Earlier this year, I conducted a series of interviews with Fr Alex Karloutsos, and last week, I published my first article based on those interviews, chronicling his rise from relative obscurity to the highest echelons of power in America. Today, I will continue this series based on Fr Karloutsos’s memories, focusing on the early years of his relationship with the eventual Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew and his role in Bartholomew’s own rise to power.

***

“Growing up under Archbishop Iakovos, nobody really knew or cared about the Ecumenical Patriarch,” Fr Alex Karloutsos told me. “The center of our universe was America. They would talk about the patriarchate, but it was like a grandmother. You know, we love our yiayia, but it was old fashioned; no vision was coming from there.”

Following the death of Patriarch Athenagoras in 1972, the Turkish government blocked a swath of top candidates in the patriarchal election, resulting in the surprise election of the obscure, kindly, but untested Patriarch Dimitrios. Behind the scenes, one of the vetoed candidates, the powerful Metropolitan Meliton of Chalcedon, did what he could to run things in Istanbul. But the power of the Phanar was at a low point.

Over in America, thanks to Fr Karloutsos, Archbishop Iakovos and the Greek Archdiocese were on the rise, with newfound access to the centers of political power in Washington. Karloutsos had built relationships with both political parties as well as Greek philanthropists, and it was Iakovos, not anyone in Istanbul, who laid claim to the most prominence in the Greek Orthodox world.

It was right at this point – around the time that Fr Karloutsos met Ronald Reagan – that Meliton of Chalcedon made a personal visit to the United States.

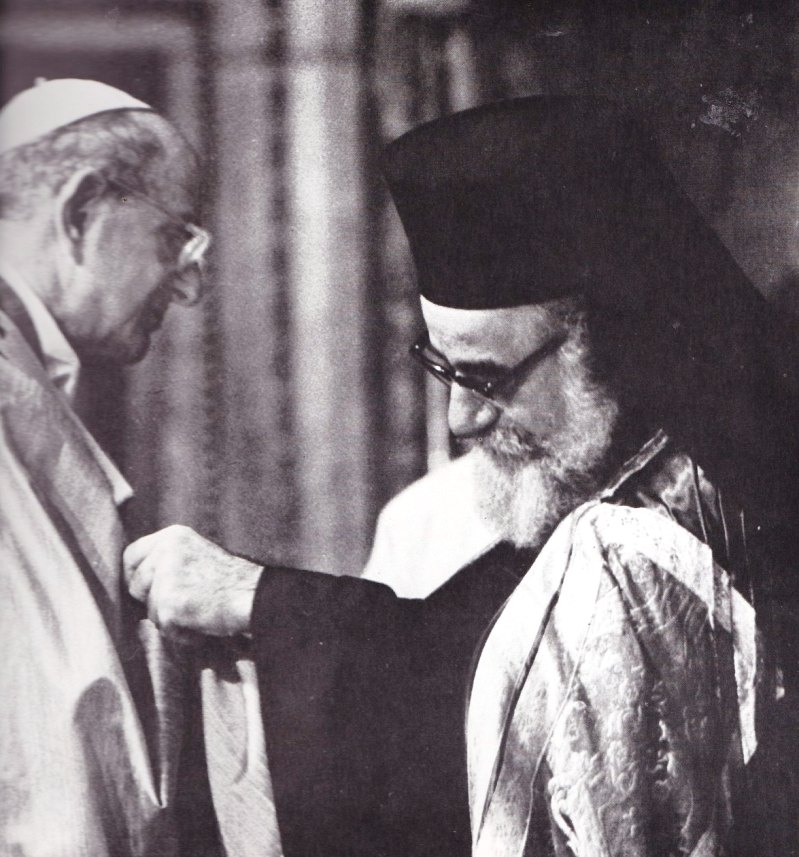

Metropolitan Meliton and Archbishop Iakovos were old seminary classmates and rivals. A few years earlier, when Pope John Paul I died, Archbishop Iakovos was asked by President Jimmy Carter to be a member of the U.S. Presidential delegation at the pope’s funeral. He asked the patriarchate for permission to attend, but his request was denied. Meanwhile, Metropolitan Meliton was present, representing the Ecumenical Patriarch. Some newspapers even reported that Meliton was the “head of the Greek Orthodox Church.” Iakovos was furious and threatened to resign as archbishop, although he didn’t follow through on it.

On his visit to America, Metropolitan Meliton – who was a very shrewd man – immediately took notice of Fr Karloutsos, who was obviously (at least to Meliton) Iakovos’s secret weapon.

Meliton had two up-and-coming disciples: the young hierarchs Bartholomew and Joachim, who were best friends. Bartholomew was a rising star, installed at Meliton’s recommendation as the first head of the private office of the Ecumenical Patriarch. By the early 1980s, he was metropolitan of the ancient see of Philadelphia (in Asia Minor). And Bartholomew was from the island of Imbros, which was also the home of Iakovos – in fact, Iakovos’s sister, Chrysanthe, was Bartholomew’s godmother. Undoubtedly, upon returning to Turkey, Meliton told Bartholomew and Joachim about Fr Karloutsos.

The following year, 1983, Metropolitan Bartholomew came to North America to attend the World Council of Churches meeting in Vancouver, British Columbia. While he was on this side of the Atlantic, he made a point of meeting Fr Karloutsos. “When I met Bartholomew in 1983, he was forty-three years old, and I was thirty-eight,” Karloutsos said. “Both of us felt a big commitment to the Church: him to the Mother Church of Constantinople and me to the Archdiocese of America.”

Shortly after this, Metropolitan Meliton had a stroke, and, at Archbishop Iakovos’s invitation, Bartholomew brought his spiritual father back to the United States for therapy in White Plains, New York. Every day, for forty days – at the direction of Archbishop Iakovos – Fr Karloutsos drove Bartholomew to the rehab center to care for Meliton during his therapy. “That’s when Bartholomew and I became very, very close,” Karloutsos said. “We were together every day. We could talk about different things, our vision, the church. I introduced him to lay people. He started seeing America differently.”

Bonding

In April 1985, Fr Karloutsos and his wife Xanthi were invited by Tim Maniatis and Cleo Zampetis, who at the time were the leaders of AHEPA (a Greek-American organization), to visit Turkey. Up to that point, says Karloutsos, “I had never been to the Ecumenical Patriarchate. I had to get permission from Iakovos, and he gave me permission, and he asked me to bring back relics from the Armenian Catholicos. I think later, he probably cursed the day he approved it.”

Fr Karloutsos had a general understanding that the condition of the Greek Orthodox in Turkey was bad, but he didn’t understand the magnitude of the situation until he paid his first visit to the Phanar. “I remember going up to the patriarchate. The roads had hundreds of potholes in them right in front of the patriarchate. It looked like crap. And we see a gate closed. And they describe, ‘Well, this is where they hung Gregory the Fifth.’ I said, ‘What?’ ‘This is where they hung Gregory the Fifth, 1821, April 10.’ I never knew it. And I looked up and there was a burnt down building. And I said, ‘Why is this building burnt down?’ They said, ‘We don’t have any influence. The Turks won’t let us rebuild it. Burnt down in 1941.’ I said, ‘Wait a minute – 1941? It’s 1985 and you guys can’t get this thing done?’”

Then he went into the makeshift headquarters of the patriarchate, where he met Patriarch Dimitrios (“he was a saintly figure”). Bartholomew was there, too. “And I just started crying like a baby. We were all crying because we had heard about the Holy Mother Church, but we never really were touched by it before.” Patriarch Dimitrios asked Metropolitan Bartholomew to take the group on a tour of the patriarchal compound, and later, Bartholomew broke protocol to have Fr Karloutsos celebrate the Divine Liturgy as the first, despite lacking seniority. Their friendship was growing.

The AHEPA delegation was ready to leave for the next stop on their trip, but Bartholomew had other plans. He pulled Fr Karloutsos aside. “I don’t want you to go on the trip immediately. I have a surprise for you and your presbytera. I can’t tell you what it is, but make sure you have your passports.” Karloutsos, a bit confused, agreed and got together his luggage. They drove to the airport.

“I said, ‘Where are we going?’” Fr Karloutsos recalls. “He says, ‘We’re going to Smyrna. Didn’t you tell me your family is from Smyrna?’ So we get on the plane and we’re talking, we’re getting to know each other. He spent more time talking with my wife than with me. We got to the hotel, we’re eating, and then in the evening we sat on a balcony overlooking the port. It’s beautiful. I mean, you wouldn’t believe it, it was so beautiful. And Bartholomew said to me, ‘Look at the waters? Isn’t it beautiful to see how beautiful the blue waters are, the green waters? Did you ever see anything like that?’ I said, ‘Oh my God, no. It’s really peaceful here.’ Then he goes, ‘Well, do you know what the colors were in 1922?’ I go, ‘What do you mean?’ He says, ‘The Asia Minor Catastrophe! Your family! Your legacy! People butchered here!’ And he brought me back. That’s what Bartholomew could do. And I had tears in my eyes as he was describing the slaughter of the innocents, the genocide, and I said, ‘How do we honor their memory?’

“Then we got in a bus and drove to Ephesus. We visited the house of Mary, which was an imagined shrine that the Turks put up there, and that angered me. They’re restricting us, restricting the practice of our faith! And whenever they can, they make money off of our faith! So we went to Saint John’s tomb, and we walk up to this simple grave. It was a beautiful grave, but it was simple. And Bartholomew says, ‘This is Saint John’s grave.’ I said, ‘Saint John the Theologian? St John the Theologian was here!’ I said, ‘My God, Saint John, the Apostle of Love!’ I started getting emotional. Again, I cried. We were with a crowd of tourists, and we all walked away, and I thought Bartholomew was with us. Then all of a sudden, there was an energy field that made everybody turn around to look at what was calling us back. And there you saw Bartholomew on his knees crying and praying at the tomb of Saint John.

“That hit me right here. We went back to the Phanar and I said, ‘This is ridiculous. We have to do something. How can you allow this building to be burned and not rebuilt?’ Bartholomew said, ‘We can’t get permission. We’ve tried to, we’ve tried everything, but no one is helping us. It’s like the paralytic before the pool of Bethesda.’ So I said to him, ‘I have an idea. Jimmy Carter is going to Greece in July. Maybe I can convince him to come to Constantinople, to raise his voice and support the rebuilding of the patriarchate.’ And Bartholomew said, ‘If you could do that, Alex, we would be very grateful.’”

Jimmy Carter’s Trip to Istanbul

Fr Karloutsos returned to America a changed man. It was as if scales had fallen from his eyes; the motherless son found in the Ecumenical Patriarchate a mother that he wanted to serve and defend. But he was still a servant of Archbishop Iakovos.

“He asked me about my trip. I thought it was a matter of interest, but it was more for gathering intelligence.” But Fr Karloutsos demonstrated a vital discretion: “I didn’t tell him that I offered to bring Jimmy Carter to Constantinople.”

Jimmy Carter had been out of office for a few years by then, and he was fundraising for the Carter Center at Emory University. Fr Karloutsos had arranged for the Greek Archdiocese to host a fundraiser for the Carter Center, and through that, he’d developed relationships with two of Carter’s top advisors – Carter’s childhood friend Arthur Cheokas and his chief development officer George Schira. Karloutsos called Schira and proposed that the ex-president’s planned trip to Greece and Cyprus should include a stop in Istanbul to visit the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

Carter himself was open to the idea but wanted to know what Iakovos thought. Fr Karloutsos had to handle the archbishop delicately. He arranged for a meeting between the archbishop and Cheokas, Schira, and Bishop Silas of New Jersey, who were going to accompany Carter on his trip. They propose the idea of Carter visiting the patriarchate, but the archbishop was completely opposed, says Karloutsos, responding, “I’m against the trip. It’s not the right time, So please tell President Carter that I’m against it. I appreciate his sentiments, but he should not go and please tell him that I’m against the trip unequivocally.”

The group came out of their meeting with Iakovos and broke the news to Fr Karloutsos. They were frustrated, and Cheokas exclaimed, “I don’t know what the hell we’re going to do!” But Karloutsos shifted gears. “I said, ‘Do me a favor – let’s go for lunch to Le Pleiades.’ I ordered some great, great chicken and two bottles of wine. I love the French style chicken. And I told them, ‘Just go back and tell the President that the archbishop endorses it.’” The three of them were in shock, but Karloutsos said, “Look, the Ecumenical Patriarch wants Carter there. What are we worried about?” So Schira and Cheokas went back to Carter and told him that Iakovos favored the trip. Carter then instructed Schira to go on ahead to make arrangements.

Fr Karloutsos couldn’t keep Carter’s visit to Istanbul a secret from Iakovos for long. Once Schira was officially visiting the patriarchate on behalf of Carter, Iakovos would know that something was up. Karloutsos informed the archbishop during a car ride. “I said, ‘Your Eminence, President Carter has decided to go. He feels, since he’s in the region, he’d like to go to Constantinople.’ I did it in a nice way, but Iakovos was angry – he was seething – but he couldn’t express his anger. Iakovos said, ‘But I told him not to go. I think it’s the wrong thing.’ I said, ‘What can I tell you? That’s what they’re doing. And if President Carter is going, we’ve got to inform the patriarch, and you’re the one who has to do it. You’re the Exarch of North and South America.’ I’m driving along, and he’s ready to explode on me, but I’m driving.’”

But Archbishop Iakovos didn’t immediately call the patriarch. The next day, Fr Karloutsos called Metropolitan Bartholomew and told him about the Carter visit. The timeframe was pretty tight, and Carter’s people had to work with the Phanar to make the necessary arrangements. Karloutsos planned a trip with his family to Greece to coincide with Carter’s visit, and he intended to be with Carter in Corfu. Iakovos had other ideas. Karloutsos told me, “Two days before I was supposed to go to Greece with my wife and children, I received a phone call from Paulette Poulos, the archbishop’s secretary, saying, ‘Father Alex, you are forbidden from going to Greece when Jimmy Carter is there.’ Oh my gosh. In the meantime, my wife had broken her hand. So she said to me, ‘If you’re not going to go, I’m not going to go.’ And I said to her, ‘Honey, you’ve got to go, because if Carter senses that Iakovos is against this, he will cancel the trip.’ I needed my wife to be there to make sure that everything’s fine. So then I sent a message to President Carter saying that there’s an emergency at the archdiocese and Father Alex has to stay. And my wife went to Corfu and put our children with her aunt and uncle, and every day she would take care of Jimmy Carter and Rosalyn – she was actually their tour guide on Corfu and his interpreter on occasion. And she was my eyes and ears. And she had a broken hand.”

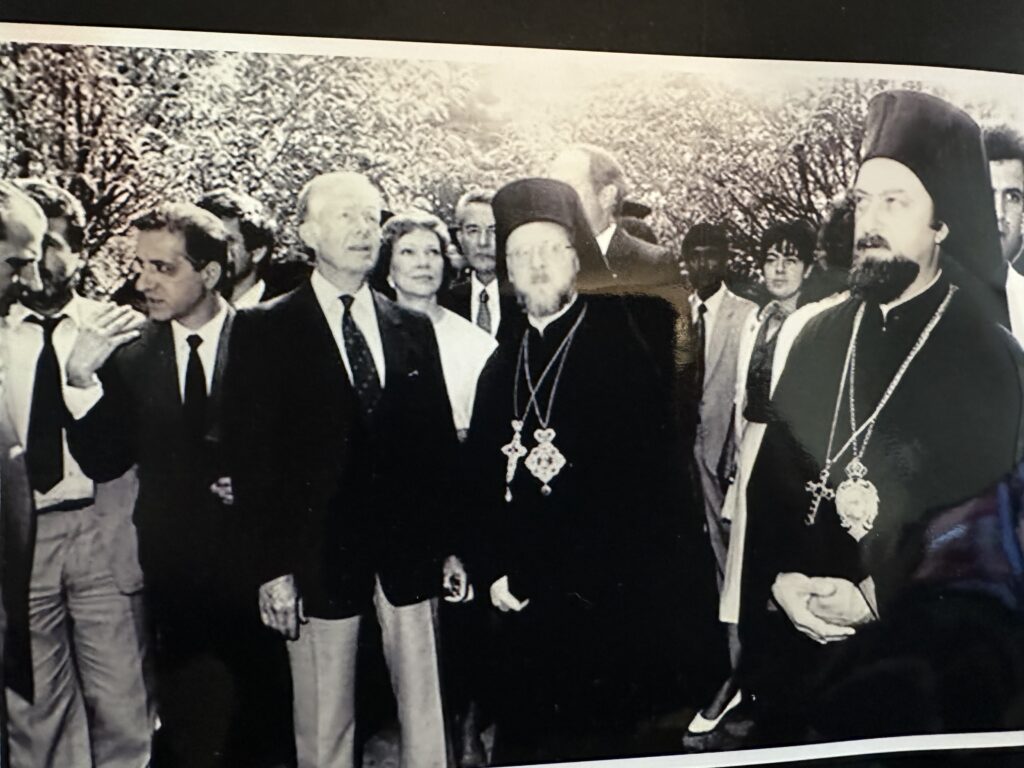

And so President Carter visited the Phanar, and Metropolitan Bartholomew showed him the burnt-out structure. Carter and Bartholomew walked on the burnt rubble and Carter promised to intercede with Turkish prime minister Turgut Özal on behalf of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. Carter assigned Schira the responsibility to work with the Turks until permission was granted. The Turks responded by giving the patriarchate its long-sought building permit, and Panagiotis Angelopoulos, a major philanthropist from Greece, funded the whole project.

Archbishop Iakovos may not have known the details of Fr Karloutsos’s role, but he understood well enough. “He tried to separate me from Bartholomew. He would speak suspiciously of Bartholomew to Patriarch Dimitrios, and to me he said, ‘You can no longer have relations with Bartholomew.’ But by that time, we had already become close friends.”

Metropolitan Bartholomew and the Oval Office

Although Iakovos’s trust in his priest was shaken, Fr Karloutsos’s skills and connections were so unique that the archbishop had little choice but to rely on him. In 1986, Iakovos put Karloutsos in charge of a struggling, fledgling foundation called Leadership 100, which was intended to be a major funding vehicle for the archdiocese. Karloutsos was perfect for the job, leveraging his connections in the philanthropic world to build the fund. “But it didn’t mean I had to give up the politics,” Fr Karloutsos told me. “In fact, it played out very well. I could use the politics and the money, which I did, and then, because I did great, I became part of Iakovos’s inner circle again – but he was always reminding me not to have a relationship with Bartholomew.”

By the end of the decade, Patriarch Dimitrios was well into his seventies, and the question of patriarchal succession was in the air. Iakovos, who had long kept a distance between the patriarchate and the American archdiocese, decided to make a calculated gamble: he invited Patriarch Dimitrios to visit the United States. “He didn’t think the patriarch would come,” Fr Karloutsos said. “At that time, the Turkish government prohibited travel, and Iakovos knew that. He invited him just to show that he is the great Iakovos – he never believed that he would come.” It was a sort of power move at a key moment. But the Phanar called Iakovos’s bluff, and Dimitrios accepted the invitation.

“So Iakovos had a meeting in his office,” Fr Karloutsos recalled, “and he said, ‘You won’t believe it – the patriarch is coming next year. He can’t speak English. We’re going to look Old World.’ And I’m sitting there listening, and I said to myself, ‘Geez, I know what I would do,’ but I didn’t want to speak up, because I wanted to think about things. Then I went to see Iakovos privately, and I said, ‘Your Eminence, there’s only one thing to do. We’ve got to keep him distant from the people so they don’t see any weaknesses, but they can look at him from a distance. Humility is holiness, and people want holiness. So we can keep him at a distance and raise him up above everybody else. But there’s one big problem: you have to humble yourself, because you’re the leader. If you humble yourself, everybody will follow your example.’ Iakovos said, ‘That’s a great idea. I’ll do it.’” Why would Iakovos, so careful to preserve his own position, do something like this? Fr Karloutsos explained, “Because down deep, he still has a love for the Church – plus, he’s now going to host the Ecumenical Patriarch for the first time in the history of the United States.”

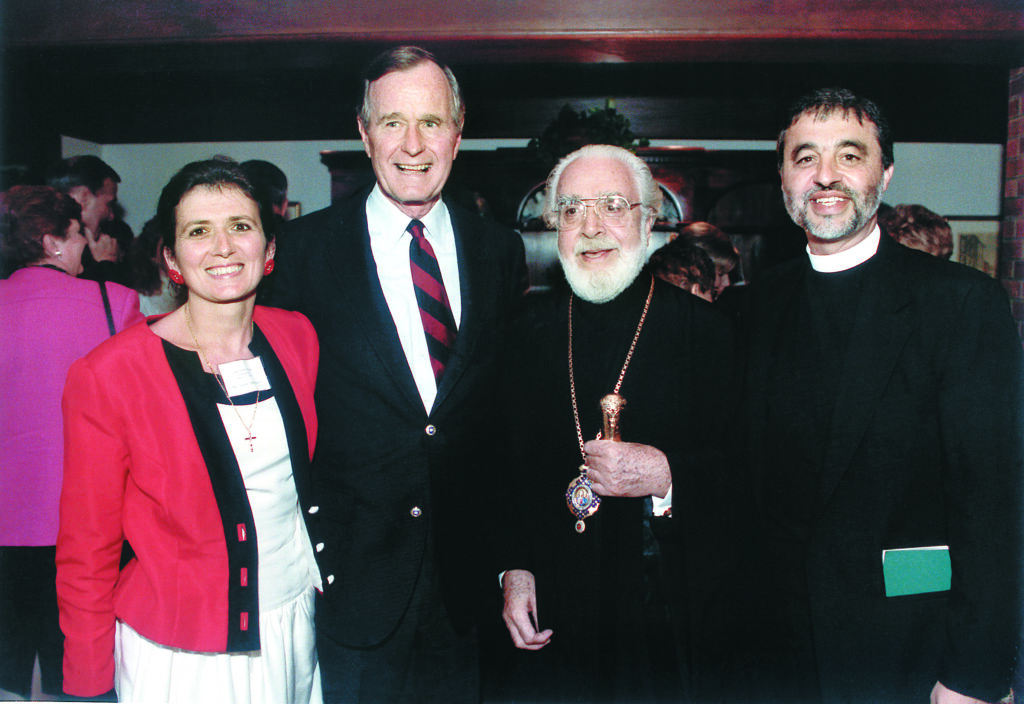

It was up to Fr Karloutsos to organize the visit. Metropolitan Bartholomew was part of the patriarchal entourage. “I got the Secret Service [for patriarchal security],” said Karloutsos, “I got [Nightline anchor] Ted Koppel to be the toastmaster, I had President George Herbert Walker Bush there. We had everybody. Andrews Air Force Base, private jet. I got the Capitol Rotunda closed down for him. The President was meeting him in the Oval Office and at a dinner at the State Department. He was received as a head of state.”

Fr Karloutsos was in his element. Patriarch Dimitrios was all set to have an audience with President Bush in the Oval Office, but on the eve of the meeting, says Karloutsos, “Archbishop Iakovos calls me into his room and said to me, ‘I want you to tell the patriarch that only me, him, Mr Angelopoulos [the philanthropist who had financed the rebuilding of the patriarchate], the patriarch, and his interpreter will be there. Go tell the patriarch that Bartholomew can’t come.’ I said, ‘But he’s already scheduled to be in the meeting.’ Iakovos told me, ‘Then you tell him that the White House called you and said that he can’t come.’”

Karloutsos now faced a difficult decision, a choice between his loyalty to Iakovos and his friendship with Bartholomew. It was his Rubicon moment.

“So I went in to see the patriarch and Bartholomew, and I said, ‘Well, I’ve got news for you. Archbishop Iakovos told me that the White House called and said that the meeting with the President is only for the patriarch, Archbishop Iakovos, Mr Angelopoulos, and the translator. No one else can come.’ He said, ‘Is that true?’ I said, ‘No, it’s not true. But he told me to tell you, so I’m telling you.’ So he asked, ‘What do we do?’ I said, ‘If I were you, I’d tell Iakovos to cancel the meeting.’”

Patriarch Dimitrios and Metropolitan Bartholomew were stunned – cancel a meeting with the President of the United States? But Fr Karloutsos knew what he was doing. “I said, ‘Yeah, because I know that at the end of the day, Iakovos won’t cancel. You’re calling his bluff.’ So the patriarch said, ‘Okay, go tell him.’ And I said, ‘Oh, no, you have to tell me to tell him to cancel.’ So he repeated, ‘Go tell Iakovos that we’re not going to go. If Bartholomew doesn’t come, I’m not coming.’ So I went back to Iakovos and he said, ‘What happened?’ I said, ‘He got really mad, and he said to cancel the meeting with the President.’ Iakovos said, ‘How can we cancel the meeting with the President?’ I said, ‘I don’t know what’s going on over there. Cancel the meeting.’ He said, ‘Okay, let Bartholomew come.’”

Karloutsos’s plan had worked. And his choice had been made.

The Patriarchal Election

Patriarch Dimitrios visited the United States in the summer of 1990. Meliton of Chalcedon died in December 1989, and Bartholomew succeeded his mentor as metropolitan of Chalcedon – a position that outranked Archbishop Iakovos’s see of North and South America. The close bond between Meliton and his disciples Bartholomew and Joachim was such that he actually gave his personal home to the two of them when he died.

Archbishop Iakovos could see that Patriarch Dimitrios’s end was nearing, and according to Fr Karloutsos, Iakovos attempted, through an intermediary, to pressure the patriarch to retire and give him the throne. Dimitrios was heartbroken – according to Fr Karloutsos, this was done in a harsh manner, and when the patriarch emerged, Bartholomew and Joachim found him weeping. Not long after this, on October 2, 1991, Patriarch Dimitrios died. Karloutsos described Metropolitans Bartholomew and Joachim as being embittered toward Iakovos for putting so much strain on the aged patriarch.

“Bartholomew wanted to become patriarch and Iakovos wanted to become patriarch,” Fr Karloutsos said. Karloutsos was now five years into a wildly successful tenure as head of Leadership 100, and he planned to bring a big delegation of Greek-American philanthropists to Dimitrios’s funeral in Istanbul. “So we filled up a plane, with Archbishop Iakovos leading the delegation. And we got a delegation from the White House – the first time in the history of the United States that a delegation representing the President attended the funeral of a patriarch. Now, Iakovos was setting himself up as the candidate, and I told him, ‘This would make you the leading candidate, Your Eminence. So this is the right thing for you to do. Show the strength of America, that you’re bringing these people over.’ He loved the idea. Then I got a phone call while he was in Switzerland, saying that Iakovos wants to become Ecumenical Patriarch, and they wanted me to handle the White House – they wanted Iakovos’s name imposed.”

Under Turkish law, all candidates for Ecumenical Patriarch must be preapproved by the governor of Istanbul. In the last election, 1972, the Turks had vetoed all the leading candidates, including Metropolitan Meliton and Archbishop Iakovos. This time, Iakovos wanted his name imposed, and he wanted Karloutsos to secure the American government’s support for this plan.

“I arrived in Istanbul,” Fr Karloutsos remembered, “and I got a phone call from Bartholomew. He says, ‘I’d like to see you. The driver will be in front of the Hilton.’ I had just left a meeting where the American power group, the money guys, were all pushing the idea that Iakovos was to become Ecumenical Patriarch. I’m in that meeting, I leave that meeting, I get in the car. It was a Mercedes, and he took me to this neighborhood. I didn’t know where I was. I knocked on the door, and a priest opened it. I went into the room and Joachim was there. We were talking, and then Bartholomew came in. And Joachim said to me, ‘Listen, we need help. The Turkish government will erase names. The number one candidate of ours is Bartholomew. Our geronda, Meliton, his name was erased, and three others, at the election after Athenagoras. We don’t want you to ask for anybody’s name to be imposed. What we want you to do is please help arrange for the Turks not to erase any names – for the Turkish government not to interfere in the election. If they erase Bartholomew’s name, I’ll be patriarch. But we don’t want anybody’s name erased and we don’t want anybody’s name imposed.’ I said to Bartholomew, ‘But people are saying, why don’t you come to America and let Iakovos come here, who’s the leading personality in the world – that might be the best way of succession.’ Joachim thought I was crazy when I said it, that I couldn’t be trusted at that point, because why am I saying that? Bartholomew knew that I was not that kind of a person, and said, ‘I love the patriarchate. Even if I’m going to be an assistant, I’m not going to America. I’ve got to stay where my heart is. So take that out of your mind. All that I want you to do is this. So I said, ‘You have my word, I’ll do that.’ When I told my wife about all that, she said, ‘You’re stupid.’ I said, ‘What do you mean, I’m stupid?’ She said, ‘Do you think that Iakovos, if he became Ecumenical Patriarch, would allow Bartholomew to go to America?’ I said, ‘Well, that was stupid.’ I told this to Bartholomew, and he said, ‘Listen to your wife.’”

Fr Karloutsos now had two conflicting assignments. “My task was then to make sure that the President knew that Iakovos wanted to be Ecumenical Patriarch, but he had to know that the policy should be not to impose anybody’s name or erase a name. So then, what did I do? I always keep my word.” He called a couple of Bush’s top advisors and told them that the policy should be not to erase or impose any names. National Security Advisor Brent Scowcroft agreed. Then Karloutsos went to a big-time Greek philanthropist, Alec Courtelis, and told him to call Bush directly and advocate for Iakovos. “But the position had already come out of the White House, not to erase or impose any names. So Bush told the philanthropist, ‘How can we impose Archbishop Iakovos’s name when we’re telling the Turkish government that they can’t erase anybody’s name? That’s our position. We’re not going to change that position.’”

Technically, Fr Karloutsos had done what both Iakovos and Bartholomew wanted – but the order was crucial. “There were two positions – I just arranged the one before the other. Then on October 20, I got a phone call to my home in New York. I was playing basketball in the backyard with my son Michael. My wife says, ‘Alex, Alex, the White House is on the phone! It’s somebody named General something.’ I took the phone. General Scowcroft said, ‘Father Alex, I want you to know that it was just confirmed that the Turkish government will send back the list without any names being erased.’ So I called up Bartholomew: ‘Your Eminence, I was just informed that they’re not erasing any names.’ Hopefully it’s true! Two days later, the Turkish government returned the list. No names erased.”

At this pivotal moment, Fr Karloutsos was in, not Istanbul, but New York. The reason is that he was helping the Orthodox Church in America arrange a landmark visit of Patriarch Alexei II of Moscow – a task he undertook with Metropolitan Bartholomew’s blessing. “I was in the car with [OCA chancellor] Bob Kondratick, on my way to LaGuardia airport, and my wife called me on my cell phone. She said, ‘Bartholomew is elected! Bartholomew is the patriarch!’ Oh, my God! So I went down to the State Department with Kondratick.”

Archbishop Iakovos, too, was in America at the time of the election. Fr Karloutsos insisted that Iakovos had to attend Patriarch Bartholomew’s enthronement: “He cannot look embittered, because they’re all going to say there’s going to be a division between them. I reached out to the White House, and they arranged, for the first time in the history of the United States, for a Presidential delegation to go to the enthronement of the Ecumenical Patriarch. And the President asked his brother, Bucky Bush, to represent him.” Bartholomew refused to accept a phone call from Iakovos, still bitter over his treatment of the late Patriarch Dimitrios.

The new patriarch wanted to hold his enthronement right away, just a few days after the election, but Fr Karloutsos convinced him to wait ten days, to give him time to organize the American delegation. “And he agreed to it,” Karloutsos said, “and that’s how we chose November 2.”

Karloutsos was responsible for picking up Bucky Bush from the Istanbul airport. “When I went to the airport to pick up Bucky Bush, the consul general told me, ‘I’m very happy for you, Father Alex.’ I said, ‘Why is that?’ He said, ‘Your man won.’ I said, ‘He wasn’t my man.’ He said, ‘We all know the same thing, the State Department, everybody knows. But you realize one thing?’ I said, ‘What’s that?’ He said, ‘People from the Phanar went to Ankara to erase Bartholomew’s name.’” This last statement showed the reach of Archbishop Iakovos and portended difficulties to come.

Exile

It is true that Fr Karloutsos’s man – his friend – had become patriarch – but his master, Iakovos, had not. This was the final straw. Archbishop Iakovos, who viewed Karloutsos as a traitor, gave him the cold shoulder for a few months, and after Pascha, he offered him a choice: either quit his job at the archdiocese, or be fired. Karloutsos quit. He was given three months’ pay and banned from serving anywhere in the archdiocese.

Unemployed and effectively suspended from the priesthood, Fr Karloutsos was in a dark place. He traveled to Istanbul and met in person with Patriarch Bartholomew. ‘I said, ‘Your All-Holiness, I did what I did because of my love for the Church. Now I’m in exile, and I know Iakovos will seek to destroy me. So what I’d like you to do is to ask for me to come to Constantinople and serve.’ He said to me, ‘You realize what you’re asking?’ I said, ‘Did you realize what you asked me to do with the Turkish government? I put my life on the line, and I don’t want to end up like other priests and go into business or become an executive or a multimillionaire. I want to live my life as a priest.’ He said, ‘Well, let me think about it.’ He spoke to Joachim, who was his conscience. And Joachim said, ‘You realize, having Father Alex here, what he could do for us? He opens up all these doors. Plus, we owe him.’ So the patriarch called me the next day and said, ‘I’m going to ask for you.’ Which was a big deal, because the greater did not ask the lesser.” Initially, Archbishop Iakovos refused to grant the release, but in the end he relented.

“For four years, I was in exile in Constantinople,” Karloutsos said. “I was maligned, I was called Benedict Arnold, because Iakovos controlled the narrative. It made me Public Enemy Number One. I was condemned by fellow priests, by lay people whom I helped. For four years, I was struggling, with my ego, with ‘who is Father Alex? Did I do the right thing? Did I serve the Church?’”

***

One day, in Istanbul, Fr Karloutsos was having lunch with Patriarch Bartholomew. “I don’t want to see you again until you read The Great Church in Captivity,” the patriarch said. Karloutsos had never encountered the famous Steven Runciman book on the Ecumenical Patriarchate under Ottoman rule. “Read the book,” Bartholomew told him, “and then we can have a conversation about your role in the Mother Church.”