In the early 20th century, no fewer than seven of the world’s Orthodox Churches had succession crises (Cyprus, Greece, Constantinople, Moscow, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem). Meletios Metaxakis was involved in five of them.

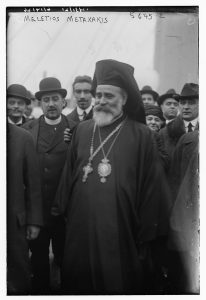

Meletios is best remembered for his tenure as Ecumenical Patriarch, but in fact he held that position for less than two years — elected in November 1921, enthroned in February 1922, left Constantinople in July 1923 and resigned that October (retroactive to September). Granted, he packed more into those 20-odd months than most Patriarchs would do in decades.

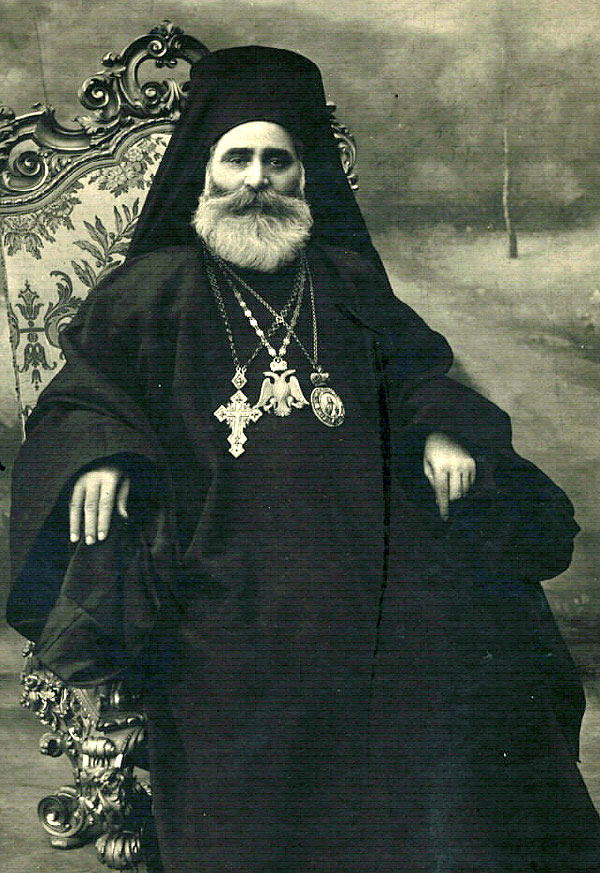

To some, Meletios is a hero, a visionary and progressive leader of Orthodoxy during a tumultuous period. To others, he’s the ultimate villain, a self-serving Freemason and enemy to Holy Tradition. But whatever you think of him, Meletios looms large over the history of Orthodoxy in the modern age. Today, I’m going to provide a very basic overview of his life.

***

The future Patriarch Meletios was born Emmanuel Metaxakis in Crete in 1871. When he was 18 years old, he moved to Jerusalem. There are different explanations for this move — I’ve heard that he participated in some kind of insurgency against the Turks in Crete, and I’ve also heard that he had a big fight with his father and left home. Of course, it’s possible that both stories are true.

Two years later, his spiritual father Archbishop Benjamin became Patriarch of Antioch (this was when Antioch was still controlled by the ethnically Greek Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre). Patriarch Benjamin tonsured Emmanuel a monk with the name “Meletios” and ordained him a hierodeacon. Meletios initially served in the Patriarchate of Antioch. He attended Holy Cross Seminary in Jerusalem, graduating in 1900. After his graduation at the age of 29, he became a member of the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre and was appointed Secretary of the Holy Synod of Jerusalem.

Meletios traveled widely during this period, visiting Alexandria, Austria, and Russia. At this time, the Church of Cyprus was in the midst of a protracted succession crisis. Cyprus has been autocephalous since ancient times, but its hierarchy was never large, and by the early 20th century it was left with just two bishops — both named Kyrillos — who were contending to fill the vacant position of Archbishop. Neither would give way to the other, and in 1906 the Hellenic Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Jerusalem sent representatives to the island in an attempt to find a resolution. The 35-year-old Meletios represented the Patriarchate of Jerusalem.

Two years later, Meletios found himself persona non grata in his own Patriarchate. In the wake of the Young Turk Revolution of 1908, the Patriarch of Jerusalem was inclined to increase the involvement of the native Arab population in the Patriarchate, as a way to avoid future problems. Meletios seems to have opposed this, and he also seems to have been part of a failed plot to depose Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem. Meletios was expelled from Palestine for “activity against the Holy Sepulchre.” He ended up in Istanbul. In 1910, he was elected Metropolitan of Kition. He was not yet forty years old. Shortly after his consecration, in March 1910, Meletios became a Freemason at the Harmony Lodge in Constantinople.

Meletios was a candidate for Ecumenical Patriarch in 1912 but was not elected. In 1918, he was elected Archbishop of Athens, thanks largely to his connection with the Greek Prime Minister Eleftherios Venizelos. That summer, Meletios traveled to the United States to organize the Greek Orthodox communities in America.

***

Back in 1908, the Ecumenical Patriarchate had issued a tomos relinquishing any claim to jurisdiction over the Greek diaspora in favor of the Church of Greece. This, incidentally, was the first time on record that Canon 28 of Chalcedon was used to justify a claim by the EP to any sort of general jurisdiction over territories not claimed by another autocephalous church. But this claim was in its infancy, applying, in the 1908 tomos, only to ethnic Greek communities rather than to all Orthodox irrespective of nationality. In any case, the Church of Greece didn’t send a bishop to America for a decade after the tomos, until the arrival of Archbishop Meletios and his friend Bishop Alexander of Rodostolon.

In the summer of 1918, Meletios and Alexander worked to organize the Greek-American communities into an archdiocese, and when Meletios returned to Greece after a few months, he left Alexander in charge of the fledgling Greek Archdiocese.

In Greece, Meletios’ fortunes were linked to those of Prime Minister Venizelos. When Venizelos fell from power in 1920, Meletios found himself deposed as Archbishop of Athens. With nowhere to go, he returned to the United States in February 1921, where his friend Bishop Alexander welcomed him. Alexander, who up to this point had been a bishop of the Church of Greece, issued an encyclical declaring that he did not recognize the newly-appointed Holy Synod of Greece and “until the situation there is cleared up in accordance with the Canons of the Church,” he would recognize the Ecumenical Patriarchate as his ecclesiastical authority.

For much of 1921, then, both Meletios and Alexander were in a sort of limbo, in between the Churches of Greece and Constantinople. The two bishops finished organizing the Greek Archdiocese, formally incorporating the Archdiocese under New York law and presiding over the first Clergy-Laity Congress in September. Then, in November, Meletios’ fortunes turned again, and he was suddenly elected Ecumenical Patriarch. It has long been rumored that British influence was decisive in securing Meletios’ election, although there appears to be evidence in the UK National Archives that the British government decided to remain neutral in the election.

In any event, of the 68 bishops entrusted with a vote, only 13 were present at the meeting, while 5 more gave their vote to one of those 13 attendees. So that left 18 votes, and 16 went to Meletios. Seven of the absent bishop-electors were metropolitans, and those seven metropolitans comprised a majority of Constantinople’s 12-member Holy Synod. These seven gathered in Athens and declared Meletios’ election to be invalid. They telegraphed Meletios in America, ordering him not to come to Constantinople. He ignored the order. Meanwhile, the Holy Synod of Greece deposed Meletios. He ignored that, too.

***

Meletios arrived in Constantinople in February 1922 and was enthroned as Patriarch. One of his first acts was to repeal the 1908 tomos and declare the right of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to “direct supervision and management of all Orthodox parishes located outside the borders of the Local Orthodox Churches, without exception, in Europe, America, and other places.” He also issued a tomos of autocephaly to the Church of Czechoslovakia and spent a week negotiating with a Serbian Orthodox delegation about the autocephaly of the Church of Serbia. All of what I just described took place in March 1922. In May, Meletios issued another tomos, this one transferring the Greek Archdiocese of North and South America from the jurisdiction of Athens to that of Constantinople.

In August, Meletios and his Holy Synod decided to recognize the validity of Anglican holy orders, and the following month he wrote a letter to the national convention of the Episcopal Church in America announcing the decision. (For background on this, see Fr Kyrill Johnson’s account of his discussion with Meletios on this topic.) As this was happening, the Greek military overthrew King Constantine’s government, and the new government reversed the state’s anti-Meletios position and ordered the Church of Greece to recognize Meletios as Ecumenical Patriarch. The Archbishop of Athens refused and was immediately deposed.

The disastrous Greco-Turkish war was coming to a close, and the Greeks in Turkey were doomed to suffer from the fallout. Meletios, seeing the writing on the wall, met with his Synod twice in October to consider moving the Patriarchate out of Turkey. In November, the Lausanne Peace Conference began, just as three renegade bishops in Turkey set up a “Turkish Orthodox Church” with support from the new Turkish government, which was seeking to undermine the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

In January 1923, the Turkish delegation to the Lausanne Peace Conference formally demanded that the Ecumenical Patriarchate be removed from Turkey — preferably to Mount Athos. The other delegates proposed a compromise, whereby the Ecumenical Patriarch could remain in Constantinople but would be stripped of all political and administrative authority. Venizelos, acting as the leader of the Greek delegation, even offered to sacrifice his friend Patriarch Meletios, proposing that Meletios – an enemy of the Turks – would resign if the Patriarchate were allowed to remain in Turkey. The Turks agreed to the deal.

Then, on January 30, Greece and Turkey agreed to a “population exchange,” under which most of the Muslims in Greece would be deported to Turkey, and most of the Greeks in Turkey would be deported to Greece. Some two million people were deported, including about 1.5 million Greek Orthodox Christians living in Turkey.

In February, by now sort of a dead man walking, Meletios invited all of the Orthodox Churches to a meeting in Constantinople, mainly to consider revisions to the church calendar, as well as remarriage of clergy.

In March, a delegation from the newly-formed Albanian Orthodox Church arrived in Constantinople to meet with Meletios. It expected to receive formal recognition of Albanian autocephaly, but the Meletios only acknowledged partial autonomy.

On May 1, the forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey formally took effect. Thousands and thousands of Orthodox Christians were forced to abandon their homelands. Just days after this, Meletios convened the landmark “Pan-Orthodox Congress,” which ended in June with the adoption of the “Revised Julian Calendar.” On June 1, Meletios was attacked by a mob connected with the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” who dragged him down a flight of stairs, tore at his robes, and demanded that he resign. He shouted back, “Let them hang me if they will, but now I shall not retire!” An Allied police force in Constantinople intervened and saved Meletios, who very well could have been killed otherwise.

Besides the calendar, the other big topic at the Pan-Orthodox Congress was the remarriage of widowed clergy. The Congress decided to maintain the tradition of the Church in prohibiting clergy remarriage, but to allow such remarriages in exceptional cases, “making provision for the terrible position of widowed clergy at the present time,” i.e., in the wake of World War I. A final determination was referred to a future ecumenical council.

The next month – July – Meletios separately received the Churches of Finland and Estonia – which had previously been part of the Russian Orthodox Church – under the jurisdiction of Constantinople. These would be Meletios’ final acts as Ecumenical Patriarch: within days, under pressure from the new leaders in Turkey, Meletios left the country on a British steamship bound for Mount Athos. As a British account put it a few years later, Meletios was saved “only by the swift action of British military authorities who practically kidnapped him. Two minutes later,–they would have been too late.”

In October, the Republic of Turkey was created. On October 2, literally as the Allied evacuation of Constantinople was taking place, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was meeting at the Phanar. Papa Efthim, leader of the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” burst into the room with a guard of Turkish police. He ordered the Holy Synod to declare Meletios to be deposed within ten minutes. The Holy Synod complied. Then the Turkish police expelled six of the eight Holy Synod members, along with the Locum Tenens, from the building. (All of the expelled bishops had sees outside of Turkey.) Papa Efthim then replaced the seven expelled bishops with his own partisans. At that moment, it appeared that the Ecumenical Patriarchate either no longer existed, or had just been taken over by a coup d’etat.

Meanwhile, Meletios was in Greece, and was thinking about moving the Ecumenical Patriarchate to Thessaloniki. Both the Greek government and the Church of Greece opposed this, and they finally convinced Meletios to resign as Patriarch. He signed a document backdated to September 20, after obtaining assurances from Turkey that they would open the path for a new patriarchal election, not controlled by Papa Efthim and the “Turkish Orthodox Church.” (By backdating the abdication, Meletios was attempting to undercut the actions of Papa Efthim on October 2.)

***

Meletios laid low for a bit, living quietly in a suburb of Athens, before resurfacing in September 1925. Patriarch Photios of Alexandria had just died en route home from an ecumenical gathering in Stockholm, and Meletios was named as a top candidate to succeed him. He placed a distant third in a preliminary vote in February 1926, but in June, he won the election by a razor-thin margin. According to the New York Times report on the election, Meletios declared that now Alexandria, rather than the weakened Constantinople, would be first among equals in the Orthodox Church: Meletios decided “to resume his old title as head of the Eastern Church and to have Alexandria assume its ancient authority as the capital of that Church.”

In June 1927, Meletios deposed a priest named Basil Lebentes, who was in Morocco. In ancient times, Morocco had been under the jurisdiction of the Church of Rome, and now its status was rather ambiguous. Lebentes appealed to the Ecumenical Patriarch, who claimed jurisdiction over Morocco. Meletios responded by claiming all of Africa for Alexandria. “All Africa” would soon be added to the formal title of the Patriarch of Alexandria, although the Ecumenical Patriarchate would not recognize this until the 21st century.

Meletios, architect of the New Calendar, now found himself primate of a Church that was still on the Old. In June 1927, he attempted to call a pan-Orthodox council to address the calendar issue; his dream was to convince Antioch and Jerusalem to adopt the New Calendar as well. But none of the other Churches accepted his invitation to a council. He ultimately managed to have Alexandria’s Holy Synod approve the New Calendar in February 1928. It took effect that October.

For centuries, the status of the Archbishop of Sinai was very ambiguous. At times, he claimed to be autocephalous, and the activity of the Archbishop and his monks in Egypt caused friction with the Patriarchate of Alexandria. In June 1928, Meletios banned the monks from Sinai from serving in their metochion in Cairo. The two sides were at an impasse for more than four years, until Meletios and the Archbishop of Sinai signed an agreement, finally resolving Sinai’s status.

In 1930, Meletios led an Orthodox delegation to the Lambeth Conference of the Church of England. This was a major step toward the hoped-for union of Orthodoxy and Anglicanism, which of course never happened, but which Meletios worked toward throughout his entire ministry.

One of the running themes of Meletios’ tenure as Patriarch of Alexandria was his effort to strip the laity of their role in Patriarchal elections. This caused significant public backlash, and in August 1931, Meletios sent a private memorandum to his old ally Venizelos, asking for his intervention to quell the public dissatisfaction. The memo was made public by a newspaper a couple months later, only adding to the turmoil. Eventually, Meletios did issue new rules that banned the laity from Patriarchal elections, but after his death those rules were declared to be invalid, and the next Patriarch was elected by the hierarchy and laity together.

Basil Lebentes, the priest whom Meletios had deposed back in 1927, had fled to America, and in 1932 the new Greek Archbishop (and future Ecumenical Patriarch) Athenagoras wanted to place Lebentes in a parish in New York. This led to a dispute between Meletios and Athenagoras. The Ecumenical Patriarchate declared that Meletios’ deposition of Lebentes had been uncanonical, but to avoid an open war with Meletios, they didn’t reverse the action but rather asked Meletios to do so. I’m not 100% clear on how all this panned out, but it’s a fascinating little episode involving two of the most influential men in 20th century Orthodoxy.

In 1931, Patriarch Damianos of Jerusalem died. He was the same Patriarch who had expelled Meletios from Jerusalem back in 1908. Meletios immediately emerged as a top candidate to replace him. While the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre, which controls the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, was generally opposed to Meletios’ candidacy, the Patriarchate was in constant financial turmoil (it had been selling off lands to Jewish settlers for years as a result). Meletios was the favorite of the Anglicans, who would, it was said, contribute large sums to the Patriarchate if only Meletios were elected — and if the Patriarchate would grant the Anglicans major concessions regarding the use of the holy places in Palestine.

In 1934, two native Ugandan men, who had been part of the non-canonical “African Orthodox Church,” approached Meletios to seek reception into the Orthodox Church. Meletios received them and sent them Orthodox liturgical books. This marks the beginning of the Orthodox mission to the indigenous people of sub-Saharan Africa, which, under Meletios’ successors, has transformed the Patriarchate of Alexandria.

The throne of St James in Jerusalem was vacant for four years, as Meletios and his rival Timotheus battled for the see. In June 1935, Meletios suffered a heart attack. On July 22, 1935, Timotheus was elected Patriarch of Jerusalem. Less than a week later, Meletios died. He was just shy of 64 years old.

***

In an obituary for Meletios, the French journal Echoes d’Orient wrote, “A daring innovator, he undertook profound reforms in Athens, Constantinople and Alexandria, but he was constantly the butt of stubborn opposition from the partisans of tradition. His interference in political affairs, his ties with Freemasonry, as well as his friendly negotiations with the Anglicans have earned him many criticisms.”

I used a wide variety of contemporary sources for this article. Many of these came from issues of the journal Echoes d’Orient, as well as American newspapers. Another useful source was the paper “Two Ecumenical Patriarchs from America: Meletios IV Metaxakis (1921-1923) and Athenagoras I Spyrou (1948-1972)” by Professor Vasil T. Stavridis and published in The Greek Orthodox Theological Review in 1999.

A very needed biographical beginning in the English language. A history of this ecclesiastical thief and his destructive thievery is much needed!!

A Leb and Russophile fawning over Anti Greek propaganda and lies

I am indeed Lebanese, but I’m not sure what I’ve written that constitutes anti-Greek propaganda. I try to be even-handed in my approach to the messy reality of Orthodox history. If I have said anything that is inaccurate, I’m always happy to be corrected.

Thank you Matthew for this explanation. Speaking as an Orthodox Christian born into the Greek Orthodox Church in Canada, this is welcome information.

Wow ! Unbelievable Father very disturbing sad and tragic. Becoming a Freemason is a shocking revelation as the devil entered Judas the evil ones energies were at work in this arrogant and most prideful man. How gracious the Lord is in allowing him

So much time to come to his senses and repent until the Lord intervened , thanks be to God

Meletios sounds like the ‘Energizer Bunny’ of Orthodoxy! Keeps going and going and going…..

You need to seek out the History of ROCOR published by St. Nectarios Press. It is on the internet. You completely ignore ROCOR’s role.

Meletios harassed St. Nectarios of Aegina.