Athenagoras Spyrou was elected Ecumenical Patriarch in 1948 thanks largely to the influence of the United States government, particularly Secretary of State George Marshall. At the time, Marshall had consulted the powerful Greek-American businessman Spyros Skouras, and Skouras recommended the Athenagoras, who was then the Archbishop of the Greek Archdiocese of North and South America. Athenagoras was already well-known to the U.S. government, having cooperated with U.S. intelligence agencies since the early 1940s. According to Skouras, “General Marshall, in his capacity as Secretary of State, had no hesitation in sponsoring His Holiness and thanks mainly to his efforts and influence, the Holy Synod decided to elect Archbishop Athenagoras as Patriarch and the Turkish Government agreed to his election.”

Two decades later, Athenagoras, who was past 80 years old and knew his end was approaching, tried to set the table for his succession. Once again, he enlisted Spyros Skouras, who tried to lobby the Nixon Administration to intervene, just as the Truman Administration had done before. But the geopolitical situation had changed in the intervening decades, and Nixon wouldn’t even grant an audience to Skouras to discuss the issue.

Athenagoras was not the only person thinking about EP succession. According to an April 1970 British government report, “the Turkish Government was exercising pressure on the Patriarchate on the question of succession. [Greek Foreign Minister] Pipinelis said that the Turks had already indicatd that Iakovos, Archbishop of North and South America, would be unacceptable, if only because his ‘personal record’ was not impeccable; he had been deposed of his Turkish citizenship because he had evaded his military service and had made a number of declarations hostile to the Turkish Government.” The British report speculated that “the Turks might insist on the election of a complete nonentity” and raised concerns about the worst-case scenario of the expulsion of the Patriarchate from Istanbul.

The following month, on May 25, 1970, the Prefecture of Istanbul issued a directive on the selection of future Ecumenical Patriarchs. Under these rules, the Holy Synod of Constantinople would draw up a list of candidates within a certain period of time, and this list would be submitted to the Vali (Governor) of Istanbul. The Governor would then remove any names deemed objectionable by the Turkish authorities and return the revised list to the Holy Synod. The Synod would elect a Patriarch from the preapproved candidates. (According to testimony by U.S. Secretary of State John Kerry, “The decrees also hold that if a patriarch cannot be elected within eight days, the Governor of Istanbul can appoint a patriarch – though this aspect of the decree has never been tested.” See pages 132-133 of this document.)

A British government report cited the official Turkish position, expressed by a Turkish Foreign Ministry official shortly before the official May 25 decree, who informed the British, “As regards the election of a new Patriarch this was conducted by the members of the Synod. They were required to submit to the Vali [Prefect] of Istanbul a list of not less than three candidates and the Vali could delete certain names from that list. Once he had exercised this right, the Turkish authorities would make no difficulties over the election and any subsequent ceremonies provided that these were not on a Vatican scale.”

A June 1971 U.S. State Department report on Greece touched on the Patriarchal succession issue from the perspective of strained Greek-Turkish relations: “Athens has apparently not worked out a modus vivendi with Ankara to insure an untroubled succession to the 86-year old Athenagoras, the Ecumenical Patriarch resident in Istanbul, in case of his death or resignation. The prestige of Greece is intimately tied to the Patriarchate, and Turkish authorities hold a virtual veto over the succession election. If controversy should attend the first patriarchal succession in more than 23 years, relations between the two governments could be seriously worsened, even to the point of jeopardizing the continued residence of the 20,000 Greek citizens in Istanbul.” (In fact, in 1964 Greek citizens and dual nationals were expelled from Turkey. By 1971, then, all Greek Orthodox in Turkey would have been Turkish citizens.)

Two months after this report, Spyros Skouras died, having failed in his mission to coordinate with the U.S. government about Ecumenical Patriarchate succession. (For all the details about Skouras, the 1948 EP election, and his lobbying efforts to the Nixon Administration, see my article on the subject.) The same month that Skouras died — August 1971 — the Turkish government forcibly closed the Greek Orthodox theological school at Halki, which remains a sore point to this day.

In February 1972, Turkish authorities issued an additional regulation: a public notary must witness the election. (Alexandris, The Greek Minority of Istanbul & Greek-Turkish Relations, 1918-1974, 306.) In March, the U.S. Embassy in Ankara reported that Turkey seemed to expect Metropolitan Meliton of Chalcedon to become the next Patriarch. (This was noted in a telegram sent by U.S. Ambassador to Greece Henry Tasca to the State Department.) Then, on July 7, 1972, Patriarch Athenagoras died.

***

The day Athenagoras died, July 7, 1972, U.S. Vice President Spiro Agnew (himself a Greek-American, although not an Orthodox Christian) was in Houston, Texas, where the Greek Archdiocese of North and South America was holding its Clergy-Laity Congress. That morning, Agnew met with Archbishop Iakovos, the head of the Greek Archdiocese. Iakovos badly wanted to become the next Ecumenical Patriarch, but he was at odds with the Turkish government and technically ineligible because he was not a Turkish citizen. Iakovos begged Agnew to attend Athenagoras’s funeral in Istanbul, but Agnew declined, instead speculating that perhaps President Nixon could appoint Iakovos himself to lead an ecumenical delegation to the funeral.

After speaking with Iakovos, Agnew called Secretary of State Henry Kissinger. We have a transcript of that call, which has been declassified. Kissinger was immediately uneasy about appointing Iakovos to represent the United States at the funeral, saying, “I have to make sure that this doesn’t take sides in succession.” Agnew pushed a bit, pointing out the value of the Greek vote: “The Archdiocese of North and South America is where our ball game is — we have tremendous support in this great community.” He cautioned against “being too considerate of the Turkish bishops of no advantage to us whatsoever,” focusing instead on securing “a very great block of supportive voters.” Kissinger countered, “I don’t give a damn about the Turkish bishops. I give a damn about the Turkish government.” But he promised to look into the idea. Over the next few days, U.S. officials had multiple conversations about this with Turkish diplomats.

Two days later, a Turkish official called the State Department’s Bureau of Near Eastern Affairs, adamantly rejecting the possibility of Archbishop Iakovos entering Turkey. According to a State Department telegram the following day, “Turk Charge Yegen telephoned NEA/TUR Director Dillon at home to say he had received instructions from Ankara to tell USG [U.S. Government] that decision re entry of Archbishop Iakovos had been reviewed at highest level of GOT [Government of Turkey]; that Iakovos would not be permitted to enter Turkey; that Iakovos was an ex-Turkish citizen who had lost citizenship and who had worked against best interests of Turkey; that his presence in Turkey during delicate period following death of Patriarch was considered particularly undesirable. Yegen added that ‘in our opinion’ Iakovos wanted to gain entry in order to politick for succession to Patriarch, which was matter of ‘great sensitivity’ in Turkey.”

At around the same time, Vice President Agnew had another phone call with Secretary Kissinger. Kissinger delivered essentially the same message as the State Department telegram had done: “I have checked this matter all over the place… Our information is that this has been considered at the highest level in Turkey and that they’re absolutely adamant about it. The reason is that a Greek Patriarch in Istanbul is not just a religious figure and that, apparently as far as I understand, they don’t want to have Yakovos [sic] as their Patriarch.”

On July 12, Iakovos sent a telegram to George H.W. Bush, the future President who had recently been Ambassador to the United Nations. Iakovos asked Bush to make an “immediate personal expression of protest to the United Nations in reaction to the unprecedented Turkish Government interference in the election of the Ecumenical Patriarch by virtue of their demands that the next Patriarch be approved by them and that elections be finalized within 72 hours.”

The next day, July 13, Harold Saunders, a key National Security Council official, sent a memo to Kissinger. Saunders was straight to the point: “The desirability of our continued non-involvement seems clear.” Saunders then launched into a discussion of the arrangements between the Turkish government and the Ecumenical Patriarchate. After describing the process by which the Governor of Istanbul must preapprove nominees, Saunders said, “This process has been going on since Athenagoras’ funeral on Tuesday. We understand that the Holy Synod submitted a list (which includes Meliton [of Chalcedon], the compromise candidate) to the Istanbul Governor after the Turks insisted they do so within 72 hours. The Turkish press says the Turks, after they edit the list, may be asking that the election take place within the next 72 hours. Finally, the Turk government has indicated publicly that if the election procedures are not followed it may have to appoint a new Patriarch though it has told our embassy in Ankara that it wishes to avoid this.”

This whole situation enraged Archbishop Iakovos, who found this level of Turkish interference to be outrageous. Saunders observed, “Iakovos probably wants more time to lobby for support and the Turks want the matter to end quickly so that it does not become politicized. In any case, Iakovos seems incorrect in saying that the Turkish government’s involvement is ‘unprecedented.’ Not only have they been involved in practice — they seem to have assured the election of Athenagoras in 1948 by pressing other candidates to stand aside. The problem today is that they are blocking Iakovos.” And 1948 was not the only example of Turkish interference in Ecumenical Patriarchate elections. For example, see my article on the tumultuous 1917-1925 period, in which the Turkish government meddled extensively in the internal affairs of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. And of course, many examples from the Ottoman period could be cited, in which the Ottoman authorities routinely removed Ecumenical Patriarchs and vetoed candidates.

The U.S. Embassy in Ankara told Saunders that the Turks had promised not to be “heavy-handed in editing the list of candidates.” This would prove to be a lie: in the end, not only did the Turkish government veto Archbishop Iakovos, but they also nixed the other front-runner, Metropolitan Meliton of Chalcedon. According to a later account by the current Ecumenical Patriarch, Bartholomew, in the 1972 election the Turks actually vetoed no fewer than four candidates. (The Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World goes even further, claiming that five candidates were eliminated.) Of Meliton, the Associated Press would write that “the Turkish Government, seeking to keep the Patriarchate under its control, had struck from the list of acceptable candidates the name of Metropolitan Meliton. Meliton, an outspoken progressive, had been considered the favorite for election.”

Saunders’s memo to Kissinger ends with a rather forlorn conclusion: “The fact is that the Turks for years have been harassing the Patriarchate, half wishing it would decide to withdraw. Given the Orthodox desire to stay in Istanbul, the Greeks at least seem to have resigned themselves to living with the situation. We are not likely to be able to change it.”

***

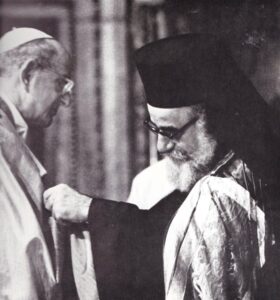

The election of the next Ecumenical Patriarch took place at the Phanar in Istanbul on July 16. With the front-runners Meliton and Iakovos, along with at least two others, out of the running, the final three candidates were Metropolitans Dimitrios of Imbros and Tenedos, Nicholas of Anneon, and Gabriel of Colonia. The Associated Press reported, “All three were supported by the Meliton faction, to which eight of the 15 Metropolitans belong.” The fifteen Holy Synod members voted via secret ballot, placing slips of paper into a silver urn that sat in front of the Patriarchal throne. Dimitrios won 12 of the 15 votes, and Meliton — as Metropolitan of Chalcedon, the man who presided over the election — announced the result and cried out “Axios! Axios!”

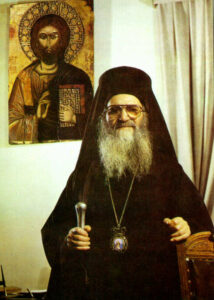

Dimitrios was a seriously dark-horse candidate, a humble and heretofore obscure teacher and pastor. Reporting on the election the Associated Press wrote, “Informants said Dimitrios would be guided in most matters by Meliton, who is a strong advocate of Orthodox unity. Dimitrios is essentially a pastoral cleric with little experience in matters of state, they said.”

Patriarch Dimitrios remained on the throne for nearly two decades, until his death in 1991. The election of his successor, Patriarch Bartholomew, went much more smoothly, with the Istanbul Governor not vetoing any candidates.

Leave a Reply