Today I’m going to try to tell the story of how the Romanian Orthodox Churches became independent. You’ll notice that I said “Churches,” not “Church” – that’s because, in the 19th century, there were no fewer than three distinct, independent Romanian Orthodox Churches:

- The “Danubian Principalities” of Wallachia (aka Muntenia, in the south of modern Romania, including Bucharest) and Moldavia (easternt)

- Transylvania (central Romania)

- Bukovina (northern Romania)

During the first half of the 19th century, all of these churches were under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. There were other Romanian regions in addition to these – for example, Bessarabia, in the east, was annexed by the Russian Empire in 1812. Wallachia and Moldavia, which are kind of the core historic regions of Romania, were part of the Ottoman Empire and were ruled over by ethnically Greek princes known as “Phanariots.” The earliest stages of the Greek Revolution were launched from these regions, with support from the local Phanariot princes. The Ottoman government responded by replacing the Phanariots with new rulers, more loyal to the Sultan. This was really the beginning of the breakaway of the Orthodox Churches of the Danubian Principalities from the Ecumenical Patriarchate.

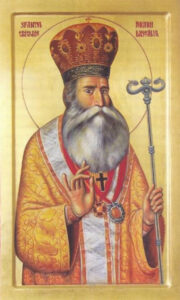

In 1823, the new Prince Grigorie IV Ghica of Wallachia called a local council of twenty-three churchmen to elect a new Metropolitan. The council chose a native Romanian hierodeacon named Grigorie, who had been born in Bucharest and was tonsured a monk at Neamț monastery by the great St Paisius Velichkovsky in 1790. Grigorie then spent time on Mount Athos before returning to Romania. Although it had been traditional for either the Bishop of Râmnic or the Bishop of Buzău to become the next Metropolitan, Grigorie’s election broke from this practice, as he was only a hierodeacon. During his tenure as Metropolitan, Grigorie appointed new bishops, established new churches, schools, and seminaries, and published a 12-volume collection of the lives of the saints. He was particularly beloved for his care for the poor, widows, and children, and in 2006, he was canonized as St Grigorie the Teacher.

Two months after the enthronement of St Grigorie, the Prince of Wallachia ordered that all Greek monastery abbots be replaced by local Romanians. This ended the flow of funding from the Danubian monasteries to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which understandably led to protests by the Patriarchate.

Five years later, during the Russo-Turkish War in 1828, the Russian army occupied the Danubian Principalities. When the war ended the following year, the peace treaty recognized nominal Ottoman rule over the Principalities, but it also allowed for continued Russian occupation. For all intents and purposes, the Principalities were no longer under the control of the Ottoman Empire. Independence from the Ottomans didn’t necessarily mean better conditions for the church. St Grigorie was exiled from 1829 to 1833, but he retained his see and ultimately returned to Bucharest, where he died during a vigil service in 1834. After St Grigorie’s death, the Wallachian Church was without a leader for six years, until Metropolitan Neofit was elected in 1840. He had to navigate an ambiguous situation – was he under the Ottomans, or the Russians, or a local government? – and upon his election, he made sure to inform the Tsar of his new position.

In the sister Principality of Moldavia, Metropolitan Veniamin led the church for some four decades, from 1803 to 1842 (minus a couple of interruptions). In his later years, Veniamin clashed with the ruling Prince of Moldavia, and in early 1842, the Metropolitan resigned in protest. The prince then attempted to impose his own leader on the Moldavian Church, without the consent of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Ecumenical Patriarch stepped in – he agreed to accept Veniamin’s resignation but rejected the prince’s chosen successor. The prince went along with this, and the Moldavian Church had an election to choose its next Metropolitan, who was confirmed by the Ecumenical Patriarch. Meanwhile, Russian clergy in Moldavia tried but failed to rally the people to petition for the Moldavian Church to break away from Constantinople. In the years to come, the Moldavian Church suffered from repeated battles over the primatial throne, with various bishops and state actors vying for power. The Russian Empire was involved in both of the Danubian Principalities for twenty-seven years, until the end of the Crimean War, when Russia was forced to withdraw from the territories.

***

Following the Russian withdrawal, in 1859, Prince Alexandru Ioan Cuza was elected prince of both Moldavia and Wallachia, uniting the two principalities under a single ruler. Three years later, the principalities formally adopted the name “Romania.” Cuza quickly began to assert his authority over the Orthodox Church in the Danubian Principalities, which at this point had no unified governing structure – no primate, no Holy Synod, and a relatively nominal canonical dependence on the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In June 1859, Cuza appointed a new bishop for the see of Buzau, against the wishes of Metropolitan Nifon of Wallachia. Cuza and his government began confiscating monastic properties. In September, Metropolitan Sofronie of Moldova wrote to Cuza protesting the government’s arbitrary actions. The Prince responded by threatening to depose the Metropolitan.

The following spring, Metropolitan Sofronie protested to the Romanian National Assembly. Prince Cuza retaliated harshly: he dissolved thirty-three Moldovan monasteries and then imposed heavy taxes on the remaining monasteries in Sofronie’s territory. In February 1861, the government organized a synod of twelve bishops, which removed Sofronie from his see. The embattled metropolitan died a few months later.

This was only the beginning. In 1863, Cuza ordered the mass confiscation of all monastic estates throughout the Danubian Principalities. He decreed, “All monastic assets of Romania are and remain the property of the State.” As a result of this law, 26% of all land in the Romanian principalities passed into government control. Most Romanian monasteries were, at this point, controlled by Greek-speaking clergy, and the Ecumenical Patriarchate strongly opposed the seizure of these monastic lands. The following year the Romanian government offered to pay the Patriarchate an indemnity, which the Greek hierarchy rejected. The law also severely limited the ability of men and women to take up the monastic life: with the exception of older people (men aged at least 60, women 50), only those with formal theological training could become monastics. Separately, Cuza also mandated the use of the Romanian language throughout his dominions. Part of the fallout from Cuza’s reforms was the deposition of Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim II, who was harshly criticized for his poor handling of the crisis.

Prince Cuza’s takeover of the Orthodox Church in Romania continued in 1864. In December of that year, he issued a law, “Organic Decree for the Establishment of a Central Synodal Authority,” declaring the Romanian Orthodox Church to be autocephalous and creating a unified Holy Synod for the principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia. The law stipulated, “The Romanian Orthodox Church is and remains independent of any foreign ecclesiastical authority in matters of organization and discipline.” This was opposed by the Ecumenical Patriarch, but Cuza countered that autocephaly wasn’t such a revolutionary step, as Romania had always been autonomous. Cuza said that Constantinople “never made laws for the Romanian Church, but only gave a blessing to choices of hierarchs made in the country.”

Then in January 1865, Metropolitan Nifon of Ungro-Wallachia received the title “Metropolitan Primate” of Romania. In May, the Romanian government decreed that all bishops of the Romanian Church were to be appointed by the Prince, a stark break from the tradition of canonical election. In the spring and summer of 1865, the Ecumenical Patriarch and the Romanian hierarchy exchanged letters regarding Romania’s autocephaly, with Patriarch Sophronius claiming that Romanian autocephaly was uncanonical and the Romanian metropolitans asserting that the Romanian Church had always been autonomous and never truly subject to Constantinople.

Prince Cuza’s actions, culminating in a declaration of autocephaly for the Romanian Orthodox Church (i.e., the Orthodox Church of the Danubian Principalities) was strikingly similar to the actions of King Otho and his government in Greece a couple decades earlier. In both cases, the new government declared the local church free from outside (i.e., Ecumenical Patriarchate) control, while simultaneously imposing a high degree of state authority and control over the church, seizing church property and placing restrictions on the monastic life. In a way, autocephaly for Romania – like Greece before it – amounted to trading out one overlord for another.

***

While this was happening in the Danubian Principalities (now known as “Romania”), another group of Romanian Orthodox were also asserting their independence. Back in 1848, in the city of Sremski Karlovci in what was then Hungary, the local Serbian Orthodox people established the Patriarchate of Karlovci, which would have jurisdiction over all Orthodox Christians in Hungary (which was then part of the Habsburg Empire). The Orthodox community in Hungary wasn’t monoethnic – although the new patriarchate was controlled by Serbs, the church included a lot of Romanians, particularly in the region of Transylvania. In 1862, a coalition of Romanian Orthodox leaders in Hungary petitioned Austro-Hungarian Emperor Franz Joseph, asking for a Romanian Orthodox jurisdiction to be broken off from the Patriarchate of Karlovci. The signatories included two leading bishops, Metropolitan Prokopije Ivanovic of Arad and Metropolitan Andrei Șaguna of Sibiu.

In December 1864 – the same month that Prince Cuza declared the Romanian Church in his domains to be autocephalous – over in Transylvania, the Romanian Diocese of Sibiu, led by Metropolitan Andrei Saguna, declared itself to be independent of the Patriarchate of Karlovci. This re-established the Metropolitanate of Transylvania, which had been suppressed way back in 1701.

***

Back in the Danubian Principalities / Romania, in February 1866, Prince Cuza was forced to abdicate. In April, he was succeeded by the German Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, who took the name Carol of Romania. At this point, it was by no means guaranteed that the two principalities of Wallachia and Moldavia, united only a few years earlier by the dual crowning of Prince Cuza, would remain unified under Carol. Many in Moldavia opposed the union with Wallachia. In April, on St Thomas Sunday, Metropolitan Calinic of Moldavia (not to be confused with his contemporary St Calinic of Cernica) gave an impassioned anti-unification speech in the Moldavian capital of Iași. Anti-unionist protesters rioted, and the uprising was put down by two infantry battalions. Metropolitan Calinic himself was arrested and imprisoned in a monastery, and for a time he was suspended from the episcopate. In an effort to mend fences, Prince Carol pardoned him the next month.

In June, the Romanian Parliament adopted a new constitution, which included an article asserting the complete independence of the Romanian Church, which was to be governed by a “central synodal authority.” In October, Prince Carol visited Constantinople and met with the Ecumenical Patriarch, leading to some hope for a thaw in relations between the Church of Romania and the Ecumenical Patriarchate. In 1869, the Romanian senate adopted a new Organic Law for the Church, and Prince Carol, again trying to appease the Ecumenical Patriarchate, decided to send the new law to Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory VI for approval. Gregory, in the midst of his own battle over the proposed breakaway of the Bulgarian Church from Constantinople, had other ideas. Far from accepting Romanian church independence, Patriarch Gregory demanded that all bishops (not merely the primates) of the Church of Romania be confirmed by the Ecumenical Patriarchate, that the Ecumenical Patriarch’s name be commemorated liturgically, and that Constantinople supply Holy Chrism to Romania. The Romanians rejected Gregory’s demands, although Prince Carol did agree that Romania would receive its Holy Chrism from the Patriarchate.

Up to this point, the Orthodox Churches of the two principalities – the Metropolis of Wallachia and the Metropolis of Moldavia – were still technically separate ecclesial entities. In 1872, they formally merged to create the Romanian Orthodox Church. In December, the Romanian government issued the “Organic Law for the election of Metropolitans and Eparchial Bishops and the creation of the Holy Synod of the Holy Autocephalous Orthodox Romanian Church and of the upper ecclesiastical consistory.” The law had been in the drafting process for the past six years. Somewhat moving away from Prince Cuza’s controversial law under which bishops were appointed by the Prince, the 1872 Organic Law provided for bishops to be elected by an electoral college consisting of bishops, senior archpriests, and all of the state legislators who were Orthodox. This continued intrusion of the state into the affairs of the church was a source of frustration for the Romanian hierarchy.

***

Back in Transylvania, on June 15/28, 1873, the powerful Romanian Metropolitan Andrei Șaguna of Sibiu, who had reestablished the independence of the Church of Transylvania, died at the age of 74. His last words, directed toward his vicar bishop, were, “I’m ready, Nicolae! God’s will be done, everything is in order. Peace be with you all, do not quarrel!” In his will, he insisted upon a simple funeral: “My funeral shall be done before noon, without pomp, music and sermon […] my confessor alone shall celebrate the Holy Liturgy and accomplish the funeral service.” In 2011, the Romanian Orthodox Church glorified Metropolitan Andrei as a saint.Two months after Metropolitan Andrei’s death, the Church of Transylvania elected a new primate – the late Metropolitan’s longtime collaborator, Prokopije Ivackovic.

The Austro-Hungarian Empire was a fascinating place for Orthodoxy, with multiple autocephalous Orthodox Churches operating on imperial territory. In Bukovina (at the time part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and today divided between northern Romania and southwestern Ukraine), the local Orthodox population was unusually diverse – majority Romanian, but also large numbers of Ruthenians and Serbs. Until the late 18th century, the Orthodox of Bukovina were under the Church of Moldavia. The Austrians conquered the region in 1774, and in the wake of this, the Habsburg Empire placed the Church of Bukovina nominally under the Serbian Metropolitanate of Karlovci. In practice, though, the state controlled the church: the emperor appointed the local bishop, and parish clergy were assigned by the governor. Neither of these civil authorities were themselves Orthodox.

The Church of Bukovina remained part of the Metropolitanate (and, after 1848, the Patriarchate) of Karlovci until 1873, when the government gave Bukovina permission to establish an independent Metropolitanate of Bukovina and Dalmatia. This new structure would be distinct from both the Serb-dominated Karlovci Patriarchate and the Romanian-dominated Transylvanian Church, both of which were in the Habsburg Empire. The Bukovinans wanted to chart their own course, since their church was ethnically mixed. The Church of Bukovina proclaimed itself autocephalous, a status it claimed until after World War I.

***

By the middle of 1874, the Serbian patriarchal see of Karlovci had been vacant for four and a half years, as the various parties in the church and the Habsburg government could not agree on a candidate. The leading vote-getter, Bishop Stojkovic of Buda, had been rejected by the government, but at a church assembly on May 29/June 11, he received the majority of votes once again. And again, the Austrian government refused to accept his election, this time ordering the assembly to elect someone else. They did, choosing Metropolitan Prokopije Ivackovic, who had been elected primate of the Church of Transylvania less than a year earlier. Remarkably, Prokopije had, ten years before, pushed for an independent Romanian Church to be carved out of the Patriarchate of Karlovci. The Austrians accepted Prokopije’s election, and at long last, Karlovci had a new patriarch.

In his message to the faithful of Transylvania, announcing the news, Prokopije wrote, in part:

[O]verwhelmed by such powerful circumstances, I was left no other choice but to submit and resign, being deeply persuaded that this is for the good of our holy church. And so it was, dearly beloved, that I, albeit heavy-hearted with grief and fully aware of my most serious responsibility, have had to part with You, to discard my archpriesthood field among my most beloved Romanian people, to whom for 21 years I have devoted all my modest powers and care. I have parted with You, I have discarded You — but, to be sure, only with my body; my spirit — it will forever be with You, I will forever follow You with love and all my concern, as required by the bound of the church and by the sincere and intimate communion of the past.

According to the Romanian historian Maria Pantea, Prokopije’s acceptance of the patriarchal throne of Karlovci was viewed by some Romanians as a betrayal, and his election by the Serbs as an attempt to re-impose their Serbian authority over the Church of Transylvania. But this was not a unanimous perspective, as others saw the move as a positive example of inter-Orthodox cooperation.

Having surrendered his see in Transylvania, Prokopije was succeeded by Miron Romanul, who served as Metropolitan of Sibiu until his death in 1898.

***

In April 1877, Russia, in an alliance with Romania, declared war on the Ottoman Empire. The following month, Prince Carol and the Romanian Parliament formally declared Romania’s complete independence from the Ottoman Empire. The war effectively ended in January 1878, and the peace treaty in March established the independence of the Romanian state (along with Serbia and Montenegro, as well as an autonomous Principality of Bulgaria).

On Holy Thursday 1882, which coincided with the Feast of the Annunciation, the hierarchs of the Church of Romania (i.e., Wallachia and Moldavia) blessed new Holy Chrism for the first time in Romanian history. This provoked an angry response from Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim III in July, to which the Holy Synod of Romania responded that it had just as much a right to consecrate its own Holy Chrism as Russia did.

Finally, in 1885, the Ecumenical Patriarchate accepted the fait accompli of Romanian autocephaly, issuing a tomos recognizing the Church of Romania as an autocephalous church.

***

At this point, there were three independent Orthodox Churches with large Romanian populations: The “Romanian Orthodox Church” (Wallachia and Moldavia), plus Transylvania and Bukovina. Those weren’t the only Romanian churches, though. In an 1812 peace treaty between Russia and Turkey, the region of Bessarabia (which includes modern-day Moldova – not to be confused with the different region of Moldavia! – and part of Ukraine) was incorporated into the Russian Empire. The Romanian Metropolitan was made an Exarch of the Russian Orthodox Church, and initially, the indigenous people of Bessarabia were treated with tolerance. This was quite a contrast with the incorporation of Georgia into the Russian Empire, which was happening at the same time: in that case, the Georgian Church was abolished and its bishops were replaced by ethnic Russians, and Russian policy was to suppress Georgian identity, including language. In time, though, the Russian Synod began sending Russian bishops to Bessarabia, and by the end of the 19th century, Russian hierarchs were employing a policy similar to the one in Georgia, restricting the use of the indigenous language in favor of Russian.

In the wake of the 1917 February Revolution in Russia, a Bessarabian church council declared autonomy, retaining a connection with the Russian Church. The council also made Moldovan the only permitted language in church services. Soon enough, though, the Bessarabian/Moldovan church would be incorporated into the unified Romanian Orthodox Church.

***

World War I ended the great empires of the Orthodox world: Russian, Ottoman, and Habsburg. Everyone always forgets the Habsburgs, but as we’ve seen, they were major players in Orthodoxy despite being Roman Catholic themselves. By 1920, the various Romanian regions were unified into a single state, joining together the smaller “Romania” (Wallachia and Moldavia) with Transylvania, Bukovina, Bessarabia, and several other areas. The Orthodox leaders were intimately involved in this process, and church unification was an obvious inevitability. In 1918, a bishop from Romania took control of the church in Bessarabia. The following April, the Church of Transylvania declared itself to be part of the Holy Synod of Romania. In December, a council of bishops chose Bishop Miron Cristea as Primate Metropolitan.

The 1923 Romanian Constitution declared the Romanian Orthodox Church to be the “dominant” church of the state. Romanian Orthodoxy, now unified into a large church structure and backed by an increasingly powerful state, was ascendant. The Romanian state lobbied on behalf of the Ecumenical Patriarchate during the Lausanne Treaty negotiations. Lucian Leustean writes, “During the process of negotiating the treaty, Romania, which enjoyed good relations with both countries [Turkey and Greece], asked Turkey to ensure that the transfer of population stipulated in the treaty would not lead to the abolishment of the Ecumenical Patriarchate.” Soon after this, the Orthodox Churches planned to gather in Jerusalem to commemorate the 1600th anniversary of the First Ecumenical Council. Many in Romania began to advocate for the Romanian Metropolitanate to become a Patriarchate, so that it could attend these celebrations on equal footing with the other leading Orthodox Churches in the world.

In February 1925, the Romanian Holy Synod and then the Romanian Parliament voted in favor of patriarchal status and then sent letters to the other autocephalous churches informing them of this decision. The Ecumenical Patriarchate, grateful for Romania’s help during the Lausanne negotiations, responded quickly and favorably, issuing a tomos recognizing Romania as a Patriarchate on July 30. Ecumenical Patriarch Basil II wrote in a letter to the other autocephalous churches,

Receiving the duties concerning the holy ship entrusted to Us, we found, on the desk of our holy and venerable Synod, the letters of proclamation of March 12 this year concerning this decision of the Holy Orthodox Church of Romania, which awaited our answer.

Although it is clear that the ascension to the patriarchal worth of some of God’s holy Churches in part, according to the strictly canonical ordinance and as the examples of the fathers testify, is subject to the judgment of the ecumenical synod, yet our Great Church of Christ, judging and understanding and the decision of the Holy Orthodox Church of Romania, her daughter and sister in Christ, did not find an insurmountable obstacle for her willingly, using good economy, to give her fraternal consent and to recognize the work already done.

This consent and recognition was made with the confidence that, having other real examples from before, the Great Church of Christ will have in these views, with unanimous opinions and votes, the other Most Holy and Most Honest Patriarchs and Presidents of All Saints. sister Orthodox autocephalous churches and still with the hope that the whole holy orthodox church, gathered in the ecumenical synod or otherwise of the great synod, which, according to the strictly canonical order, has the right to decide in the last resort, will not judge otherwise what is good purpose and for the benefit and glory of the Church have been committed before.

Notably, the Ecumenical Patriarch recognized the elevation of Romania to patriarchal status as “a work already done” by the Romanian Synod (rather than something effectuated by Constantinople). The Ecumenical Patriarch gave his “consent and recognition” of this already-accomplished fact, and then sought the “unanimous opinions and votes” of the other primates, while pointing to a future “ecumenical” or “great” council that would presumably confirm this new status once and for all.

Finally, then, we have the governing structure of the Church of Romania as we know it today: the Patriarchate of Romania, uniting all of the various regions with Romanian populations.

Main Sources

I am indebted to Lucian Leustean, not only for his outstanding published scholarship on this topic (see below), but for taking the time to review this paper and offer his invaluable feedback.

Iulian Dumitrascu, “St. Gregory, Metropolitan of Wallachia,” Basilica.ro, June 22, 2021, https://basilica.ro/en/st-gregory-metropolitan-of-wallachia-hieromartyr-eusebius-the-bishop-of-samosata/

Laurentiu Nicolae Stamatin, “Romanian Orthodox Church in the First Decades of Carol I’s Reign (1866-1885), Codrul Cosminului 17:1 (2011), 95-115.

Lucian N. Leustean, “Eastern Orthodoxy and national indifference in Habsburg Bukovina, 1774-1873,” Nations and Nationalism 24:4 (2018), 1117-1141.

Lucian N. Leustean, “The Romanian Orthodox Church” in Lucian N. Leustean, ed., Orthodox Christianity and Nationalism in Nineteenth-Century Southeastern Europe (Fordham University Press, 2014), 101-163.

Lucian N. Leustean, Orthodoxy and the Cold War: Religion and Political Power in Romania, 1947-1965 (Palgrave MacMillan, 2009).

Dejan Mikavica and Goran Vasin, “Proclamation of Patriarch of Sremski Karlovci Prokopije Ivackovic,” ISTRAŽIVANJA, Јournal of Historical Researches 22 (2011), http://istrazivanja.ff.uns.ac.rs/index.php/istr/article/view/512/531.

Procopiu Ivacicoviciu, “Venerabilului Consistoriu metropolitanu gr. or. romanu in Sibíiu; la manele naltuprésantíei sale parintelui Ioane Popasu, dreptmaritoriu Eppu romanescu alu Caransebesiului, ca celui mai betranu Episcopu alu Ierarchíei romane gr. or. din Ungari’a si Transilvani’a, in Caransebesiu”, in Lumina. Organu Oficiale alu Eparchiei Romane Gr. Or. Aradane 38 (1874).

Maria Alexandra Pantea, “Procopiu Ivacicovici de la episcopie la patriarhie,” Anuarul Institutului Cultural Român din Voivodina (2011), 65-75.

Ion Tutuianu, “Failure of Impropriation of Monastery Possession from Romanian Principalities until 1834,” Acta Universitatis Danubius 6:1 (2013), 95-113.

Good day and all the best from Romania!

It would be interesting to note that Cuza interfered with the Church in such a manner because the greeks were not faithful to the agreements made regarding the funds that should be given over to the Holy places, agreements which had a history dating quite a while back.

Also, in the time of the Phanariot rulers, the greeks imposed their egumens and abused the monasteries economically. Many of them were in ruins or in very bad condition because of this exploitation. The problem of titular greek bishops (given a title of a bishopric that no longer existed) was another thing that made the unification of the Church difficult because of the interference of Phanar in internal affairs. He was forced to take strict and drastic measures in order to assure autonomy and success.

I am sorry for not offering a more detailed explanation, but if needed, I can point to some Romanian Church History college courses I studied as a student at the Dumitru Stăniloae Orthodox Theological Faculty in Iași.

Thank you for your work and I hope that you will be able to write a book on Orthodoxy in America based on your findings, some of which I really enjoyed learning about!

I also apologize if any of the information I provided was misleading or untrue. Pray for me that God may forgive me!

Sincerely in Christ,

Andrei

Before denouncing the secularisation of the monasteries too harshly, it is well to remember that this policy of Prince Alexander John Cuza and his minister Michael Kogălniceanu was one of the last phases of a several-decade campaign to liberate Romania’s numerous black slaves, many of whom, shockingly, were owned by the Church. Who was doing God’s work: the Prince-Liberator, or the monastery responsible for the following bill of sale: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/Category:Slavery_in_Romania#/media/File:Sclavi_Tiganesti.jpg

Hi Dionysius,

It would be useful to correct your comment from “…black slaves…” to “…Roma (Gypsy) servants…”. The state of the nomadic Roma people (not only in the Romanian lands but all over Eastern and Central Europe) was certainly precarious. It included discrimination, persecution, servitude and in many places conflict. In truth, however, there were also situations when the local peoples had to defend themselves from these nomadic groups.

But the greatest interest of Cuza, Kogalniceanu, and the governmental leadership of the time was simply to stop the control of the Greek/Ecumenical Patriarchate over the Church in Romania. The comment by Robert-Andrei Balan is much more accurate in its pursuit.

Blessed Holy Week and Pascha,

Fr Tim