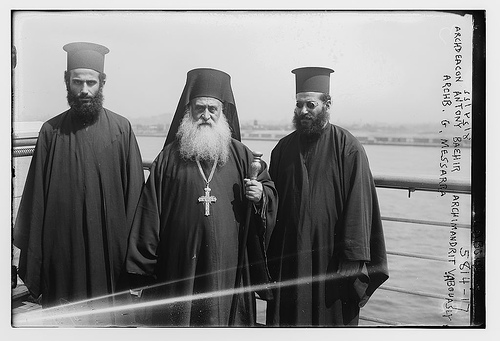

Archdeacon Antony Bashir, Metropolitan Gerasimos Messara, and Archimandrite Victor Abo-Assaley upon their arrival in America in 1922

Antony Bashir arrived in America in 1922, as a 24-year-old archdeacon. He and Archimandrite Victor Abo-Assaly were accompanying the Antiochian Metropolitan Gerasimos Messara, who was ostensibly coming to the US to attend a convention of the Episcopal Church in Portland, Oregon. Soon, however, another agenda emerged: the establishment of an Antiochian Archdiocese in America. At that point, there were two factions of Arab Orthodox in America — the Russy, who were loyal to the Russian-backed Abp Aftimios Ofiesh; and the Antacky, who followed the rogue Antiochian Metropolitan Germanos Shehadi. Although he was from the Patriarchate of Antioch, Met Germanos was not supported that Church.

Into this chaos came Met Gerasimos Messara and his two lieutenants. By 1924, Fr. Victor Abo-Assaley was consecrated as the first official Antiochian bishop for America. Bashir had been ordained shortly after his arrival in the US, in 1922. He spent two years in Mexico, where his mother and brother were living. He ultimately ended up back in America, serving as a parish priest in Indiana.

In 1933-34, a remarkable thing happened: all of the many Arab Orthodox episcopal claimants suddenly vanished. Well, not exactly vanished, but, as a friend once put it, “God wiped the slate clean.” The first to go was Bp Emmanuel Abo-Hatab, the leader of the Russy faction, who died in May of 1933 (ironically, Met Germanos Shehadi officiated at his funeral). Abp Aftimios Ofiesh, who had previously led the Russy group and then sort of drifted off into his own little world, effectively ended his episcopate by marrying a young girl a couple of months after Abo-Hatab’s death. The same year, Met Germanos Shehadi finally left the country, returning to Syria, where he soon died. Abp Victor Abo-Assaley hung on the longest, dying in September 1934. And just to make things complete, Bp Sophronios Beshara, who said that he had inherited Ofiesh’s (already dubious) claims, also died in ’34.

So suddenly, what had been an incredibly complex ecclesiastical quagmire morphed into a claim-free simplicity. In 1935, the now-leaderless (and thus at least nominally “united”) Antiochians held elections for a new hierarch. The top two vote-getters were the still-young (37-year-old) Archimandrite Antony Bashir, and a Toledo archimandrite named Samuel David. Bashir got the most votes, but a strong minority favored Samuel David. Both men were consecrated as bishops on the very same day in 1936, Bashir in New York, David in Toledo. The story is so complicated that I won’t even try to explain it. Bottom line, the American Antiochians were still hopelessly divided, with the result being the establishment of two overlapping Antiochian Archdioceses, one based out of New York, the other Toledo. This “Toledo-New York schism” would last until the 1970s.

***

As for Bashir, he was a fascinating man. Intellectually brilliant, he was an accomplished translator and scholar. He was a strong proponent of Orthodox unity in America, and was one of the driving forces behind the formation of the short-lived Federated Orthodox Greek Catholic Primary Jurisdictions in America. The Federation was essentially a proto-SCOBA body, and one of its biggest achievements was the legal incorporation of several Orthodox jurisdictions in the State of New York — including the Antiochian Archdiocese. When the Federation collapsed in 1944, Bashir kept it alive on life support. Into the 1950s, he was still listed as the head of the Federation, even though it did not, as a practical matter, exist at all. When SCOBA was formed in the early 1960s, Bashir was again a central player.

He also advocated the use of English in church services. Early in his tenure as metropolitan, on February 4, 1939, he was interviewed on this topic by the Brooklyn Daily Eagle:

The Eastern Orthodox Church has many national branches, each conducting its services, as a rule, in the native language of the country. The Syrian Orthodox is narrow in its dogma and doctrine, clinging to the Apostolic Nicene creed and the seven ecumenical councils of the church. We cannot change that. We acknowledge Christ as our only head.

But we are living in America and in the twentieth century and must make our Church conform so far as we can to the American way of living and meet the demands of the rising American generation, which clings to the old religion but is no longer interested in retaining the old Arabic of their fathers. For the old people and our older priests we still use the Arabic, but a Church that would cling to the old exclusively would die with the generation that demanded it.

We are new to America and there are no rules of jurisdiction to apply to us. Our Church laws antedate America, but our Syrians become Americanized more quickly than almost any other race. We are gradually transforming the ritual into English, keeping, of course, the ceremonial traditions of the Church. Our Sunday Schools are wholly in English. Our series of music with English words, the first one almost ready for publication, will present our ancient Byzantine music in a form the new generations can understand and appreciate.

Some of the older priests do not understand English, but most of them accept the new orders without question. I am drawing young Americans into our priesthood. I have ordained eight young Americans as priests within the last two years.

We have to cater to the old, who grow fewer each year, but it is to the younger generation that the Church looks for its continuance. Our young people call themselves Americans, not Syrians. I believe that in the future all branches of the Eastern Orthodox Church, especially in this country, will unite into one great American Orthodox Church, with English as the universal language.

Bashir said all this in 1939 — eighty-five years ago. But actually, he wasn’t the first bishop, or even the first Syrian/Antiochian bishop, to push for a widespread use of English. That distinction belongs to St. Raphael Hawaweeny, who, by the time of his death in 1915, had over half of his parishes (13/25) using exclusively English, and 84% (21/25) using at least some English. I get the impression that the Antiochians backtracked in this regard after St. Raphael’s death — certainly, they must have, if Bashir needed to re-initiate a push for English in the late 1930s.

Under Bashir, the convert priest Fr. Michael Gelsinger gained a great deal of influence, and numerous converts joined the Antiochian Archdiocese, which far outpaced the other Orthodox jurisdictions in its openness to American converts. Bashir founded the modern-day Word Magazine (the original Al-Kalimat having ceased publication long before; in reality, the two publications are totally distinct aside from their names). He started the Archdiocesan youth group (SOYO), as well as the Western Rite Vicariate. Many of the most distinct features of the Antiochian Archdiocese today can be traced to Bashir, and it was upon his foundation that his successor, Metropolitan Philip Saliba, built.

Bashir died in Boston on February 16, 1966, a month shy of his 68th birthday.

Through the prayers of our Holy fathers and mothers, Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy on us and save us! 🇺🇸☦️🕰