In recent days, U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo visited the Ecumenical Patriarchate in Istanbul. After the meeting, Pompeo tweeted that the Ecumenical Patriarchate is a “key partner” of the United States. This is no secret; the close relationship between the United States government and the Ecumenical Patriarchate is well known to go back decades, to the very beginning of the Cold War. But as documents from the U.S. State Department reveal, the American government’s interest in Orthodoxy, and in the Ecumenical Patriarchate in particular, actually go back a bit further, at least to 1940, prior to the U.S. entry into World War II.

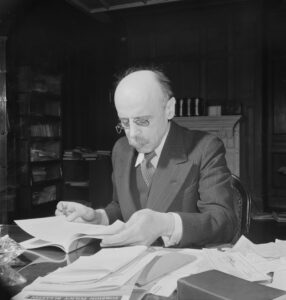

On March 15, 1940, President Franklin Roosevelt wrote a letter to his State Department, floating the idea of establishing U.S. contacts with an influential figure in the Islamic world, with the aim of promoting “world peace.” Assistant Secretary of State Adolf Berle — a member of FDR’s famous “Brain Trust” — responded a few days later with a suggestion: His Majesty Ibn Saud, King of Saudi Arabia. These days, Saudi Arabia is a longstanding ally of the United States, but in 1940 the US-Saudi relationship was in its infancy. The one fly in the ointment was Turkey, as Berle noted: “The only danger lies in possible political repercussions in Turkey.” He planned a meeting with the Turkish Ambassador.

Then, on March 26, Berle sent another memo to FDR, this time focusing on the Orthodox Church:

There has been referred to us a letter from the Hellenic Youth Association to you asking that you appoint a representative to confer with the Greek Orthodox Church in the matter of peace. The letter is unimportant, as the Greek Orthodox groups here have little influence.

But the letter suggests a line which might be worth considering. The Greek Orthodox Church has a good deal of influence in the Near East, the Balkans and the Eastern Mediterranean; and some faint residue of influence in southern Russia. There is no recognized head, Patriarchs having separate jurisdiction in various regions [i. e. Istanbul, Alexandria, Antioch and Jerusalem]; but the acknowledged senior is the Patriarch at Istanbul. He could probably convene or consult with the other Patriarchs.

This might be a line worth following. Certainly the contact with the Vatican, plus the contact with the King of Italy, has materially altered the whole diplomatic situation in Italy. Conceivably, the combination of contact with Turkey, with Ibn-Saud and the Mohammedans, and with the Greek Orthodox Church, might materially influence the Near East. As far as I can see, that situation rests now entirely on the attitude of Turkey; it is, in fact, the only solid obstacle which prevents the caving in of the eastern Mediterranean structure. Today’s despatches indicate that the Russians have not abandoned their desires to move southward toward the Dardanelles.

Like the move toward the Mohammedans, this ought to be prepared a little in advance by consultation with the Turkish Ambassador here.

Roosevelt loved the idea and responded to Berle the next day.

I have your memorandum in regard to informal discussions with the Greek Orthodox Church and I wish you would talk the matter over with the Secretary, bearing in mind the following thoughts: Unlike the Roman Catholic Church, the Greek Orthodox Church is not wholly centralized under a single head, even though the Patriarch at Istanbul is recognized as the Senior. As I understand it, the other Patriarchs are, in effect, in control within their own jurisdictions.

I wish you would, therefore, consider the following possibility: To appoint Lincoln MacVeagh on a special mission to visit the Patriarch at Istanbul and possibly also the other three Patriarchs, in order to confer with them on the general subject of peace, much as Myron Taylor has been conferring in Rome.

At the same time we might send another Envoy to accomplish the same purpose in the Mohammedan world, conferring (with the full approval of the President of Turkey, of course) with the Mohammedan leader in Turkey proper and the leaders possibly in Saudi-Arabia. After a survey of these it might be advisable to extend such a visit to Egypt and Iraq and Iran—all of them independent countries.

A couple weeks later, Berle met with the Turkish Ambassador, which he summarized in a report dated April 5. His main focus was on the Islamic world; the Orthodox were clearly of secondary importance. The Turkish Ambassador had various concerns about the Islamic envoy idea, in large part because it could conflict with Turkey’s secularist ideology. On the Orthodox, Berle noted, “The possible [sic] sending of a representative to the heads of the Greek Orthodox church was touched on, but only briefly. The Turkish government plainly would take much the same attitude towards that representation as it did towards a move to establish contact with the Mohammedan church.”

The next day, April 6, Berle wrote directly to FDR, “This matter was discussed with the Turkish Ambassador. He pointed out the extreme delicacy of the question in Turkey, owing to the Turkish policy of reducing the political importance of the Mohammedan church. He thought, however, that his government would consider the matter sympathetically, in view of the objective; and suggested that we make inquiry through Ankara.” Berle recommended that Roosevelt write a personal letter to the President of Turkey on the subject.

The next document we have on this matter is an April 24 report from Wallace Murray, Chief of the Division of Near Eastern Affairs. The Turkish Ambassador had visited Murray and informed him that the whole U.S. proposal put Turkey in an awkward position, given that it had “carefully excluded religious leaders from any participation in political affairs.” It would be better, said the Ambassador, if the U.S. would drop the whole thing. Incidentally, the Orthodox were not mentioned at all in that discussion — the focus, instead, was on Islam.

Finally, on May 4, Murray had another meeting with the Turkish Ambassador. “The Ambassador said that he desired again to make it clear, and trusted that he had sufficiently emphasized during previous conversations, that in case such a proposal came to fruition Turkey would find herself in an embarrassing position, either if she were approached or if she were ignored.” Murray’s report on that May 4, 1940 meeting is followed by this bracketed note: “[The plan for consultation with leaders of the Eastern Orthodox and Mohammedan faiths was abandoned.]”

***

Five months later, October 28, 1940, the Italian invasion of Greece began. (This is the famous “Όχι Day,” celebrated every year by Greeks throughout the world.) In April 1941, Nazi forces invaded Greece to help their Italian allies, and the Nazi occupation of Greece began. The following March, Archbishop Athenagoras, then head of the Greek Archdiocese of North and South America, began his work in assisting U.S. intelligence agents. The relationship between Athenagoras and the U.S. government grew, reaching its crescendo when Athenagoras was elected Ecumenical Patriarch in 1948 and flew to Istanbul on a plane loaned to him by President Truman. The ties between the U.S. and the Ecumenical Patriarchate would become even stronger during the Cold War.

If we want to identify a point of origin, when the U.S. first recognized the potential strategic value of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and Orthodoxy in general, it may well be that these 1940 documents are the smoking gun. While the plan to coordinate with Orthodox leaders was apparently abandoned in May 1940, by the end of the decade the United States was deeply involved in Orthodox affairs.

Leave a Reply