Yesterday, we began publishing a series of excerpts from Matthew Spinka’s 1935 article on worldwide Orthodoxy in the years following World War I, originally published in the journal Church History.Spinka’s article is a succinct and quite balanced summary of the state of affairs in global Orthodoxy in a very chaotic period. From the standpoint of Orthodoxy in America, it helps a great deal to understand just what the Orthodox climate was like in this era. As I noted yesterday, this was precisely the time when national ethnic jurisdictions were being established in North America. A better understanding of the global Orthodox situation will help us to put the American situation in its proper context.

What follows is the section of Spinka’s article dealing with the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

To begin, then, with the group of Greek churches, we may first of all turn our attention to the patriarchate of Constantinople, the lineal descendant and heir of the Byzantine church. But this body, which had survived the fall of the Byzantine Empire and despite the prolonged misery and degradation suffered under the Turkish reign, had exercised ecclesiastical and civil sway over territories co-extensive with the Turkish Empire, scarcely escaped a total destruction when the new nationalist Turkey was set up by Mustapha Kemal Pasha. When the Kemalists refused to accept the Sevres treaty and in the end raised a standard of revolt even against the sultan himself, Greece, under the leadership of King Constantine, ventured to attack the embattled hosts of the Turkish nationalists, a megalomaniacal venture which ended in a complete fiasco and cost the king his throne. The Greeks of the patriarchate remained loyal to Venizelos, thus antagonizing King Constantine; but despite this, they could not altogether refrain from following with patriotic pride or solicitude the fortunes of the Greek armies in Anatolia. Although Turkish subjects, they held commemorative services for the fallen, collected contributions for the war cause, and openly espoused the Hellenic “grand idea” of restoration of the Byzantine Empire.

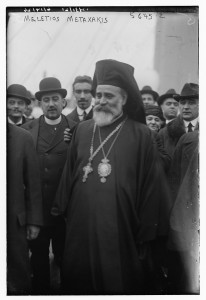

It was under these conditions that the patriarchal see, vacant since 1918, was filled in 1921 by the election of the former Archbishop of Athens, Meletios. But the new patriarch’s enthusiastic espousal of the Hellenic cause made his tenure of the patriarchal see quite impossible. After the debacle of the Greek armies in the disastrous battle of the Sakaria River in the autumn of 1922, Meletios’ situation became desperate. The victorious Turkish nationalists openly announced their intention of wholly abusing the ecumenical patriarchate, regarding it as a perpetual source of anti-Turkish agitation. At the Lausanne Conference in 1923, the British commissioner, Sir Horace Rumbold, had to exert all his diplomatic ingenuity to forestall the radical measure insisted upon by the Turks. In the end, the patriarchate was permitted to exist, but it was shorn of all the civil jurisdiction over the Greek community which it had exercised for the past four centuries, and its functions were restricted to purely ecclesiastical ones. But in the matter of Patriarch Meletios’ deposition, the Turkish delegation remained adamant. He had to go.

Beside these measures, the Lausanne Conference adopted a plan of forcible exchange of population between Turkey and Greece, from which none but the Greeks established in Constantinople and its immediate environs prior to October, 1918, were exempted. The exodus of the Christian population of Asia Minor in the wake of the defeated Greek armies as well as the forcible expulsion of the rest, in accordance with the population exchange measure, had a disastrous effect upon the ecumenical patriarchate; in fact it all but ruined it. Only four metropolitanates out of forty-one survived the measure, some of the ruined sees having been among the most ancient and celebrated, with traditions which went back to the times of Paul. The Orthodox population of Asia Minor and Thrace, which in 1914 had numbered 1,800,000, was reduced to between thirteen and twenty per cent (the church claiming 350,000, but the official Turkish count reporting 250,000). Even this number is continually dwindling, for the Greek population is moving out of Turkey. Thus the numerical strength of the ecumenical patriarchate has been so radically reduced that it now ranks among the smallest of the Orthodox communions.

The present patriarch, Photius II, who was elected in 1930, was able to establish a precarious modus vivendi with the Turkish government. Just because of the great diminution of the power and extent of the ecumenical patriarchate within Turkey, it strives with great earnestness to preserve for itself the traditional privileges inherent in its honorific status as the “primus inter pares” among the Eastern Orthodox communions. In this endeavor it has often exceeded its authority in acting as judge and arbiter in the various disputes or administrative changes which have taken place among the different Orthodox communions, over which, strictly speaking, it has no jurisdiction.

Next, we’ll publish Spinka’s discussion of the other “Greek churches” — the Church of Greece and the Church of Cyprus.

This snapshot misses the Pan Orthodox Congress of 1923 under Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios Metaxakis. There are two recent books by Fr. Patrick Viscuso on this important council, “Quest for Reform of the Orthodox Church: The 1923 Pan-Orthodox Congress: An Analysis and Translation of Its Acts and Decisions” and “Vested in Grace: Marriage and Priesthood in the Christian East”. Disclosure, I wrote an article and bibliography in the Vested in Grace book.

The impact of this council on Orthodoxy in America was substantial. First, three of the attendees were primates of Orthodox jurisdictions in America at various times. Patriarch Metaxakis was the primate of the Greek Archdiocese, Bishop Nemolovsky with the primate of the Russian jurisdiction, and Archbishop Anatassy later would become the primate of the Russian Synod in Exile. This congress authorized the use of the new calendar and the remarriage of Orthodox priests. What is not known is that this Congress condemned the “Living Church” then propped up by the Soviet regime. The recognition of the Living Church by Ecumenical Patriarchate happens after this congress. However for decades Russian church diplomats despised the Ecumenical Patriarchate for recognizing the legitimacy of the Living Church. It would be interesting piece of historical research to find out how extensive was the Russian Living Church phenomenon in the 1920s in America outside of their cathedral church on 97th Street in Manhattan.

Considering the intense passions and lawsuits here in America regarding the new calendar, it is a surprise that so few Orthodox know anything about the Congress of 1923.