For over a year now, I’ve been telling the story of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the nineteenth century. Here are the previous articles I wrote on the subject:

- The Ecumenical Patriarchate at the Mercy of the Sultan (1821 to 1835)

- The Patriarch Who Defied the Ottoman Empire (1835 to 1840)

- The Ecumenical Patriarchate on the Eve of War (1840 to 1852)

- Orthodoxy’s Holy War and the Ecumenical Patriarchate (1852 to 1856)

- The Longest Schism in Modern Orthodoxy: Bulgarian Autocephaly and Ethnophyletism (1838 to 1872)

- The Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Loss of Its ‘Privileges’ in the Late 19th Century (1877 to 1891)

The previous article in this series dealt with the repeated Ottoman actions to reduce the EP’s civil authority within the declining Ottoman Empire. This all culminated in dramatic fashion around Christmas 1890, when the EP Holy Synod banned all Divine Liturgies in protest. Facing dangerous unrest among an angry Greek Orthodox population who feared the cancellation of Christmas, the Ottomans blinked for a moment, giving the EP a rare victory. Our story paused with the death of Patriarch Dionysius V and the election of Neophytos VIII. We’ll pick things up there, in the early 1890s.

***

The next big provocation came in January 1894, when the Holy Synod of Constantinople was reorganized by order of the Ottoman government. The Ottomans excluded four metropolitans, including the powerful Metropolitan Germanos of Heraclea, and the Russian ambassador wrote privately, “I will exert my influence to ensure that the present Ecumenical Patriarch remains. He is a kind, honest person of goodwill. But I am very afraid that his obvious weakness and lack of experience together with the absence of support and help from his former confidants, especially the Metropolitan of Heraklion, will soon make him a victim of the quarrels and passions which are tearing the church apart.”

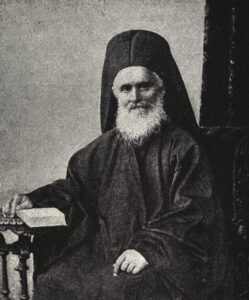

In November 1894, Patriarch Neophytos was forced to resign. According to Adrian Fortescue, Neophytos “was a prelate who really cared for the dignity and independence of his Church, and by way of restoring them he ventured on a feeble attempt at resisting the tyranny of the Porte in canonical matters.” But when Neophytos asked for help from the other Orthodox Churches – in particular, the Church of Russia – he was turned down. By this point the Turks viewed him as a headache, and he was also blamed for failing to heal the Bulgarian schism, which was by now more than two decades old. The Holy Synod and mixed council of Constantinople unanimously determined that Neophytos must resign, which he did.

While the Holy Synod and mixed council of Constantinople were happy to agree to get rid of Neophytos, they had no such unanimity regarding who should succeed him. One contemporary source writes, “After the resignation of Patriarch Neophytos VIII, the Ecumenical Throne was vacant for three months, and many misdeeds took place… greatly diminishing the prestige of the Great Church.” Early in 1895, the Ottoman Minister of Religions intervened and ordered an immediate patriarchal election. Fortescue writes that of the 28 names submitted to the government as nominees, the Minister of Religions eliminated seven, including the popular ex-Patriarch Joachim III. Finally, Anthimus VII was elected, but the trouble wasn’t quite over yet – at his enthronement, the supporters of Joachim III shouted “Anaxios!” Once enthroned, Patriarch Anthimus immediately reached out to the Russian ambassador in Constantinople, asking for the moral and economic support of the Russian Empire.

One of Anthimus’s first notable actions came in August 1895, when he and his Holy Synod issued an encyclical replying to recent overtures by Pope Leo XIII that the Orthodox submit to the Pope. The EP encyclical is one of the most comprehensive critiques of Latin errors, including papal supremacy, issued by an Orthodox synod in modern times.

***

In 1895, two controversies regarding the appointment of metropolitans erupted at the same time. First, the Greek Metropolitan of Prizren, in Kosovo, died. This part of the Serbian Orthodox community was under the Ecumenical Patriarchate, and they demanded that the Phanar appoint a native Serb to the throne. This was successful, and in 1896 Metropolitan Dionisije Petrovic was enthroned. Soon after this, the Greek Metropolitan of Skopje also died. This time, the Ecumenical Patriarchate quickly appointed a Greek, Metropolitan Ambrose, to succeed him. When Ambrose arrived in Skopje, his cathedral was locked and the native Serbian and Macedonian population refused to accept him. Turkish soldiers forced the church open and Ambrose entered and served the Divine Liturgy in Greek, but, as Fortescue describes it, “in the presence of no one save the Turks who stood in the nave with fixed bayonets to keep the Serbs from a riot.” In the months that followed, the Serbs and Macedonians continued to reject Metropolitan Ambrose, who finally returned to Constantinople in July 1897. At this point the Phanar relented and elected a native Serb, Firmilian – but they refused to consecrate him, leaving Firmilian and the Skopje church in limbo for the next four years.

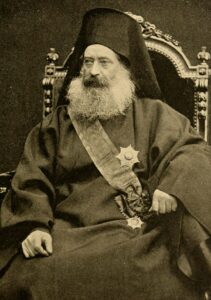

Ecumenical Patriarch Anthimus was blamed for betraying the Greek cause in Skopje, and as a result, in February 1897, he was deposed. In April he was succeeded by Constantine V, whom Fortescue describes as “one of the best of all the later Oecumenical Patriarchs. He set about reforming the education of priests, insisted that the services of the Church should be celebrated with the proper reverence, and modified some of the incredibly pretentious etiquette which his court had inherited from the days of the old Empire.” A quarter century earlier, Constantine had been the secretary at the 1872 council that condemned ethno-phyletism and anathematized the Bulgarian Schism. Lora Gerd describes him as having no sympathies toward the Slavs (Bulgarians, Serbs, etc.), and notes, “Like many other Eastern patriarchs he wanted good relations with Russia and to receive material support from it but without supporting Russian policy in the Near East.”

On September 6, 1898, a Muslim mob massacred hundreds of Christians – mostly Greek Orthodox, but also including some Armenians – in the city of Heraklion (Candia) in Crete. The mob also killed the British vice-consul and his family. In response, the Great Powers demanded that the Sultan withdraw all Ottoman troops from the island. In November the British military entered Crete, forced the last Ottoman soldiers out, and ended Turkish rule in Crete. The following month, Crete was formally established as an autonomous state nominally still under the Ottoman Empire. This immediately opened up the question of the relationship between the Church of Crete and the Ecumenical Patriarchate – a conflict that would take the better part of two years to resolve. At first, the Ecumenical Patriarchate tried to appoint a new Metropolitan for Crete unilaterally, but he was rejected by the revolutionary Cretan government, which took the position that Crete’s bishops could no longer be appointed by a Patriarchate that was still under Ottoman control. Within Crete itself, many agreed with this argument, but others wanted to maintain their existing tie to Constantinople. Finally, thanks to the intervention of a couple of key Greek political leaders – including Eleftherios Venizelos, the future Prime Minister of Greece – a deal was struck: Crete would be semi-autonomous, with the power to nominate three candidates for Metropolitan, while the Ecumenical Patriarchate would choose the winner. Using this method, a new Metropolitan was chosen in May 1900, and in October, the Cretan government and the Ecumenical Patriarchate signed a formal agreement, establishing Crete’s new ecclesiastical reality.

***

Meanwhile, tensions worsened between the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Russian church and state. At a Holy Synod meeting in January 1900, Ecumenical Patriarch Constantine spoke cryptically of a “mystical power” that was counteracting the Patriarchate in its struggle against church closures in Macedonia and confiscation of church properties by the Muslims. The Russian ambassador in Constantinople interpreted this to be an accusation against the Russian Empire. In November, Patriarch Constantine sent a letter of protest to Tsar Nicholas II, complaining about Russian activity in the Near East and the “plans of pan-Slavism.”

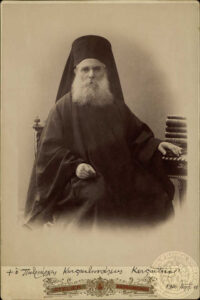

In March of 1901 supporters of former Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim III began to push for their man to return to the throne. Joachim represented a more Russian-friendly option compared to the openly anti-Russian Constantine V. Joachim had the support of both the Russian and Greek governments; the one threat to his candidacy was the Ottoman state, which could again exclude his name from the candidate list in the event of a patriarchal election.

By April, it was clear that Constantine V’s days as Patriarch were numbered. Both the Holy Synod and the mixed council of Constantinople demanded his resignation. Constantine resisted, and initially he had the support of the Ottoman government. Confusion erupted when a Greek newspaper in Constantinople reported that Constantine had already resigned. The Ottoman government promptly imprisoned the newspaper’s editor. During Holy Week, numerous Metropolitans in Constantinople again came to the Patriarch and demanded his resignation. He again refused and carried on with Holy Week services, which were boycotted by the bishops who opposed him. At this point the Holy Synod was in a de facto state of schism, with the majority anti-Constantine party refusing to recognize him as Patriarch. In the end the Turks gave in, withdrawing their support, and Constantine was forced out.

He was succeeded by Joachim III, who, at long last, was re-elected to his second term as Patriarch in June 1901 with a narrow plurality of 83 votes (his two opponents had 72 and 69 votes, respectively). This marks the beginning of what was in many respects the last hurrah of the old Ottoman Ecumenical Patriarchate — the age of “Joachim the Magnificent.”

Main Sources

Theocharis E. Detorakis, History of Crete (Iraklion, 1994) (John C. Davis, trans.).

Lora Gerd, Russian Policy in the Orthodox East: The Patriarchate of Constantinople (1878-1914) (De Gruyter Open, 2014).

Adrian Fortescue, The Orthodox Eastern Church, 2nd ed. (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1908).

Robert Holland and Diana Markides, The British and the Hellenes: Struggles for Mastery in the Eastern Mediterranean 1850-1960 (Oxford University Press, 2006).

Demetrius Kiminas, The Ecumenical Patriarchate: A History of Its Metropolises with Annotated Hierarch Catalogs (Wildside Press, 2009).

Georgios Papadopoulos, Hē synchronos hierarchia tēs Orthodoxou Anatolikēs Ekklēsias (1895).

Davide Rodogno, Against Massacre: Humanitarian Interventions in the Ottoman Empire: 1815-1914 (Princeton University Press, 2012), 221.