As readers of this website surely know, a large Greek diaspora emerged at the turn of the last century, with hundreds of thousands of Greeks (and other Orthodox Christians) emigrating from their homelands, particularly to the United States. These new immigrants established churches that were loosely tied to various Old Country hierarchies — some looked to the Ecumenical Patriarchate, others to the Church of Greece, still others to local bishops or even (in rare instances) Jerusalem and Alexandria. In 1907, the Ecumenical Patriarchate established a commission to examine the issue of the growing Greek diaspora. Who had authority over these people and their churches? How should the diaspora be administered? This would ultimately lead to a landmark Tomos in 1908, which we’ll publish in due time. But before that, there was a report from the Patriarchal Commission and debate in the Holy Synod of Constantinople. All of this was summarized by the writer G. Bartas in issue 68 (1908) of the French journal Échos d’Orient, which focused on news and events in the Orthodox world. What follows is a rough translation of that article.

***

Along with the modern Jews and Italians, no people has ever emigrated as much as the Greek people. From antiquity, the attraction of the sea, the taste for trade, and the love of adventures pushed the Hellenes to leave their homeland and establish prosperous colonies on all the coasts of the Mediterranean Sea, which would gradually supplant the Phoenician and Carthaginian trading posts and create, in the long run, a most brilliant civilization. The cities located in the interior of the land, in Asia Minor, in Syria, in Egypt, as far as Persia and Arabia, were also inhabited by Greeks and very quickly Hellenized.

The same phenomenon of emigration is reproduced before our eyes. Every year, especially before their military service requirement deadline, young Greeks leave by the thousands the smiling sky and the thin soil of their fatherland, to go and try their fortune elsewhere. The flow of people today tends towards the United States. The year 1902 saw 11,490 Greeks leave for the Port of New York. The year 1903, a little over 13,700. For the general census of Hellenic subjects throughout the world, which the government of Athens is in the process of conducting at the moment, we have, if I am well informed, sent to America 130,000 registration sheets. There is no doubt that this figure is much lower than the number of people to be counted.

The United States is not alone in having Greek colonies. Without speaking about the Greeks who live on the Ottoman territory, one meets them a little everywhere, mainly in the great industrial and commercial centers; some even of these colonies, like that of Venice, are already several centuries old. Now, if, from the civil point of view, the emigrants very easily adopt their new country—without renouncing, moreover, any more than the Jews, their own race—from the religious point of view, it is not the same. Orthodox by religion, they do not want at any price, with very rare exceptions, to go to the Catholic or Protestant churches of the countries that deign to receive them. They therefore have their own churches and chapels for the celebration of their offices and their liturgy.

To whom do these priests, these Churches, and these faithful belong, from the canonical point of view? This is a serious question that has been under study for a long time, without any solution being reached. In fact, apart from the Church of Greece, the four ancient patriarchates and the Cypriot Church, there is no established Greek Orthodox hierarchy.

The Russians indeed have in North America the Diocese of the Aleutian Islands, the holder of which resides in San Francisco and is assisted by two auxiliary bishops. They also have a bishop in Japan. They are going to establish another in Rome for the West, but, while being brothers by religion, while having the same liturgical rite, the Greeks will never decide to attend Russian offices and especially will not depend on a Muscovite bishop.

With the Russians, we must still except the Cypriot Church, which no longer counts; those of Jerusalem and Alexandria, which hardly count, at least for the subject which concerns us; that of Antioch, which already has an Arab bishop, His Grace Raphael, auxiliary to the Russian bishop of San Francisco. Setting aside all these Churches, there remains only the Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople and the Holy Synod of Athens.

It is between these two Churches that the struggle is engaged, about the jurisdiction to exercise on the Greeks of the diaspora or the dispersion. Athens would want everything; Constantinople, although very inclined to concessions, would nevertheless like to keep something. Who will win?

On October 30/November 12, 1907, there was read before the Holy Synod of Constantinople a report presented on this matter by the Metropolitans of Nicomedia, Pelagonia, and Grevena. The report concludes, basing itself on the holy canons — which are not quoted — that all the Greek Churches and communities abroad, not included in the canonical territory of an autocephalous Orthodox Church, depend on the Ecumenical Patriarchate. For the good success of this project, the Commission was of the opinion that the Ecumenical Patriarchate should write to the autocephalous sister Churches to ask the Ecumenical Patriarchate for formal consent for the appointment of hierarchs and clergy in charge of their annexes abroad. In this case, the Ecumenical Patriarchate would have no right to refuse; it would be, in short, a pure formality,

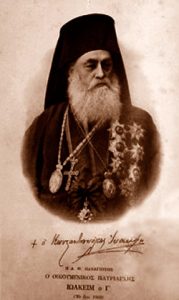

His All Holiness Patriarch Joachim III disagreed. He proposed that, in Europe at least, things remain as they are, with communities everywhere continuing to depend on their own churches. As for the Greek communities in America, they would report directly to the Holy Synod of Athens. After an engaged discussion on this idea, it was decided that the report of the Patriarch’s Commission and advice would be mimeographed and handed over to the members of the Holy Synod, who should study the matter in their own right.

The next day, after reading the minutes, the Patriarch clarified his thoughts and asked that the Venetian colony come under the Ecumenical Patriarchate, because he still intends to establish a high school of theology there for young people who have completed their studies at the Seminary of Halki. Things are there for now.

Maybe this will silence your frequent commentators accusing you (absurdly, in my view) of being “anti-Hellene.”

I must ask one question and make one observational inquity.

First who is Bartas, is he an ethnic Greek? This means alot regarding perspective and paradigms.

Secondly, it does not really clear up the Greek bias perception, what it does do is to again reinforce the perspedtive that the Church of Greece and the Ecumenical Patriarchate do not play nicely in the sand box, and that Christian intercooperation is not part of their agenda. Otherwise, why would the Greeks not go to the Russian Church for services, isn’t being in an Eastern Orthodox Christian Church the Biblical priority and objective? Or is the priority that only being in a Greek Orthodox Church what counts? ( I puposefully left out the adjective Christian).

If the latter statement is true, then we certainly live in a sad, sad, sad, world.