In 1908, a Roman Catholic priest and writer, Adrian Fortescue, published his landmark book The Orthodox Eastern Church, presenting Orthodoxy to the English-speaking world through the eyes of a very well-informed but also very papist Roman Catholic from England. In one section of the book, Fortescue surveys the Orthodox world, telling the recent history and then-current situation in each of the world’s autocephalous churches. Previously, we published sections on the ancient Pentarchy, the Church of Russia, the Church of Greece., and Georgia and Sinai.

Today, we’re moving on to the three Serbian Churches. Three? Yes, three: at the turn of the 20th century, there was not a single Serbian Orthodox Church, but rather three distinct Churches of the Serbian people, basically covering Hungary, Montenegro, and Serbia itself. The unification of the various Serbian Orthodox jurisdictions into a single Patriarchate didn’t happen until 1920.

As we’ve already seen, Fortescue is hardly an impartial observer — his contempt for Orthodoxy, and Russia in particular, comes through clearly in his writing. Nonetheless, his accounts provide a valuable record of a critical non-Orthodox perspective on the Orthodox Church at the turn of the 20th century. The full text of Fortescue’s book is available for free at The Internet Archive.

The Church of Carlovitz (1765)

Next in order of time come the Orthodox Serbs in Hungary. We have not yet mentioned three mediaeval Churches that have long ceased to exist, those of Achrida for the Bulgars, of Ipek for the Serbs, and of Tirnovo for the Roumans. All were recognized as extra-patriarchal, and so held the same position as Cyprus. The Primates of Achrida and Ipek are occasionally called Patriarchs, though they were never considered the equals of the five great Patriarchs.

We are now concerned with Ipek. In this city (now a small village in Northern Albania) St. Sabbas, the national Saint of the Serbs, set up his throne as Metropolitan of Servia in 1218. At that time the Latins held Constantinople, and the Orthodox Emperor and Patriarch had fled to Nicaea. In the midst of their own troubles, the Byzantines did not care much about the affairs of Ipek, so in 1221 they agreed that the Serbs should elect their own metropolitan, and that he should be only confirmed by the Ecumenical Patriarch.

During the troubles of the Eastern Empire in the 13th and 14th centuries, the Serbs managed to set up a great independent Power under King Stephen Dushan (+1355), which at one time stretched from the Danube to the Gulf of Corinth, and from the Adriatic to the Aegean Sea. King Stephen Dushan, who was always at war with the Empire, would not let the Imperial Patriarch rule over his Church, so in a synod of the year 1347 the Serbs declared their Church autocephalous, and gave to the Metropolitan of Ipek the title of Patriarch. Constantinople, as usual, excommunicated them, but eventually, in 1376, had to recognize the Servian Church. In 1389 came the crushing defeat of Kossovo, in which the Turks utterly annihilated Dushan’s great kingdom, and nothing more is heard of Servia as an independent Power till the revolt of 1817.

The Servian Church went on for a time after the destruction of the kingdom, but the Phanar persuaded the Porte that any sort of national organization among the Serbs, even a purely ecclesiastical one, was a danger to the Sultan’s rule, and that the best safety for the Turkish Government would be in the destruction of the Church of Ipek, and in the submission of the Orthodox Serbs to the Patriarch of Constantinople. So after centuries of bickering and machinations, at last, in 1765, the Sultan put an entire end to the Servian Church. Since then, all the Serbs in Turkey have to obey the Patriarch, although, as we shall see, they do so very unwillingly, and always hope for a great united Servian Church under a Patriarch of Ipek again.

But in three cases where the Porte does not rule over Serbs, the Ecumenical Patriarch has no authority either. One of these is that of the new kingdom of Servia, the others are those of the Churches of Carlovitz and Czernagora, which still represent the legitimate continuity from Ipek. In 1690, while the Serbs were being much harassed by the Porte and the Phanar, King Leopold I of Hungary (Emperor Leopold I, 1658-1705) invited them to come over to his land and to try the advantages of a civilized country. Thirty-seven thousand Servian families did so, and many more followed in 1737. With the approval of Arsenius III (Zrnojevitch), the shadowy Patriarch of Ipek, they founded the Orthodox Metropolitan See of Carlovitz (Karlocza on the Danube, in Slavonia). Eventually Arsenius came himself. So the See of Carlovitz has the best claim to represent the extinct Patriarchate of Ipek.

We have seen how the Orthodox Georgians fared under a Government of their own religion. The happier Orthodox Serbs under a Catholic Government have always enjoyed the most absolute freedom. In 1695 the King of Hungary guaranteed entire liberty to them to do whatever they liked, and no one has ever thought of disturbing them since. As long as any sort of See of Ipek existed (the Turks had allowed a successor (Kallinikos I) to be appointed at Ipek when Arsenius III went to Hungary), the Metropolitan of Carlovitz considered himself dependent from it, and at first he described himself as “Exarch of the throne of Ipek.” When there was no longer a throne of Ipek to be Exarch of, he became quite independent. There are now six Servian dioceses under Carlovitz scattered through Hungary and Slavonia, with twenty-seven monasteries, and just over a million of the faithful.

A last example will show the invariable tolerance and good-nature of the Government of the Habsburgs. Hitherto, the common official name for all the Orthodox in the Dual Monarchy was Greek-Oriental (griechisch-morgenlandisch); so the Church of Carlovitz was officially known as the Servian national Greek-Oriental Church. But they did not like this name. They feel very strongly that they are not Greeks; the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople had destroyed their old national Church of Ipek, and, although they are in communion with him, they cannot abide him and his ways. So they protested. The courteous statesmen at Vienna and Pesth have nothing to do with the everlasting internal quarrels of the Orthodox, but they are always studiously anxious to make every one happy. So they said that, of course, they would be delighted to do anything they could for the Serbs: What would the gentlemen like to be called? They were told; and now the official name is the Servian national Orthodox-Slav (Pravoslav) Oriental Church. This body is, of course, in communion with the Ecumenical Patriarch and with all the other Orthodox Churches, but it has no Head but Christ, and, as they sit in peace under the Habsburg double crown, this does not mean the Procurator of a Holy Directing Synod.

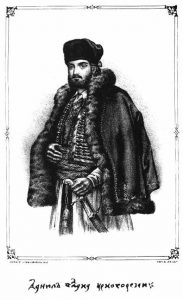

Danilo I, Metropolitan of Cetinje and founder of the House of Petrović-Njegoš, which ruled Montenegro from 1697 to 1918.

The Church of Czernagora (1765)

This Church represents the other fragment of the old Patriarchate of Ipek. The people of Czernagora (Mons Niger, Montenegro) are simply Serbs, in no way different from those of Turkey or in the new kingdom of Servia, and they form a separate principality only because of the accidents of politics. For whereas the Serbs of Turkey groan under the tyranny of the Sultan, and those of the kingdom have lately won their freedom, the valiant men of the Black Mountain have never had to submit to the barbarian. They, alone of all the Balkan Christians, have always kept their freedom; while for five centuries they waged a continual war against the Turk, they have always succeeded in driving him down from the slopes of their Black Mountain.

And so the old Servian Church, destroyed in Turkey, set up again by the exiles in Hungary, has always existed independent as the national religion of Czernagora. Till quite lately, the same person was both Prince and Bishop of the Black Mountain. In 1516, Prince George, fearing lest quarrels should weaken his people (it was an elective princedom), made them swear always to elect the bishop as their civil ruler as well. These prince-bishops were called Vladikas, and lasted till about fifty years ago. In the 18th century the Vladika Daniel I (1697-1737) succeeded in securing the succession for his own family. As Orthodox bishops have to be celibate, the line passed (by an election whose conclusion was foregone) from uncle to nephew, or from cousin to cousin.

At last, in 1852, Danilo, who succeeded his uncle as Vladika, wanted to marry, so he refused to be ordained bishop and turned the prince-bishopric into an ordinary secular princedom. Since then, another person has been elected Metropolitan of Cetinje, according to the usual Orthodox custom. The Vladikas acknowledged an at least theoretical ecclesiastical over-lordship of the Patriarchs of Ipek as long as that line existed. Since 1765, the Church of the Black Mountain has been autocephalous. Its hierarchy consists of only one bishop, the Metropolitan of Cetinje, and about ninety parish priests. It has thirteen monasteries.

Dimitrij Pavlovic became Metropolitan of Belgrade in 1905. In 1920, he was elected the first Patriarch of the united Serbian Orthodox Church.

The Church of Servia (1879)

We have already seen that there was once a great independent Servian Church, of which the centre was Ipek, and that it was destroyed by the unholy alliance of the Porte and the Phanar. In 1810 a part of the lands occupied by Serbs became independent under the famous Black George (Kara Georg). The free Serbs at once broke away from Constantinople (which had carried out its unchanging policy of trying to Hellenize them by sending them Greek bishops and allowing only Greek as the liturgical language), and put themselves under the jurisdiction of Carlovitz. In 1830 Prince Milos Obrenovitch set up an independent metropolitan at Belgrade with three suffragans. At first the Phanar was allowed the right of confirming their election, but in 1879, as a result of the greater territory given to Servia by the Berlin Congress, the Church of the land was declared entirely autocephalous. This time the Phanar, taught by the Bulgarian trouble, then at its height, made no difficulty at all.

The hierarchy of the Servian Church consists of the Metropolitan of Belgrade, who is Primate, and four other bishops. They unite to form a Holy Synod on the Russian model. There are forty-four monasteries in Servia, and one Servian monastery at Moscow is allowed by the Russian Government to send money to Belgrade and to acknowledge some sort of dependence from that metropolitan.

On the whole the relations between the established Church of Servia and the Phanar have been friendly. But there are Serbs in Macedonia who have had just the same complaint against the Patriarch as the Bulgars. North of Uskub (Skopia) by Prizrend and towards Mitrovitza especially, in that part of Macedonia that is called Old Servia, the bulk of the population is Servian. The policy of these Serbs has wavered continually. At one time they sided with the Bulgars against the Greeks, then when the Bulgars became enormously the most powerful of the Christian parties, they veered round and made common cause with the Greeks against them, and quite lately they have again begun to quarrel with the Greeks. (The situation in Macedonia is quite simple. Each of the three races — Greek, Bulgar, and Serb — wants to assert its own nationality as far as possible and as far as it can to claim Macedonia for itself. As soon as one becomes very powerful the other two unite against it. Now the Vlachs are beginning to develop a national feeling too, so there is a fourth element. The Albanians do not enter the lists because they are secure in their mountains, and no one tries to Hellenize, or Bulgarize, or Serbianate, or Vlachize them.)

After long intrigues, helped by the Government of Belgrade, the Macedonian Serbs have now succeeded in claiming the two Sees of Uskub (Skopia) and Prizrend for their countrymen. These two sees still belong to the Great Church, but they now have Servian Metropolitans, use Servian for the Holy Liturgy, and there is every probability that they, too, will break away from the Patriarchate and form yet another autocephalous Orthodox Church. The Lord Meletios, Metropolitan of Prizrend, a Greek, died in 1895. At once all the Serbs both of Servia and Macedonia united to compel the Phanar to allow a Servian successor. They succeeded in 1896, and a born Serb, Lord Dionysios, was appointed, in spite of the cries of alarm of the whole press at Athens. He uses the Servian language in his Churches, and makes no secret of his Philo-Serb policy.

The case of Uskub was more complicated. The Metropolitan Methodios, a Greek, died in 1896. The Phanar at once hastened to appoint another Greek, Ambrose, Metropolitan of Prespa, to succeed him. But when he arrived to take possession of his cathedral at Uskub he found it shut and barred and all the Servian population in revolt. The Turkish soldiers forced the church open and Lord Ambrose sang the Holy Liturgy in Greek, but in the presence of no one save the Turks who stood in the nave with fixed bayonets to keep the Serbs from a riot. He stayed in his diocese till July, 1897, and then, having found himself completely boycotted there, he went back to Constantinople.

The Phanar, since the Bulgarian schism, is at last beginning to be afraid of irritating its subjects too much, so in this case, too, it gave in, although as grudgingly as possible. Ambrose obtained perpetual leave of absence from his diocese, and a born Serb, Firmilian, was made his Protosynkellos (Vicar-General) at Uskub. In October, 1899, after long negotiations between the Government of Belgrade and the Phanar, Ambrose was transferred to Monastir (Pelagonia), and Firmilian was elected Metropolitan of Uskub. Even then the Phanar, although they had agreed to the change, sulkily refused to consecrate him. From October, 1898, till June, 1902, he had to wait, Metropolitan-elect, but not yet bishop.

At one time the Serbs even approached the Bulgarian Exarch, asking whether he would undertake to ordain Firmilian. But Russia forced the Porte to force the Patriarch to give in; and so at last the consecration took place. Sulky to the last, the Patriarch would not let it be done in either Constantinople or Uskub. At a distant monastery (Skaloti) three metropolitans met Firmilian in a sort of secret way and unwillingly consecrated him. But the Russian and Servian Consuls and the Turkish Kaimakam came to see that they really did it. He used Slavonic in the liturgy, and all the Serbs were content. The Greeks of his diocese, on the other hand, were so angry that they went into schism against him and applied to the Greek Metropolitan of Salonike for their priests. And the Phanar, though it had to submit to Firmilian, makes no secret of its sympathy with them. But the Porte now recognizes these two sees, Prizrend and Uskub, as a new millet separate from the “Roman nation” under the civil jurisdiction of the Patriarch. This means that they will soon become an autocephalous Church, and there will be one more fraction of the dismembered Ecumenical Patriarchate to register.