This paper was originally presented at the conference “The Greek Archdiocese at 100 Years,” Hellenic College-Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, October 7, 2022. I am indebted to numerous friends and colleagues who reviewed the paper in advance and provided feedback. I am especially grateful to M., who provided original translations of the 1908 and 1922 documents, as well as to canonists Fr Patrick Viscuso and Fr John Erickson. Click here to view the original conference presentation (along with brief Q&A) on YouTube.

The Origins of the ‘Barbarian Lands’ Theory

The Greek Archdiocese of America and the Interpretation of Canon 28 of Chalcedon

By Matthew Namee

In 1924, the future Patriarch Christophoros of Alexandria, then Metropolitan of Leontopolis, published an article called “The Position of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the Orthodox Church.”[1] Christophoros opens by explaining the reason for his study: “the tendency that the Ecumenical Patriarchate has had over the past two years to desire to extend its spiritual jurisdiction over every ecclesiastical territory or every community which, for one reason or another, was or appeared to be deprived of regular spiritual government and oversight, which one describes as ‘Churches of the Diaspora.’” Christophoros presents this as something novel, something that has emerged “over the past two years” – that is, since 1922.

***

One of the keystone prerogatives claimed by the Ecumenical Patriarchate is its jurisdiction over the so-called “diaspora” – regions not included within the geographic boundaries of the other Autocephalous Churches. Many Churches don’t accept this claim, evidenced by the presence of Antiochian, Russian, Serbian, Romanian, Bulgarian, and Georgian jurisdictions here in the United States and elsewhere in the diaspora. But the Ecumenical Patriarchate insists that this exclusive extraterritorial jurisdiction is in fact ancient, rooted in Canon 28 of Chalcedon, the Fourth Ecumenical Council, in the year 451.

Canon 28 is a fascinating text. First, it acknowledges that the Bishop of Constantinople now has privileges equal to the Bishop of Rome, due to the fact that Constantinople is now the imperial capital and the seat of the senate. In the second half of the canon, it declares,

[O]nly the metropolitans of the Pontian, Asian, and Thracian dioceses, as well as the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses among barbarians are ordained by the aforementioned most holy throne of the most Holy Church of Constantinople.[2]

This phrase – “the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses among barbarians” – is central to the Ecumenical Patriarchate’s canonical claim to exclusive jurisdiction in the “diaspora.”

In 2009, the faculty of Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology issued a statement on “The Leadership of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Significance of Canon 28 of Chalcedon.” The statement included the following paragraph:

[C]anon 28 of Chalcedon explicitly granted to the bishop of Constantinople the pastoral care for those territories beyond the geographical boundaries of the other Local (autocephalous) Churches. At the time of the fifth century, these regions commonly were referred to as ‘barbarian nations’ because they were outside the Byzantine commonwealth. (St. Paul in Romans 1:14 also had used the term ‘barbarians’ to refer to those beyond the old Roman Empire.) Canon 28 of Chalcedon appears to clarify the reference in canon 2 of the Council of Constantinople which says that churches in the “barbarian nations” should be governed “according to the tradition established by the fathers.”[3]

So here we have the “barbarian lands” theory fully set forth. As articulated by the Holy Cross faculty, Canon 28’s reference to “the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses among barbarians” was meant by Chalcedon to refer to “those territories beyond the geographical boundaries of the other Local (autocephalous) Churches.”

But that’s not what the canon explicitly says; it’s an interpretation. On its face, the canon seems to refer only to bishops who belong to the dioceses of Pontus, Asia, and Thrace, who are ministering among certain barbarians.[4]

This raises the question, where did the modern “diaspora” interpretation originate? The obvious place to begin looking is in the standard canonical commentators. Zonaras writes of the phrase in question: “They assign to Constantinople also the ordination of bishops in the barbarian nations, which were in the aforementioned dioceses, which are the Alans and Rus, for the former are adjacent to the Pontian diocese, the Rus to the Thracian.” Balsamon explains the boundaries of “Pontus,” “Asia,” and “Thrace,” and then states that “the Alans, Rus, and others are bishops in barbarian lands.” Aristenos tells us, “Only the metropolitans of Pontus, Asia and Thrace will be subject to him, and ordained by him, likewise also the bishops of the barbarians in such dioceses.”

These commentators all hold to a very literal interpretation of the phrase, “the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses among the barbarians.” At the turn of the nineteenth century, we come to St Nikodemos of the Holy Mountain, who, in the Pedalion, repeats Zonaras, saying, “Not only are the Metropolitans of the said dioceses to be ordained by him, but indeed also the bishops located in barbarian regions that border on the said dioceses, as, for instance, those called Alani are adjacent to and flank the diocese of Pontus, while the Russians border on that of Thrace.”[5]

Nowhere in the commentaries, from Zonaras and Balsamon in the twelfth century up to St Nikodemos at the beginning of the nineteenth, is there any hint of the modern “barbarian lands” theory. The late Metropolitan Maximos of Sardis, in his 1976 book on the Ecumenical Patriarchate, writes extensively about the “barbarian” language of Canon 28, but he too does not cite any older source in support of the modern “barbarian lands” theory.[6] So where did this theory originate? As best I can determine, the earliest evidence for the modern theory appeared at the turn of the twentieth century, when a large-scale Hellenic diaspora emerged across the globe, and most notably in the United States.

***

Organized Orthodox Christianity first took root in the contiguous United States in Civil War era, when multiethnic parishes were established in San Francisco (under the Russian Church) and New Orleans (which was loosely connected with the Church of Greece). But it was not until the Ellis Island era of the 1890s that Orthodox parishes began emerging in America at any significant scale. In terms of raw population, the largest Orthodox group in the New World was the Greeks. In the years that followed, these Hellenic immigrants established churches in the eastern United States and, soon, further west. These Greek churches were loosely connected with either the Ecumenical Patriarchate or the Church of Greece, or, occasionally, Alexandria or Jerusalem. In practice, these new Greek churches were functionally independent, run by lay boards of trustees that hired and fired their priests at will. Fr John Erickson writes, “It is little wonder that a few parishes were misled into hiring impostors, usually vagrant monks who pretended to be ordained priests in order to obtain the fees customarily paid for performing baptisms, marriages, and other vital ‘rites and ministrations.’”[7]

For Greek Orthodoxy, America was a wild west. It wasn’t quite so chaotic for some of the other Orthodox ethnic groups in America. The Russian Church had an established archdiocese in America, with a resident archbishop and priests who were appointed to their parishes in an orderly manner. The Antiochians and Serbs had their own ethnic vicariates under the Russian archbishop, but while the Ecumenical Patriarchate never objected to this early Russian jurisdiction in America, neither did it cede the Hellenic diaspora to the authority of the Russian archbishop.

Eventually, the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Church of Greece decided that something had to be done about the Greek communities. In 1907, the Patriarchate established a commission of three Metropolitans to examine the issue of this growing Greek diaspora. Who had authority over these people and their churches? How should the Hellenic diaspora be administered? On November 12, 1907, the Patriarchal Commission presented its report in a meeting of the Holy Synod. A contemporary account summarizes the report and discussion as follows:

The report concludes, basing itself on the holy canons — which are not quoted — that all the Greek Churches and communities abroad, not included in the canonical territory of an autocephalous Orthodox Church, depend on the Ecumenical Patriarchate. For the good success of this project, the Commission was of the opinion that the Ecumenical Patriarchate should write to the autocephalous sister Churches to ask the Ecumenical Patriarchate for formal consent for the appointment of hierarchs and clergy in charge of their annexes abroad. In this case, the Ecumenical Patriarchate would have no right to refuse; it would be, in short, a pure formality.

His All Holiness Patriarch Joachim III disagreed. He proposed that, in Europe at least, things remain as they are, with communities everywhere continuing to depend on their own churches. As for the Greek communities in America, they would report directly to the Holy Synod of Athens.[8]

As best I can tell, this report is the earliest example of the “barbarian lands” theory of Canon 28, although the canon itself is not directly cited. It’s noteworthy that the Patriarchal Commission and Patriarch Joachim himself disagreed about the application of this concept.

The following March, 1908, Patriarch Joachim and his Holy Synod issued a Tomos that ceded the Patriarchate’s rights in the diaspora to the Church of Greece.[9] The Tomos clearly sets forth the “barbarian lands” theory as the basis for the Patriarchate’s jurisdiction in the diaspora, while at the same time focusing specifically on ethnic Greeks, not all Orthodox Christians. The Tomos begins by asserting that the Holy Synod is attempting to find, in the ancient canons, a basis for dealing with a specific pastoral challenge that has arisen. The Synod writes, “What do we do now, through the present Patriarchal and Synodal Tomos, is concerning those outside the established boundaries of the individual autocephalous ecclesiastical regions scattered in Europe and America and in other countries with Greek Orthodox Churches, which until now, are unstable and undefined in respect to a singular order of a canonical spiritual authority.”

The Tomos then lays out the barbarian lands theory:

Because the spiritual dependence of the said churches was thus abnormal and indefinite, the canonical order was clearly violated, for it was abundantly manifest that neither was the Most Holy Church of Greece under our Patriarchal Throne, being sovereign in autocephaly with defined boundaries, nor was another Church or Throne able to presume, by its own authority, to canonically reach beyond the boundaries of its own region, except for our Most Holy, Apostolic, and Patriarchal Ecumenical Throne, both from the prerogative granted to It to ordain the bishops in the barbarian lands and those declared beyond defined ecclesiastical regions, as well as of Itself by the intercessions, properly justified to exercise supreme spiritual protection for said churches on foreign [soil].

The Tomos then states that the Patriarchate cedes to the Church of Greece “the right of oversight of all Greek Orthodox Churches in the diaspora.” The Tomos outlines various conditions – Holy Chrism must come from the Ecumenical Patriarch, who is to be commemorated liturgically; parish priests must receive a canonical appointment from the Holy Synod of Greece; and each parish must make financial contributions to the Patriarchate.

Initially, we have a very expansive canonical claim: the reference to Constantinople’s right “to ordain the bishops in the barbarian lands” is a clear invocation of Canon 28, and the Tomos asserts that only Constantinople can “canonically reach beyond the boundaries of its own region.” According to the Tomos, no other Church may exercise jurisdiction in the diaspora, in regions beyond its defined canonical territory. This would presumably apply to the claims of the Russian Church which had bishops in the America and Japan.

But the Tomos is clearly focused on the Greeks, not Orthodox people in general. It’s not that the Tomos concedes those non-Greeks to other Orthodox Churches; it’s that the Tomos doesn’t mention non-Greek Orthodox people in the diaspora.

***

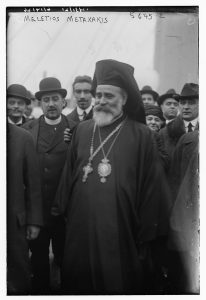

Under the 1908 Tomos, the Church of Greece was to send a bishop to America, but the Greek parishes in the diaspora became even more divided. For ten years, until 1918, this didn’t happen. This, of course, was the era of the “Royalist-Venizelist” split, with Greek parishes in America dividing along political lines according to factions in the Kingdom of Greece. Then, in 1918, the new Metropolitan of Athens (not yet with the title “Archbishop”), Meletios Metaxakis, traveled to the United States with his friend, Bishop Alexander Demoglou, and began organizing the Greek parishes into what would become the Greek Archdiocese. This Archdiocese held its first Clergy-Laity Congress in 1921, and at the same time, the entity was legally incorporated. As an institution, the Archdiocese marked its 100th anniversary last year, in 2021.

Why, then, do we celebrate 2022 as the centennial of the Archdiocese? By 1921, Meletios was persona non grata in Greece; his fortunes rose and fell along with his political ally Venizelos, and when the Royalist faction regained the upper hand, Meletios was out as Metropolitan. He came back to America, but this time, he was an exile. When the Greek Archdiocese was established in the summer of 1921, the ecclesiastical position of both the Archdiocese and Meletios was quite uncertain.

Everything took a dramatic turn at the end of the year: In December, Meletios was suddenly elected Ecumenical Patriarch in an irregular procedure involving a minority of the eligible bishop-electors. The Ecumenical Throne had been vacant since 1918, an uncertain period that coincided with the Greco-Turkish War. In an instant, Meletios went from ousted Metropolitan of Athens to the leading hierarch in the Orthodox world. He was enthroned in February, and one of his first acts as Patriarch, on March 1, was to revoke the 1908 Tomos and reestablish the Patriarchate’s authority in the diaspora.

This revocation was done via a Praxis issued by Meletios and his Holy Synod.[10] This document is the first place I’m aware of where a fully expansive “barbarian lands” theory is set forth, with no limitation to ethnic Greeks. The Praxis describes the 1908 Tomos as having granted to the Church of Greece the Patriarchate’s “canonical right of supreme power and protection over Greek Orthodox Communities in the Diaspora and which were outside the established boundaries of the Most Holy Orthodox Autocephalous Churches.” The Praxis specifies that these communities were “Greek-speaking.” And because the Church of Greece had failed to successfully organize these communities, Constantinople was taking back its power over the diaspora, “by Her inviolable right to manage and conduct by Her own authority the canonical authority belonging to Her from the sacred canons and the Ecclesiastical order, in which is included the ecclesiastical supervision of those outside and in the diaspora of Orthodox Communities.” So the Praxis jumps from a focus on Greek-speaking people to all Orthodox communities, of any ethnicity or language. To remove any doubt as to the expansiveness of this claim, the Praxis reaches its crescendo in its penultimate paragraph:

She reinstates immediately complete and intact Her ruling canonical rights, and immediate supervision and governance – without exception – of all Orthodox Communities found outside the boundaries of each of the Autocephalous Churches, whether in Europe, or America, or anywhere else; bringing them immediately under the immediate Ecclesiastical dependence and guidance, and determines those that arise thereafter will belong only to Her and from Her possess the validity of their Ecclesiastical formation and actuality.

Then, on May 17, Meletios and his Holy Synod issued a Tomos establishing the Archdiocese of North and South America as an eparchy of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.[11] This May Tomos begins by reiterating the “barbarian lands” theory: “The canonical ordinances and the centuries-old practice of the Church ascribe the Orthodox communities which are found to be outside the canonical boundaries of the individual Holy Churches of God under the pastoral governance of the Most Holy, Apostolic, Patriarchal, Ecumenical Throne.”

Unlike the 1908 Tomos, which begins with an expansive claim of territorial jurisdiction, but then shifts to focus only on the Hellenic diaspora, and unlike the earlier March 1922 Praxis that revoked the 1908 Tomos, the 1922 Tomos makes no reference at all to ethnicity. The Tomos decrees that “from now on all Orthodox communities found in North and South America, and whatever Orthodox ecclesiastical bodies which exist now, or henceforth shall be founded, are to be known as members of one body, namely, the ‘Orthodox Archdiocese of North and South America.’” Not “Greek Archdiocese,” but “Orthodox Archdiocese.”

The Tomos ranks this Archdiocese fifteenth in the ordering of the Metropolises of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and establishes the structure of the Archdiocese. The Archdiocese is to be divided into dioceses and the Tomos recommends four to begin with. Curiously, New York is not mentioned at all. The Archbishop has Washington, DC and Philadelphia, and then the other three dioceses are Chicago, Boston, and California. The Archbishop and the diocesan bishops comprise an Eparchial Synod.

The Tomos gives the Archdiocese quite a bit of independence – certainly much more independence than the current Greek Archdiocese has. In the case of a vacancy, either in the position of Archbishop or one of the diocesan sees, the Eparchial Synod elects the replacement, with this procedure: The Holy Synod of Constantinople has a list of eligible candidates for bishop, and then a standing council of clergy and laity (basically the equivalent of the current Archdiocesan Council, or a Metropolis Council) “puts forward” its favored candidates – basically nominations. The Eparchial Synod elects from the list of nominees, subject to approval by the Ecumenical Patriarch.

Of course, none of this applies today – ever since the restructuring of the Archdiocese in 1930-31, the Holy Synod of Constantinople has controlled the selection of new Archbishops, with no role for the Archdiocese itself in the selection process, except for an advisory one (supernumerary in character) assigned to the Archdiocesan Council.

As we’ve seen, the 1922 Tomos does not have an ethnic character – it seems to envision the Archdiocese as being the sole canonical body for all Orthodox Christians in North and South America., the Archdiocese have never had the pan-Orthodox character that seemed to be implied by the Tomos. The original Charter of the Archdiocese, also issued in 1922, refers to it as the Greek Archdiocese, and it is designed for those Orthodox Christians who use Greek as their liturgical language. The Charter specifies that the Archdiocese exists to organize the spiritual life of Greeks and of Orthodox Americans of Greek origin.

***

These two acts by Meletios and his Synod were just a part of a flurry of activity by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In March, the same month the 1908 Tomos was rescinded, Meletios spent a week negotiating with a Serbian Orthodox delegation about the autocephaly of the Serbian Church. Another tomos created the Metropolis of Thyateira and Great Britain to oversee parishes in Central and Western Europe. The Tomos on North and South America came in May; in September, Meletios issued a letter on the validity of Anglican orders. It was not a coincidence that Britain was one of the decisive players in the as-yet-uncertain future of Turkey, and Meletios had, for several years, publicly expressed hope that the Hagia Sophia might be returned to the Orthodox.

Meletios’s election and all this activity I just described took place during a period of stalemate in the Greco-Turkish War, a tension-filled lull before the Asia Minor Catastrophe. In February and March, when Meletios was enthroned and when he rescinded the 1908 Tomos, the Allies, led by Britain, held diplomatic meetings in London, trying to broker an armistice. Ataturk wasn’t having it, and the Greeks were increasingly demoralized and divided. In April, Meletios wrote to Venizelos, “It is certain that all of us here and in Smyrna and in Athens are struggling in the dark and hitting out at friends and enemies without any definite aim any more…”[12] In the weeks leading up to the Tomos on the diaspora, the Soviet government – which, for its part, was busy persecuting the Russian Orthodox Church – sent large sums of money to aid Turkey. The Greeks began to fixate on Constantinople. Everyone was going for broke.

This is the context in which Meletios and his Synod rescinded the 1908 Tomos and established the Archdiocese of North and South America. The future of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, of Orthodoxy in not only Turkey but in Russia and, frankly, everywhere else, was suddenly in doubt. The great empires that had defined the Orthodox world for centuries – Russian, Ottoman, Habsburg – were suddenly gone, and in their place was uncertainty at best, and in many cases persecution and destruction. In this context, Meletios, perhaps the most creative, ambitious, and politically-minded Patriarch in history, dramatically reinvented the very institution of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, recasting its purpose as the master of an expansive “barbarian lands” that covered the majority of the globe.

***

At the beginning of this paper, I quoted the future Patriarch Christophoros of Alexandria, who claimed that the Ecumenical Patriarchate began to extend its jurisdiction over the diaspora only in 1922 – that is, with this 1922 Tomos. Although we can trace the Patriarchate’s claim to the diaspora back a little further, to 1908, Christophoros appears to be generally correct: the “barbarian lands” theory does appear to date to the early 20th century: first clearly elucidated in the 1908 Tomos and not asserted with any practical effect until 1922.

One final postscript. Patriarch Meletios is the father of the modern “barbarian lands” theory, but within a few years, he repudiated that theory. He was forced out of Constantinople by the Turks in 1924, and in 1926 he was elected Patriarch of Alexandria. The next year, he deposed a priest who was in Morocco, which in ancient times had been under Rome. The priest appealed to the Ecumenical Patriarch, who claimed jurisdiction over Morocco (which at this point would be considered “diaspora”). Meletios responded by claiming all of Africa for Alexandria, although up to this point his title only covered “Alexandria, Libya, Pentapolis, Ethiopia, and All Egypt.”[13] It’s here, in 1927, in defiance of the “barbarian lands” theory, that Alexandria’s claim to “All Africa” begins. The Ecumenical Patriarchate didn’t accept this “All Africa” claim until 2001.

I am certainly open to being proven wrong about this. I’m not a canonist or a Byzantine historian; perhaps Balsamon and Zonaras simply ignored the “barbarian lands” theory when they expounded upon Canon 28. It’s possible, I suppose, that St Nikodemos at the turn of the nineteenth century also overlooked the theory, and perhaps the Ecumenical Patriarchate did object to Russian jurisdiction in America in some as-yet-undiscovered document. But the simplest explanation – the explanation that is supported by the evidence we do have – is that the “barbarian lands” theory of Canon 28 has its origins at the turn of the twentieth century, when a sizeable Greek diaspora emerged around the world, and then, soon thereafter, the Ecumenical Patriarchate under Meletios Metaxakis had to reinvent itself in the face of a once-in-500-years threat to its very existence.

Endnotes

[1] Christophoros, Metropolitan of Leontopolis, “The Position of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the Orthodox Church (1924)”, Orthodox History (August 26, 2020), https://www.orthodoxhistory.org/2020/08/26/the-position-of-the-ecumenical-patriarchate-in-the-orthodox-church-1924/, translated by Sam Noble from the French, published as “Le patriarcat œcuménique vu d’Egypte,” Revue des études Byzantines 137 (1925), 40-55.

[2] Rhalles and Potles, 2:280-286, quoted in Fr Patrick Viscuso, Orthodox Canon Law: A Casebook for Study, 2nd ed. (Holy Cross Orthodox Press, 2011), 83. Here is an alternative translation: “”The metropolitans of the dioceses of Pontus and Asia and Thrace, and also the bishops in the [areas] of barbaricum of the aforementioned dioceses, should be ordained only by the aforementioned most blessed see of Constantinople.” Ralph W. Mathisen, “Barbarian Bishops and the Churches ‘In Barbaricis Gentibus’ During Late Antiquity, Speculum 72:3 (July 1997), 669. And again, Fr John Erickson: “Consequently [kai hōste], the metropolitans – and they alone – of the dioceses of Pontus, Asia and Thrace, as well as the bishops of the aforementioned dioceses who are among the barbarians [eti de kai tous en tois barbarikois episkopous tōn proeirēmenōn Dioikēseōn], are to be ordained by the aforementioned most holy throne of the most holy Church of Constantinople.” Fr John H. Erickson, “Chalcedon Canon 28: Its Continuing Significance For Discussion of Primacy in the Church,” 1.

[3] Faculty of Holy Cross Greek Orthodox School of Theology, “The Leadership of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Significance of Canon 28 of Chalcedon,” Greek Orthodox Archdiocese of America (April 30, 2009), https://www.goarch.org/-/the-leadership-of-the-ecumenical-patriarchate-and-the-significance-of-canon-28-of-chalcedon.

[4] Mathisen explains, “The pronouncement of 451 would have put Constantinople on the same administrative level as Antioch and Alexandria, which already claimed oversight over the barbarian churches in areas adjoining the dioceses of Oriens and Aegyptus respectively. It also would have closed a loophole that could have left Caesarea as metropolitan see of Armenia, outside the effective control of Constantinople, even when Constantinople had authority over Caesarea itself. Any barbarian bishops in territories adjoining the dioceses of Pontus, Asia, and Thrace now were to be responsible directly to Constantinople; other ties were abrogated.” Mathisen, 669. Archimandrite Cyril Hovorun writes, “The Patriarchs of Constantinople were not given a privilege to consecrate bishops among the ‘barbarians’ who lived out of the Empire, in Barbaricum. This is clear from the fact that there were no bishops there, except may be in Crimea. Only the bishops for the ‘barbarians’ who dwelled within the three dioceses of the Empire were consecrated by the Patriarchs of Constantinople.” Cyril Hovorun, “On the Formation of Jurisdictional Limits of Eastern Churches in 4-5th Centuries,” Orientale Lumen IX Conference Proceedings. Society of St John Chrysostom Eastern Christian Publications. 2005. 87-103. Erickson concurs: “What is the meaning and application of the phrase ‘bishops of the aforementioned dioceses who are among the barbarians’? It is quite clear, first of all, that this does not mean unlimited authority over bishops among the barbarians wherever they may be – over all the ‘diaspora’ we might say today. It did not mean authority over regions of the upper Nile, which not only were adjacent to Egypt but also were evangelized from there, or authority over regions to the east of the civil diocese of Orient, where similar considerations apply. In all those regions, supervision in matters relating to ordination and church order had long been in the hands of Alexandria and Antioch respectively from ante-Nicene antiquity, and so they remained. In addition, given the obvious concern for consistency with earlier canons evident elsewhere in this psiphos of Chalcedon, it is highly unlikely that the council tried to modify the provisions of canon 2 of I Constantinople (the second ecumenical council), which had stated that ‘the churches of God among the barbarian peoples [en tois barbarikois ethnesi] are to be governed according to the custom which has prevailed from the time of the Fathers.’” Erickson, 12.

[5] St Nicodemus the Hagiorite, The Rudder (Pedalion) of the Metaphorical Ship of the One Holy Catholic and Apostolic Church of the Orthodox Christians, or All the Sacred and Divine Canons (Orthodox Christian Educational Society, 1957), 276.

[6] Maximos, Metropolitan of Sardes, The Oecumenical Patriarchate in the Orthodox Church: A Study in the History and Canons of the Church (Thessaloniki: Patriarchal Institute for Patristic Studies, 1976), 221-229.

[7] Fr John H. Erickson, “Organization, Community, Church: Reflections on Orthodox Parish Polity in America,” Greek Orthodox Theological Review 48:1-4 (2003), 72. See also Matthew Namee, “The Myth of Unity,” Orthodox History (January 29, 2018), https://www.orthodoxhistory.org/2018/01/29/myth-of-unity/.

[8] G. Bartas, “Chez les Grecs Orthodoxes,” Échos d’Orient 68 (1908), 54-55. Published in English as “Who Had Jurisdiction Over the Diaspora in 1907?” Orthodox History (August 12, 2022), https://www.orthodoxhistory.org/2022/08/12/who-had-jurisdiction-over-the-diaspora-in-1907/.

[9] Original Greek text published in Paul Manolis, The History of the Greek Church of America in Acts and Documents, Vol. 1 (Ambelos Press, 2003), 310-315. Click here to view the Greek original and click here to view an English translation.

[10] Published in Εκκλησιαστική Αλήθεια 1922, 129-130. Click here to view the Greek original and click here to view an English translation.

[11] Published in Εκκλησιαστική Αλήθεια 1922, 218-220. Click here to view the Greek original and click here to view an English translation.

[12] Michael Llewellyn Smith, Ionian Vision: Greeks in Asia Minor, 1919-1922 (University of Michigan Press, 1973), 274.

[13] J. Lacombe, “Chronique des Églises Orientales,” Revue des études Byzantines 174 (1934), 230.

Leave a Reply