Working on the history of Orthodox Christianity in North America means toiling in a vineyard mostly unplanted. Unlike other significant denominations on this continent, scholars of American religions have paid very little attention to Orthodoxy. As a result, there’s a lot of work to be done, and thankfully, a growing number of people are finally doing it. This essay is more a reflection than anything. A musing on the state of the field.

Working on the history of Orthodox Christianity in North America means toiling in a vineyard mostly unplanted. Unlike other significant denominations on this continent, scholars of American religions have paid very little attention to Orthodoxy. As a result, there’s a lot of work to be done, and thankfully, a growing number of people are finally doing it. This essay is more a reflection than anything. A musing on the state of the field.

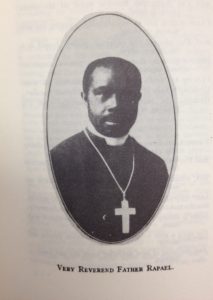

Some of the most significant work that SOCHA has supported and published over the years has dealt with figures who represented “firsts” of one form or another. A lion’s share of such research has dealt with Fr. Raphael Morgan, acknowledged as the first priest of African descent to minister in the Americas. As Matthew Namee noted in an article here on OH.org a few days ago, Morgan’s fascinating story was recognized by a smattering of scholars decades ago. Yet it was only when Matthew and Fr. Oliver Herbel began researching Morgan in the mid-2000s that most anyone became aware of his existence.

In a recent post on Public Orthodoxy, the blog of the Fordham Orthodox Christian Studies Center, Fr. Oliver returned to Morgan’s story. (In the interest of full disclosure: I have written for Public Orthodoxy, and was the OCSC’s first dissertation completion fellow during the 2017-18 academic year.) In recent months, several researchers, namely Fr. Samuel Davis and Fr. John Perich, have uncovered new details about Morgan’s life. Most significantly, they have confirmed details of his death, and found his unmarked burial site. This is great sleuthing that deserves to be highlighted, a wonderful example the archival digging historians love.

This recent uptick in attention has led some involved in the telling of Morgan’s story to suggest his place as the first priest of African descent in America merits his glorification as an Orthodox saint. This is something that seems endemic to individuals associated with historic “firsts,” such as St. Herman of Alaska and St. Alexis of Wilkes-Barre. This is a point around which I intend to tread carefully. First, I am not a communing Eastern Orthodox Christian, and I do not orient my work towards any kind of constructive purpose for the life of the church–though I certainly welcome readers to receive it as such. I would also add that there are unintended consequences for the historian to delve into the lived religious experiences and devotions of faithful people. Longtime Orthodox History readers may recall a lively and intense debate nearly a decade ago, now (partially) scrubbed from the internet, which challenged hagiography regarding the martyrdom of Peter the Aleut (Cungagnaq) in nineteenth-century California, and included one bold assertion that Peter never actually existed. A number of spirited, sometimes painfully raw discussions ensued that touched on issues of historical memory, race, and colonial empire. Plainly, delving into judgments on sanctity is not always the best idea if you’re a working historian or scholar of religion.

Now that door has been opened regarding Fr. Raphael Morgan. Responding to calls for Morgan’s glorification, Matthew published nearly fifty pages of archival documents pertaining to Morgan’s divorce. They include Charlotte Morgan’s harrowing accounts of physical and emotional abuse inflicted by her husband across much of their turbulent marriage. Some details were verified by a witness. Fr. Raphael did not appear in court to refute the allegations. Certainly these accounts are extremely troubling and must be taken seriously. We are obliged to believe Charlotte Morgan, including (and especially) those invested in Morgan’s potential glorification. But as concerning as this aspect of Fr. Raphael’s life is, I wonder if the question of sanctity is even the most compelling way to frame Morgan’s place in Orthodox history on this continent.

For me, the question is historiographic: Is Fr. Raphael Morgan really all that important in the historical narrative of Orthodoxy in North America? In other words, is being the first priest of African descent meaningful in its own right when you situate his life within the bigger picture? I wonder about this in terms of my own questions about the agency of historical work. Is the point of studying Orthodoxy in the Americas to identify possible candidates for glorification and weave constructive hagiographies? Or is it to move beyond individual stories (especially those of clergy) to find broader meaning in the Orthodox experience on this continent?

It seems to me that there is a need for our field to make key differentiations in the kinds of stories we tell. There are critical differences between compelling stories, noteworthy trivia, and events and figures with sustaining historical significance. As Matthew pointed out, Morgan’s story certainly reflects a compelling story. But is the full breadth of his biography historically significant from an Orthodox perspective? I’m not so sure.

Fr. Patrick Mythen, 1920 (Springfield Republican)

Allow me to frame this in terms of a story long asserted to involve Morgan. With Matthew’s generous collaboration, I spent several years studying the life of Fr. Patrick Mythen and his involvement in the establishment of an English-speaking Orthodox parish in New York during the spring and summer of 1920. This American Orthodox Catholic Church of the Transfiguration was the first exclusively English parish in the Americas. Indeed, Mythen’s story is compelling. An inveterate religious searcher, Mythen intertwined his work in the Irish self-determination movement with his brief time as an Orthodox priest. Like Morgan, Mythen passed from the Episcopal Church into the world of the episcopi vagantes through the notorious Old Catholic Archbishop Joseph René Vilatte. Mythen converted to Orthodoxy in April 1920, alongside several other clergymen, to work in the Russian Archdiocese’s English-Speaking Department. Established in 1905, though mostly dormant by the time of Mythen’s conversion, the English Department adopted the altruistic goal of building an Orthodox Church reflective of the full diversity found in the Americas.

Part of this work involved evangelization to African-Americans. Among the clergy who entered Orthodoxy with Mythen was an Old Catholic monk of African (possibly Afro-Caribbean) descent, Fr. Antony (Robert F.) Hill. With Hill, Mythen was intimately involved in the formation of what would become known as the African Orthodox Church (AOC). From the first historical treatments of Fr. Raphael Morgan, however, scholars have connected a cluster of disparate dots to grant significant credit to Morgan for the AOC’s establishment. They point to overlaps in the careers of Morgan and the AOC’s founding bishop, George Alexander McGuire, when both men served Black missionaries for the Protestant Episcopal Church. They posit that Morgan was influential in steering McGuire towards Orthodoxy. This version of the story involves a lot of crossed paths and possible associations, and is woven from a paucity of archival proof that historians acknowledge invites significant conjecture.

There’s a reason for this. The AOC was a product of McGuire’s desire to transform Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA) into a religious denomination, a move which Garvey himself rejected. Going it alone, McGuire formed his own church, infusing high-church Episcopalianism with Garveyite rhetoric of pan-Africanism and Black liberation. Yet as a 1916 letter against Garvey indicates, Morgan was decidedly ambivalent about these very same ideas. Unless Morgan had a significant change of heart about Garvey between 1916 and 1921, his involvement in the formation of the AOC, even with the most generous assumptions about his acquaintance with McGuire, seems improbable.

My research into the AOC, not surprisingly, revealed nothing about Morgan. Rather, it was Mythen and Hill, working under the auspices of the Russian Archdiocese, who were most invested in McGuire’s fledgling church. For Hill, this was a matter of his own people’s self-determination. For Mythen, a somewhat prominent figure in the Irish freedom movement in the United States, it was an extension of long standing links between Garvey and American Irish organizations. Mythen and Hill both attended a UNIA convention and early sessions of the AOC’s General Synod in August 1921, showing support for what they hoped would become a vicariate within the Russian Archdiocese to evangelize to African-Americans. In the coming months, Mythen facilitated negotiations between McGuire and Orthodox hierarchs. The Russian Archdiocese briefly loaned Hill to McGuire to help the AOC get on its feet, leading to Hill’s departure from the Orthodox Church to become a priest (seemingly briefly) under McGuire.

These links between McGuire’s AOC and the Russian Archdiocese were short-lived, and unsuccessful, spanning only a brief period in late 1921. McGuire elected to maintain his church’s ecclesiastical independence, as he was reluctant to place the AOC in a predominantly white denomination. His church would retain the term “Orthodox,” even though the AOC never adopted Orthodox theology or liturgical practices in any way. Instead, it retained trappings of high-church Episcopalian worship and its distinctive Garveyite teachings. Ultimately, the English Department’s negotiations with McGuire marked one of few high points in a nearly two-decade history. Its English-speaking parish lasted only a matter of months during the summer of 1920. In 1924, the flagging department folded. By June of that year, neither Mythen, nor any of the other convert priests who entered the church with him four years earlier, remained Orthodox Christians.

Like Morgan, excavating the English Department’s story required deep archival mining for what usually amounted to little more than small tidbits of historical information. These isolated data points collectively gestured towards a compelling story, but one without a great deal of lasting historical significance for the Orthodox Church. Plainly, it didn’t really connect to much of anything. By mid-century, when English-speaking Orthodox parishes were being established in significant numbers, it seems no one remembered that the English Department had tried the same thing in New York in the 1920s. I am left to conclude that until my colleagues and I began our research into the English Department, virtually no one had given much thought to Fr. Patrick and the English Department for well over half a century. When I sojourned to Queens to find Fr. Patrick’s grave in 2013, I found an empty patch of grass.

Grave of Fr. Patrick Mythen, Calvary Cemetery, Queens, NY

Similarly, not until Matthew and Fr. Oliver re-excavated Morgan in the mid-2000s did most anyone think about the first African-descended priest in North America. We now know Morgan died in 1922, but virtually nothing is known about Morgan after 1916. That said, there isn’t much of a paper trail before then, either. The paucity of archival data is not concerning in itself, especially in the study of African-American religion, but it raises an eyebrow here. If Morgan indeed lived in Philadelphia for the bulk of his ministry, he was at the epicenter of one of the most active Orthodox regions in North America. Whether it was for personal reasons, or even issues of racism within Orthodox communities of the time, it does not seem that there was much, if any interaction between Morgan and the Orthodox world around him. He did not influence the formation of the, the AOC, the first great push to bring other African-Americans to Orthodoxy, even as his path overlapped those who actually did. He never had a parish, nor much of a congregation. His death apparently went unnoticed. As recent discoveries about his demise confirm that like Mythen, Morgan was buried in an unmarked grave.

So what I find myself coming back to is my feeling after lengthy efforts to tell Fr. Patrick’s story, and a sense I get from what I’ve read over the years as researchers have uncovered piecemeal the life of Fr. Raphael. These stories can, and should be told, but cannot be given more significance than the historical record allows. Morgan was the first person of African descent to serve as a priest in North America. But his rather self-contained story, seemingly disconnected in most every way from the life of the Orthodox Church in North America during his lifetime, doesn’t tell us more than that. As historians, we can recognize his unusual decision to become an Orthodox priest, while still acknowledging his importance may lay in that simple fact alone. And in light of revelations about his private life, we should be telling his story with far more objectivity, and nuance.

Perhaps Morgan’s historical significance might come in the African-Americans who have discovered, and been edified by his very historical existence, including at least one of the researchers who is contributing to new research into his story. As Fr. Oliver gestured towards in his article, this is an important element to highlight at a time when self-identified Orthodox Christians have assumed prominent positions on the American alt-right. Morgan’s example reminds us, crucially, that the Orthodox Church’s reach on this continent has long encompassed a rich diversity of believers, including African-Americans. There is, however, yet another interpretation, one which questions the connection of the forest to the trees. What if St. Herman’s reach never surpassed Spruce Island? What if St. Alexis’ parish in Minneapolis had not inspired scores of others to similarly convert to Orthodoxy en masse? While “firsts” matter, their importance might be found only in the extent to which they influenced a second.