Years ago, on an online database, I came across an article titled “The Two Greek Youth” and published in the April 1823 issue of The Guardian, or Youth’s Religious Instructor, a short-lived American magazine. According to the article, Protestant missionaries brought these two boys over from Malta to study at the Cornwall School in Connecticut.

One of the boys, Anastasius Karavelles (age 11) was the son of an Orthodox priest. Anastasius was born at Zante (Zakynthos), but the family moved to Malta when he was a small child. The other boy, Photius Kavasales, was a 15-year-old orphan who had lost almost his entire family (parents and six siblings) to the plague in Smyrna nine years earlier. He lived in a hospital for a few years, and when he was about 11 he was sent to live with an uncle in Malta. This uncle gave the Protestant missionaries permission to bring Photius to America.

According to the magazine, the boys both knew Greek, Italian, and Maltese, and before starting classes at the Cornwall School, they planned to spent time in Salem, Mass. and study English. The brief magazine article closed with a fundraising plea: “It may be proper to add, that their only dependence for support is upon the charity of the public — it is hoped that a generous sympathy will be felt for them, not only upon their own account, but on account of their oppressed and bleeding nation.”

Ah, yes, that’s right — this was smack-dab in the middle of the Greek War of Independence. Malta had become a part of the British Empire in 1819, but even so, the war in Greece must have placed some part in the boys’ (and their guardians’) thinking.

In any event, I always wondered, what happened to those boys? Is it even possible to find out, nearly 200 years after the fact, what became of a couple of Greek foreign exchange students from the 1820s?

To my surprise, it was kind of ridiculously easy. Do a quick Google search for “Photius Kavasales,” and you’ll find an act of the United States Congress dated May 3, 1848, authorizing the change of Navy chaplain Kavasales’ name to “Photius Fisk.”

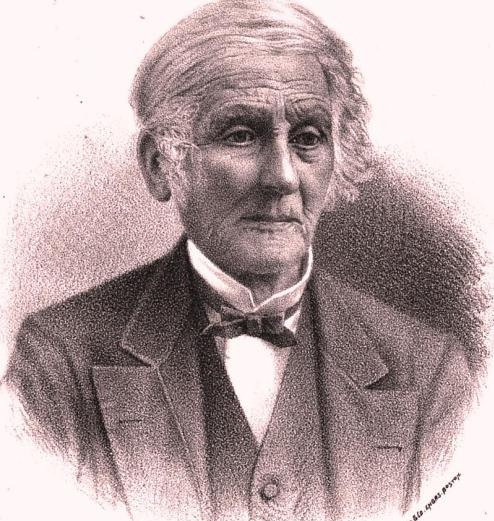

Why Fisk? Because a certain Rev. Pliny Fisk was young Photius’ patron. In 1891, a biography of Photius Kavasales Fisk was published, written by Lyman F. Hodge, and it’s chock-full of information, including a lengthy letter from Rev. Fisk himself. (The entire book is available on Google Books.)

Apparently, Rev. Fisk was working as a missionary at Malta when, in the summer of 1822, he ran into the teenage Photius and invited him to attend the mission’s Sunday School. Photius turned out to be a star student, and Fisk invited him to come to America and receive a full education. Photius’ uncle agreed, and everything was arranged.

As all this was happening, one of the local Orthodox priests, Fr. John Karavelles, asked about the possibility of sending his son Anastasius to America as well. Of course, the Protestants thought this was a fabulous idea, and both boys were signed up. Here’s how Lyman Hodge describes what happened next, in his biography of Photius:

Having been .associates and playmates from the time that Photius came to the island, the boys had become fast friends; and Mr. Fisk had promised that they should be kept together, and should be instructed in the same schools. But, in order to unite them in still closer and more endearing relationship to each other, they were made brothers, through the impressive ceremonies of the Greek Church. Clad in his sacerdotal robes, the priest, after an appropriate address to the two boys, bound them together with a girdle, and laying his sacred hands upon their heads, he solemnly pronounced them brothers, and declared that the bonds of relationship were indissoluble.

This rare and little known ceremony, called “adelphopoiesis,” is a sacramental rite to make two men brothers. That’s what the term literally means, and it’s how the ceremony has been used in the Orthodox Church from time immemorial. Not too long ago, a Yale historian came up with the idea that adelphopoiesis wasn’t actually about making men brothers, but rather that it was a rite of same-sex marriage. This theory had the lovely features of lacking any historical foundation whatsoever and simultaneously appealing to modern trends, so it’s gotten some unwarranted attention, but it’s been successfully rebutted by both Orthodox and secular scholars.

Anyway, Photius and Anastasius were made brothers, and they sailed for America. After completing their studies, both young men returned to Greece. Anastasius remained there, but Photius loved America and soon returned. He became a Congregationalist clergyman, eventually changed his name to Photius Fisk in honor of his patron, and had all kinds of interesting adventures that you can read about in Lyman Hodge’s book.

After Photius returned to America, he didn’t see Anastasius again for almost half a century. The two were briefly reunited when Photius visited Greece in 1871. Anastasius had done quite well for himself: according to the Biographical Record of the Alumni of Amherst College, after returning to Greece he had studied law, become a judge, and worked as director of telegraphs at Syra, Greece. After the visit, Anastasius wrote a touching letter to Photius:

I received with the greatest pleasure your portrait and the Park Street views. I am very sad that I have not been able to fulfil my promise to you to go to Athens. I am a slave to a miserable salary, and consequently not free to do according to my wishes. We are not brothers by necessity, but by our own choice and circumstances. We left Malta when boys together, and with the same hopes ventured the great ocean of chance to find a home and happiness. Fortunately, we are both safe from the danger of destitution in this life. We had the happiness to see each other, separated as we had been by oceans. We may see each other again,— God knows. The early impressions of our boyhood have been indelibly fixed upon our minds and hearts. We have loved each other truly and fraternally. My dear Photius, remember me ever, as I will remember you. If idolatry is a sin, I will commit that sin in remembering you always; and, seeing your portrait, I will love you sincerely to the end of my life.

Mrs. Karavelles and my children desire to unite with me in expressing their sincere thanks to you for the love you bear to me, and participate in this proffered love. Please write to me how long you intend to remain in Athens, and if you intend to come again to Syra.

I remain yours, truly and sincerely,

A. Karavelles.

Photius died in February 1890, at the age of about 83. I’m not sure when Anastasius died, but it was before Photius; the aforementioned book on Amhearst College alumni was published in 1883, and Anastasius had already been dead for “several years.”