St Nicholas Orthodox church, Mahon, 1769

Introduction

At the turn of this century two important collections of documents came to light in the north of Scotland[i], the content of which should adjust our understanding of the first steps of the Orthodox Church in what is now the United States. Recently I was able to travel to the now Spanish Balearic island of Minorca in the Mediterranean Sea. What I found there, combined with information from these Scottish documents and some of my research on the life and times of Colonel Philip Ludwell III, has opened up for me substantially new horizons. I hope to share some of these with you in this article.

We often fail to realize that our history is not set in stone and will require revisiting from time to time as new information about the past comes to light. This can be unsettling and even expensive, as often considerable time and money has been invested in retelling stories that subsequently can be shown to be at best less than complete. It can take a long time, if ever, for a new narrative to be widely known and embraced, and even then in turn it may again require modification as further discoveries are made.

I have been a member of the Orthodox Church for almost thirty-five years and for as long as I remember there have been two broadly disparate stories of the beginning of Orthodoxy in the America: The Russian Orthodox Church and its specifically American offshoot, the Orthodox Church in America (OCA), point to the Russian mission that landed in Kodiak, Alaska in 1794 as the starting point. At the same time the Greek Orthodox Archdiocese has embraced the story of the New Smyrna colony in Florida that brought Orthodox believers to these shores in 1768. Ten years ago I published my initial research about Colonel Philip Ludwell III, a Virginia landowner who converted to Orthodoxy in 1738 and a distinct website now exists about that story.

From the perspective of some I have spoken with both the story of the Ludwell family and that of the New Smyrna colony lack one vital component in attributing to them the mantle of the beginnings of Orthodox Church life in what is now the United States: Their lack of clergy. In the hope that you are sitting comfortably and to entice you to read on at length I hope to show here that there is much more to the Orthodox components of the story of New Smyrna than have previously been recognized and that these intersect at several points with the story of the Ludwell family: Both these stories, and even that of the Kodiak mission, are part of a wider narrative. I hope to write in more detail about this meta-narrative and the consequential intersection at a later date.

To encourage reading this entire lengthy article I will share my conclusions first, before exploring how I have arrived at these:

- There was a Greek-speaking Orthodox priest in the New Smyrna at the beginning of the colony in 1768.

- His name was probably Fr Theoclitos.

- He would have commemorated the Holy Governing Synod of the Church of Russia during church services.

I will now review the sources and then follow the trail that leads to three conclusions above, taking each in turn.

A Greek Speaking Orthodox Priest in New Smyrna

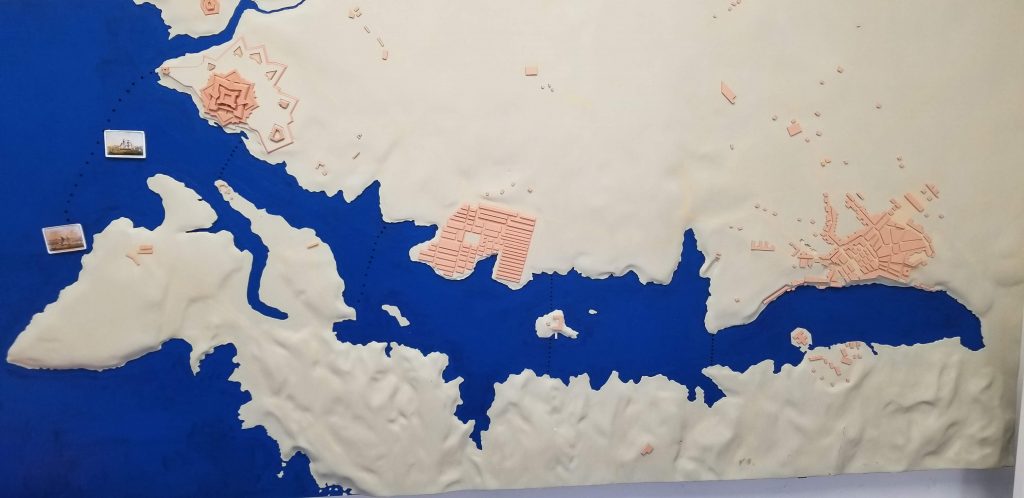

Mahon harbor in the 18th century. St Philip’s Castle top left and the city of Mahon top right.

On March 28, 1768 a fleet of eight ships set sail from the city of Mahón, one of the world’s finest natural harbors, located on the then British Mediterranean island of Minorca.

Mahon Harbor today.

The New Smyrna colonists sailed from Mahón on March 31 to Gibraltar (also a British possession), where the Mediterranean Sea ends, before beginning their transatlantic journey to Florida. The first of the ships made landfall in North America sometime before the 22nd of June when instructions were given by Governor Grant for settlers to be disembarked at the future site of New Smyrna. During the often-turbulent crossing the colonists initial official numbers would be reduced from 1403 to 1255. Nonetheless they still constituted the largest single settlement of European colonists in what would become the United States. No one is certain of the exact places of origins of the original settlers who left Mahón, but a broad consensus exists that by far the greatest number were from the island of Minorca. This fact in turn has led to an assumption that the vast majority of the settlers were Roman Catholics. As we shall see this need not follow.

Almost a century before Dr Turnbull began to gather the colonists the English government was recognizing the potential usefulness of peoples from Greek speaking parts of the Mediterranean to what we would now call the American South. In 1675 Sir William Berkeley, the Governor of Virginia, proposed that Greeks be brought to Virginia from the Morea (Peloponnesus) in southern Greece to engage in silk production and other agricultural projects. In the same year, a Mr Ball, the English consul in Livorno (or Leghorn), on what is now the north west coast of Italy, proposed to the English Parliamentary Committee of the Plantations regarding the Mainotti (descendants of the ancient Spartans),

to procure many thousands of them to go and inhabit any secure part of America under his Majesty’s dominion. They have been turbulent, and the Turk endeavours what possible to drive them out of the country, laying a tax of so much per head, taking away their children, and not suffering them to exercise their religion, which is of the Greek Church.

The same proposal was raised again in the 1763 work of William Knox, Hints Respecting the Settlement of Florida. Knox, who later became the British Under Secretary of State for American Affairs wrote regarding the Greeks:

I am well assured that great numbers of these people might be induced to become our Subjects if their mode of worship was tolerated and the expense of their transportation defrayed, their priests who are the proper persons to employ might be easily brought to persuade them to emigrate & our island of Minorca would be a convenient place for them to rendezvous at.

Knox’s proposal was to be implemented by Dr Turnbull several years later. Turnbull obtained his first grant of land in the East Florida colony in 1766 and wrote in July of that year to Governor Grant of his intention for settling a Greek colony in that Province. The following January Grant wrote to the Earl of Shelburne, the British Southern Secretary, that:

a church has been reserved in this town for that purpose and that town lots shall be given adjoining the said church to such Greek inhabitants as shall choose to settle at St. Augustine–that all possible attention shall be shown to Greek Priests who shall have Glebe’s [land owned by a parish to provide income for its clergy] assigned to them upon their arrival in this Province.

The scale of what was being planned becomes clearer in an April 1767 letter from Turnbull to Grant where he writes of obtaining a ship to be continually employed in carrying Greek families from Port Mahon to East Florida, thus giving Turnbull the means for introducing into your Province at least a thousand Greeks a year. That same month a report of the Board of Trade to the Earl of Shelburne recommends for East Florida that £100 should be allowed to the first Priest of the Greek Church which shall be established in that colony.

Turnbull spent the spring, summer and fall of 1767 traversing the Mediterranean as far as Smyrna in Asia Minor and including the Peloponnesus of southern Greece. He writes from Leghorn on the 22nd of January 1768, I have sent a ship to Mahon with Greeks. But when by February 21 Turnbull was in Mahón he writes that he has not been successful in obtaining an Orthodox priest for his colonists as I found that the Turks were apprised of my Scheme by the Levant Company’s consuls [the British trading company in the Ottoman Empire who viewed Turnbull’s Florida development plans as potential competition], and that the Priest, engaged to meet me, was stop’t by his Patriarch at Constantinople, and consequently could not fulfill his contract with me…

At this point Turnbull also states that he has about seven hundred colonists, including an expected two hundred Greeks who were caught in a storm at sea en route to Minorca. By March 9 the missing Greeks had arrived in Mahón and Turnbull claims the overall number of colonists had increased to twelve hundred,thanks mostly to taking local women as wives. By April 24 Turnbull’s fleet had already left Gibraltar and was in sight of the Portuguese island of Madeira in the Atlantic Ocean. His letter written at this point tells us that

I have upwards of fourteen hundred men, women, and children in the eight ships, the greatest part of them from the Island of Minorca, British born subjects and a very sober industrious people. The Turkey Co. [another name for the Levant Company] took measures to prevent my having many Greeks, however, hundreds of families will be brought from that country.

It took until almost the end of August for all the colonists to finally arrive in Florida. Turnbull writes on July 27

that the last ship is arrived with the People in good health and Spirits, tho’ they have been now four months onboard without setting a foot on shore. The ship proceeds with them tomorrow to land them at the mouth of Hillsborough River.

But something must have gone awry with these plans as a little less than a month later he states that the last ship, the Charming Betsey, had arrived in St. Augustine and was putting passengers ashore at the settlement on August 20th. The day before this a mutiny had broken out amongst the colonists and a ship was seized. Turnbull blames this almost entirely on an Italian colonist, Carlo Forni, whom he describes as an execrable villain. But then, as Turnbull goes on to give his account of the mutiny in detail, he reveals that there had been an Orthodox clergyman with the colonists who were already at the new settlement, writing that

The Greek priest was forced onto a boat with some other Greeks with whom the boat sunk and the priest was drowned.

So despite Turnbull having stated in February that he had been unable to procure the services of a Greek Priest, it seems that one was subsequently found. Turnbull confirms the existence of this priest and the manner of his passing in a later letter to Governor Grant on May 30 1769. He writes about complaints from existing colonists that the New Smyrna settlers are foreigners and Catholics, then continues:

I can engage to make than anything I please, and I would make them Turks tomorrow if I thought it would make them better planters for it, but this I do not intend nor to turn apostle nor act a Luther to reform them, Tho’ I will answer that this will be very soon a Protestant settlement if a Clergyman is sent among them. A hundred pounds was set aside by the Board of Trade for a Greek Priest for our settlement, I brought a Priest with me but he was drowned by accident. [Emphasis mine]

To understand who this priest most likely was, and from whence he came, it time to learn something of the surprising history of the Orthodox Church of St Nicholas of Bari in Mahón, Minorca.

Minorca and its trading links in the 18th century

The Identity of the Greek Speaking Priest with the New Smyrna Colony

Some years ago, early on in my research on Philip Ludwell III, I came across a surprising piece of news that was printed in the Virginia Gazette of April 4, 1771. On the third column of the front page there is a brief report filed in Leghorn, Italy, the previous November. It is worth quoting in full:

LEGHORN, November 15. Letters from Mahon advise that two chests,one containing the Gospel,most curiously bound,with golden covers, and a very curious Set of Communion Plate, all richly embossed, and the other containing equally magnificent Vestments for the Priest, of the Greek Church at Mahon, had been sent as a Present by the Empress of Russia, which were received by them the 3d of October, the Coronation Day of the Empress.

It is only in the past few weeks that I have been able to research the story behind this news and connect it to that of the New Smyrna Colony.

To contextualize all this we need to go back to the beginning of the 18th century, to a conflict known as “The War of the Spanish Succession.” As its name implies this was a struggle rooted in the question of who would succeed to the throne of Spain. It pitted France, then the most powerful country in Europe, together with Spain and others, against England, Holland and their allies. The conflict concluded with the signing of the Treaty of Utrecht in 1713. Under its terms England acquired from Spain both Gibraltar at the far southern end of the Iberian peninsular and the small and most easterly of the Balearic Islands, Minorca. From France the English gained Acadia (Nova Scotia) on what is now the Atlantic seaboard of Canada. In all these newly acquired territories Roman Catholicism was the majority religion and by the terms of the treaty they were to be allowed to continue to freely practice their faith.

With specific regard to the population of Minorca the British undertook to allow the freedom to worship in the Roman Catholic faith, with the important caveat that for the protection of that religion, measures will be taken which will not be at variance with the civil government and laws of Great Britain.

The ambiguity of this declaration would allow the British to implement in Minorca the policy we have already seen was being articulated regarding resettling Greeks in the south of the American colonies: Thus the British looked to bring Greeks into Minorca, with a view to diluting the island’s staunchly Catholic population. Their presence there can be documented from 1713 onwards. Very few seem to have come from parts of the Mediterranean controlled by the Ottoman Turks: More typically they were from islands under Venetian or Genoese control or other port cities such as the aforementioned Leghorn or Marseille, France, that already had established Greek colonies. Often their background was Eastern Catholic (the Genoese, unlike the Venetians, typically only allowed communities to follow Orthodox liturgical forms if they also recognized Papal authority,) but by the 1730’s there must have been an identifiable number of Orthodox Greeks in Minorca. In that decade they were visited by Bishop Theoklitos (Polyeidis) of the diocese of Polyani and Kilkis in northern Greece and Grand Ecclesiarch of Mt Athos, who taught and ministered amongst them. Nevertheless the Orthodox struggled to establish themselves in Minorca, facing considerable opposition from the Roman Catholic authorities there. To win them over it seems the Orthodox were willing to also portray themselves as Eastern Rite Catholics and so in 1743 wrote to the Roman Catholic Vicar General of Minorca for permission to bring over a priest from the Genoese controlled island of Corsica to serve the Catholic Christian community of the Greek Church. This priest, Fr John George Cassara, accordingly arrived but was rejected by the Roman Catholic authorities in Minorca when it came to light that he had not received the requisite civil and ecclesiastical papers to leave his native Corsica.

At this point in 1744 a new British Governor arrived in Minorca and undertook to help the Greeks there by bringing there situation to the attention of Prince Ivan Shcherbatov, the Russian Minister Plenipotentiary in London. This resulted in a group of Greek merchants from Minorca, together with their priest Fr Gregory Kassava (probably the same man as the aforementioned John Cassara,) traveling to London in the spring of 1744 to petition the British King George III to be granted British citizenship and thereby gain full freedom in their practice of the Orthodox Faith. Once in London they were aided in this endeavor by Fr Bartholomew Cassano the priest of the Russian church there who six years earlier had received the young Philip Ludwell III into the Orthodox Church. The Minorcan Greeks specifically requested permission to erect an Orthodox church in Mahón with a cemetery and a priest to serve them. The King, on the advice of the Board of Trade and Plantations, granted the said permission in November 1745.

This decision provoked a furious reaction from the Roman Catholic authorities in Minorca who threatened with excommunication any stonemasons who offered to work on the church’s construction or to those who supplied materials for it. Through the firm hand of the British authorities this opposition was eventually overcome, but it was not until November 1749 that construction of the church began. The two wealthiest merchants in the Minorcan Greek community, Manolis Cifando and Nicholas Alexiano, donated the land for this and it took five years for the building of the temple to be completed. During this time, in 1751, Cifando returned to his native Patmos and the Alexiano family became the undisputed leaders of the Greek community in Minorca.

St Nicholas of Bari, Mahon today.

When finished the church was dedicated to St Nicholas and its dedication is referred to thereafter as either St Nicholas of Myra or of Bari. The latter dedication may be further evidence of Russian involvement in the formation of the parish as typically only Orthodox of the Russian Church celebrate the Feast of the Translation of the Relics of St Nicholas to Bari, whereas the Greeks do not. In any event it was (and still is) a magnificent building that cost in excess of £20,000. This would be more than four million dollars in today’s money.

I have not yet been able to learn from where or when the new church found its clergy but within two years of the completion of the building there were two Orthodox priests on Minorca: Their names were Theoclitos and Seraphim. Together with twenty-three other members of the Greek community they took part in the defense of St Philip’s Castle at the entrance to Mahón harbor, when the French besieged this in 1756 at the beginning of the Seven Years War. Following the fall of the castle these Greeks, including the priests, were evacuated with the British troops to Gibraltar. There the Governor, in recognition of their service and circumstances, granted them a stipend until they were able to return to Minorca in 1763 at the end of the war when it reverted to British rule. Crucially, the document from the archive of the Government of Gibraltar identifies the leader of the Greeks as one Theodore Alexiano, nephew of the aforementioned Nicholas Alexiano, who fours years after his return to Minorca would become Dr Andrew Turnbull’s principal agent for procuring colonists and supplies for New Smyrna.

During the seven years of French control in Minorca from 1756-1763 the Orthodox parish was shut down. This process would repeat itself barely two decades later when in August 1781 the Spanish began to reoccupy the island. It would be fully returned to their control under the terms of the Treaty of Versailles in 1783 that formally concluded the American War of Independence. Thus in 1782 we can document the priest-monk Seraphim relocating from Mahón to Livorno, taking with him the holy vessels from the Orthodox parish of St Nicholas.

St Nicholas of Bari today, Central dome

So what became of Fr Theoclitos between the reopening of the church in Minorca in 1763 and its final closure in 1782? We cannot be certain without further evidence but it seems to be a more than tenable assumption that he was the priest taken by Turnbull with the colonists to Florida, who tragically met death by drowning within two months of his arrival in the New World. Recent research by the Spanish historian Pedro Pablo Moreno Lucas-Torres points to more than twenty members of the Orthodox parish in Mahón leaving with Turnbull’s expedition to form the New Smyrna Colony. Given these numbers and the plans that already anticipated the presence of an Orthodox priest in Florida it would be less than surprising if one of the two priests in Mahón did in fact join the expedition. The Spanish historian Hernandez estimated that by the time of the New Smyrna colony’s departure the Greek community in Minorca may have numbered as many as 2000 or ten percent of the island’s population. This number is probably too high. The church today has room for a congregation of around two hundred seated on benches. Nonetheless it was clearly a numerically significant group and after two generations inter-marriage with the local population had occurred. All this means that persons typically counted as Minorcan in expedition records because of their names should not necessarily be assumed to be Roman Catholics.

Now we must turn more closely to the question of Russian involvement in the church of St Nicholas, Mahón and by implications in that of its daughter parish in the colony of New Smyrna, Florida.

New Smyrna: The First Russian Church in America?

If you visit Mahón today and make your way to the Roman Catholic church of the Immaculate Conception in Cós de Gràcia street you will find yourself inside the splendid Byzantine basilica that was the church of St Nicholas of Bari. You will encounter on the south side a large inscription in three languages: Greek, Russian and Latin, that mark a burial place. It reads:

Here lies the body of the Russian nobleman Andreas, the son of Gregory Spiridoff, who served the Russian imperial fleet to the highest degree, as the helper of his father, Knight Spiridoff, admiral and general-commander of the fleet. He was born in 1750 on the first day of September. He died in 1769, on November 21, having lived 19 years and 2 months. I died during the stay here of the Russian fleet directed towards the archipelago by the admiral and knight Spiridoff. You are gone now and your father and your friends have wept for you, but your remains lay to rest in friendly soil. Your tomb will announce the exploits of Catherine and will teach the new route of the Russian Argonauts.

Spiridoff tomb in former Orthodox church of St Nicholas Mahon

This grave reveals the presence of the Russian fleet in Minorca only one and a half years after Turnbull and his colonists had left Mahón for Florida. The Russians had sailed all the way from their base at Kronstadt in the Baltic and by the time they entered the Mediterranean were suffering much from scurvy. Many ordinary sailors were to be buried in the cliff caves of Cala Figuera in Minorca but the full Orthodox funeral was served for the Admiral’s son at the church of St Nicholas of Bari in Mahón. Thankfully the Italian Minorcan artist Giuseppe Chiesa (whose daughter would marry a member of the Orthodox parish) was also present at this service and left a magnificent pen and ink sketch of it that gives a vivid impression of the grandeur of the church at that time.

St Nicholas Orthodox church, Mahon, 1769, Spiridoff funeral

The gift of the Gospel book, Communion vessels and vestments by the Empress Catherine the Great to the parish in Mahón that the Virginia Gazette reports were received there in October 1770 were almost certainly by way of thanks to the parish for their hospitality to the Russian fleet one year earlier. That fleet had in fact gone on to sail to the Eastern Mediterranean where at the battle of Chesma in July 1770 they inflicted the greatest defeat on the Ottoman navy since Lepanto almost 200 years earlier.

As the eighteenth century saw the emergence of the British Empire so also the Russian Empire was emerging as a great power from its Muscovite roots. Following their visit to Minorca in 1769 the British offered the Russians permanent use of Mahón for a Mediterranean fleet. A decade later when Britain was engaged in the war to retain its American colonies it sought help from Russia in the form of troops. In return it offered Minorca to Russia. The deal was struck by the British Prime Minister Lord North with the Russian Prince Potemkin, but ultimately declined by the Empress Catherine the Great who did not want to abandon her policy of armed neutrality.

But even a generation before this we have seen that Russian involvement was present in gaining the Greeks their own church in Minorca. I plan to write elsewhere in more detail about the specific links that existed between the Orthodox church in Mahón and the parish in London that was under the jurisdiction of the Holy Governing Synod of the Orthodox Church of Russia. These links exist both in the 1740’s and later at the time the New Smyrna colonists left Minorca. For example, the Turnbull documents discovered in Scotland reveal that one of the financial backers of the New Smyrna colony was Peter Paradise, the father of John Paradise, who in 1769 married Lucy Ludwell, the youngest daughter of Philip Ludwell III. The London church records show the Ludwell and Paradise families receiving holy communion regularly in the 1760’s. It should be remembered that whilst the parish in London is typically referred to as “Russian” its membership in the eighteenth century seems to have been predominantly Greek or Anglo convert and the designation as “Russian” stems from the locus of its ecclesiastical obedience.

Given that the Church of Russia was the only one of the local Orthodox churches not under Ottoman domination in this period it is hardly surprising that it either directly assumed oversight of such Orthodox communities as existed then in Western Europe or, as in the case of the parishes in Leghorn (Livorno) and Marseilles it wielded considerable influence over them. It was only after the Greeks fought and gained their independence from the Ottomans in the 1820’s and early 1830’s that this situation changed, leading in London to the creation of a distinct Greek Orthodox parish.

Thus we should not be surprised to learn that when the Spanish forced the close of the church of St Nicholas of Bari in Mahón in 1782 documents of the Holy Synod of Russia formally transfer the sacred vessels etc. of that temple to the parish in Leghorn (Livorno), making it explicit that the Minorcan parish was under their juridiction. Following this the Priest monk Seraphim who came to Leghorn from Minorca in 1782 and sought to place himself there under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church of Russia. Only after much uproar did Constantinople succeed in preventing this. Nonetheless the parish in Leghorn did eventually pass under Russian jurisdiction for a period of time.

For most of the eighteenth century Minorca was a British territory. With the Orthodox church in London being under Russian jurisdiction, albeit being primarily Greek speaking in membership, it should be expected that the parish in Mahón would follow suit. Likewise its short-lived daughter in the then British colony of East Florida.

Icons in former church of St Nicholas, Mahon today.

[i] 1. The Papers of General James Grant (1722-1806) Governor of British East Florida from 1763-1771. Until the end of the twentieth century these were housed at Ballindalloch Castle in the Scottish Highlands, the ancestral home of General Grant’s family and known only to family members. In 1999 a member of the family brought these to the attention of the Library of Congress.

- At about the same time a treasure trove of papers originally belonging to Dr Andrew Turnbull were found in an attic in the north-eastern Scottish city of Dundee. Turnbull was the proprietor of the New Smyrna colony and these documents greatly enhance our knowledge of the colony. Turnbull’s papers were part of the larger collection of the Haldane-Duncan family, Earls of Camperdown. The fourth and last Earl of Camperdown died without heirs in 1933, having spent most of his adult life in Massachusetts following his marriage to a Boston socialite. His great great uncle was Sir William Duncan, physician-extraordinary to King George III. Duncan is a frequent correspondent in the Turnbull papers and this presumably accounts for how they ended up in the Earl of Camperdown’s native Dundee. These papers were collected and transcribed in 2003.

Both sources are now easily accessible thanks to the University of East Florida.