The oldest autocephalous church in the world attained its current form in 1845.

Today, depending on whom you ask, there are fourteen or fifteen or maybe sixteen (or seventeen?) autocephalous Orthodox Churches in the world. In dispute are the Orthodox Church in America (OCA), which everyone accepts as canonical but most churches don’t accept as autocephalous, and the Orthodox Church of Ukraine (OCU), the autocephaly and canonicity of which is rejected by most churches, recognized only by the churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Cyprus, and Greece (and in some cases, only parts of those churches). And now, we have another claimant to autocephaly: the “Macedonian Orthodox Church” (or, if you prefer, the “Archbishopric of Ohrid”), which was declared autocephalous by the Serbian Orthodox Church just hours before the publication of this article. As of now, only the Serbian Church has recognized this new autocephaly, and no one is sure what will happen next.

Leaving those disagreements aside, let’s examine each of the fourteen universally-recognized autocephalous churches. When did they become autocephalous? When did the current ecclesiastical structures that govern those churches come into being? This seemingly straightforward question is actually quite the can of worms…

We’ll go through the diptychs in reverse order, from bottom to top, using the diptychs according to the Ecumenical Patriarchate (EP) prior to the formation of the OCU. (“Diptychs” refers to the list of autocephalous primates that are commemorated liturgically by each autocephalous primate. Every bishop commemorates the bishop in his church who “ranks” immediately above him; so, for example, a Metropolitan in the Patriarchate of Antioch will commemorate Patriarch John of Antioch, while Patriarch John himself will commemorate all of the other autocephalous primates, beginning with the Ecumenical Patriarch and continuing on down to the primate of the Czech Lands and Slovakia.)

Czech Lands and Slovakia

The present-day Church of the Czech Lands and Slovakia has its origins in the mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius in the 9th century. The modern structure of the church really dates to the years following World War I. The country of Czechoslovakia was established in 1918, and in 1921, the Serbian Patriarch consecrated a bishop for the new country, Bishop Gorazd, who was really the father of the modern church there. Bishop Gorazd was a saintly figure who was martyred by the Nazis in 1942 and has since been glorified as a saint.

After World War II, Czechoslovakia came into the Soviet orbit, and consequently, the Czech church came into the orbit of the Moscow Patriarchate (MP). In 1951, the MP issued a Tomos of Autocephaly to the Church of Czechoslovakia. This was not accepted by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Decades later, in 1998, the EP issued its own Tomos of Autocephaly to the church, and since then, it’s been universally recognized as autocephalous. Even so, the anniversary date of its autocephaly remains in dispute, with many in the Czech church considering their autocephaly to date to 1951, which has caused friction with the EP.

Poland

The territory of Poland has been embattled for centuries, changing hands between various empires. Prior to World War I, this region was part of the Russian Empire, and its Orthodox church was part of the Moscow Patriarchate. Following World War I, Poland achieved its independence, and in 1921, Metropolitan George of Warsaw, the Moscow-appointed primate, signed an agreement with the Polish government to establish the Orthodox Church of Poland as independent of the Moscow Patriarchate. Three Polish bishops opposed this action, and, according to news reports, Metropolitan George had them deposed and banished to monasteries. In 1923, a pro-Moscow monk assassinated Metropolitan George. The following year, the Ecumenical Patriarchate granted a Tomos of Autocephaly to the Polish Church.

After World War II, Poland fell under Soviet domination, and the Moscow Patriarchate issued its own Tomos of Autocephaly to the Polish Church in 1948. Since then, the Polish Church has been universally recognized as autocephalous. The Polish case is obviously similar to that of the Czech Lands and Slovakia, with the main difference being that the EP, rather than Moscow, acted first with respect to Poland.

Albania

The land of Albania first received the Orthodox faith in the Apostolic era. The Ottoman conquest led many of the region’s Christians to convert to Islam. The church in Albania was under the Ecumenical Patriarchate throughout this era. In 1912, an independent Albanian state was established. A decade later, in 1922, an Albanian Orthodox Congress convened and declared the Albanian Church to be autocephalous. The Ecumenical Patriarchate was not particularly keen on this, and the following year, the EP recognized only partial autonomy for Albania. In 1929, without EP approval, the bishops in Albania established a Holy Synod, and the EP reacted by deposing all of them. Relations thawed seven years later, when an Albanian church congress voted to formally apologize to the EP. The next year, 1937, the EP issued a Tomos of Autocephaly to the Albanian Church.

After World War II, Albania came under Communist control. The Albanian primate, Archbishop Kristofor, was deposed in 1949 due to his opposition to the Communist regime. He was replaced by a more compliant archbishop, and things went from bad to worse. In 1967, the Albanian primate was arrested and imprisoned, and the Albanian Church was cruelly repressed. No new primate was elected, and for all intents and purposes, the Albanian Church ceased to exist. After the fall of communism, in 1991, the Ecumenical Patriarchate sent Metropolitan Anastasios Yannoulatos as Patriarchal Exarch to revive the Albanian Church. The following year, the EP elected Anastasios to be the Archbishop of Albania and restored Albania’s autocephalous status, which was accepted by all of the other Orthodox Churches.

Greece

The Greek Revolution began in 1821, and the churches in the territory that broke away from the Ottoman Empire were likewise disconnected from the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In 1833, following the accession of the new Greek King Otho (who was a Roman Catholic), the German-controlled Greek government brought together the bishops in Greece and declared the Church of Greece to be autocephalous – independent of the EP, but very much subservient to the Greek government. The Church initially had no primate and became, effectively, a department of the state, which had the power to appoint members to the Holy Synod, and no synodal decision was valid without the signature of the state procurator. Although the bishops ostensibly had authority over the “internal” affairs of the church, these internal affairs were narrowly defined. A lay government official, the “state procurator,” coordinated the Holy Synod, in a model that was explicitly based on the Russian synodal system (discussed below). The government could intervene in many areas that would seem to be obviously internal to the church, such as the scheduling of liturgical services, ordinations of clergy, and the number and boundaries of dioceses. The Holy Synod was forbidden from communicating with any foreign authority without going through the government – including spiritual authorities such as other autocephalous churches.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate initially rejected all of this, but by 1850, it was clear that Greece wasn’t coming back into the Patriarchate, and the EP issued a Tomos of Autocephaly, which was accepted by all of the other Orthodox Churches. The Tomos imposed certain conditions on the Church of Greece: the Ecumenical Patriarch must be commemorated at the Divine Liturgy and must be the provider of Holy Chrism, and the Church of Greece must submit all important questions to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Following the Tomos, the Church of Greece restructured internally: the Diocese of Attica became the Metropolis of Athens, and the bishop there took the title “Metropolitan” and was made the permanent president of the Holy Synod – in other words, Greece now had a primate. In 1923, all of the dioceses were raised to metropolis status, and the Metropolitan of Athens was given the title “Archbishop” (which, in the Greek tradition, is a higher rank than metropolitan).

As different Greek-speaking regions left the Ottoman Empire and joined Greece, the question arose about how the churches in these areas should relate to the EP and the Church of Greece. Some areas were simply annexed into the Athens-based church, while others (Crete and Mount Athos) remain directly subordinate to the EP, with no relation to the Church of Greece. The so-called “New Lands,” including Thessaloniki, annexed by Greece after the Balkan Wars in the 1910s, are a fascinating case: the bishops of these New Lands are elected by the Church of Greece but confirmed by the EP, and they are listed as bishops of both churches.

To this day, the Church of Greece remains closely tied with the Greek state, with clergy paid by the state and the primatial election submitted to a government official.

Cyprus

The Church of Cyprus is the first “ancient” church on the list. It originated with the Apostles themselves, and its independence was confirmed at the Third Ecumenical Council in 431. The island was conquered by various foreign powers over the centuries, and under Frankish and Venetian rule from 1260 to 1571, the autocephaly of the Church of Cyprus was suppressed. In 1571, the Ottomans took control of Cyprus, which proved to be a major improvement over the previous three centuries of Roman Catholic rule. In 1572, a synod of the four ancient Patriarchs restored Cyprus’s autocephaly.

Although nominally “autocephalous” since 1572, it’s only in the 21st century that Cyprus has truly been able to govern its own internal affairs without the involvement of other churches. At the outset of the Greek Revolution in 1821, the Ottoman governor of Cyprus massacred the entire hierarchy of Cyprus, which had to be reconstituted from outside. At the turn of the 20th century, the entire episcopate of Cyprus was reduced to just two bishops (both named Kyrillos), who vied to become the next Archbishop. The Patriarchates of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Jerusalem all got involved in the dispute. Later, due to British meddling in the 1930s, there ended up being just a single bishop in Cyprus, and the British government tried to have the Ecumenical Patriarch appoint a new Archbishop, which would have completely abrogated Cyprus’ autocephaly.

In 1973, Archbishop Makarios – who was both the church primate and the President of Cyprus – faced a rebellion of three of the five Cypriot bishops, and the episcopate was too small to handle the crisis internally. Makarios called for a “Major Synod,” consisting of the neighboring churches of Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, Jerusalem, and Greece. Constantinople and Greece didn’t participate, but the other churches held the synod (chaired by the Patriarch of Alexandria) and resolved the situation. Two more Major Synods occurred in the 21st century, both being necessary because Cyprus didn’t have enough bishops on its own. Most recently, in 2006, the hierarchy of Cyprus requested a Major Synod to deal with the tragic situation involving Archbishop Chrysostomos I, who had fallen into a coma and needed to be retired, but Cyprus lacked enough bishops to do it on their own (canonically, the deposition of a bishop requires at least twelve other bishops). The resulting Synod, chaired by Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew, declared the primatial throne of Cyprus vacant, paving the way for local archiepiscopal elections. Since then, the hierarchy of Cyprus has grown considerably, which means that Cyprus will probably not need to call upon other churches to help resolve its internal matters in the future.

All of this raises the question, was Cyprus in fact “autocephalous” before the 21st century? I mean, sure, it’s pretty clear that it was autocephalous after the Third Ecumenical Council, but by the time we reach the modern period, it’s just as clear that the Church of Cyprus was not able to manage its own internal affairs without the involvement of other churches – meaning it lacked one of the signature traits of an autocephalous church. If there was a church crisis, Cyprus had to bring in outside help. If that’s only changed in the 21st century, we have to consider the possibility that the modern iteration of the Church of Cyprus as an autocephalous church dates, not to 431, but sometime in the past fifteen years.

Georgia

The Apostle Andrew was arguably the most widely-traveled of the Twelve Apostles, and as with Romania (and Russia, and Constantinople, etc.), according to tradition, he was the first to preach the Gospel in what is now Georgia. In the fourth century, the Most Holy Theotokos herself sent St Nino to evangelize Georgia, making it the only nation whose primary evangelist was a woman. In these early years, the Church of Georgia was under the authority of the Patriarchate of Antioch. In the second half of the fifth century, Georgia is said to have become “autocephalous,” but in practice this appears to be what we now call “autonomy” – the primate was confirmed by Antioch, but he could appoint local bishops without outside involvement. Georgian ecclesiastical independence was a contested point for hundreds of years, but by the 11th century, the Church of Georgia was recognized by everyone as autocephalous. Its primate had the title “Catholicos-Patriarch.”

In 1801, the Russian Empire annexed Georgia, and ten years later, it forcibly abolished the Georgian Orthodox Church, removing the native Catholicos-Patriarch and subordinating the Georgian people to Russian bishops. This began a dark era of inter-Orthodox oppression and persecution, as the Russian church and state attempted to stamp out any vestiges of indigenous Georgian Orthodoxy. This ultimately failed, and in the early 20th century, a movement began for the restoration of Georgian autocephaly. After the fall of the Tsar in 1917, Georgian church leaders held a council, restoring the Georgian Church and electing a new Catholicos-Patriarch. The Russian Church condemned the action. Soon, the Soviets took over Georgia, and the church was harshly suppressed again. But it survived, and in 1943, the Moscow Patriarchate issued a Tomos of Autocephaly.

This was initially not recognized by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In the 1960s, the Orthodox Churches met several times to prepare for a Pan-Orthodox Council. The EP insisted on treating Georgia as an autonomous church under Moscow rather than as autocephalous. This frustrated the Georgians, and the impasse continued until 1990, when the Soviet Union was in the process of collapse. The EP and the Georgian Church entered into negotiations, with the sticking point being whether the EP was granting autocephaly or simply recognizing Georgia’s already-existing and ancient autocephaly. In the end, the EP issued a carefully-worded Tomos granting its “recognition” and “official approbation” – that is, Georgia had long been an autocephalous church, and the EP accepted this. The EP also accepted that Georgia would continue its ancient practice of consecrating its own Holy Chrism.

Georgia’s Tomos from the EP dates only to 1990, and as a result, the EP and numerous other Churches rank Georgia lower in the diptychs than Serbia, Romania, and Bulgaria, who received tomoses from the EP before Georgia did. However, according to the diptychs of the Moscow Patriarchate and some others (e.g., the OCA), Georgia ranks above those three patriarchates, since the origins of its autocephaly precedes them. In any case, since 1990, Georgia has been universally recognized as autocephlous.

Bulgaria

At various points in history, Bulgaria had an autocephalous church (often, but not always, called a patriarchate), and at various points, that church was suppressed. The most recent such suppression was in 1767, when the Ottoman Empire suppressed the Archbishopric of Ohrid and subordinated the Bulgarian churches to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. This situation continued for another century, and the Bulgarians became increasingly hostile to being controlled by a Greek-speaking hierarchy based in Constantinople. In 1870, the Ottoman government created an independent Bulgarian church, the “Bulgarian Exarchate,” with the innovative provision that any province with a critical mass of Bulgarians could vote to switch its jurisdiction from the Ecumenical Patriarchate to the Exarchate. In 1872, a council in Constantinople condemned this ethnicity-based model of church governance as “ethnophyletism.” The same council anathematized the Bulgarian bishops and their followers.

Not everyone recognized the council’s decisions. In particular, the Russian and Romanian churches would provide the Bulgarians with Holy Chrism in the intervening decades. In 1945, the Moscow Patriarchate facilitated a reconciliation between the Bulgarian Exarchate and the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and after nearly three-quarters of a century, the “Bulgarian Schism” was healed, and Bulgaria’s autocephaly was recognized by all. In 1953, the Bulgarian Church elected a new primate and gave him the title “Patriarch,” thereby restoring the Bulgarian Patriarchate. The only churches that recognized this new patriarchal status were Antioch, Moscow, and the other churches behind the Iron Curtain. The EP condemned Bulgaria’s unilateral action, but by the early 1960s, the EP and the other churches all accepted the elevation of the Bulgarian Church to a Patriarchate.

Romania

The Apostle Andrew is traditionally regarded as the founder of Orthodoxy in Romania. In the 19th century, Romanians were divided into various regions – in territories variously controlled by the Ottoman, Russian, and Habsburg Empires. The principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia changed hands between the Ottomans and the Russians, and for the most part, until 1818, the Orthodox Church in these lands consisted of an ethnically Romanian flock ruled over by Greek bishops. After 1818, Romanian bishops became the norm. In the 1850s, Wallachia and Moldavia were united under a single ruler, Prince Cuza, and became known as “Romania.” In 1864, Cuza issued a law declaring the church in his domains to be independent, and the following year, a primate was elected. This was basically comparable to the situation in Greece three decades earlier – a domineering ruler declaring his church to be autocephalous as a way to assert greater control over it. It’s notable that in the cases of both Greece and Romania, the ruler who declared autocephaly also simultaneously perpetrated the confiscation of monastic estates and placed heavy restrictions on the monastic life. The EP rejected Romania’s claim to autocephaly, but this was basically ignored, and in 1882 the Holy Synod of Romania consecrated Holy Chrism for the first time. Finally, in 1885, the EP accepted the fait accompli and issued a Tomos of Autocephaly.

That’s just one part of the story, though. In addition to “Romania” (i.e., Wallachia and Moldavia), there were other Romanian Churches. In 1864, the same year Cuza declared autocephaly for the church in his territory, the Romanian Orthodox Church of Transylvania declared its own independence, having been suppressed by the Hapsburgs since 1701. Transylvania, which was in the Habsburg Empire, had been part of the Serbian Patriarchate of Karlovci, which itself had been re-established fairly recently, in 1848. Then, in 1873, the multiethnic region of Bukovina, also in the Habsburg Empire, broke away from the EP. Meanwhile, the ethnically Romanian region of Bessarabia, which had been part of the Ottoman principality of Moldavia until the early 19th century, came under Russian control in 1812. It was governed by an exarch appointed by the Holy Synod of Russia for the next century.

In 1919, as part of a series of postwar treaties, the Romanian state was united with Transylvania, Bessarabia, and Bukovina, to form Greater Romania. The Romanian Orthodox bishops in all these lands united in a single Romanian Orthodox Church and elected Metropolitan Miron of Transylvania as their primate. In 1925, the Holy Synod decided to elevate Metropolitan Miron to the rank of Patriarch. Unlike the Bulgarian patriarchal elevation in 1953, this decision wasn’t really opposed by the EP, which, at the time, was in such a state of crisis that it wasn’t really in a position to object.

Serbia

A few years ago, the Serbian Church celebrated the 800th anniversary of its autocephaly, dating back to St Sava, the great father of an independent Serbian Church. This church was ultimately elevated to the status of patriarchate (the Patriarchate of Pec), which lasted until 1766, when it was suppressed by the Ottoman Empire and its territories were given to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Up to that time, the prince-bishops of Montenegro (an unusual kind of theocratic arrangement, with the office passing from uncle to nephew) were functionally independent, but were typically consecrated by bishops from the Patriarchate of Pec. After Pec was suppressed, the Montenegrin bishops assumed the title, “Exarch of the Throne of Pec.”

At the end of the 17th century, the Habsburg Emperor established the Metropolitanate of Karlovci, an autocephalous church for all Orthodox Christians in his empire. This church had a multiethnic flock (mostly Serbs and Romanians, as well as some Greeks), but the hierarchy was dominated by Serbs. The Roman Catholic emperor had wide authority, much like his Ottoman Muslim counterpart in relation to the Ecumenical Patriarchate: the emperor had to approve all hierarchical nominations, and the church was heavily regulated by the state. As with Greece, autocephaly was used by the state as a tool to enhance government control over the church within its borders. In 1848, following the Hungarian Revolution, the Serbs in Hungary held a national assembly and elevated Karlovci to the status of a patriarchate.

Montenegro and Karlovci were far from the only Serbian churches in this era. In 1830, the Prince of Serbia, who was nominally subject to the Ottoman Empire, set up an autonomous Metropolitanate, based in Belgrade, with a metropolitan and three other bishops. A year later, the Ecumenical Patriarchate agreed to the arrangement, retaining the right to confirm hierarchical elections. Belgrade’s Greek-speaking metropolitan stepped aside to allow the election of a native-born Serb. Later, in 1879, the Prince of Serbia and the Metropolitan of Belgrade formally requested and received a Tomos of Autocephaly from the EP. But in 1881, the prince had a dispute with the hierarchy, dismissing the primate and dissolving the bishops’ council. The next Metropolitan of Belgrade had to be consecrated by bishops from the Patriarchate of Karlovci, which amounted to a temporary abrogation of Serbia’s brand-new claim to autocephaly.

By the late 19th century, the Patriarchate of Karlovci wasn’t even the only Serbian Orthodox Church in the Habsburg Empire. In 1878, the Habsburgs assumed de facto control over Bosnia and Herzegovina, which up to that point had been under the Ottoman Empire. This raised the question of ecclesiastical jurisdiction, since the EP continued to claim these territories. The EP and the Habsburg Empire entered into negotiations, and finally, in 1883, they signed an agreement to create what amounted to an “autonomous” church of Bosnia and Herzegovina. The bishops of this church would be appointed by the (Roman Catholic) Habsburg Emperor, subject to confirmation by the EP, which would also provide Holy Chrism and continue to be commemorated liturgically.

These aren’t even all of the churches with large Serbian Orthodox populations – I haven’t even mentioned places like Kosovo and Skopje. In 1918, the various Serbian territories united politically, forming what became known as Yugoslavia. Two years later, the various Orthodox Churches in the new country unified, forming the modern-day Serbian Patriarchate. The Serbian Patriarch lives in Belgrade but holds the title “Patriarch of Pec,” linking him to the original independent Serbian Church founded by St Sava.

Russia

The Russian Orthodox Church is a great example of the difference between a church and the governing structure of that church. According to tradition, the Apostle Andrew first brought Christianity to the land that would become known as Rus’. That said, it wasn’t until the tenth century that the Church arrived in the region at any kind of scale. Famously, St Vladimir, the Grand Prince of Kiev, invited missionaries from Constantinople to evangelize his people in 988. This became known as the Baptism of Rus’ and is the origin point for the Orthodox Churches in modern-day Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. The original structure of the new church was as a metropolis under the Ecumenical Patriarchate – the Metropolis of Kiev. By the 13th century, the city of Kiev had declined, and its status as the leading city of Rus’ was ultimately overtaken by Moscow, although the metropolitan in Moscow initially continued to use the old title “of Kiev.” (For years, there were actually two metropolitans who claimed the title “of Kiev,” both under Constantinople. But that’s a story unto itself.)

Things changed in the 15th century, when most of the bishops of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, including the EP-appointed Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev, entered into union with the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Florence. When Isidore returned to Kiev, his people rejected him and he fled to the West. In 1448, the Russian bishops then elevated one of their own, Jonah, to become their new primate. This was done without the consent of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which at the time had abandoned Orthodoxy in favor of the Unia. The elevation of Jonah to the rank of Metropolitan is viewed by the Russian Church as the moment of its autocephaly. The Ecumenical Patriarchate returned to Orthodoxy at the time of the Ottoman conquest in 1453, but the church in Moscow remained independent. In 1589, the Ecumenical Patriarchate finally accepted this new reality, not only recognizing Moscow as autocephalous, but elevating its primate to the status of Patriarch. By 1591, this had been ratified by the other patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The new Patriarchate of Moscow lasted for just over a century. In 1700, the Patriarch died, and Tsar Peter the Great refused to allow the election of a successor. The Patriarchate was led by a locum tenens until 1721, when the Tsar formally abolished it and replaced it with an entirely new structure: a Holy Synod coordinated by a lay government official known as the “chief procurator.” This framework was modeled on the arrangements of the Lutheran Church in Sweden and Prussia. The new Synodal system lasted for nearly two centuries – longer than the original Patriarchate – until the fall of the Tsar in 1917.

After the February Revolution of 1917, the new Provisional Government in Russia authorized the convening of an All-Russian Council, which reorganized the Russian Orthodox Church and reestablished the Patriarchate of Moscow, electing St Tikhon as the first Patriarch. As the council was taking place, the October Revolution occurred, bringing the Bolsheviks into power. Under the new Communist regime, the Russian Church was harshly persecuted, and normal church administration was impossible. St Tikhon died in 1925, and it was impossible to hold a normal patriarchal election. Instead, in a very unusual ad hoc sort of arrangement, St Tikhon appointed three potential successors in his will, who could become locum tenens if necessary. Soon after Tikhon’s death, his appointed locum tenens was himself imprisoned, but he had drawn up his own list of potential successors. This left the Patriarchate nominally in the hands of Metropolitan Sergius Stragorodsky. On paper, the Moscow Patriarchate continued to exist, but in practice, it could not actually govern the Orthodox Church in what was now the Soviet Union. It basically had no functioning institutions. Its theological schools had long since been closed, and normal processes like councils and hierarchical elections couldn’t happen. Metropolitan Sergius hung onto the title locum tenens for years, but it was not a title that carried a lot of real-world authority.

That all changed during World War II. The war led Soviet dictator Josef Stalin to reestablish the Moscow Patriarchate. In 1943, he allowed for a new patriarchal election to take place, along with the opening of theological schools and the printing of church materials. The Moscow Patriarchate was reborn, and Metropolitan Sergius was elected Patriarch. This, more so than 1917, really marks the beginning of the present-day Moscow Patriarchate as a functioning institution governing the entire Russian Orthodox Church.

Throughout all these changes, the Russian Orthodox Church has never ceased to exist, but the government of that Church has changed in dramatic ways. 988, 1448, 1589-91, 1721, 1917, 1943 – all of these are key inflection points, when the government of the Russian Church changed its form. The Russian Church formally originated in 988, but the present-day Moscow Patriarchate was really born in 1943.

Jerusalem

The Patriarchate of Jerusalem is sometimes referred to as the “Mother of the Churches,” and it makes sense – it was, of course, in Jerusalem that the Holy Spirit descended on the day of Pentecost, and it was from Jerusalem that the Apostles spread the Gospel throughout the world. But the city of Jerusalem was razed to the ground by the Roman Army following the revolt in AD 70 and the Bar Kochba rebellion in the 130s, and the Romans built a new city on top of the ruins, known as Aelia Capitolina. Although the city continued to have a Christian presence with a local bishop, this was now a very minor see. In time, the church of Aelia Capitolina became subordinate to the Metropolitan of Caesarea, which was the major city in Palestine.

In the fourth century, after St Constantine the Great became a follower of Christ, his mother St Helen traveled to Aelia and found the True Cross. She funded the construction of churches, and Jerusalem was reborn as a new city of Christian pilgrimage. Canon 7 of the First Ecumenical Council gave special honor to the city while preserving the privileges of the Metropolitan of Palestine, whose seat was Caesarea: “Inasmuch as a custom has prevailed, and an ancient tradition, for the Bishop of Aelia [Jerusalem] to be honored, let him have the sequence of honor, with the Metropolitan [of Caesarea] having his own dignity preserved.”

This created something of an awkward arrangement, with the bishop of Jerusalem holding a very high position of honor without actual authority – in his region, the bishops of Caesarea and Antioch exercised the greatest authority. This persisted until 451, when the Fourth Ecumenical Council issued a decree establishing the jurisdiction of both Antioch and Jerusalem, and Jerusalem as primary in its own region: “… the most holy bishop Maximus, or rather the most holy church of Antioch, shall have under its own jurisdiction the two Phœnicias and Arabia; but the most holy Juvenal, bishop of Jerusalem, or rather the most holy Church which is under him, shall have under his own power the three Palestines, all imperial pragmatics and letters and penalties being done away according to the bidding of our most sacred and pious prince.” Another century later, in the time of the Emperor Justinian, the title “Patriarch” came to be applied to the bishops of the four great Roman cities – Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch – as well as the highly-honored Jerusalem. The prominence of these five sees became known as the “pentarchy” – the “rule of five.”

Jerusalem’s fortunes declined over the next millennium. The Holy Land was perhaps the most contested piece of real estate in the world, fought over amongst Romans, Arabs, Crusaders, and Turks. From the defeat of the Crusaders in Jerusalem until 1534, all of the Patriarchs of Jerusalem were elected from among the indigenous Arabic-speaking Orthodox people. In that year, an ethnic Greek, Germanus, became Patriarch. He held the office for three decades, and over time he gradually replaced the indigenous bishops with fellow Greeks. He formed the Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre, a Greek-only monastic community. The members of the Holy Synod of Jerusalem were – and are – drawn exclusively from the membership of the Brotherhood. Thus the Brotherhood came to function as a sort of church-within-a-church for Jerusalem, with its membership restricted to Greeks and excluding the indigenous Arabic-speaking Orthodox faithful. This remains true to this day.

From the fall of the Byzantine Empire until the 17th century, it was customary for the Patriarch of Jerusalem to appoint his own successor, usually by making the chosen heir the Metropolitan of Caesarea. This practice continued for a time after 1534, but things changed in 1669, when the Holy Synod of Constantinople stepped in to elect a new Patriarch of Jerusalem. This marked the beginning of a new era for the Patriarchate of Jerusalem, in which successive Patriarchs were chosen by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Despite their title, the Patriarchs of Jerusalem lived year-round in Constantinople, ruling their church from afar. For all practical purposes, Jerusalem was now an autonomous church under Constantinople.

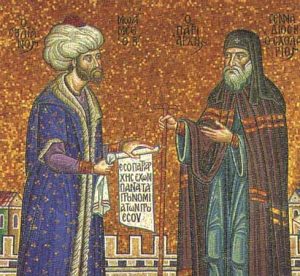

In 1845, the Holy Synod took the momentous step of once again electing its own Patriarch, without involvement of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In time, that patriarch, Cyril II, moved the patriarchal residence back to Jerusalem. Thus the modern-day Patriarchate of Jerusalem can very reasonably be dated to Cyril’s election in 1845, despite the great antiquity of the Church of Jerusalem.

Antioch

Like Jerusalem, the Church of Antioch features prominently in the Book of Acts. Its first bishop was the Apostle Peter, and it was one of the great cities of the Roman Empire. As the “metropolitan” system emerged in the early centuries of the Church – with bishops of major cities presiding over regularly-convened synods of regional bishops – Antioch was a leading see. Canon 6 of the First Ecumencial Council confirmed Antioch’s long-standing preeminence, along with that of Rome and Alexandria: “Let the ancient customs prevail which were in vogue in Egypt and Libya and Pentapolis, to allow the bishop of Alexandria to have authority over all these parts, since this is also the treatment usually accorded to the bishop of Rome. Likewise with reference to Antioch, and in other provinces, let the seniority be preserved to the Churches…” This was further clarified in Canon 2 of the Second Ecumenical Council.

Antioch was one of the Pentarchy that emerged in the coming centuries, but in time, as the region was conquered by a succession of invaders, Antioch’s fortunes declined. For long periods, the Patriarchs of Antioch lived in Constantinople. One famous example was Theodore Balsamon, who is famous as a canonist but was elected Patriarch of Antioch despite never setting foot in Syria. The ancient city of Antioch itself continued to decline, and in the 14th century, the actual seat of the Patriarchate was moved to Damascus, effectively merging the sees of Antioch and Damascus. The city of Antioch is now called Antakya and is in modern-day Turkey. It’s a somewhat little-known fact that the Patriarchate of Antioch continues to have jurisdiction over territory in Turkey, including Antakya.

From 1250 until the early 16th century, the Mamluk Empire ruled Syria and Egypt. This ended with the Ottoman conquest of these regions in 1516-17, which brought the four remaining members of the Pentarchy (minus Rome, of course) under a single civil authority for the first time in some nine centuries. Antioch soon felt the effects of this new reality. In 1543, Patriarch Dorotheus III of Antioch was deposed by a synod that was presided over by the Patriarchs of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Jerusalem. In the 18th century, the Patriarchate of Antioch became a battleground between Orthodoxy and the forces of Uniatism, which sought to place Antioch under the control of the Pope of Rome. In 1724, Patriarch Athanasius Dabbas died, and the people of Damascus elected a pro-Uniate patriarch as his successor. The Antiochian Holy Synod rejected this. The alternative candidate Patriarch Athanasius’s deacon, Sylvester, who had a foot in both the Greek and Syrian worlds: he had been born on Cyprus and lived as a monk on Mount Athos, but his mother was Syrian and he spoke Arabic. Thanks to the intervention of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, Sylvester became Patriarch of Antioch. Sylvester was Patriarch for a remarkable forty-two years, and during his reign, Greek influence in the Patriarchate of Antioch grew. After Sylvester, the Patriarchate was controlled by ethnic Greeks until the end of the 19th century. This period is known to Antiochians as the “Greek captivity of Antioch,” and it became a source of immense frustration for the indigenous Syrians, but at its inception, it might reasonably be viewed as a last-ditch effort to save Antioch from heresy.

The Patriarchate of Antioch was under ethnically Greek control from 1724 until the very end of the 19th century. In the 19th century, the Patriarchate came under the control of Jerusalem’s Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre. During this period, the Patriarchs of Antioch were all members of the Brotherhood. As the 19th century wore on, the indigenous Syrians chafed under the rule of what they viewed to be Greek interlopers. In 1898, the Syrian bishops of Antioch, which constituted a majority of the Holy Synod, deposed their Greek Patriarch, and the following year they elected Meletius Doumani as the new Patriarch – the first native Syrian to hold the see of Antioch in 175 years. Patriarch Meletius’s election in 1899 can reasonably be viewed as the beginning of the modern governing structure of the Patriarchate of Antioch.

As recently as the 17th century, Antioch consecrated its own Holy Chrism, but in recent centuries it, along with Jerusalem and Alexandria, has received Holy Chrism from the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Alexandria

According to tradition, the see of Alexandria was founded by the Apostle and Evangelist Mark. Along with Rome and Antioch, it was one of the leading sees in Christianity in the early centuries of the Church, and its high status was confirmed in Canon 6 of the First Ecumenical Council and Canon 2 of the Second (quoted above). The Alexandrian Church was torn apart by the Monophysite schism, and in time, its territory was conquered by Arab invaders. Like Syria, Egypt was ruled by the Mamluks until the 16th century, when it was conquered by the Ottomans. By this time, the Church of Alexandria had dwindled to a faint shadow of its former glory. For centuries, despite being called a patriarchate, it was effectively a single diocese with one ruling bishop (the Patriarch) and a few titular bishops, all of whom were Greek speakers ruling over an Arabic-speaking flock.

The Alexandrian situation resembles that of Jerusalem: the Patriarch came to live in Constantinople and the Ecumenical Patriarchate routinely intervened in Alexandria’s internal affairs. In 1825, the EP deposed Patriarch Theophilos II of Alexandria. In 1845, at the same time Jerusalem was reasserting its independence from Constantinople, the Alexandrian throne became vacant, and the EP Holy Synod attempted to elect a new Patriarch. This time, the local Egyptian flock protested, leading to a two-year battle that culminated in the Egyptian government arranging for a local patriarchal election and, critically, the transfer of the patriarchal residence back to Egypt. In the 1860s, Alexandria established its first Holy Synod in modern history. Despite this, the Ecumencial Patriarchate continued to intervene in Alexandrian patriarchal elections, and in 1889, the entire episcopate of Alexandria had dwindled to a single man – the Patriarch himself. He had a title, but for all practical purposes, he was basically a sort of autonomous diocesan bishop.

At the literal turn of the 20th century (December 29, 1899 on the Julian Calendar, January 10, 1900 on the Gregorian), Alexandria elected Photios Peroglou as its new Patriarch. Photios quickly set about securing Alexandria’s independence: he re-established old Alexandrian dioceses, consecrated new bishops, and ensured that the Patriarchate would no longer be subjected to outside intervention. Under Photios’s successor, Patriarch Meletius Metaxakis (who had previously been Ecumenical Patriarch), Alexandria began to expand its jurisdiction beyond its traditional territory, claiming the title “All Africa.”

Although Alexandria continues to receive Holy Chrism from Constantinople, it now has dozens of bishops, a fully functioning Holy Synod, and the capacity to manage its own internal affairs. This is a far cry from the 19th century and before. Thus the real birth of the modern Alexandrian Patriarchate can be dated to sometime after Photios’s election in 1899/1900.

Constantinople

The Ecumenical Patriarchate considers its founder and patron to be the Apostle Andrew, who, it is said, installed St Stachys as the first Bishop of Byzantium in the first century. In the early centuries of the Church, the bishops of Byzantium were subject to the Metropolitan of Heraclea. Under St Constantine the Great, the relatively minor city of Byzantium was transformed into Constantinople – New Rome, the capital of the Roman Empire. In response to this new reality, Canon 3 of the Second Ecumenical Council (381) declared, “Let the Bishop of Constantinople, however, have the priorities of honor after the Bishop of Rome, because of its being New Rome.” Then, in 451, the Fourth Ecumenical Council produced the famous and controversial Canon 28 of Chalcedon, which expanded the authority of the Bishop of Constantinople based on the rationale “that the city which is the seat of an empire, and of a senate, and is equal to old imperial Rome in respect of other privileges and priorities, should be magnified also as she is in respect of ecclesiastical affairs, as coming next after her, or as being second to her.” This canon subordinated the Metropolitans of Pontus, Asia, and Thrace (although not the diocesan bishops in these provinces) to the Bishop of Constantinople. The canon also gave to Constantinople responsibility over “the Bishops of the aforesaid dioceses which are situated in barbarian lands.”

It’s clear, then, that by 381 and certainly 451, the institution that would become known as the Patriarchate of Constantinople held an extremely high position in the Christian world. The role of this institution evolved over time. Eventually, the Patriarch of Constantinople began using the title “Ecumenical Patriarch.” At various times, the Patriarchate fell into heresy (different Christological heresies, Iconoclasm, and Uniatism), but, sooner or later, the Orthodox recovered control over it each time. At the turn of the second millennium, the model of an “endemousa synod” emerged: a gathering of bishops who happened to be in Constantinople at a given time, to deal with situations that arose. In the 1440s, the Patriarchate surrendered itself to the Roman Catholic Church, but at the time of the Ottoman conquest of Constantinople in 1453, it returned to Orthodoxy. The first Ecumenical Patriarch after the conquest was Gennadios Scholarios, a friend of St Mark of Ephesus and a firm opponent of the Unia.

This moment, 1453, marks the beginning of a new era in the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Throughout the 20th century, it was common to hear that after 1453, the Ecumenical Patriarch became, not only the leader of the Orthodox in the Patriarchate of Constantinople, but the head (“milletbasi”) of the “Rum millet,” which encompassed all Orthodox Christians in the Ottoman Empire, including those under other autocephalous churches. This story has been somewhat debunked in recent years: in fact, the situation was much more complex and fluid, and the Rum millet / milletbasi model and terminology emerged over time, not taking its final form until the 18th century.

At the top, there was an immense amount of instability during the Ottoman period: the Patriarchal office was effectively auctioned off by the Ottoman government to the highest bidder, and the Patriarch and other bishops functioned as tax farmers for their Ottoman overlords. The turnover of the position of Ecumenical Patriarch is almost unfathomable: from the Ottoman conquest in 1453 until the end of World War I in 1918 (marking the de facto end of Ottoman rule, although the position of Sultan wasn’t abolished until 1922), the Patriarchal title changed hands 166 times – an average of just 2.8 years per patriarchal tenure. Many Patriarchs held the position on multiple occasions; for example, Cyril Lucaris was Patriarch six times between 1620 and 1638 (plus another term as locum tenens in 1612). The Sultan had the power to remove Patriarchs at will, and his consent was required for any Patriarch (or bishop, for that matter) to take office.

In 1741, reforms were introduced into the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which came to be governed by a synod of senior metropolitans. This system was known as “gerontism” and remained in place for more than a century, until it was replaced during the Tanzimat Reform period following the Crimean War in the 1850s. This ushered in a new era for the Patriarchate, which would now be governed in part by a mixed council that included clergy and lay representatives. Far from an artifact of antiquity, the governing structure of the EP changed in dramatic ways over time.

At the end of World War I, an Allied coalition led by the British and French occupied Constantinople. From 1918 to 1921, the patriarchal throne was vacant, and the Patriarchate was led by a locum tenens. This man died in 1921, and a new election was finally held. Sixty-eight metropolitans were eligible to vote, but just thirteen of them were present for the election. Another five voted by proxy. Meletios Metaxakis, the exiled ex-Metropolitan of Athens, was elected with sixteen out of eighteen votes.

In Meletios’s brief tenure – less than two years – the very identity of the Ecumenical Patriarchate changed in fundamental ways. The Ottoman Empire was formally abolished, replaced by the secular Republic of Turkey, and with this change, the EP’s self-understanding as civil head of the Rum millet in the Ottoman Empire was also wiped out. The Greco-Turkish War ended in catastrophe for the Greeks, leading to the burning of the largely Greek city of Smyrna and the massacre of thousands of Orthodox Christians. Most traumatically, the Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the Greco-Turkish War, mandated a “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey. Millions of Orthodox Christians were forcibly deported from their ancient homeland in Asia Minor and resettled in Greece. (A smaller but still significant number of Muslims were forced to move from Greece to Turkey.) Overnight, the Ecumenical Patriarchate was depopulated, going from a lively church with millions of faithful in dioceses that had existed from antiquity, to a shell with a hundred thousand or so parishioners limited to the city of Constantinople itself.

Under these difficult circumstances, the Patriarchate reinvented itself. Patriarch Meletios was a creative and ambitious man, and he formulated a new interpretation of Canon 28 of Chalcedon. As discussed above, Canon 28 gave to Constantinople responsibility the right to ordain the metropolitans (but not the other bishops) of the Roman provinces of Pontus, Asia, and Thrace, as well as “the Bishops of the aforesaid dioceses which are situated in barbarian lands.” Faced with the loss of nearly all of the EP’s flock, Meletios pivoted, reinterpreting Canon 28 by essentially ignoring the words “of the aforesaid dioceses” and asserting that the phrase “barbarian lands” meant that the EP has jurisdiction over all territories anywhere on earth that are not already part of another Orthodox Church. In one sweep, Meletios attempted to expand the EP’s rapidly-shrinking canonical territory to encompass the entire Western Hemisphere, as well as Australia and much of Asia, among other places. If the Patriarchate could no longer be the head of all Orthodox in the Ottoman Empire, it would now become a transnational institution, the coordinating body of global Orthodoxy.

In July 1923 – the month after Meletios hosted a Pan-Orthodox Congress that endorsed the New Calendar, and days after he received the Churches of Finland and Estonia (formerly part of the Russian Church) into the jurisdiction of the EP – Meletios fled Turkey aboard a British steamship. In October, the Republic of Turkey was created. On October 2, 1923, literally as the Allied evacuation of Constantinople was taking place, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was meeting at the Phanar (the headquarters of the EP). Papa Efthim, leader of the schismatic “Turkish Orthodox Church,” burst into the room with a guard of Turkish police. He ordered the Holy Synod to declare Patriarch Meletios to be deposed within ten minutes. The Holy Synod complied. Then the Turkish police expelled six of the eight Holy Synod members, along with the Locum Tenens, from the building. (All of the expelled bishops had sees outside of Turkey.) Papa Efthim then replaced the seven expelled bishops with his own partisans. At that moment, it appeared that the Ecumenical Patriarchate either no longer existed, or had just been taken over by a coup d’etat. Meletios, who was in Greece, ultimately accepted that he could not remain Patriarch, but he backdated his resignation in an attempt to undercut the actions of Papa Efthim.

In November 1923, the Holy Synod of Constantinople elected Gregory VII as the next Patriarch. He ruled for a mere eleven months before dying of a heart attack. The top contender to replace him was Metropolitan Constantine of Derkos. This was a problem, because Constantine had only moved to Istanbul in 1921, and the Lausanne Treaty provided that the only Greeks who were exempt from deportation were those who resided in Istanbul as of October 1918. Constantine, then, was “non-exempt,” subject to deportation. The Turks briefly arrested Constantine and two other candidates, and the Greek consul in Istanbul begged the Holy Synod to postpone the election. But they refused, and the next day, Constantine was elected Ecumenical Patriarch. The Turks insisted that Constantine was still going to be deported.

An international “mixed commission” had been set up to oversee implementation of the Lausanne Treaty, and the Greek representatives tried to appeal to this commission on behalf of the Patriarch. But the commission’s hands were tied – the deportation provisions of the Lausanne Treaty made no exceptions for church leaders, so the Patriarch was to be treated no differently than any other Greek. At around midnight on January 30, 1925, the Ankara-based Turkish government sent a cipher telegram to Istanbul, ordering the expulsion of Patriarch Constantine from the country. At 6:30 in the morning, the Patriarch was confronted by the Assistant Director of Police, who took him to a railroad station and put him on a train to Greece. Rumors swirled that more Orthodox bishops would be deported in the coming days. Greece responded by severing diplomatic ties with Turkey and appealing to the League of Nations.

Constantine had been Ecumenical Patriarch for about two months when he was deported, and it was not at all clear whether Turkey would allow for the election of a new patriarch. The Archbishop of Athens was indignant – he said that the Patriarch’s expulsion was “much more serious than even the hanging of Patriarch Gregory V in 1821, because its object is not only to terrify the Greeks, but to accomplish a plan for uprooting the Patriarchate.” The Turks and the Greeks and the remaining Holy Synod members in Istanbul were negotiating next steps, but then the exiled Patriarch Constantine threw a monkey wrench in March when he refused to abdicate. Both Constantine and his predecessor Meletios, along with a sizable number of metropolitans, proposed transferring the Patriarchate to Mount Athos and appointing an archbishop to the Phanar in Istanbul.

But, counterintuitively, the Turks weren’t all-in on expelling the Patriarchate itself. The British ambassador to Turkey explained, “It has been realised that its continuance here may provide Turkish policy with certain levers which could be lost if the institution was completely suppressed. The present intention of Angora [Ankara] is, therefore, to keep the Patriarchate here, but in such a reduced state that it would be a mockery of its former self and a ready tool in Turkish hands.” This is the Turkish position that ultimately won out, and the Ecumenical Patriarchate has remained in Istanbul to this day. By Turkish decree, candidates for Patriarch must be citizens of Turkey, and the Turkish Governor of Istanbul has the right to veto any candidate for any reason.

The period from 1922 to 1925, then, represents a major inflection point in the history of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. By 1925, the institution of the Patriarchate was virtually unrecognizable compared to its pre-World War I manifestation. The bridge figure here is Meletios Metaxakis: the Patriarch of the Allied Occupation, the final Ottoman Patriarch and the first Turkish Patriarch, the last Patriarch to oversee an indigenous flock and the originator of the EP’s modern transnational identity.

***

Here, then, is a timeline of when the fourteen universally-recognized autocephalous churches came into being in their modern form:

1845 Jerusalem

1850 Greece

1899 Antioch

1900 Alexandria

1919 Romania

1920 Serbia

1922-25 Constantinople

1924 Poland

1943 Moscow and Georgia

1945 Bulgaria

1951 Czech Lands & Slovakia

1992 Albania

After 2006 Cyprus

I realize that this might seem absurd, or even perhaps offensive, to some. How can I say that none of the world’s Orthodox Churches existed before 1845? How can I claim that Ecumenical Patriarchate is barely a century old? Here, it’s important to disambiguate, firstly between a Church and the governing structure of that Church. As I said above when discussing Russia, it’s obviously true that the Russian Orthodox Church is a millennium old, but it’s just as obviously true that the Moscow Patriarchate in its current form was born in September of 1943, with the permission of Josef Stalin. Nominally, sure, you can push the start date back to 1917, but as an institution, it’s pretty clear that 1943 is when the current form was attained. Before 1917, the governing structure of the Russian Orthodox Church was radically different – no Patriarch, a Holy Synod without a primate, and a government-appointed procurator who wielded considerable authority.

We can do the same sort of analysis with the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The institution very clearly changed in massive ways after the Ottoman conquest in 1453, and it also changed significantly at other points, such as 1741 (the institution of “gerontism”) and the 1850s Tanzimat era (with the advent of the mixed council). These aren’t small changes, adjustments around the edges – they’re ecclesiastical earthquakes. The 1920s is an even bigger earthquake, such that the pre- and post-Meletios Ecumencial Patriarchates bear very little resemblance to each other. The name is the same, but the institution is not.

What does this mean for us today? It means that, in many respects, we are a Church with amnesia. We remember Nicaea and Chalcedon like they happened yesterday, but we have very little understanding of the 19th and 20th centuries, like a middle-aged man who remembers his childhood but nothing after he became a teenager. We’ve awakened from a stupor to find ourselves in an unfamiliar and deeply distressing reality, and without understanding how we got here, we can’t even comprehend ourselves, the feelings and struggles we experience, much less discern any way forward. We as a Church need to come to terms with the stark and painful and sometimes embarrassing reality of our recent past if we ever hope to find solutions to our current crises and chart a course for the future.

Leave a Reply