In 1908, a Roman Catholic priest and writer, Adrian Fortescue, published his landmark book The Orthodox Eastern Church, presenting Orthodoxy to the English-speaking world through the eyes of a very well-informed but also very papist Roman Catholic from England. In one section of the book, Fortescue surveys the Orthodox world, telling the recent history and then-current situation in each of the world’s autocephalous churches. We’ve already published Fortescue’s accounts of the Pentarchy and Cyprus and the Church of Russia. Today, we’re moving on to the Church of Greece. As we saw last time, Fortescue is hardly an impartial observer — his contempt for Orthodoxy, and Russia in particular, comes through clearly in his writing. The full text of Fortescue’s book is available for free at The Internet Archive.

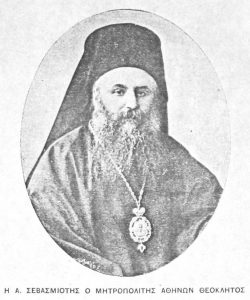

Archbishop Theoklitos of Athens was primate of the Church of Greece from 1902-17 and again from 1920-22.

The Greek Church (1850)

The established Church of the modern kingdom of Greece is the only body that ever describes itself, or can in any way correctly be described, as the “Greek Church.” It is the oldest of the national Churches that in quite modern times have been cut away from the Byzantine Patriarchate, and it was born in the throes of one of the greatest of the many domestic quarrels of the Orthodox. As soon as there was any beginning of a Greek Government during the War of Independence the Greeks declared their Church free from the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Phanar had so long identified its policy with that of the Porte that the men who were fighting the Sultan would acknowledge no sort of dependence on the Patriarch. The first Greek National Assemblies in 1822 and 1827 declared that the Orthodox faith is the religion of Greece, and pointedly said nothing about the Ecumenical Patriarch.

In July, 1833, the Greek Parliament at Nauplion formally declared the National Church autocephalous, and set up a Holy Directing Synod to govern it, in exact imitation of Russia. The Head of the Church of Greece is Christ, its governor in external affairs the king. The same Parliament then proceeded to suppress most of the monasteries. In 1844 the same law was repeated: ” The Orthodox Church of Hellas acknowledges our Lord Jesus Christ as its Head. It is inseparably joined in faith with the Church of Constantinople and with every other Christian Church of the same profession, but is autocephalous, exercises its sovereign rights independently of every other Church, and is governed by the members of its Holy Synod.” Copies of these laws were duly sent to Constantinople and to all the other Orthodox Churches. Naturally the Ecumenical Patriarch was indignant that his subjects should so coolly throw off his authority without, having even consulted him. So he first refused to acknowledge the Greek Holy Synod at all. Among the Greeks, too, a large party resented the whole uncanonical proceeding.

In 1849 the Greek Government, anxious to get the Patriarch’s consent to what it had done, sent him the Order of St. Saviour that it had just founded, and a friendly message from the “Church of Hellas.” The Patriarch (Anthimos IV, 1840-1841, 1848-1852) took the Order, and then said he knew nothing about a Church of Hellas. However, Russia and the other Orthodox Churches, always willing to humble the Phanar, acknowledged this new sister and insisted on his doing so too. So in 1850 Anthimos held a synod which published the famous Tomos (decree). The Tomos did recognize the Greek Church as autocephalous, but, still anxious to assert some sort of authority over it, prescribed the way in which it must be constituted. It especially forbade any interference of the State in Church affairs and added an amusing tirade against Erastianism. It also insisted that the Patriarch should be named in the Holy Liturgy throughout Greece, that the Holy Chrism should be sent from Constantinople, and that the synod should submit all important questions to the Patriarch. (This is just the case of the causce maiores that among Catholics have to go to Rome. It is very curious how the Ecumenical Patriarch always tries (though quite futilely) to be a Pope.)

This Tomos excited great indignation among the nationalist Greek party. They had determined to have nothing more to do with the Phanar at all. Theoklitos Pharmakides, their chief leader, wrote an angry refutation: “The Synodical Tomos, or concerning Truth,” and the only suggestions they would accept from the Tomos were that the Metropolitan of Athens should be ex-officio president of the Holy Synod, and that the chrism should be supplied by the Patriarch. After a great deal more quarrelling, at last the Phanar had to submit and to acknowledge one more sister in Christ, the Greek Holy Synod. Since then there has been no more question about the autonomy of the Church of Hellas, and in face of the common Slav danger, the Free Greeks and the Phanar have now forgotten their differences and have become firm allies.

Since its original constitution the Greek Church has received two additions. In 1866 England ceded the Ionian Isles to Greece, and at once the Greek Government separated the dioceses of those islands from the Patriarchate and joined them to its own Church. Again the Phanar protested, and there was a rather angry correspondence between Constantinople and Athens, but by now the principle that political independence and political union must be exactly reflected in the Church was becoming more and more openly recognized by the Orthodox. So this union was made without much trouble. In 1881 Thessaly and part of Epirus were added to Greece, and again the ten dioceses of these lands were joined to the Greek Church. This time the Phanar did not even protest.

***

The Church of Hellas has now thirty-two sees, of which the first is that of Athens. At present in Greece, as in most Orthodox lands, the majority of these bishops bear the quite meaningless title of Metropolitan, but the Holy Synod has decreed that as the present metropolitans die their successors shall be called simply Bishops, and that the only see with the Metropolitan title in future shall be Athens. There are to be no provinces nor graduated jurisdiction, all bishops shall be immediately and equally subject to the Holy Synod. Of that synod my Lord of Athens is president, four other bishops are chosen by rote to be members for one year, the Royal Commissioner must be present at every session, and without his signature no decree is valid. The Greek Holy Synod, then, is an exact copy of the Russian one, and under it the Greek Church is just as Erastian as the Church of Russia, with, however, this exception, that, instead of being at the mercy of an autocrat, it has to submit to the even worse rule of a Balkan Parliament.

In spite of this, however, the little Greek Church is as orderly and well organized as any of the Orthodox Communion. Its bishops and clergy are reasonably well paid by the State, so they have not the disadvantage of grinding poverty, and the University of Athens has a theological faculty quite well equipped for their education. The two most important theologians of this Church have been Theoklitos Pharmakides (+1860), who was the leader of the Liberal school, friendly to Protestants, anxious for practical reforms in the Church, for free discussion and higher Bible criticism, advocating more education and fewer monks, and his opponent Oikonomos (+1857), who had been educated in Russia and the East and was a rigid conservative, valuing the Septuagint above new translations from the Hebrew, more diligent in the study of the Fathers of the Church than curious about the Tubingen theories, rather fearful of losing the old Orthodox faith than anxious for new reforms. He was also a famous orator and preached the sermon over the body of the martyr-Patriarch Gregory V at Odessa, that is by far the finest piece of modern Greek oratory. But he thought that the Septuagint is inspired, and believed in Pseudo-Dionysius.

The Greek Church has vindicated its right as a living Christian body by producing a fair proportion of heretics. Theophilos Kaires, a priest, left the Orthodox Church and founded a new religion which he called “God-worship,” and which is a sort of Deism on the lines of the Encyclopaedists, varied by the fact that its prayers are said in Doric Greek. He was excommunicated, of course, and considerably persecuted till he died in prison in 1853. Laskaratos founded a form of Presbyterian Protestantism; Papadramantopoulos a Positivist sect; Plato Drakulis revived the wildest Gnostic theories. At present the enormous influence of Western, and especially French, ideas, which accompanies the feverish anxiety of the Greeks to be a European people, produces, besides most quarrelsome politics and a vast debt, a strong tendency towards free-thinking and scorn of their Church among the young men who dress in French clothes and smoke very bad cigarettes in the cafes at Athens.