Last night, March 1, 2015, the brilliant Orthodox scholar (and priest, husband, and father of six), Fr Matthew Baker, died in a car accident. In remembrance of him, we are republishing a really outstanding article that he wrote for this site in 2012. You can read more about Fr Matthew in this post by his friend, Fr Andrew Damick. If you are able, please consider making a donation to help Fr Matthew’s wife and children, at this link.

Last night, March 1, 2015, the brilliant Orthodox scholar (and priest, husband, and father of six), Fr Matthew Baker, died in a car accident. In remembrance of him, we are republishing a really outstanding article that he wrote for this site in 2012. You can read more about Fr Matthew in this post by his friend, Fr Andrew Damick. If you are able, please consider making a donation to help Fr Matthew’s wife and children, at this link.

Sixty-five years ago today, on Holy Monday, April 7, 1947—the feast of Annunciation (O.S.)—an important event in the history of Orthodoxy in America occurred, with the first visit of Father Georges Florovsky to the United States. As with so many key turns in his ecclesiastical trajectory, Florovsky’s coming to America was occasioned by his intense involvement in the ecumenical movement.

The general plan to establish a World Council of Churches (WCC) had been agreed upon at the meeting of the Faith and Order Movement in Edinburgh, 1937, where Florovsky was present together with Fr. Sergii Bulgakov. While Florovsky himself had at this point yet no official standing as an Orthodox representative within Faith and Order, he was on this occasion elected to the “Committee of Fourteen,” composed of seven representatives of Faith and Order and seven of Life and Work, whose task it was to organize the future World Council of Churches. Given that the Orthodox representative for Life and Work was Metropolitan Germanos (Strinopoulos) of Thyateira and Great Britain, it was felt that the other Orthodox representative should be a non-Greek. The likely candidate was Fr. Sergii Bulgakov, who was both senior to Florovsky and had also been involved in Faith and Order since its inception at the Lausanne Assembly of August 1927.

Bulgakov, however, had recently drawn controversy for his sophiological teaching. And of the two, Florovsky had the greater facility with the English language. In all likelihood for these reasons, both the Orthodox and the Anglicans and American Episcopalians, who were responsible for funding much of the scholarly and ecumenical activity of the Orthodox centered at the Institute St. Serge (Paris), chose Florovsky instead, considering him the more trustworthy representative of Orthodox theology. According to Florovsky’s own unpublished account, it was Metropolitan Antony Bashir, also present at Edinburgh, who informed him of this decision. The reason Antony gave is interesting: it was because the “American Orthodox” wanted him.

The preparation of the World Council of Churches, however, was deferred by the Second World War. Florovsky was in Geneva at the outbreak of the war, unable to return to Paris, and therefore spent the whole of World War II in exile: in Yugoslavia (December 1939 to October 1944), serving as a chaplain and religion teacher at two high schools for Russian boys and girls; and then finally in Prague, teaching English and engaged in extensive pastoral work among the Russian emigres. Only in December 1945 was he able to return to Paris and resume his pre-war scholarly and ecumenical activities, commuting frequently throughout 1946 and 1947 to Geneva for meetings in preparation for the WCC. It was at this point that the stage was set also for his visit to the U.S. A meeting of the provisional committee of the WCC was planned to be held in America, Spring 1947. As a member of the committee, Florovsky was invited.

The preparation of the World Council of Churches, however, was deferred by the Second World War. Florovsky was in Geneva at the outbreak of the war, unable to return to Paris, and therefore spent the whole of World War II in exile: in Yugoslavia (December 1939 to October 1944), serving as a chaplain and religion teacher at two high schools for Russian boys and girls; and then finally in Prague, teaching English and engaged in extensive pastoral work among the Russian emigres. Only in December 1945 was he able to return to Paris and resume his pre-war scholarly and ecumenical activities, commuting frequently throughout 1946 and 1947 to Geneva for meetings in preparation for the WCC. It was at this point that the stage was set also for his visit to the U.S. A meeting of the provisional committee of the WCC was planned to be held in America, Spring 1947. As a member of the committee, Florovsky was invited.

Other developments were taking place during this same time that would be determinative both for Florovsky’s future and that of Orthodoxy in America. In November 1946, the Seventh All American Church Sobor of the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America (the “Metropolia”) was held in Cleveland, Ohio. At the request of Metropolitan Theophilus (Pashkovsky), plans were drawn up for the re-formation of St. Vladimir’s Seminary (founded in 1938) into a real theological academy, on the model of the four pre-revolutionary Russian academies. At the suggestion of the historian George Fedotov, a colleague from St. Serge who had come to teach at St. Vladimir’s in 1945, Florovsky was named as the choice for professor of dogmatics and patrology.

The meeting of the provisional committee was held in Buck Hill Falls, Pennsylvania, on April 22-25, 1947. There it was announced that the first Assembly of the World Council of Churches would be held at Amsterdam from August 22 to September 5, 1948, having as its general theme “Man’s Disorder and God’s Design.” It is perhaps indicative of Florovsky’s influence that, already at this point, the WCC’s general secretary W. A. Visser’t Hooft emphasized to the press that the WCC was not to be understood as a “super-church” which would dictate to its member bodies, but only “an expression of the desire of the Churches to obey the will of their common Lord,” involving “not . . . the denial of the confessional heritage of the churches,” but rather “the attempt to manifest that unity which has actually been given to churches that take their confessions seriously” (“Progress Report for the World Council: Provisional Committee Holds First Meeting in United States,” Federal Church Bulletin, Vol. XXX, No. 5, May 1947, 6-7).

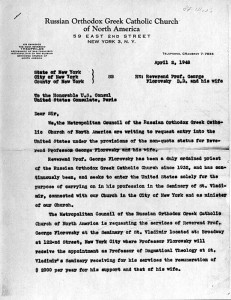

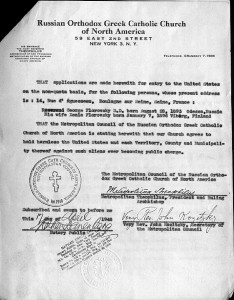

Following the conclusion of the provisional committee meeting, Florovsky traveled to New York in May 1947 to discuss the possibility of his coming to teach at St. Vladimir’s. The seminary was at this time housed in a cottage owned by General Theological Seminary (Episcopal Church USA), and had only a dozen students and limited faculty and resources. Florovsky spent most of his visit with Metropolitan Theophilus. The result of their conversations was that Florovsky agreed to accept appointment to the faculty, with the tacit understanding that he would later take up the deanship. Theophilus and Florovsky saw eye to eye both on the need to develop high-level theological education for clergy and to introduce the English language into teaching and church services. Almost exactly a year after Florovsky’s visit, on April 2, 1948, the Metropolitan Council of the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America sent a letter to the American consulate in Paris requesting the entry of Florovsky and his wife into the US under non-quota status. Florovsky would later become a naturalized American citizen in 1954.

Following the conclusion of the provisional committee meeting, Florovsky traveled to New York in May 1947 to discuss the possibility of his coming to teach at St. Vladimir’s. The seminary was at this time housed in a cottage owned by General Theological Seminary (Episcopal Church USA), and had only a dozen students and limited faculty and resources. Florovsky spent most of his visit with Metropolitan Theophilus. The result of their conversations was that Florovsky agreed to accept appointment to the faculty, with the tacit understanding that he would later take up the deanship. Theophilus and Florovsky saw eye to eye both on the need to develop high-level theological education for clergy and to introduce the English language into teaching and church services. Almost exactly a year after Florovsky’s visit, on April 2, 1948, the Metropolitan Council of the Russian Orthodox Greek Catholic Church of America sent a letter to the American consulate in Paris requesting the entry of Florovsky and his wife into the US under non-quota status. Florovsky would later become a naturalized American citizen in 1954.

After his visit to Pennsylvania and New York in spring 1947, Florovsky returned to Europe. The First Assembly of the World Council of Churches took place in Amsterdam on August 22 to September 4, 1948, with some 14,000 persons present. Here, together with his friend the Anglican priest Michael Ramsey (who would become Archbishop of Canterbury in 1961) and the Swiss Reformed theologian Karl Barth, with whom he shared a common resistance to political pragmatism in ecumenical relations, Florovsky emerged as the leading theological voice. He was at this time elected also to the executive committee of the WCC.

Just ten days after Amsterdam, on September 15, 1948, Florovsky left Europe for good, arriving in New York by boat on September 21 to begin teaching at St. Vladimir’s. A year later, Florovsky took over the acting deanship from Bishop John Shahovskoy, and in 1950, he was officially made dean. He was to remain in that capacity until 1955. During his tenure at St. Vladimir’s, Florovsky raised academic standards and introduced the English language, placing the seminary on the map as an important center of theological education and injecting a crucial missionary dimension to its outlook.

Florovsky’s 1947 visit to America was therefore an event which both foreshadowed and helped to prepare two important developments in Orthodoxy and the Christian world at large: first, the formation of the World Council of Churches, and the presence of a powerful Orthodox theological voice within it; and second, the development of an articulate and missionary-minded Orthodox theology on American soil.

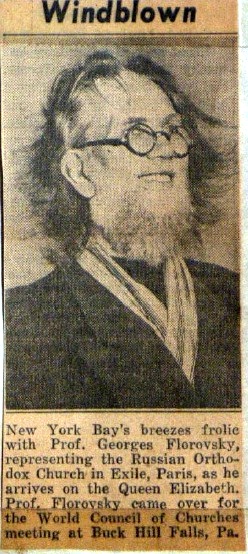

Photographs of Florovsky’s arrival in New York Harbor on April 7, 1947, published in The New York Times and Newsweek have a certain strangeness and wonder about them, marking the distance from his time and situation and our own. That the visit of any theologian—not to mention, Orthodox—would be considered worthy of feature in a major news source bespeaks a bygone age when Christian churches and theology still wielded a certain recognized cultural authority. That epoch gasped its last some time after the media excitement of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). It is perhaps significant that, with the sole and recent exception of Pope Benedict XVI, no theologian has appeared on the cover of Time magazine since the April 20, 1962, feature of Karl Barth. It is hard to imagine a photograph of any leading Orthodox theologian today being featured within the pages of Time, Newsweek, or The New York Times, as Florovsky himself was in the 1940s and ’50s.

Photographs of Florovsky’s arrival in New York Harbor on April 7, 1947, published in The New York Times and Newsweek have a certain strangeness and wonder about them, marking the distance from his time and situation and our own. That the visit of any theologian—not to mention, Orthodox—would be considered worthy of feature in a major news source bespeaks a bygone age when Christian churches and theology still wielded a certain recognized cultural authority. That epoch gasped its last some time after the media excitement of the Second Vatican Council (1962-65). It is perhaps significant that, with the sole and recent exception of Pope Benedict XVI, no theologian has appeared on the cover of Time magazine since the April 20, 1962, feature of Karl Barth. It is hard to imagine a photograph of any leading Orthodox theologian today being featured within the pages of Time, Newsweek, or The New York Times, as Florovsky himself was in the 1940s and ’50s.

The modern ecumenical movement was itself conceived initially as a missionary response to an era of intense secularization. Doubtless, it was spurred on also by a humanitarian reaction to two massive wars, in which men of different countries equally confessing the name of Christ spilled one another’s blood over nationalist interests. Yet the early ecumenical movement came to birth nevertheless with a hope and confidence among some Christian leaders that a soundly Christocentric theology might matter still, and be heard by more than a few. With all their crucial differences, leading ecumenical figures of this period such as Florovsky and Barth were united at least in their attempt to respond to “man’s disorder,” not with humanitarian bromides regarding “tolerance” and “diversity,” or demi-Marxist clarions to class struggle, identity politics, and statist social planning, but with a word about creation, sin and redemption: the good news of Christ and his Church.

In “The Church and Her Responsibility,” a paper written for the Faith and Order Study Commission “The Universal Church in God’s Design” in March 1947, just a month before his visit to America, Florovsky stressed that the primary work of the Church was the proclamation of the Gospel, aimed precisely towards conversion—a ministry of the Word consummated in the ministry of the sacraments. This mission required that the Church avoid equally two temptations: sectarianism and secularization. The message of the Gospel is a word of judgment upon the world, but a saving judgment. The Church exists in the world as an antinomical and heterogeneous body, in a state of opposition, but also reformation of the world. As Florovsky said in his speech at Amsterdam, August 1948:

…the real strength of the Christian position is precisely in its ‘otherness.’ For indeed, Christianity is ‘not of this world’ and is not merely one of the elements of the worldly fabric. … the strength of Christianity is rooted in its opposition to everything Christless. No secular allies would ever help the Christian cause, whatever name they bear. As Christians we have but one Heavenly Ally, Our Lord Jesus Christ, to whom all power has been given in Heaven and on earth, even in this perplexed and rebellious world of ours. For this very reason, Christians can and should never admit any other authority, even in secular affairs. Christ is the Lord and Master of history, not only of our souls. Again this gives ultimate priority to the theological issue. For our practical disagreements inevitably bring us back to the diversity of our interpretations of the Divine message and the Divine solution of our human tragedy and fall. (Florovsky, “Determinations and Distinctions: Ecumenical Aims and Doubts,” Sobornost, No. 4, Series 3, Winter 1948, 126-132, at 132)

It is dangerous to posit simple causes in the complex chain of historical events. Yet the marked wane in the cultural authority of theology and of churches themselves that became apparent only two decades or so after the Amsterdam Assembly did coincide with a certain “failure of nerve” on the part of theologians and pastors—a hesitance to address the culture at large with such robust evangel. Many preferred instead to adjust the content of their message in the attempt to be “relevant” to ever more radical forces of secularization.

Already at the meeting of the provisional committee of the WCC at Buck Hill Falls, Pennsylvania, in April 1947, Dr. J. Hutchinson Cockburn, former moderator of the Church of Scotland, had noted how “anti-Christian forces” had become so strong that the Christian tradition “no longer dominates the European scene.” “If Christ is to be enthroned over the lives of men in Europe,” he added, “it will only be by the reviving of the Church by the Grace of God and the work of the Holy Spirit. Of this revival the churches are the appointed instruments. It is Christian civilization that is at stake, not merely in Europe but also in Britain and in the United States” (“Progress Report for the World Council: Provisional Committee Holds First Meeting in United States,” Federal Church Bulletin, Vol. XXX, No. 5, May 1947, 6-7). Cockburn’s diagnosis remains even more true today. Yet it is a sad fact how many professed theologians and Christian leaders, even among the Orthodox, respond to it with sophisticated cynicism, chameleon-like compromise and defeat.

Images of Florovsky’s arrival in New York Harbor on April 7, 1947, Holy Monday—a day when many Orthodox in America celebrated the feast of the Annunciation, and all were preparing to follow after Christ to his sacred Passion in the city—show the Russian priest-theologian flanked by Cockburn and Visser’t Hooft aboard the deck of the Queen Elizabeth dressed in his riassa, cigarette visible between his fingertips, his long uncut hair blowing crazily in the wind, the expression on his face so confident as almost to radiate joy. It was precisely his spirit of confidence—confidence in the truth of Christ and his Church, and in the legacy and task of Orthodox theology—combined with magnanimity towards divided brethren, in hope of their eventual recovery, that made Florovsky’s example so singularly important for his time and context. Much depends upon the revival of that same spirit in our own.

Images of Florovsky’s arrival in New York Harbor on April 7, 1947, Holy Monday—a day when many Orthodox in America celebrated the feast of the Annunciation, and all were preparing to follow after Christ to his sacred Passion in the city—show the Russian priest-theologian flanked by Cockburn and Visser’t Hooft aboard the deck of the Queen Elizabeth dressed in his riassa, cigarette visible between his fingertips, his long uncut hair blowing crazily in the wind, the expression on his face so confident as almost to radiate joy. It was precisely his spirit of confidence—confidence in the truth of Christ and his Church, and in the legacy and task of Orthodox theology—combined with magnanimity towards divided brethren, in hope of their eventual recovery, that made Florovsky’s example so singularly important for his time and context. Much depends upon the revival of that same spirit in our own.

(In addition to the articles cited and several unpublished sources, this essay relies upon Andrew Blane, “A Sketch of the Life of Georges Florovsky,” in Georges Florovsky: Russian Intellectual—Orthodox Churchman, St. Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1993, pp. 73-91.)