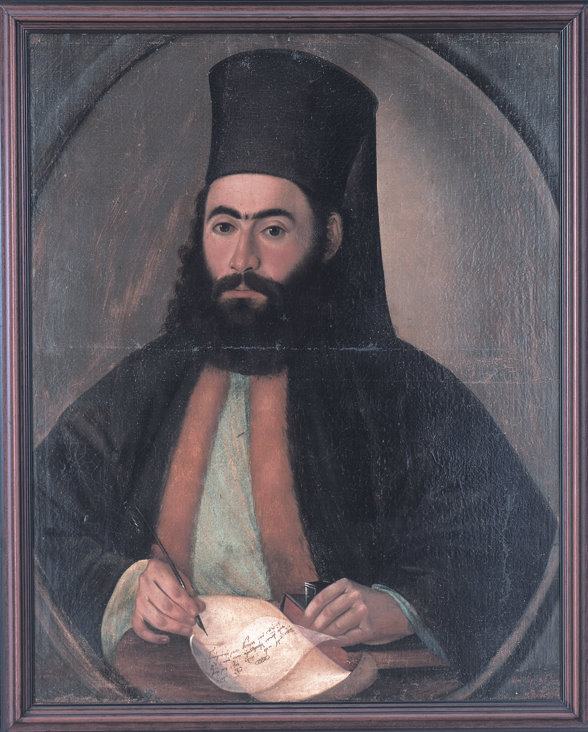

In October 1818, Archbishop Kyprianos of Cyprus met with representatives of the Filiki Eteria, the Greek secret society that was preparing to launch a war for independence. While some sources claim that he was initiated into the secret society, there appears to be no direct evidence for this. On the contrary, only three years earlier, the Archbishop had issued a letter warning against secret societies and declaring all Freemasons to be excommunicated due to the incompatibility of Freemasonry with the Orthodox faith. The Archbishop also emphasized that the followers of Freemasonry were disobedient to the Ottoman Sultan, and he called for the support of the Ottoman state to suppress Masonic activity. Given that the members of Filiki Eteria were Freemasons, it seems implausible that Archbishop Kyprianos would have become a member himself. The Archbishop did offer financial support to the revolutionaries, but he seems to have been slow in actually delivering on that offer.

Under Archbishop Kyprianos, the church leadership in Cyprus had reached a new threshold of power and influence on the island. This was a threat to the Ottoman establishment. In early 1820, a new Ottoman governor arrived in Cyprus – Kuchuk Mehmed. As one 19th century source describes him, he was “a man of imperious and dissembling temper, whom the Captan Pasha had chosen purposely to destroy the influence of the Greek Primate,” that is, Archbishop Kyprianos. An English visitor to Cyprus the following year described the new governor in this way: “His features were those of a most ferocious and savage fellow. He had nothing noble and dignified in his manners, which usually characterize Turks of high rank. As soon as we were seated he poured out a flood of inconceivable words against Archbishop Kyprianos and the Greeks… May I say that the behaviour of this man during our conversation was that of an animal rather than a human. It was quite clear that he was enjoying the thought of greater disasters and atrocities against the unfortunate Greeks.”

The Greek Revolution was formally launched on Annunciation in 1821. Shortly after this, on Pascha, the Ottoman authorities executed Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V and numerous other Orthodox leaders. Still more were imprisoned. Within weeks of Patriarch Gregory’s execution, representatives of the Filiki Eteria secret society arrived in Cyprus and began distributing pro-revolutionary flyers. The Turks intercepted the literature, and the Ottoman governor Kuchuk Mehmed passed this on to his superiors in Constantinople, along with a list of hundreds of leading Greek Cypriots whom he claimed to be guilty of treason, including Archbishop Kyprianos, three other bishops, and the abbots of all the monasteries of Cyprus.

In response, the Sublime Porte dispatched 4,000 troops from Syria, and the governor ordered a disarmament of all Greek Cypriots. Archbishop Kyprianos issued a letter to his flock, urging them to submit to the decree. Although the Porte did not approve the governor’s request to execute the leading Greeks on the island, he began executing other Greek Orthodox people anyway, focusing his attention on the wealthiest and confiscating their property for himself.

Here is how a visiting Englishman described Archbishop Kyprianos’s response to the crisis:

One evening I was invited to a dinner at the archiepiscopal palace, during which a Turkish soldier came to deliver a message to the Archbishop whom he addressed in most abusive language. The Archbishop remained composed and spoke to him in a very calm and decisive manner… The other bishops and priests at the table were pale and terrified, and to them the Archbishop gave some encouragement. He was, indeed, very moved and disturbed over the whole affair, but one could still see in his noble face, lighted with energy, his determination to defend his suffering flock…. He spoke to all of us at the table, and no one interrupted him, as if he was delivering his farewell address, a speech of a good shepherd to his harassed flock… This man, highly eminent for his learning and piety as well as for his unshaken fortitude, was the last rallying point of the wretched Greeks; and his frequent remonstrances and reproaches, on behalf of his people, had rendered him very obnoxious to the Turkish authorities.

The Archbishop went on to tell the Englishman, “My death is not far off. I know that they are only awaiting the right moment to kill me.” On May 16, he wrote a letter to his flock, calling on them to trust in God, to repent of their sins, and to “reject every passion and coldness which we have towards our brothers.”

In early July, Governor Mehmet finally received permission from the Sublime Porte to commence executions. The European consuls in Cyprus offered asylum to Archbishop Kyprianos, but he declined. On July 9, the executions began with the hanging of Archbishop Kyprianos outside the governor’s palace. One account describes the Archbishop’s final moments in this way: “Taking in his hand the noose from the executioner, he made three times the sign of the cross… and then turned to his executioner and in a firm voice said, ‘Execute the command of your cruel master.’”

The governor then had Kyprianos’s secretary hanged, and the three other bishops of Cyprus (Chrysanthos of Paphos, Meletios of Kition, and Lavrentios of Kyrenia) were beheaded. Other laymen were also beheaded, and over the next five days, the governor had hundreds of Greek Cypriots executed, most of them wealthy and influential. He confiscated all of their property and appointed replacements for the four executed bishops.

While the martyrdom of Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory gets the most attention, Archbishop Kyprianos’s death, and those of his fellow bishops and members of his flock, are equally worthy of memory.

Main Sources

Michalis N. Michael, “Kyprianos, 1810-21: An Orthodox Cleric ‘Administering Politics’ in an Ottoman Island,” in Andrekos Varnava and Michalis N. Michael, eds., The Archbishops of Cyprus in the Modern Age: The Changing Role of the Archbishop-Ethnarch, their Identities and Politics, Cambridge Scholars Publishing (2013), 40-68.

John A. Koumoulides, “Early Forms of Ethnic Conflict in Cyprus: Archbishop Kyprianos of Cyprus and the War for Greek Independence 1821,” Cyprus Review (1996).

Memory eternal our Saints. Between Islam and Freemasons God’s flock are lost. If Islam washed hate out of it’s heart they would have worked with us. We would have stopped the West from enslaving them once and forever. But they never understand!