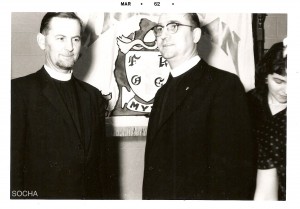

Several weeks ago, I saw a small news item on my Facebook timeline advertising the latest issue of Wonder, the Orthodox Church in America’s youth-oriented newsletter. I was slightly bemused that the item’s thumbnail picture was photograph I used as a centerpiece of a SOCHA piece I wrote last year about a visit Fr. Alexander Schmemann made to Detroit in 1962.

Several weeks ago, I saw a small news item on my Facebook timeline advertising the latest issue of Wonder, the Orthodox Church in America’s youth-oriented newsletter. I was slightly bemused that the item’s thumbnail picture was photograph I used as a centerpiece of a SOCHA piece I wrote last year about a visit Fr. Alexander Schmemann made to Detroit in 1962.

What I didn’t reveal last year when I shared this picture with our readers is that the man at Fr. Alexander’s left is my late grandfather, Fr. Ioann Sviridov, who was a deacon at the time the picture was taken.

What captured my attention the most was not that Wonder reused this photograph without citation, or even that its editors cropped out the SOCHA watermark I added in order to discourage this very thing. Rather, it’s the content of the article it is now paired with, a rather thought-provoking piece by Fr. Michael Koblosh about parish life in the Metropolia in the decades it was granted its autocephaly. The article’s content, paired with my grandfather’s likeness, presents a certain irony I cannot ignore.

Fr. Michael’s main argument concerns the important work of the Federated Russian Orthodox Clubs (FROC) during his childhood, which helped to bolster interest in English-language Orthodox publications and the use of English in worship. The central point of his article is the phrase “Orthodoxy is not here by accident,” which Fr. Michael heard at an FROC convention in the 1950s. He then claims these immigrants “probably would not have understood the meaning or implication of those words.” After all, in Fr. Michael’s recollections, these immigrants were relatively uneducated, often illiterate members of parishes where “intellectual life… was weak or non-existent.”

My grandfather was one of these Russian Orthodox immigrants. He came to the United States in 1928 as a literate, curious, and enthusiastic teenager who aspired to one day become an Orthodox priest. His father and brother were literate. So were his mother and youngest brother, who stayed behind in the Soviet Union. From his earliest years in America, the center of my grandfather’s life were his Russian Orthodox parishes in Detroit and St. Louis, though it can be argued that this was only rivaled by his desire to pursue his education.

My grandfather was one of these Russian Orthodox immigrants. He came to the United States in 1928 as a literate, curious, and enthusiastic teenager who aspired to one day become an Orthodox priest. His father and brother were literate. So were his mother and youngest brother, who stayed behind in the Soviet Union. From his earliest years in America, the center of my grandfather’s life were his Russian Orthodox parishes in Detroit and St. Louis, though it can be argued that this was only rivaled by his desire to pursue his education.

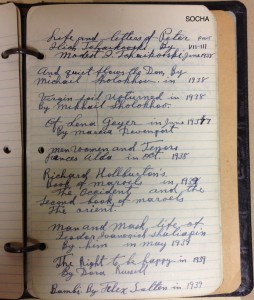

In the late 1930s, while working full time, he spent his evenings attending night high school classes in the St. Louis Public Schools, and also trained as an opera singer. During those years, he meticulously recorded the title of every book he read on page after page of his looseleaf notebook, ranging from classic novels to Greek mythology to history. When he entered the US Army in 1942, he had just earned a final grade of 95% in his eighth term of high school English.

After the war, as a husband and new father with a full-time job as a master electrician, he trained every evening with a local Russian professor so that he could be ordained a deacon. In this era, there were no “late vocations” seminary programs or summer deacons’ workshops. For men like my grandfather who entered adulthood in the 15-year gap between the 1923 closure of St. Platon Seminary and the opening of both St. Vladimir’s and St. Tikhon’s Seminaries in 1938, many of whom also served in the armed forces, there were no easy options to pursue a theological education in postwar America.

Like so many others, my grandfather had to work hard outside normal academic channels to achieve his goals. This meant late-night sessions most evenings with a local Russian professor, and periodic trips to Chicago to train with Bishop John (Garklavs). And it worked. The 1962 picture with Fr. Schmemann was taken five years after his ordination to the diaconate, and a year before he was finally ordained a priest at the age of 53.

My grandparents met in the Detroit church choir my grandfather conducted after he returned from the Second World War. My grandmother’s parents were also the immigrants Fr. Michael refers to. Both were literate. My great-grandfather was a machinist and supervisor at the Ford Motor Company’s River Rouge plant. His wife was a spirited and intellectually curious homemaker. Her brother was a blue-collar worker and amateur playwright, whose plays were enthusiastically performed in the parish hall. (Attentive readers may recall that I have written about my great-grandparents before.)

Three of the their four children who survived into adulthood graduated from college at a time when US Census data suggests more than half of all Americans never even finished high school, and less than ten percent finished college. Their church friends, most of whom also attended church-run Russian School most weekdays, grew up to be doctors, lawyers, teachers, secretaries, executives, skilled tradespeople, and small business owners. Throughout their lives, the center of their lives was their neighborhood parish, not to mention its “R” Club.

As a historian, I mostly focus on these generations of immigrants, who molded communities like the one Fr. Michael describes in his article for Wonder. My research into these immigrant communities, not to mention my family’s own history, indicates that the first waves of immigrants lived their religious lives in complex ways that may not necessarily coincide with how modern-day Orthodox Christians live their own.

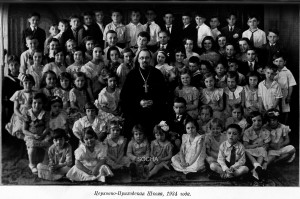

My findings suggest that even in the earliest decades of mass emigration, many Russian immigrants in major urban centers were not only literate—they were often reading newspapers in multiple languages. They went to night school, attended evening lectures and plays, and eagerly sent their children to school—usually both American public schools and after-hours “Russian School.” As early as the 1920s, extant data suggests there were well over a hundred of such church schools in operation, many of which were still open well into the 1960s.

Russian Orthodox parishes were also vibrant centers of cultural and creative activity. Parishes frequently sponsored musical ensembles, theatrical troupes, and dance ensembles. These were seen as important touchstones of immigrants’ religious lives and points of communal pride, inseparable from parishes’ liturgical and sacramental activities.

My point is to suggest that while Fr. Michael’s observations may be valid to his own experience growing up in upstate New York, pointing to the lack of English-language books about Orthodoxy and projecting blanket observations about literacy onto a national church body invites subjective value judgments about the past that, in my view, are misleading, if not inaccurate. Bluntly, to state that intellectual life in early twentieth century Russian parishes was “weak or non-existent” is not a fair assessment.

The irony that my grandfather’s image appears alongside an article that so distorts not only his experience, but also those of many of his generation, only underscores my belief that a telling of Orthodox history in North America must be undertaken with greater sensitivity and accuracy. We must recognize that blanket statements and assumptions that obliterate the striking complexities and diverse agencies found within Orthodox immigrant communities during the early twentieth century distort their place in the historical record. Marginalizing historical actors to inspire future generations is a disservice to all involved.

While I recognize that Fr. Michael was probably not consciously writing as a historian, and was certainly not writing for an academic audience, it is still imperative that those who write about the past do so carefully and judiciously. We must take into account that speaking for those who can no longer speak for themselves comes with an expectation that our accounts and interpretations of their lives are accurate, sensitive, and fair. For those of us with a direct connection to that past, it should not be necessary to sell our ancestors short in order to suggest a more enlightened present. Plainly, we can—and must—do better.

Aren’t we overreacting a bit to Fr. Michael’s recalling that “many of the immigrants were practically illiterate”? I’m a professional historian (though I’m Orthodox, Church history is not my discipline), and we have to respect the memories and recollections of people who were actually there, while of course placing those memories in historical context. I’ll bet Fr. Michael would agree that many immigrants were highly educated, too.