No one knows for certain when and where the first Orthodox Divine Liturgy was served in Canada. The first documented Liturgy was served in June 1897 by the Seattle-based missionary Fr. Dimitri Kamnev (assisted by Vladimir Alexandrov, then a reader) in a field belonging to Theodore Nemirsky at Wostok, Alberta. At this Liturgy, approximately six-hundred Greek Catholics and others were united to the Orthodox faith. Nevertheless, local lore abounds about the presence of much earlier Orthodox activities spread out across the vast Dominion – now the most expansive territorial diocese in world Orthodoxy.

Unsubstantiated reports suggest that the Greek seafarer Ioánnis Fokás (a.k.a. Apóstolos Valeriános, or “Juan de Fuca”) may have brought his Orthodox faith with him in some sort of meaningful way as he explored the west coast of North America in 1592 for King Phillip II of Spain. The Strait of Juan de Fuca which separates Vancouver Island from the U.S. Pacific Northwest mainland is named for him. While precious little is known about Fokás’s own life and religious commitment, the mere presence of an Orthodox Christian explorer in the archipelagos adjacent to Alaska – more than two hundred years before the Valaam mission – is a historical episode that begs further study.

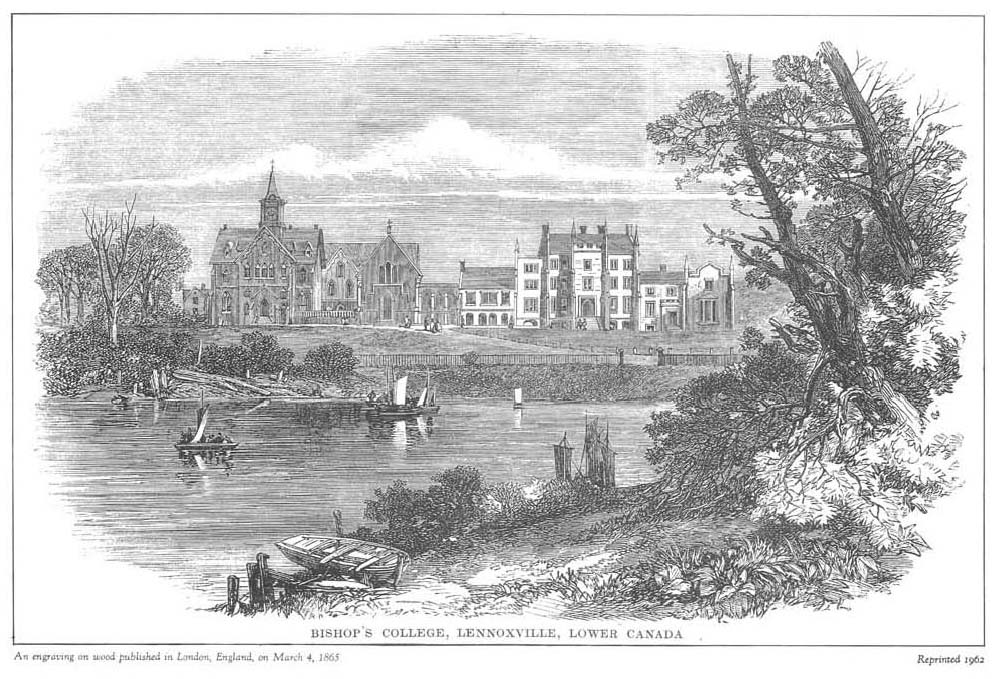

In an article entitled “110 years of missionary efforts in Canada” published in the Summer 2007 edition of The Orthodox Church, OCA Archivist Alexis Liberovsky mentions accounts of Orthodox activity in Quebec in the 1860s or 1870s. There is indeed historical evidence of Orthodox Syrian or Lebanese merchants in Quebec at this time, both in Montreal and in the ‘eastern townships,’ which were then primarily English-speaking. Little to no documentary evidence, however, indicates that any clergy-led Orthodox services actually took place during this time. The plot thickens. In 1879, Bishop’s College in Lennoxville, Quebec received a gift of a rare and valuable book, an 1862 edition of the 4th century Codex Sinaiticus. The letter accompanying the donation reads as follows:

November 11, 1879. To the Principal of Bishop’s College, Lennoxville, from the Russian Minister to the U.S. on behalf of the Emperor of Russia. Concerning the donation of the Codex Sinaiticus at the request of Mr. James Simpson.

The story, as it is often relayed in Orthodox circles is that this donation on behalf of Tsar Alexander II was in some way in thanks to the College for allowing Orthodox services to be held in their chapel. Bishop’s College, an Anglican school then primarily concerned with the formation of clergy, has a reputation for such hospitality. The mysterious aspect of the story, however, is that if indeed there were services held, no Orthodox clergyman is named, and the local newspapers have no record of such an event. If it did happen, this is strange, since such services would have been in the public interest – if only as a liturgical curiosity.

Could the story of Orthodox services in Quebec in the 1870s possibly be true? At the time, Orthodox clergy in the ‘lower 48’ were pretty thin on the ground. The See of the Diocese of the Aleutians and Alaska had only been transferred from Sitka to San Francisco in 1872, during the episcopacy of Bishop John (Mitropolsky). At the time of the gift of Codex Sinaiticus, there were certainly less than a half-dozen Orthodox priests in North America, outside of Alaska. The only priest based in the region, who could plausibly have served in Quebec during this time, would have been Fr. Nicholas Bjerring, pastor of the Russian chapel of the Holy Trinity in New York City. His metrical book which is preserved in the OCA archives, contains only records of sacraments performed by Bjerring at his New York Chapel, so cannot prove that he served in Quebec. The timeframe of the gift of Codex Sinaiticus and gaps of time in his documented record suggest the off-chance of his presence in Quebec. In 1877 and 1878, we know that Bjerring made a trip to St. Petersburg, and perhaps he travelled through Quebec to serve the Syrian Christians there en route from Europe to or from New York. Conjecture would be that Bjerring may have been informed of the existence of this community during his time in Russia, and made arrangement to visit them on his return voyage.

Not much more can be said conclusively about the stories of Orthodox services in Quebec in the 1870s. It remains possible that services were held in Lennoxville, at Bishop’s College, but this has not been proven. The letter provided with the gift of Codex Sinaiticus is equally mysterious, particularly because in 1879 there was, due to the controversial behaviour of the previous representative – Konstantin Katakazi – no formally appointed Minister of the Russian Empire to the U.S. The military attaché, Alexander Gorloff, served in this capacity, but it is unknown which official was responsible for the donation. The next Minister, Karl von Struve, was not appointed until 1882. It is not known who “Mr. James Simpson” was, either.

Anyone with further information on Orthodox activity in Canada prior to the 1890s, would be most welcome to provide details in the “comments” section below.

So, as Alexis Liberovsky stated in his 2007 article, “the documented historical roots of Orthodoxy in Canada can be traced with certainty to the late 1890s.” The intrepid missionary activity of Frs. Dimitri Kamnev and Vladimir Alexandrov in western Canada is an essential aspect of this story. The work of other missionaries, such as Fr. Michael Andreades, Fr. Jacob Korchinsky, and Igumen Arseny (Chagovstov) fill out the early days of Orthodoxy in Canada. Future articles will explore their contributions.

[This article was written by Deacon Matthew Francis.]

Just would like to like to the fascinating “Roots of Community 1896-1937: Archdiocese of Canada, Orthodox Church in America”

http://www.archdiocese.ca/exhibit/landandpeople.html

which has quite an array of things displayed with some historical narrative for those who would like to get an idea of Canadian Orthodox History.

At a earlier article, I posted some rudiments of the first Church/jurisdiction in the Canadian provinces (present day).

http://45.77.159.119/2009/08/the-first-churches-state-by-state/#comments

As to conjecture on the connections of Bjerring, St. Petersburg and Syria:”The Churchman,” v. 36 (Dec. 29, 1877)

“The Syrian Christians.—From the Moscow Diocesan Gazette we learn that in Syria, though peace exists, the Christian population is filled with alarm. The Druzes, in the absence of the greater part of the army, threaten to massacre the Christians. The Patriach of Antiocb, Hierotheus, has for some months past lived at Beyrout, fearing, in view of the threatening state of affairs, to return to Damascus. The duties connected with the Patriarchate at Damascus are attended to by Cyril, Metropolitan of Palmyra. The Gazette mentions, as a fact interesting to its readers, that not only were the Patriarch Hierotheus, and the Metropolitan Cyril personally known in Russia, the former having visited there when Archbishop of Mount Tabor, many years since, but that two other prelates in the patriarchate, Gabriel, Archbishop of Beyrout, and Agassius of Epiphania, had spent some time in Moscow. Gabriel had been archimandrite of the Antioch convent in that city, and Agassius, after being connected in a subordinate capacity with that convent, had taught for a time in the Spiritual academy at St. Petersburg.”

http://books.google.com/books?id=fCDnAAAAMAAJ&pg=PA745&dq=churchman+Syrians+Hierotheus+Damascus&cd=1#v=onepage&q&f=false

The first person in Canada to research the history of Orthodoxy in Canada was the late Senator Paul Yuzik of Saskatchewan. Before he was appointed to the canadian senate he was a professor at the University of Ottawa. His doctorate was in history.

Currently the expert is Professor Daniel H. Sahas, University of Waterloo. Professor Sahas is a member of the Greek Orthodox Church of Canada, the largest jurisdiction in Canada.