and the Greek consul in Istanbul begged the Holy Synod to postpone the election. But they refused, and the next day, Constantine was elected Ecumenical Patriarch. The Turks insisted that Constantine was still going to be deported.

An international “mixed commission” had been set up to oversee implementation of the Lausanne Treaty, and the Greek representatives tried to appeal to this commission on behalf of the Patriarch. But the commission’s hands were tied – the deportation provisions of the Lausanne Treaty made no exceptions for church leaders, so the Patriarch was to be treated no differently than any other Greek.

At around midnight on January 30, 1925, the Ankara-based Turkish government sent a cipher telegram to Istanbul, ordering the expulsion of Patriarch Constantine from the country. At 6:30 in the morning, the Patriarch was confronted by the Assistant Director of Police, who took him to a railroad station and put him on a train to Greece. Rumors swirled that more Orthodox bishops would be deported in the coming days. Greece responded by severing diplomatic ties with Turkey and appealing to the League of Nations.

Constantine had been Ecumenical Patriarch for about two months when he was deported, and it was not at all clear, at the time, whether Turkey would allow for the election of a new patriarch. The Archbishop of Athens was indignant – he said that the Patriarch’s expulsion was “much more serious than even the hanging of Patriarch Gregory V in 1821, because its object is not only to terrify the Greeks, but to accomplish a plan for uprooting the Patriarchate.”

The Turks and the Greeks and the remaining Holy Synod members in Istanbul were negotiating next steps, but then the exiled Patriarch Constantine threw a monkey wrench in March when he refused to abdicate. Both Constantine and his predecessor Meletios, along with a sizeable number of metropolitans, proposed transferring the Patriarchate to Mount Athos and appointing an archbishop to the Phanar in Istanbul.

But, counterintuitively, the Turks weren’t all-in on expelling the Patriarchate itself. The British ambassador to Turkey explained, “It has been realised that its continuance here may provide Turkish policy with certain levers which could be lost if the institution was completely suppressed. The present intention of Angora [Ankara] is, therefore, to keep the Patriarchate here, but in such a reduced state that it would be a mockery of its former self and a ready tool in Turkish hands.” This is the Turkish position that ultimately won out, and the Ecumenical Patriarchate has remained in Istanbul to this day.

Amidst this uncertainty, in February, the Holy Synod of the Romanian Orthodox Church decided to elevate their Church to the rank of Patriarchate. Later in the year, Metropolitan Miron was enthroned as the first Patriarch of Romania.

Over in Russia, Patriarch Tikhon underwent an operation on his mouth. His physical condition continued to worsen until, in early April, the great, long-suffering Patriarch Tikhon died. He was only sixty years old. At the time of St. Tikhon’s death, Metropolitan Peter of Krutitsy was the only one of the three designated successors in St. Tikhon’s will who wasn’t in prison or exile, so he took the position of Patriarchal Locum Tenens. Three days after St. Tikhon’s death, a purported “last will and testament” of the Patriarch was published in Soviet newspapers, caving to Soviet pressure on a variety of fronts.

Then in May, under heavy pressure from the Greek government, Ecumenical Patriarch Constantine resigned. In July, Basil III was elected Ecumenical Patriarch, this time with Turkish permission. The same month, the Moscow locum tenens Metropolitan Peter issued a letter reiterating the Orthodox rejection of the renovationist Living Church.

Also in July, Metropolitan Platon, leader of the Russian Metropolia in America (today’s OCA), was forcibly removed from his cathedral by police officers, who were enforcing a court order to hand over the cathedral to the pro-Soviet Bishop Adam Philipovsky. But three weeks later, the tables turned – a new court order awarded the cathedral to Metropolitan Platon, and police entered the building and ousted Bishop Adam. This was only a small episode in the back-and-forth legal (and sometimes physical) battles over St. Nicholas Cathedral.

On August 23, the Syrian Druze leader Sultan Pasha al-Atrash declared a revolution against France. The Great Syrian Revolt lasted for two years, and Orthodox Christians participated in the multi-religious uprising.

In October, with the canonical Russian Orthodox Church still under heavy persecution by the state, the second Renovationist Council of the “Living Church” convened in Moscow. The council’s honored guest was Archimandrite Basil Dimopoulos, official representative of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Dimopoulos and a representative of the Patriarchate of Alexandria concelebrated the divine liturgy with the Renovationists.

In November, the Soviet media published accusations against Metropolitan Peter. Over the next month, numerous Orthodox bishops were arrested, including, on December 10, Metropolitan Peter himself. Like St. Tikhon before him, Metropolitan Peter had designated successors in the event of his arrest, and according to his instructions, leadership of the Russian Church passed to Metropolitan Sergius of Nizhny Novgorod. A group of ten bishops rejected Sergius’ authority and immediately held their own council, electing Archbishop Gregory of Ekaterinburg as their leader. The Church of Russia, already facing heavy persecution and dealing with the Living Church schism/heresy, now faced its own internal schism, as well.

Epilogue

From 1917 to 1927, the Greek Orthodox population of Istanbul fell by 75%, from 400,000 to 100,000. From his ascendance in 1923 through the end of World War II, Ataturk’s government worked to push religion out of public life, and the embattled Ecumenical Patriarchate basically took it without a fight. This state of affairs lasted until the beginning of the Cold War, when the United States government began to actively use the Ecumenical Patriarchate as a tool against the Soviet Union.

Way back in 1912-13, in the Balkan Wars, Greece had acquired new territories in the north, known, conveniently, as the “New Territories” (or, sometimes, the “New Lands”). These New Lands remained the territory of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and weren’t absorbed into the Church of Greece, but from a practical standpoint, it was getting harder and harder for Constantinople to actually administer them. In 1928, after two years of negotiations with the Greek government, the Ecumenical Patriarchate issued a Patriarchal and Synodical Act, the upshot of which was that the New Lands would remain, officially, part of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, but the bishops for these territories would be chosen by the Church of Greece and confirmed by Constantinople. This procedure remains in effect today, with a total of 35 bishops overseeing the New Lands under these terms.

In 1926, Meletios Metaxakis, erstwhile Patriarch of Constantinople, was elected Patriarch of Alexandria, a position he held until his death in 1935. Although Meletios is usually associated with the Ecumenical Patriarchate, he actually served as Patriarch of Alexandria for much longer – 9 years in Alexandria compared to about a year and a half in Constantinople. During his tenure in Alexandria, Meletios received a trio of Ugandan men and ordained them priests, kick-starting the growth of Orthodoxy in sub-Saharan Africa.

The Royalist-Venizelist division in Greece continued into the 1930s. Venizelos himself returned to power from 1928-32, and the signature achievement of this last hurrah was a 1930 treaty with Turkey, ending years of conflict. But Venizelos’ party was defeated in elections in 1932, was nearly assassinated in 1933, and died in Paris in 1936, one year after the death of his old ally, Patriarch Meletios.

Cyprus, which had been annexed by the British Empire in 1914, became a British Crown Colony in 1925. Unhappy with their British overlords, Greek Cypriot nationalists – led by two Orthodox bishops – revolted in 1931. The British crushed the revolt and exiled both bishops, along with a third bishop who had gone to London to plead his people’s case. This left just two bishops in the entire Church of Cyprus – and then, in 1933, the Archbishop died, leaving Metropolitan Leontios of Paphos as the sole hierarch on the island. One bishop is obviously far short of a quorum to elect a new Archbishop, so Leontios asked the British to allow the other Cypriot hierarchs back onto the island. The British refused and suggested that perhaps the Ecumenical Patriarch could simply appoint a new Archbishop. Had this happened, Cyprus’ ancient autocephaly would have effectively been abolished. But Leontios wouldn’t agree to it, and he held down the fort as locum tenens for the next 14 years.

The new Moscow locum tenens, Metropolitan Sergius, was arrested and imprisoned for several months in 1926-27. After his release, in an attempt to placate the Soviets, Sergius issued his now-infamous declaration of loyalty, proclaiming that, for the Russian Church, the Soviet Union is “our civil motherland, whose joys and successes are our joys and successes and whose failures, failures.” He also condemned bishops and priests who criticized the Soviet regime. This capitulation to a hostile anti-Christian power became a line in the sand for many Russian Orthodox Christians, and in many ROCOR circles it came to be referred to as the “heresy of Sergianism.” Defenders of Sergius point out that his declaration of loyalty was an unfortunate necessity to protect the Russian Church from further Soviet aggression. Sergius remains one of the most divisive figures in modern Orthodox history.

The Living Church appeared to be ascendant in late 1925, having just held its second council and concelebrated with representatives from Constantinople and Alexandria. But this turned out to be the high-water mark for the Renovationists – thanks in part to Metropolitan Sergius’ declaration of loyalty, the Living Church was no longer particularly useful for the Soviets, and it declined into nothingness in the years to come. Many of its adherents repented and returned to canonical Orthodoxy.

The other Russian schismatic group, the “Gregorians” (named for their leader, Archbishop Gregory of Ekaterinburg), came and went even sooner. They failed to gain much traction after declaring their independence from the Russian Church in December 1925, and for all intents and purposes they were finished by 1927 (although they still existed in some form for another decade).

The Russian Orthodox Church continued to suffer persecution, although the open brutality of the 1917-25 period gave way to the gulags and a general spirit of repression. During World War II, in an effort to shore up support throughout the country, Stalin allowed the election of Sergius as Patriarch of Moscow.

The Georgian Orthodox Church, which had briefly attempted to restore its autocephaly in 1917 only to have it crushed by the Soviets in 1921, suffered particular persecution under the Stalinist Soviet government. Stalin – who was himself born in Georgia – saved some of his most brutal treatment for the people of his own homeland. From 1928 to 1939, the number of priests in the Church of Georgia fell from 1,110 to just 83. But, as with the Moscow Patriarchate, the Church of Georgia benefitted from relatively greater freedom during World War II, and in 1943, the Georgia’s ancient autocephaly was restored under Stalin’s orders.

The Great Syrian Revolt continued through 1927, but in the end, the French won out. Syrian farms and villages were devastated and 100,000 homeless Syrians descended upon Damascus. The Church of Antioch was divided into two factions: one was Beirut-based and pro-Western, with French backing; the other was Damascus-based, pro-Russian, and supported by Arab nationalists. In 1928, Patriarch Gregory of Antioch died, sparking a succession crisis. The two factions each claimed legitimacy and elected their own Patriarch, and for a brief period, two men claimed the title “Patriarch of Antioch.” In January 1933, the Beirut faction’s leader died, leaving Damascus’ Patriarch Alexander III as the sole Patriarch. Despite this, the factionalism within the Patriarchate of Antioch continued for decades to come.

Orthodoxy survived the chaos of 1917-1925 — after all, it is the Church, against which the Lord promised that “the gates of hell shall not prevail.” But the Body of Christ on earth came out of this period bruised and battered. The empires that had provided a structural framework for centuries were suddenly no more. The epoch that followed 1925 — our epoch — represents a new order in world Orthodoxy: an order that remains in considerable flux to this day.

Selected References

Matthew Spinka, “Post-War Eastern Orthodox Churches,” Church History 4:2 (June 1935), 193-122.

Dimitry V. Pospielovsky, A History of Soviet Atheism in Theory, and Practice, and the Believer, vol. 2: Soviet Anti-Religious Campaigns and Persecutions, St Martin’s Press, New York (1988).

Antoni Mironowicz, “The Destruction and Transfer of Orthodox Church Property in Poland, 1919-1939,” Polish Political Science Yearbook Vol. XLIII (2014), 405-420.

Konstantinos Papastathis, “Constantinople and Jerusalem: the Delegation of Bishop Anthimos in the Holy Land, 1921,” Revue d’Historie de l’Universite de Balamand 15 (Jan. 2007).

Konstantinos Papastathis, “Church Finances in the Colonial Age: The Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem under British Control, 1921-25,” Middle Eastern Studies 49:5 (2013), 712-731.

Konstantinos Papastathis and Ruth Kark, “The Politics of church land administration: the Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem in late Ottoman and Mandatory Palestine, 1875-1948,” Byzantine and Modern Greek Studies 40:2 (2016), 264-282.

Konstantinos Papastathis, “Greece in the Holy Land during the British Mandate: Diplomacy and Religion,” Jerusalem Quarterly 71 (2017), 30-42.

Itamar Katz and Ruth Kark, “The Church and Landed Property: The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem,” Middle Eastern Studies 43:3 (May 2007), 383-408.

Bedross Der Matossian, “Administering the Non-Muslims and ‘The Question of Jerusalem’ after the Young Turk Revolution” in Eyal Ginio and Yuval Ben-Bassat, eds., Late Ottoman Palestine: The Period of Young Turk Rule (London: I.B. Tauris, 2011), 211-239.

P.J. Vatikiotis, “The Greek Orthodox Patriarchate of Jerusalem between Hellenism and Arabism,” Middle Eastern Studies 30:4 (Oct. 1994), 916-929.

Anna Dickinson, “Quantifying Religious Oppression: Russian Orthodox Church Closures and Repression of Priests 1917-41,” Religion, State and Society 28:4 (2000), 327-335.

Theodora Dragostinova, “Nationalizing the Greeks of Bulgaria, 1900-1939,” Slavic Review 67:1 (Spring 2008), 154-181.

Stelios Nestor, “Greek Macedonia and the Convention of Neuilly (1919),” Balkan Studies 3:1 (1962), 169-184.

Patrick Viscuso, A Quest for Reform of the Orthodox Church: The 1923 Pan-Orthodox Congress (Berkeley, CA: InterOrthodox Press, 2006).

Mira Radojevic and Srdan Micic, “Serbian Orthodox cooperation and frictions with Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and Bulgarian Exarchate during interwar period,” in Bisar Georgiev, et al, eds., Studia Academica Sumenensia: Christianity in Southeastern Europe Vol. 2 (The University of Shumen Press, 2015).

Daniel Shubin, A History of Russian Christianity, Vol. IV: The Orthodox Church 1894 to 1990 (New York: Algora Publishing, 2006).

Rym Ghazal, “Lebanon’s dark days of hunger: The Great Famine of 1915-18,” The National (April 14, 2015), https://www.thenational.ae/world/lebanon-s-dark-days-of-hunger-the-great-famine-of-1915-18-1.70379.

Daniela Kalkandjieva, The Russian Orthodox Church, 1917-1948: From Decline to Resurrection, Routledge, 2014.

Stamatopoulos Dimitrios, “Greek-Orthodox Patriarchate of Constantinople, 1839-1923”,

Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople, http://constantinople.ehw.gr/forms/fLemmaBodyExtended.aspx?lemmaID=11472 (accessed on March 14, 2019).

Elcin Macar, “Greek-Orthodox Patriarchate of Constantinople, 1923-today,” Cultural Portal of the Aegean Archipelago, http://constantinople.ehw.gr/forms/fLemma.aspx?lemmaId=11470 (accessed on March 14, 2019).

Harry J. Psomiades, “The Ecumenical Patriarchate Under the Turkish Republic: The First Ten Years,” Balkan Studies 11 (1961), 47-70.

Alexis P. Alexandris, “The Expulsion of Constantine VI: The Ecumenical Patriarchate and Greek-Turkish Relations, 1924-1925,” Balkan Studies (1981), 333-363.

Fr. Nikolaj L. Kostur, The Relationship of the Serbian Orthodox Church to the ROCOR: 1920-1941, B.Th. thesis from Holy Trinity Seminary, Jordanville, NY (2005), published at http://www.rocorstudies.org/2018/08/12/the-relationship-of-the-serbian-orthodox-church-to-the-rocor-1920-1941/ (accessed on September 20, 2019).

Emmanouil G. Chalkiadakis, “The Patriarch of Alexandria Meletios Metaxakis and the Greek-Orthodox migration and mission in Africa,” paper presented at the joint American Society of Church History / Ecclesiastical History Society Conference Migration and Mission in Christian History, Oxford, 3-5 April 2014.

Leave a Reply