In 1908, a Roman Catholic priest and writer, Adrian Fortescue, published his landmark book The Orthodox Eastern Church, presenting Orthodoxy to the English-speaking world through the eyes of a very well-informed but also very papist Roman Catholic from England. In one section of the book, Fortescue surveys the Orthodox world, telling the recent history and then-current situation in each of the world’s autocephalous churches. Previously, we published sections on the ancient Pentarchy, the Church of Russia, and the Church of Greece. Today, we’re moving on to two very ancient churches — Georgia and Sinai — whose status changed a lot over the centuries, and has changed even more since Fortescue wrote about them: Georgia and Mount Sinai.

As we’ve already seen, Fortescue is hardly an impartial observer — his contempt for Orthodoxy, and Russia in particular, comes through clearly in his writing. Nonetheless, his accounts provide a valuable record of a critical non-Orthodox perspective on the Orthodox Church at the turn of the 20th century. The full text of Fortescue’s book is available for free at The Internet Archive.

The Church of Sinai

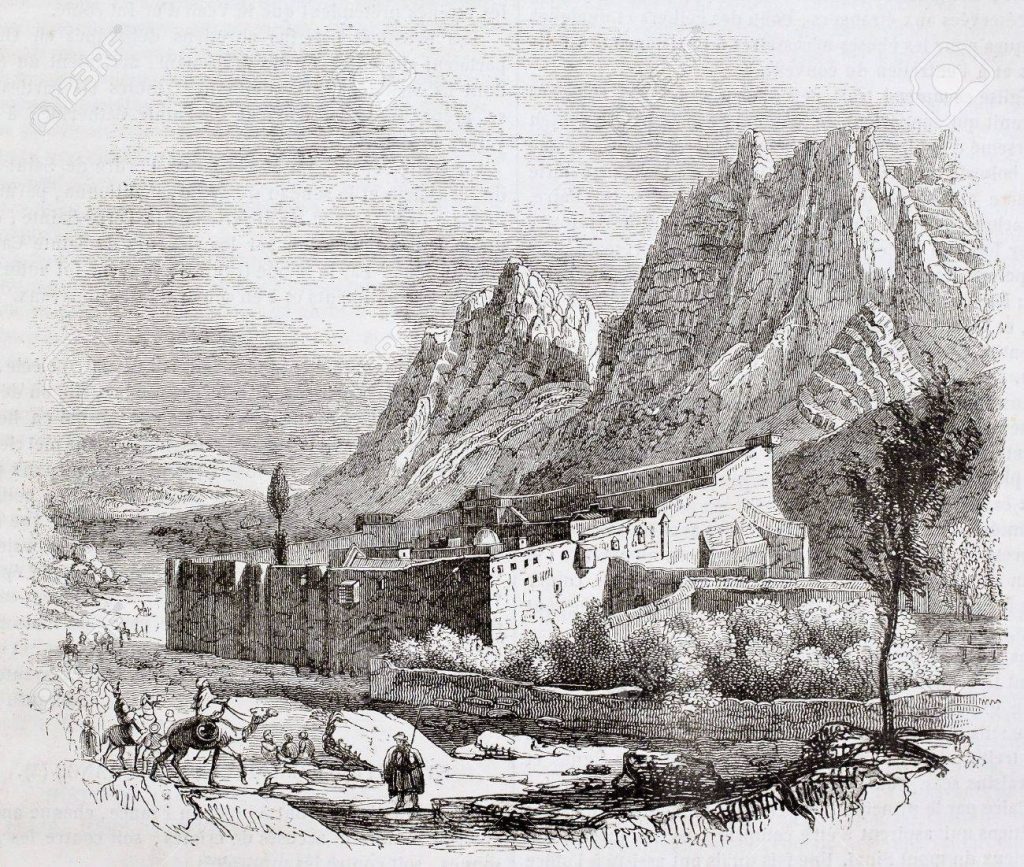

One of the chief shrines to which the Orthodox for many centuries have gone in pilgrimage is Mount Sinai, the “mountain trod by God.” On this mountain stands the great monastery of St. Katharine. It became very rich, and has metochia (daughter-houses) at Cairo, Constantinople, Kiev, Tiflis, and all over the Orthodox world (fourteen altogether). Since the 10th century the Abbot (Hegoumenos) of Mount Sinai has joined to his office the diocese of Pharan in Egypt, has always been consecrated bishop, and has borne the title of Archbishop of Mount Sinai. He has always been and still is ordained by the Patriarch of Jerusalem, and formerly he obeyed that patriarch’s jurisdiction. However, chiefly because of the distance of his monastery from the Holy City, he succeeded after a great struggle in being recognized as independent of any superior authority. In 1782 this position was officially acknowledged by the patriarchs; and so the Archbishop of Sinai rules over the smallest of the Orthodox Churches, having himself no superior but Christ and the seven councils. Since, however, he is ordained at Jerusalem, and since the Orthodox are always disposed to consider that the right of ordaining involves some kind of jurisdiction, the Patriarchs of Jerusalem have continually tried to reassert their old authority over him and his monastery.

The last dispute was in 1866. In that year the Archbishop-Abbot, Cyril Byzantios, had a great quarrel with his monks. Unable to manage them alone and unwilling to appeal to Jerusalem, lest that should seem an acknowledgement of dependence from that see, he sent to Constantinople to ask the Ecumenical Patriarch to help him keep his monks in order. Of course the Phanar was delighted to have an excuse for asserting some sort of authority over another Church, so the Patriarch (Sophronios III, 1863-1866) wrote back that he would gladly support his brother of the God-trodden mountain. Then the Patriarch of Jerusalem (also named Cyril) heard of what had happened and summoned a synod in 1867, which declared that the Great Church had no authority to interfere in anything that happened outside its own patriarchate, and that if there was any trouble on Mount Sinai the proper person to put things right was the Patriarch of Jerusalem.

“If we acted otherwise,” declared this synod, “people would think that we tolerate such anti-canonical interference, and that we acknowledge foreign and unknown authorities in the Church as well as the only lawful and competent high jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Synods.” Cyril of Jerusalem sent the Acts of his council to all the other autocephalous Churches, and once more they all rose up against the usurpation of the Phanar. He also deposed Cyril Byzantios for what he had done and, although Sophronios of Constantinople stood by him, the feeling against them both was so strong throughout the Orthodox world that Byzantios had to submit to his deposition and Sophronios had to resign.

However, Mount Sinai is recognized as an independent Church, and stands with its one bishop and handful of monks on just the same plane as the enormous Russian Church. Its archbishop lives at the Sinaitic metochion at Cairo; he rules over only the monastery and its fourteen metochia, and his authority is very much limited by the council of monks, who share the government. The present archbishop is Lord Porphyrios Logothetes, who was formerly the Orthodox priest in Paris. His Beatitude has brought from the land of the Latins a great dislike for their Church, and when he was consecrated at Jerusalem on October 30, 1904, he took the opportunity of speaking very bitterly against Catholics, a proceeding that was the less graceful in that a number of Catholic priests had been invited to the ceremony and, with the easy tolerance that is characteristic of the East, were showing their friendliness by a very respectful attendance.

Archbishop Nikon Sofiisky was Exarch of Georgia from 1906-08. He was assassinated in 1908, the same year Fortescue published this account.

The Church of Georgia

This Church is not to be counted among the branches of the Orthodox Communion because it has now ceased to exist. We have seen how the Georgians or Iberians were converted by St. Nino, how they became a separate body independent of the Patriarch of Antioch. The Church of Georgia under the Katholikos of Tiflis had its own rite in the Georgian language. It was almost entirely Orthodox and free from any suspicion of Nestorianism or Monophysism. In the 7th century Georgia was conquered by the Saracens, and a great persecution filled the Calendar of Tiflis with names of martyrs. In the 11th century the country was again free, and the native Georgian kings reigned at Tiflis till the beginning of the 19th century. They were continually attacked and overrun by the Persians; but, on the whole, the land was free, and the valiant Georgian warriors formed one of the bulwarks of Christendom against Islam.

Meanwhile the Church of Georgia shared the fate of the kingdom; she was persecuted whenever the Georgians were defeated, and she shared their triumph when they won. Almost inevitably this little distant Church, surrounded by other Orthodox Churches, shared their schism [here Fortescue is referring to the schism with Rome], probably hardly or not at all realizing the fact. But the Russians can scarcely afford to blame her for that, and otherwise no shadow of reproach can be brought against her. The most ancient Church of a heroic people, she deserved to remain one, and one of the most honoured of the Orthodox allies.

In 1802, however, the greatest misfortune happened to Georgia that can happen to any nation. It was made a Russian province. And from that time its Church has ceased to exist. The upstart tyrants at Petersburg, of course, cared nothing for the rights of a Church that was by five centuries more ancient and more venerable than their own, nor for the national feeling of the heroic race that for centuries had guarded the frontier of Christendom.

They simply applied their usual policy of making every one a Russian who came in their power. So at one stroke the Georgian nation and the Georgian Church were wiped out. What all the barbarians who had attacked the land unceasingly for nine hundred years — Tartars, Kurds, Persians, and Turks — had not succeeded in doing, that the Czar did with one Ukaze. All Georgians were declared members of the Russian Church; the Katholikos of Tiflis disappeared, and his place was taken by an Exarch of the Province of Georgia, who is simply a Russian bishop under the Holy Synod. Throughout the land the Russian Liturgy alone is allowed, just as at Petersburg and Moscow. The Georgian language is forbidden to be taught in schools under the direst penalties. The Georgian Uniates had to flee into more tolerant Turkey, or were forced into the Russian schism.

Quite lately, in 1904, when the storm they had brought upon themselves frightened the Russian Government into some unwilling pretence of tolerance [here Fortescue is referring to the Russian Revolution of 1905], the Georgians hoped that they, too, might at last receive better treatment. So they presented a petition to the Czar in which, with the most piteous protestations of loyalty towards the tyrant who persecutes them, they implored him to allow them again their own Church and their own language. And equally, of course, no notice has been taken of their petition. Meanwhile the only remnant of the old Georgian Church remains in the few Uniates abroad in Constantinople. It is not the Pope who destroys ancient Churches.