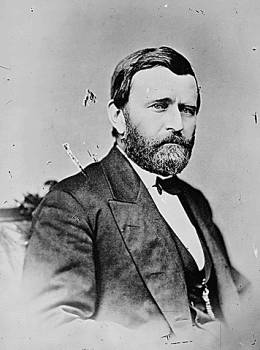

In 1869, a priest from Mount Athos paid a visit to the sitting President of the United States, Ulysses S. Grant. The Aug. 18, 1869 issues of both the North American and United States Gazette (published in Philadelphia) and the Philadelphia Inquirer ran identical blurbs:

The Rev. Father Christopher, a Greek priest from Mount Athos, has lately called upon President Grant. He is said to be a very learned man, and full of enthusiasm for his church and convent.

According to the DC correspondent in the London-based Anglo American Times (8/28/1869, page 13), the meeting between Father Christopher and Grant took place on August 13. (The Anglo American reports Father Christopher as being from Athens.) I haven’t been able to find any mention of this meeting in Grant’s papers (which are searchable on the website of the Ulysses S. Grant Presidential Library).

When I first discovered this little mystery, back in 2014, I published an article about it on another blog (the now-defunct Notes on Church History). Some of the readers started investigating for themselves, and one reader, Chad, found this lengthy description of the enigmatic Father Christopher in the Springfield Republican, Sept. 11, 1869:

There is always a distinguished stranger in Boston,–sometimes two. At present the most illustrious is Father Christophoros, a follower of St. Basil, of one of the monasteries on Mt. Athos, where he and his brother monks, to the number of five or six thousand, live a religious life and teach school for such pupils as choose to come to them. In order to support these schools, where two or three hundred poor scholars, generally Greeks, are fed and taught, the brethren send some of their number to beg in different parts of the world.

Father Christophoros is one of these pious travelers, and has lately come from a journey in Abyssinia, India and China, which he penetrated as far as Pekin. He is a handsome, bright-eyed man of middle age, with a black beard, a black gown and a black cap, looking like a rusty castor without a brim, which he wears at table and in the parlor, as well as in the street. I saw him, yesterday, turning a corner in the midst of the gale–his gown flying far in front of him, his beard streaming after it, but his cap sticking as if nailed to his head. A Protestant would have lost his hat under such stress of weather, but the good father retained his, as he has held on to so much of the old Greek language in his conversation. He speaks but little English, and no French nor German, but discourses with Dr Howe in Greek as fluently and gracefully as Hermes himself.

His monastery is on the northernmost of the three peninsulas that make out from the old Chalcidian province of Macedonia,–the same peninsula that Xerxes dug a canal through, twenty-three centuries before Gen Butler dug his equally useful one at the Dutch Gap. It is exempt from Turkish domination, and wholly under the control of the good monks, who preserve there many treasures of old manuscripts, much coveted by French and English scholars. Of these Father Christopher seems to know little, his specialty being traveling. I did not ask him how he liked Boston, but I thought it doubtful if he ever saw any worse weather off Monte Santo, than Capt Smith of the Gloucester steamboat encountered, last night, outside the harbor.

That article mentions a “Dr. Howe,” with whom Father Christopher conversed in Greek. This is Dr. Samuel Howe, founder of the Perkins Institute for the Blind and a big Hellenophile. Several years later, Howe brought to America a young Greek man named Michael Anagnos, who married Howe’s daughter and ultimately succeeded Howe as head of the Perkins Institute. Anagnos went on to play a key role in the Helen Keller story, and he was also the leader of Boston’s Greek Orthodox community at the turn of the 20th century. (For more on Anagnos, check out this article.)

Anyway, it was at this point in my original research that another reader of that 2014 article, Jeff Taylor, tracked down a Dec. 18, 1869 letter from William Cullen Bryant (editor of the New York Evening Post) to Dr. Howe. Something between Howe and Father Christopher must have gone awry. Bryant writes:

… A Monk of Mt. Athos, bearing the name of Christophorus is here asking money to be expended by his monastery in the support of in the support of orphan asylums, schools and other benevolent institutions. I am told that a note from you has appeared in the Boston papers cautioning people against him. May I ask of you a copy of it for publication here? …

The book containing the letter includes footnotes saying, “Christophorus has not been further identified,” and, “No reply from Howe has been recovered.”

And that’s it — at this point, the trail of Father Christopher runs cold. Presumably, he left the United States, either returning to Greece or continuing his world tour. Was he the real deal, or some sort of renegade or impostor? How did he get an audience with President Grant — and what did they discuss? Did he come into contact with any of the (very few) Orthodox who were living in America in 1869?

A few years after this, another enigmatic, globetrotting monk arrived on the scene: the even more intriguing Rev. A.N. Experidon, better known as “The Bulgarian Monk.” To read about him, check out these articles. And if you have any insight into President Grant’s mysterious Athonite interlocutor, drop me a note at mfnamee at gmail dot com.

Thanks for your work

Thank you for reading!