Here are links to the previous articles in this series on the global Orthodox crisis of 1917-25:

As we begin 1923, just by way of reminder: Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow was under house arrest, and while the famine in Russia was receding somewhat, people were still starving. In Syria, the French were in the process of carving up the territory of the Patriarchate of Antioch into separate countries. The British had control over the finances of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem and were working to set up a Jewish state, while the Patriarchate, in dire financial straits, was selling off property to Jewish settlers. The various Orthodox ethnic groups in America experienced internal schisms, and countless lawsuits over church property were underway. That’s just a fraction of what was going on when 1923 began, but since I’m not going to mention, say, Antioch or Jerusalem in this article, don’t forget that everything was a mess there, too.

On January 4, 1923, the Turkish delegation to the Lausanne Peace Conference formally demanded that the Ecumenical Patriarchate be removed from Turkey – preferably to Mount Athos. The other delegates proposed a compromise, whereby the Ecumenical Patriarch could remain in Constantinople but would be stripped of all political and administrative authority. Venizelos, acting as the leader of the Greek delegation, even offered to sacrifice his friend Patriarch Meletios, proposing that Meletios – an enemy of the Turks – would resign if the Patriarchate were allowed to remain in Turkey. The Turks agreed to the deal.

Then, on January 30, Greece and Turkey agreed to a “population exchange,” under which most of the Muslims in Greece would be deported to Turkey, and most of the Greeks in Turkey would be deported to Greece. Some two million people were deported, including about 1.5 million Greek Orthodox Christians living in Turkey.

In February, by now sort of a dead man walking, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios invited all of the Orthodox Churches to a meeting in Constantinople, mainly to consider revisions to the church calendar, as well as remarriage of clergy.

Also in February, an archimandrite, reportedly acting out of loyalty to the Church of Russia, assassinated the Polish primate, Metropolitan George. (I should stress, nobody accused Patriarch Tikhon or the Russian Church of being involved in the murder; the archimandrite-assassin seems to have been acting on his own.) Here’s an account of the murder, from the New York Times on February 10, 1923: “[Archimandrite] Smaragd, a former rector of the Russian Seminary at Chelm, a short time ago was suspended and sent to a small parish in Volhynia. He arrived in Warsaw yesterday and made an appointment to see the Metropolitan at 6 o’clock. After an hour’s conversation servants heard three shots, and when they rushed in found the Metropolitan dead. The monk did not resist arrest.”

In March, a delegation from the new Albanian Orthodox Church arrived in Constantinople to meet with Patriarch Meletios. It expected to receive formal recognition of Albanian autocephaly, but the Ecumenical Patriarch only acknowledged partial autonomy.

Also in March, in Russia, Vladimir Lenin suffered his third stroke and lost the ability to speak.

In April, the first Renovationist Council began in Moscow. This “Council,” which ended in early May, purported to depose Patriarch Tikhon, and it instituted a series of major church reforms, including allowing married bishops, remarriage of clergy, and marriage of monastics.

While this was taking place, on May 1, the forced “population exchange” between Greece and Turkey formally took effect. Thousands upon thousands of Orthodox Christians were forced to abandon their homelands.

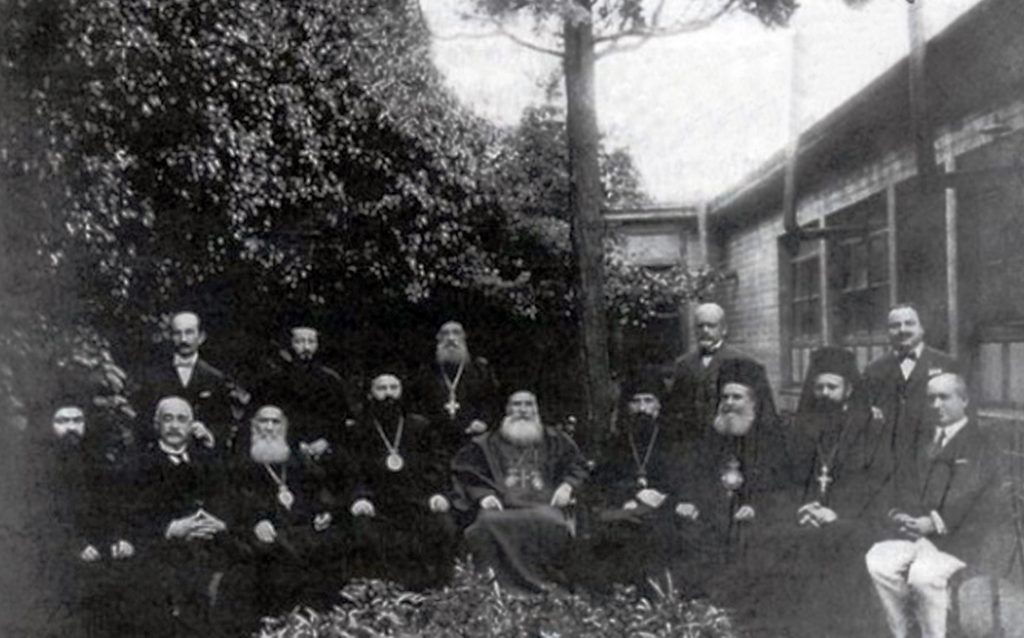

Just days after this, Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios convened the landmark “Pan-Orthodox Congress,” which ended in June with the adoption of the “Revised Julian Calendar.” On June 1, Meletios was attacked by a mob connected with the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” who dragged him down a flight of stairs, tore at his robes, and demanded that he resign. He shouted back, “Let them hang me if they will, but now I shall not retire!” An Allied police force in Constantinople intervened and saved Meletios, who very well could have been killed otherwise.

Besides the calendar, the other big topic at the Pan-Orthodox Congress was the remarriage of widowed clergy. The Congress decided to maintain the tradition of the Church in prohibiting clergy remarriage, but to allow such remarriages in exceptional cases, “making provision for the terrible position of widowed clergy at the present time,” i.e., in the wake of World War I. A final determination was referred to a future ecumenical council. The Russian Metropolitan Anastasii, future head of ROCOR, opposed the decision, arguing against what he viewed as a dangerous exercise of oikonomia.

Just after the Pan-Orthodox Congress ended, Patriarch Tikhon was set free from house arrest. He initially announced that the Russian Orthodox Church would adopt the calendar reforms of the Congress, although the Russian Orthodox people mostly rejected this, and in the end, the Russian Church retained the Old Calendar.

The next month – July – Ecumenical Patriarch Meletios separately received the Churches of Finland and Estonia – which had previously been part of the Russian Orthodox Church – under the jurisdiction of Constantinople. These would be Meletios’ final acts as Ecumenical Patriarch: within days, under pressure from the new leaders in Turkey, Meletios left the country on a British steamship bound for Mount Athos.

Also in July, the first “Arab Orthodox Congress” of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem was held in Haifa, briefly raising hopes that Jerusalem – like Antioch before it – might be able to throw off the oppressive control of the ethnically Greek Brotherhood of the Holy Sepulchre and elect a Patriarch from the native population. Unfortunately for the native Orthodox Christians, this effort ultimately stalled out.

In September, Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow issued an ukaz naming Metropolitan Platon as temporary head of the Russian Archdiocese of North America. This confirmed the previous year’s acts of the Russian Holy Synod and the All-American Sobor.

In October, the Republic of Turkey was created. On October 2, literally as the Allied evacuation of Constantinople was taking place, the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was meeting at the Phanar. Papa Efthim, leader of the “Turkish Orthodox Church,” burst into the room with a guard of Turkish police. He ordered the Holy Synod to declare Patriarch Meletios to be deposed within ten minutes. The Holy Synod complied. Then the Turkish police expelled six of the eight Holy Synod members, along with the Locum Tenens, from the building. (All of the expelled bishops had sees outside of Turkey.) Papa Efthim then replaced the seven expelled bishops with his own partisans. At that moment, it appeared that the Ecumenical Patriarchate either no longer existed, or had just been taken over by a coup d’etat.

Meanwhile, Patriarch Meletios was in Greece, and was thinking about moving the Ecumenical Patriarchate to Thessaloniki. Both the Greek government and the Church of Greece opposed this, and they finally convinced Meletios to resign as Patriarch. He signed a document backdated to September 20, after obtaining assurances from Turkey that they would open the path for a new patriarchal election, not controlled by Papa Efthim and the “Turkish Orthodox Church.” (By backdating the abdication, Meletios was attempting to undercut the actions of Papa Efthim on October 2.)

On October 6, the Turkish government issued a decree requiring any candidate for a religious election in Turkey (read: Ecumenical Patriarch) must be a Turkish citizen, and must be present in Turkey during the election process.

Also in October, the New Calendar took effect in the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

In November, the former priest John Kedrovsky, now a “bishop” of the Soviet-backed Living Church, arrived in New York and attempted to take control of St. Nicholas Russian Orthodox Cathedral. This was one of the early battles in a three-decade-long war over church properties between the Russian Metropolia (today’s OCA) and pro-Soviet religious authorities.

It was a difficult month for the Russian Orthodox abroad – the same month, a decree was issued under Patriarch Tikhon’s name, condemning ROCOR as a non-canonical body. But at the same time, another decree from the Patriarch confirmed the legitimacy of Metropolitan Evlogy’s exile jurisdiction in Western Europe. This was the beginning of the split of the Western Europe jurisdiction from ROCOR.

In Russia itself, Communist leaders held a shocking event in a Moscow opera house – an infant girl was brought by her parents to a red-draped “altar” and “christened” into Communism by Nikolai Bukharin, editor-in-chief of Pravda and a major Bolshevik figure. Four thousand people watched and cheered.

Meanwhile, in Greece on November 10, the holy hieromonk St. Arsenios the Cappadocian died, just a few months after leading his congregation from Cappadocia to Corfu as part of the forced population exchange between Greece and Turkey. One of his parishioners was an infant who grew up to be St. Paisios the Athonite, one of the greatest saints of our time.

Also in November, Pope Pius XI issued a papal encyclical, calling on the Orthodox Churches to submit to the authority of the Pope.

In December, the Holy Synod of Constantinople elected Gregory VII as Patriarch. Papa Efthim and his supporters again mobbed the Phanar and took control of the building. But this time, the Turks weren’t on his side – Turkish authorities expelled Papa Efthim and declared their acceptance of the election of Patriarch Gregory.

In April (1922), the legitimate Russian Holy Synod appointed Metropolitan Platon Rozhdestvensky as the temporary head of North American Archdiocese.

In September (1923), Patriarch Tikhon of Moscow issued an ukaz naming Metropolitan Platon as permanent head of the Russian Archdiocese of North America.