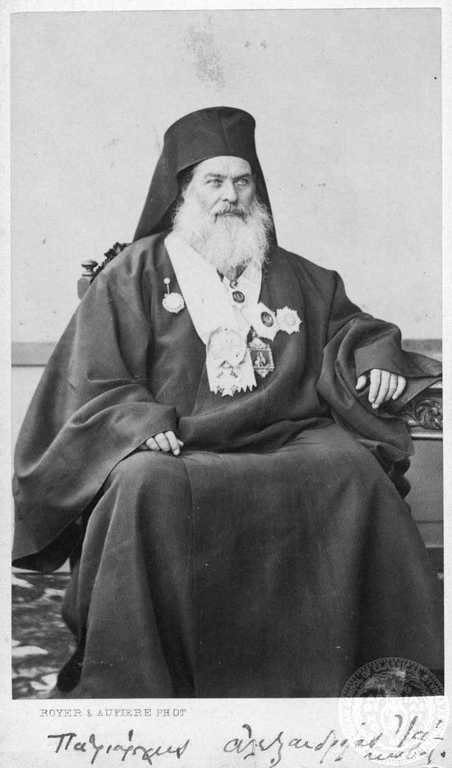

Patriarch Iakovos of Alexandria was chosen by the Patriarchs of Constantinople, Antioch, and Jerusalem in 1861.

The Patriarchate of Alexandria was founded by the Apostle Mark, at a time when Alexandria was essentially the second city of the Roman Empire, after Rome itself. Largely because of this, in the earliest centuries of church history, the Church of Alexandria was second only to Rome in preeminence among the churches, a notch ahead of Antioch. After the rise of Constantinople and the reestablishment of Jerusalem in the fifth century, Alexandria had a secure place as one of the Pentarchy — the five churches that held a special place of leadership in the global Orthodox Church.

In the centuries that followed, Alexandria technically retained its place in the Pentarchy, but in practice it fell into deep decline. The fifth century Monophysite heresy split the Alexandrian Church, and the seventh century Arab conquest of Egypt reduced the Patriarchate to a shell of its former self. Metropolitan Makarios Tillyrides of Kenya refers to the Arab period as “one prolonged torment for Christians of Egypt.” During this era, the Orthodox population of the Patriarchate fell from 300,000 to 100,000. Many Patriarchs of Alexandria moved to Constantinople, living there permanently. Metropolitan Makarios writes, “It was not unknown for the election of the Patriarch to take place there.”

In 1517, the Ottoman Empire conquered Egypt, and this event offered a new lease on life for the Patriarchate, as the Ottoman Sultan promised to safeguard Alexandria’s rights and privileges. The Ottomans opened up Egypt to trade with the West, leading to contacts between Alexandria and the European powers and their churches. Representatives from the Patriarchate, including the Patriarch himself, began fundraising tours in the West by at least the mid-17th century, and the Patriarchate became a focal point for rivalry between Roman Catholic and Anglican/Protestant missionaries. While not as glorious as it was before the Arab conquest, the Patriarchate was once again in a position of influence and relevance in the broader Orthodox world. Land donations in places like Wallachia and Moldavia gave the Patriarchate newfound financial stability. Having said all this, the actual Orthodox flock of Alexandria was tiny: a small community that spoke Arabic, ruled over by immigrant Greek-speaking bishops.

This brings us to the 19th century, which Metropolitan Makarios says “could most aptly be described as the period in which the Patriarchate of Alexandria experienced a renaissance.” And in one sense it was: the ruler of Egypt, Muhammad Ali, was technically an Ottoman vassal, but in practice he was an all-powerful autocrat who ruled a de facto independent Egypt as he saw fit from 1805 to 1848. Ali encouraged large-scale Greek immigration to Egypt, leading to the growth of the Patriarchate and its re-establishment as a fully functional church. At the same time, the 19th century also witnessed numerous instances in which Alexandria’s status as an autocephalous church was, if not officially rejected, at least practically ignored.

***

Throughout the 19th century, the Patriarchate of Alexandria was basically a single diocese with one ruling hierarch (the Patriarch) and a handful of titular bishops. In 1818, Patriarch Theophilos II became ill and went to his native island of Patmos to recuperate. While there, he was initiated into the Filiki Eteria, the Greek revolutionary secret society. Once the Greek Revolution began, Theophilos again traveled to Patmos to lead the revolution. He never returned to his see in Egypt. In October 1825, Theophilos was deposed by a synod convened by Ecumenical Patriarch Chrysanthus, under pressure from the Ottoman government, with the rationale being that he had abandoned his see. He was succeeded by Patriarch Hierotheos.

In 1845, Patriarch Hierotheos died, and the Holy Synod of the Ecumenical Patriarchate held an election to choose his successor. They elected one of their members, Artemios of Kyustendil — a direct violation of Alexandrian autocephaly. The faithful of Alexandria and the Egyptian government rejected Artemios, and the Ottoman government gave in to the pressure and refused to confirm him. The Russian embassy — a reliable defender of the Phanar during this era — protested that the Ottomans had violated the authority of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The dispute dragged into 1847, when, finally, the Egyptian government arranged for a local election in Egypt, and the return of the patriarchal residence from Constantinople to Alexandria.

During this period, under the autocratic Egyptian governor Muhammad Ali, many Greeks had begun to immigrate to Egypt, reinvigorating the Patriarchate. Even so, an 1857 population estimate published in the West reported just 5,000 Greek Orthodox in the country — probably an outdated number, but regardless, an indication of just how tiny the Patriarchate of Alexandria was, not so long ago.

In 1861, Patriarch Kallinikos of Alexandria resigned after just three years on the patriarchal throne. His tenure was notable for his efforts toward reconciliation with the Coptic Church. After Kallinikos resigned, the Orthodox communities in Cairo and Alexandria could not agree on a successor – each had their own favored candidate. They submitted the dispute to the Ecumenical Patriarch, who, along with the other two Greek Patriarchs (Antioch and Jerusalem), chose a different man, Iakovos, as Patriarch.

Patriarch Iakovos died unexpectedly at the end of 1865. His successor, Nikanor, established a four-man Holy Synod to assist the Patriarch. This was the first Holy Synod of Alexandria in the modern era. But Nikanor was already rather old, and in 1869, he announced his decision to retire. The Church of Alexandria was divided between two candidates to succeed him: one party favored an aged monk named Eugenios, the other an Archimandrite Neilos, from Mount Athos. In March 1869, Nikanor resigned in favor of Neilos, who was initially elected Bishop of Pentapolis and then Patriarch. The pro-Eugenios party refused to accept the results, and the rival factions physically fought each other in the streets of Cairo. Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory stepped in, ordering Neilos, as a monk of Mount Athos (and thus under Constantinople’s jurisdiction) not to take office as Patriarch of Alexandria. Neilos, with support from Antioch and Jerusalem, refused to step aside, so the Ecumenical Patriarch anathematized him.

The succession crisis continued into 1870. In February, the Ottoman government in Egypt tried to get the clergy and laity of the Patriarchate to hold a local election, but this failed, since the factions could not agree on a candidate. Finally, the Egyptian government referred the problem to the Ottoman central government in Constantinople, which in turn directed the Ecumenical Patriarchate to choose a new Patriarch of Alexandria. In May, former Ecumenical Patriarch Sophronius III, who had been deposed in 1866, was elected Patriarch of Alexandria by the Holy Synod of Constantinople. In announcing the election of Sophronius, Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory was careful in his wording, not mentioning the Egyptian or Ottoman governments or even the ousted Patriarch-elect Neilos. Instead, Gregory stated that the Orthodox of Alexandria had asked him to make a choice for them, and he chose Sophronius.

In 1882, the British took control of Egypt, putting a greater arm’s length between the Patriarchate of Alexandria and the institutions of the Ottoman Empire. But by 1889, the hierarchy of Alexandria had dwindled to just a single bishop – Patriarch Sophronius IV himself – and so he arranged for the young St Nektarios to become a titular bishop, in line to be the next patriarch. Due to evil intrigue, St Nektarios was eventually banished, and Patriarch Sophronius died in 1899. The locum tenens drew up new patriarchal election rules, providing for extensive lay participation and hedging against outside involvement. The lay delegates elected Metropolitan Photios of Nazareth as the next patriarch, although for years, the Ecumenical Patriarchate refused to recognize him and did not commemorate him in the diptychs. Since Photios was already a consecrated bishop, there was no need to hold a consecration. Photios spent decades on the Alexandrian throne, and he worked to secure his Patriarchate’s independence, expanding its hierarchy to eliminate any future need to appeal to Constantinople for assistance. It was under Photios that Alexandrian dioceses were established outside of Egypt, and Photios’s successor — the larger-than-life Meletius Metaxakis — received the first native sub-Saharan African converts, which led Alexandria to add to its title the words “All Africa.”

Patriarch Photios expanded the hierarchy of Alexandria and secured its independence from outside control.

***

Fr John Erickson recently defined “autocephaly” in this way: “In present-day usage, a church is termed autocephalous if it possesses (1) the right to resolve all internal problems on its own authority, independently of all other churches, and (2) the right to appoint its own bishops, among them the primate or head of the church, without obligatory expression of dependence on another church.” It’s pretty questionable whether Alexandria satisifed either of those very basic criteria in the 19th century. On multiple occasions, its Patriarch was appointed by outside church authorities — either Constantinople by itself or along with Antioch and Jerusalem. Its internal disputes could not be resolved internally. Its episcopate was tiny, far too small to depose a bishop, as evidenced by the 1825 deposition of the Alexandrian Patriarch by the Holy Synod of Constantinople. Yet despite all of this, no one questioned Alexandria’s continued status as a Patriarchate and a member of the ancient Pentarchy, second in the diptychs after the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

The long era of Patriarch Photios really represents a sort of re-establishment of Alexandrian autocephaly. Today, Alexandria has about 35 bishops and a continent-sized territory, with a flock that’s growing thanks to extensive missionary efforts. Yet even today, Alexandria continues to receive its Holy Chrism from Constantinople, retaining a degree of dependence that hearkens back to a past era of Alexandrian weakness. Like the Church of Cyprus, the story of Alexandrian autocephaly in the modern era is complex, not lending itself to the binary you-have-it-or-you-don’t idea of autocephaly.

Main Sources

I am indebted to my friends and colleagues Nicholas Chapman and Sam Noble for their very helpful insights and suggestions regarding the Patriarchate of Alexandria from the 16th-19th centuries.

Anton Bertram, Report of the Commission appointed by the Government of Palestine to inquire into the affairs of the orthodox patriarchate of Jerusalem (Oxford University Press, 1921).

Karl Beth, Die orientalische Christenheit der Mittelmeerländer: Reistudien zur Statistik und Symbolik der griechischen, armenischen und koptischen Kirche (C.A. Schwetschke und sohn, 1902).

Fr John H. Erickson, “Autocephaly and Autonomy,” St Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 60:1-2 (2016), 91-110.

Jack Fairey, The Great Powers and Orthodox Christendom: The Crisis over the Eastern Church in the Era of the Crimean War (Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

P.M.K. Strongylis, Saint Nectarios of Pentapolis’ life and works: a historical-critical study (Durham theses, Durham University, 1994).

Metropolitan Makarios Tillyrides of Kenya, “The Patriarchate of Alexandria Down the Centuries.”

Matthew, thank you for this post. As a descendant of Alexandrians, I enjoyed it. I completely agree with your concluding sentence, but I think your title is somewhat misleading as you say yourself the church’s place in the pentarchy was “not officially rejected.” Also, I am not sure that St. Nectarios was the only hierarch of the Alexandrian throne, which appears to be part of your analysis on the autocephaly of the patriarchate. St. Nectarios replaced a bishop as Metropolitan of the Pentapolis. I also believe it was other hierarchs who conspired against him, but could be wrong. Finally, I would contend that canonical irregularity was the norm in the late byzantine and ottoman period–take a look at Vryonis’ “Decline of Hellenism in Asia Minor” and Runciman’s “The great church in captivity.” Set against this background, it is hard to credit the definition of “autocephaly” you provide, and agree with your comment that autocephaly in this period is non-binary. To that end, would the Russian church be considered to have lost its autocephaly post-Peter I since the procurator effectively made decisions and there was not truly a primate? I think it would hard for that argument to hold water, just as I think it is hard for the argument that the Alexandrian church “lost” autocephaly. In any case, thank you as always for your thoughts and research, always very fascinating!

Regarding the statement that, prior to the consecration of St Nektarios, the episcopate of Alexandria had dwindled to just one bishop (the Patriarch): My source is P.M.K. Strongylis, Saint Nectarios of Pentapolis’ life and works: a historical-critical study (Durham theses, Durham University, 1994), pages 64-65. Strongylis says, “As the Patriarchate of Alexandria had no Prelates at that time, because of the death of Alexandria’s Patriarchal Warden, the Metropolitan Matthaios Vallinakes of Thevais, and the dismissal from the Throne of Patriarchal Warden of Cairo, the Metropolitan Ignatius of Libya, the aforementioned election and ordination of Saint Nectarios and the new Metropolitan Germanos Vourlalides of Thevais was made by Patriarch Sophronios and two Prelates provisionally residing there at that time, the Archbishop of Sinai Porphyrios I and the Archbishop Antonios Hariatis of Corfu.”

The so-called “larger than life” Patriarch Meletios Metataxis was a Mason and an agent of foreign powers (such as England and France), who arranged for him to be first the Patriarch of Constantinople and THEN the Patriarch of Alexandria, causing division in Orthodoxy in many ways. He should receive no credit at all for “receiving” the first sub-Sahara converts, since they found Orthodoxy on their own after leaving the colonial Anglican church, only to be told by meletios to stay in the Anglican church since “Orthodoxy and the Anglican church were going to merge fairly soon”, so why bother joining Orthodoxy?