Recently, on Twitter, a user named @EphraimChrist14 tweeted at our Orthodox History account, “Why are bishops not selected from those living under obedience in a monastery who have gained spiritual experience and are filled with the Holy Spirit? Is that because the bishops and patriarchs are Barlaamites and consider only admin skills and education as relevant?”

This comment — which obviously has an edge to it — raised an interesting question for me: do holy bishops, in fact, live as humble monks for an extended period of time prior to their consecration? In many quarters, this concept is held up as an ideal, but is it actually the case?

The short answer is, no, not really. I gathered information on 24 bishops from the past 200 years who have been glorified as saints, plus a couple who are widely venerated (Patriarch Pavle of Serbia and Metropolitan Leonty Turkevich). The earliest bishop on the list is St Peter of Cetinje, the Metropolitan of Montenegro, who was consecrated in 1781 and died in 1830. The most recent is Patriarch Pavle, who was consecrated in 1957 and died in 2009. Thirteen of the bishops on the list were consecrated in the 19th century, and thirteen in the 20th.

The bishop-saint with the most extensive monastic formation is undoubtedly St Gregory the Teacher of Romania, who lived from 1765 to 1834. St Gregory became a monk at age twenty-five under the great St Paisius Velichkovsky, and he later spent time on Mount Athos and in other Romanian monasteries. At the age of 58, the Prince of Wallachia summoned St Gregory — who at this point was only a hierodeacon — to become Metropolitan of Wallachia, based on his reputation for wisdom and spiritual maturity. This is the kind of path that I think a lot of people have in mind when they imagine monastic formation for future bishops, but it is very much the exception rather than the rule.

St Gregory’s younger Romanian contemporary, St Calinic of Cernica (1787-1868), had a similarly lengthy period of monastic formation. Their fellow Romanian St Joseph the Merciful of Moldavia (1820-1902) lived in a monastery from the age of ten. These three Romanian bishop-saints stand out among 19th-20th century holy hierarchs. Almost everyone else did not have such a monastic formation.

A more typical story is that of St Philaret of Moscow — he went to seminary and then to the Moscow Theological Academy, and after graduation he became a professor. Just before his 26th birthday, he was tonsured a monk and ordained a hierodeacon; a few months later, he was appointed as a seminary dean of students and then ordained a hieromonk. Soon, he was appointed abbot of a monastery; at the same time, he pursued doctoral studies. At no point was he a monk in a monastery under obedience to an abbot; he was, rather, a professor and administrator in higher theological education before climbing the ladder of church leadership further. He went on to become the most prominent and respected bishop in the Russian Orthodox Church in the 19th century. Despite his lack of typical monastic formation, he was a great lover of monasticism, particularly notable for his support of the great Optina Monastery and of Holy Trinity-St Sergius Lavra. This is a theme that seems apparent among these bishop-saints: although most of them didn’t have a “normal” monastic formation themselves, they tended to be patrons of monasticism as bishops.

Saints Benjamin of Petrograd, John Pommers of Riga, Tikhon of Moscow, and Nikolaj Velimirovic all had comparable stories to St Philaret: never really living in a monastery, but living as monks while working in higher theological education. St John Maximovitch was tonsured while studying theology at a university and worked as a teacher, but didn’t live in a monastery. St Raphael Hawaweeny was tonsured and then immediately went to the Halki Seminary to pursue theological studies; St Chrysostomos of Smyrna followed a similar path. St Nicholas of Japan was tonsured a monk and immediately ordained to the priesthood while studying at the St Petersburg Theological Academy, and almost immediately, he set off for Japan.

St Andrei Saguna, another great Romanian hierarch, had kind of a “backwards” track: he pursued theological studies and then worked as secretary to his metropolitan, but later, after becoming a hieromonk, he did live for a few years in a monastery.

St Nektarios of Aegina might be the most beloved bishop-saint in modern times; he did live in a monastery for several years, three as a novice and three more as a simple monk before becoming a hierodeacon and pursuing his education. Two other spiritual giants of modern times, St Ignatius Brianchianinov and St Theophan the Recluse, somewhat surprisingly did not have a classic monastic formation. St Ignatius tried out numerous monasteries as a novice, but he was disappointed at failing to find a suitable spiritual father, and in his later writings, he decried the lack of holy elders in his day (kind of an odd complaint considering he lived during the golden age of the Optina Elders, among others). St Ignatius was made an abbot at the age of 25 despite not having been formed as a simple monk. Then there’s St Theophan, who worked in theological education and then joined the Russian Ecclesiastical Mission in Jerusalem, becoming a church diplomat and then later a bishop. Soon enough, he retired and began the life of seclusion that earned him his moniker.

Several great bishop-saints of modern times were widowers: Innocent of Alaska, Vladimir of Kiev, Kirion of Georgia, Seraphim Chichagov, Luke of Simferopol. (Metropolitan Leonty Turkevich could be added to this list.) Understandably, these men typically did not have any monastic formation, although Vladimir of Kiev is notable for having spent about two years in a monastery between his wife’s repose and his consecration to the episcopacy.

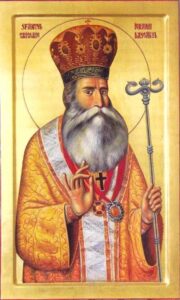

As far as I can tell, no bishop-saint who was consecrated in the 20th century lived as a simple monk, but we might have one soon: Patriarch Pavle, the beloved primate of the Serbian Church, was in a monastery for almost a decade. Also, St Varnava Nastic, who was born in Gary, Indiana and became a confessor for the faith in Serbia, was tonsured in 1940 and then ordained a deacon; he was part of a monastic brotherhood but had an atypical experience that was disrupted by World War II.

All told, of the 26 holy bishops on the list, 18 (69%) did not have a notable period of monastic formation. Another three (Ignatius Brianchianinov, Vladimir of Kiev, and Varnava Nastic) had some small bit of monastic formation, but not what I think people typically envision. So, that’s 21 out of 26 (81%) that didn’t follow the idealized model, leaving just five — Gregory the Teacher, Calinic of Cernia, Joseph of Moldavia, Nektarios of Aegina, and Patriarch Pavle — who were formed in a monastery prior to rising up the ranks of church leadership. In fact, more of these holy bishops were widowers (6) than were simple monks (5).

***

I have to say, I was pretty shocked at these findings. I think many people would have expected the opposite, that perhaps 8/10 bishop-saints came from monasteries and 2/10 did not, rather than the other way around.

That isn’t to say that these holy bishops lacked any sort of spiritual formation — far from it. Six of them were married men, and a great number of them went through seminary and theological academy programs that were highly disciplined. All of these men were noted for their humility and asceticism and self-denial, living truly monastic lives while actively administering their dioceses. They are the best bishops in modern times, after all. But, on the whole, they didn’t come from the monasteries. A great monk will, after many years of struggle, emerge as an abbot or a geronda/starets, but with very rare exceptions, these spiritual giants have not been chosen as bishops. St Seraphim of Sarov, the Optina Elders, the holy Greek elders of recent years (Paisios, Porphyrios, Iakovos, et al), Elder Cleopa Ilie, St Gabriel of Georgia… these are the monastic giants, the men with vast experience in monasteries. They don’t go on to become bishops.

What are the implications of this? It’s kind of hard to say. It’s a dangerous thing to have a clear-cut “bishop track” — celibate clergyman / nominal monk who works in administration or academia but is never a simple monk in a monastery. This can be a source of temptation, a path for an ambitious person to pursue the episcopal office. Yes, a lot of these modern bishop-saints followed roughly that path, but how many others did the same and weren’t so holy? Careerism and ambition are unfathomably dangerous; perhaps the saintly bishops are the exceptions, the ones who somehow took that deadly path and, by God’s grace, thrived? On the other hand, could there be a wisdom in leaving good monks in monasteries and instead selecting bishops from among those celibate clergy who have shown both spiritual maturity and an aptitude for administration? I don’t know the answers, but the data from these modern saints compels these questions.

Leave a Reply