On February 28, 2020, the Bulgarian Orthodox Church will celebrate the 150th anniversary of the creation of an independent Bulgarian Church (known as the “Bulgarian Exarchate”) by decree of the Ottoman sultan. For centuries up to that point, the Bulgarian Orthodox living in the Ottoman Empire had been under the jurisdiction of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. This was not a happy arrangement: the Bulgarians complained that their Greek overlords imposed Greek languages and practices, and they longed to attain self-governance. With the Ottoman Empire weakening, the Sultan ultimately decided to make a concession to the large Bulgarian minority in his empire, creating a new jurisdiction — the Bulgarian Exarchate. From the Bulgarian perspective, this was a restoration of the Bulgarians’ old Patriarchate, which had been suppressed centuries earlier. From the Greek perspective, this was an act of schism and even heresy.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate rejected the Bulgarian Exarchate as uncanonical, ultimately calling the 1872 Council of Constantinople, which condemned “ethno-phyletism” as a heresy and anathematized the leaders of the Bulgarian Exarchate. Not all of the Orthodox Churches participated in the 1872 Council or accepted its decisions — most notably, the Russian Orthodox Church supported the Bulgarians — and the Bulgarian Church remained in an uncertain state for the next seven decades, out of communion with, and unrecognized by, Constantinople and the other Greek Churches. It was not until 1945 that the Bulgarian Church reconciled with the Ecumenical Patriarchate and normalized its status among the world’s autocephalous churches.

Back in 2012, I published a series of contemporaneous accounts of the Bulgarian Schism, written by an American Protestant in Istanbul and published in the Methodist Quarterly Review. Today, I’m republishing all of these accounts below.

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, July 1870

THE EASTERN CHURCH — THE BULGARIAN QUESTION. — Among the most important questions which have agitated the Eastern Churches since the beginning of the present century is the re-construction of a national Bulgarian Church, which is to remain united with the Patriarchate of Constantinople and other parts of the Greek Church in point of doctrine, but to maintain an entire independence in point of administration. This question has obtained a political, as well as an ecclesiastical, importance, as Russia, France, and other European powers have tried to make capital out of it. A decree of the Turkish Government, issued in February, 1870, appears to decide the main point which was at issue. As important results may follow this decision, a brief history of the Bulgarian question will aid in a proper understanding of the situation it now occupies, and of the hopes that are entertained by the Bulgarians with regard to their future.

When the Bulgarians, in the ninth century, under King Bogaris, became Christians, the new missionary Church was placed under the supervision of the Greek Patriarch. About fifty years later King Samuel established the political independence of the Bulgarian nation and the ecclesiastical independence of the Bulgarian Church. But after his death, the Church was again placed under the Greek Patriarch, and did not regain the enjoyment of ecclesiastical independence till the latter part of the twelfth century. After the conquest of the country by the Turks, in 1393, many of the Bulgarians for a while became, outwardly, Mohammedans; but, as religious freedom increased, returned to their earlier faith, and the Bulgarian Church was made an appendage to that of Constantinople. Good feeling prevailed then between the Greeks and the Bulgarians, and the Sultan filled the Bulgarian Sees with Greek prelates, who were acceptable to the people. As the Bulgarian nobility was exterminated, and the people oppressed by wars which followed, there was, until the beginning of the present [19th] century, scarcely a single voice raised against the foreign Episcopate. But the national feeling began to assert itself about fifty years ago, and the Greek Patriarch was compelled to authorize several reforms. Abuses continued, however, and the national feeling increased, so that the Patriarch was obliged, in 1848, to approve the erection of a Bulgarian Church, and of a school for the education of priests, in the capital. The demand of the Bulgarians for a restoration of their nationality, in 1856, again aroused the slumbering zeal of the Greeks, and the differences between the two nationalities have continued very active up to the present time. The Porte, in 1862, named a mixed commission, to investigate and settle the inquiries. It proposed two plans of adjustment. According to one of these plans, the Bulgarian Church was to name the Bishops of those districts in which the Bulgarian population was a majority. The other plan accorded to the Bulgarians the right to have a Metropolitan in every province, and a Bishop in every diocese, where there is a strong Bulgarian population. Both plans were rejected, and the Turkish Government, having been to considerable pains for nothing, left the contending parties to settle the controversy in their own way.

Accordingly the Greek Patriarch, in 1869, proposed a General Council, and solicited the different Churches of the Greek Confession for their opinions and advice on the subject. Greece, Roumania, and Servia declared themselves in favor of the Council. On the other hand, the Holy Synod of Petersburgh, for the Russian Church, declared the claims of the Bulgarians to be excessive, and that, although it considered a Council the only lawful means of settling the points at issue, it feared a schism if the demands of the Bulgarians were complied with, and was further afraid that the fulfillments [sic] of the demands of the canons would be refused, and advised the continuance of the status quo. The Greek Patriarch, being unwilling to solve the question, the Turkish Government took the matter into its own hands, and in February, 1870, issued a decree which establishes a Bulgarian Exarch, to whom are subordinate thirteen Bulgarian Bishops, whose number may be increased whenever it may be found necessary. The Turkish Government has tried to spare the sensibility of the Greeks as much as possible, and has, therefore, not only withheld from the head of the Bulgarian Church the title of Patriarch, but has expressly provided that the Exarch should remain subordinate to the Patriarch of Constantinople. Nevertheless the Patriarch has entered his solemn and earnest protest against the scheme. His note to the Grand Vizier, which is signed by all the members of the Holy Synod of Constantinople, is an important document in the history of the Greek Church, and reads as follows:

To His Highness the Grand Vizier: — Your Highness was pleased to communicate to the Patriarchate, through Messrs Christaki, Efendi, Sagraphras, and Kara-Theodor, the Imperial firman, written upon parchment, which solves the Bulgarian question after it had been open during ten years. The Patriarchate, always faithfully fulfilling its duties toward the Emperor, whom the Lord God has given to the nations, has at all times remained foreign to any thought that the decrees of the Sublime Sovereign in political questions should not be obeyed. The Oriental Church obeyed with cheerfulness and respect the legitimate Sovereigns. The latter, on their part, have always respected the province which belongs to the ecclesiastical administration. The Sultans, of glorious memory, as well as their present fame-crowned successor, (whose strength may be invincible,) have always drawn a marked boundary-line between civil and ecclesiastical authority; they recognized the rights, privileges, and immunities of the latter, and guaranteed it by Hatti-Humayums. They never permitted any one to commit an encroachment upon the original rights of the Church, which, during five centuries, was under the immediate protection of the Imperial throne.

Your Highness: If the said firman had been nothing but the sanction of a Concordat between the Patriarchate and the Bulgarians, we should respect and accept it. Unfortunately, things are different. Since the firman decides ecclesiastical questions, and since the decision is contrary to the canons, and vitally wounds the rights and privileges of the Holy See, the Patriarchate cannot accept the ultimatum of the Imperial Government. Your Highness: Since the Bulgarians obstinately shut their ears to the voice of that reconciliation which we aim at, and since the Imperial Government is not compelled to solve an ecclesiastical question in an irrevocable manner; since, finally, the abnormal position of affairs violates and disturbs ancient rights, the Ecumenical Patriarchate renews the prayer, that the Imperial Government may allow the convocation of an Ecumenical Council, which alone is authorized to solve this question in a manner legally valid and binding for both parties. Moreover, we beseech the Imperial Government that it may take the necessary steps which are calculated to put an end to the disorder which disturbs the quiet within our flock, and which can chiefly be traced to the circulars of the Heads of the Bulgarians (dated the 15th of the present month). The Ecumenical Patriarchate enters its protest with the Imperial Government against the creation of these disturbances.

Written and done in our Patriarchal residence, Mar. 24 (old style), 1870.

(Signed) GREGORY CONSTANTINE, Patriarch.

(Signed) All the members of the Holy Synod.

The note of the Patriarch and his Synod indicates that they are aware that, sooner or later, the national demands of the Bulgarians must be granted; and their chief concern now is to obtain as large concessions for the supremacy of the Patriarchal See as possible.

A peaceable and a speedy solution of the difference is the more urgent, as during the last ten years the heads of the Roman Catholic Church in Turkey, aided by the diplomatic agents of the French Government, have made the most strenuous efforts to gain a foothold among the Bulgarians, and to establish a United Bulgarian Church. Nor have these efforts been altogether unsuccessful. Several years ago the Pope appointed the Bulgarian priest, Sokolski, the first Bishop of those Bulgarians who had entered the union with Rome, and who constituted a nucleus of the United Bulgarian Church, which, like the other united Oriental Churches, accepts the doctrines of the Roman Catholic Church, but is allowed to retain the ancient customs of the ancient national Church, (marriage of the priests, use of the Sclavic [sic] language at divine service, etc.). Bishop Sokolski was quite on a sudden carried off from Constantinople, (as was commonly thought by Russian agents,) and has never been heard of since. In 1855, Raphael Popof was consecrated successor of Sokolski; he still lives, as the only United Bulgarian Bishop, is present at the Vatican Council. He resides at Adrianople, and under his administration the membership of the United Bulgarian Church has increased (up to 1869) to over 9,000 souls, of whom 3,000 lives in Constantinople, 2,000 in Salonichi and Monastir, 1,000 in Adrianople, and 3,000 in the vicinity of Adrianople. The clergy of the Church, in 1869, consisted of ten secular priests.

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, April 1871

The Bulgarian Church Question, to the earlier history and importance of which we have referred in former numbers of the “Quarterly Review” led in the year 1870 to very important developments. The demand of the Bulgarians to have Bishops of their own nationality, and a national Church organization like the Roumanians and the Servians, was, in the main, granted by the imperial firman of March 10. The substance of the eleven paragraphs is as follows:

- Article I. provides for the establishment of a separate Church administration for the Bulgarians, which shall be called the Exarchate of the Bulgarians.

- Article II. The chief of the Bulgarian Metropolitans receives the title of Exarch, and presides over the Bulgarian Synod.

- Article III. The Exarch, as well as the Bishops, shall be elected in accordance with the regulations hitherto observed, the election of the Exarch to be confirmed by the oecumenical Patriarchs.

- Article IV. The Exarch receives his appointment by the Sublime Porte previous to his consecration, and is bound to say prayer for the Patriarch whenever he holds divine service.

- Article V. stipulates the formalities to be observed in supplicating for the appointment (installation) by the Sublime Porte.

- Article VI. In all matters of a spiritual nature the Exarch has to consult with the Patriarch.

- Article VII. The new Bulgarian Church, like the Churches of Roumania, Greece, and Servia, obtains the holy oil (chrisma) from the Patriarchate.

- Article VIII. The authority of a Bishop does not extend beyond his diocese.

- Article IX. The Bulgarian Church and the bishopric (Metochion) in the Phanar are subject to the Exarch, who may temporarily reside in the Metochion. During this temporary residence he must observe the same rules and regulations which have been established for the Patriarch of Jerusalem during his residence in the Phanar.

- Article X. The Bulgarian Exarchate comprises fourteen dioceses: Rustchuk, Silistria, Schumia, Tirnovo, Sophia, Widdin, Nisch, Slivno, Veles, Samakovo, Kustendie, Vratza, Lofdja, and Pirut. One half of the cities of Varna, Anchialu, Mesembria, Liyeboli, and of twenty villages on the Black Sea, are reserved for the Greeks. Philippople has been divided into two equal parts, one of which, together with the suburbs, is retained by the Greeks, while the other half, and the quarter of Panaghia, belongs to the Bulgarians. Whenever proof is adduced that two thirds of the inhabitants of a diocese are Bulgarians, such diocese shall be transferred to the Exarchate.

- Article XI. All Bulgarian monasteries which are under the Patriarchate at the present time shall remain so in the future.

The Greeks of Constantinople where indignant at this firman, because they were well aware that its execution would put an end to the subordinate position in which they have thus far kept the Bulgarians. They demanded that the Patriarch should either reject it or resign. The Synod which was convened by the Patriarch in April declared that the firman was in conflict with the canons of the Church, and that an Ecumenical Council should be summoned to decide the question. The Patriarch accordingly notified the Turkish government that he could not accept the firman, and that, therefore, he renewed his petition for the convocation of an Ecumenical Council. The Bulgarian committee, on the other hand, issued a circular in which the solution of the question by the firman was declared to be entirely satisfactory, and corresponding with their just demands. They pointed out that the principal demand of the orthodox Bulgarians had been that their Churches and bishoprics be intrusted to a clergy familiar with the Bulgarian language, and that they did not understand how the Patriarchate could designate as unevangelical so legitimate a desire. The Patriarch, in a letter to the Grand Vizier, declared that he could retain his office only if the government granted the convocation of the Ecumenical Council. The endeavor of Ali Pasha to induce the Patriarch to desist from his demand proved of no avail. The twelve Bishops constituting the Synod of Constantinople sent a synodic letter to the Porte, in which they implore the government to settle the Bulgarian Church question on the basis proposed by the Patriarch in 1869. The government now yielded. Ali Pasha invited the Patriarch to send to the government a programme of the question to be discussed by the Ecumenical Synod. To this the Patriarch replied as follows:

We had the honor of receiving the rescript which your highness has condescended to forward to us, as a reply to our letter and the Maybata of the Synod of Metropolitans. We perceive that we shall be authorized to convene the Ecumenical Council, to which will appertain the final solution of the Bulgarian question by canonical decision. Your highness expresses the desire to know beforehand the objects and the limits of the deliberations of the Council, and invites us to submit a programme of the same. We have the honor of informing you that the Ecumenical Council, for whose convocation we requested the authorization of the imperial government, will have to investigate and to adjust the controversy which has arisen between the Patriarchate and the Bulgarians. Your highness is aware that said controversy resulted partly from the circumstance that the Bulgarians did not consider satisfactory the concessions which we granted them in regard to the administration of the Church, partly from the fact that the Bulgarians demand something which is in direct opposition to the spirit of our faith and to the commands of the holy canons, although they pretend that their proposals are not at all in contradiction to the holy laws. Thus the labors of the Council, which will not touch on any secular question, will be strictly limited to deliberations on the Bulgarian question; the demands of the Bulgarians, as well as the concessions made by the Patriarchate, will be minutely and impartially scrutinized, upon which the Council will come to a decision in accordance with the spirit of the canons, from which there can be no appeal.

Done and given at our Patriarchal residence on November 16, 1870.

GREGORY

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, April 1872

The Bulgarian Church question continued to agitate the Greek Church of Turkey throughout the year 1871. The committee of six Bulgarian bishops, which, in accordance with the firman of February 26, 1870, met in Constantinople, in union with prominent Bulgarian notables of the Turkish Senate, in order to prepare a draft for the organization of an autonomous Bulgarian exarchate, (the main points of this draft were given in the Methodist Quarterly Review, 1871, p. 319,) drew up at the same time an act for the election, by the committees of clerical and lay deputies of a national assembly, to meet in Constantinople in April, 1871, for the rectification of the Church statutes.

An active discussion took place in this assembly between those who advocated the application of the regulations of the old Greek Church to the new exarchate, and a progressive party which favored the introduction of the presbyterial system. The principal journal of “Young Bulgaria,” under the leadership of the “Makedonia” of Slavejkov, supported the party of progress. After long and animated debates the Church assembly declared in favor of the participation of the laity in the administration of the affairs of the Church, the establishment of the salaries of the higher and lower clergy, and the exclusive application of all surplus of ecclesiastical taxes to the elevation of popular instruction and the establishment of higher schools. It was decided also, by a vote of 28 to 15, that the exarch should be appointed, not for life, but for a term of five years. The place where he should reside was left an open question, almost equally strong reasons being presented in favor of his residence at Constantinople and in one of the larger towns near the center of the exarchate. The discussion of the draft of the Church Constitution was finished on May 26, and it was presented to Ali Pasha by three deputies of the assembly — Hadshi Ivantshov, Pentchov Gyordaki, and Dr. Tchomakov.

The Greek Patriarch, supported by the diplomatic influence of Russia, came again forward in opposition to the Sultan’s well-intentioned measures for his Bulgarian subjects, with the demand that the Bulgarian Greek Church conflict should not be regarded as an administrative question, but as one of canon law, and that it should be left to the exclusive decision of an ecumenical council. He protested against all the acts of the Bulgarian National Assembly as uncanonical and unconstitutional. In the contemplated ecumenical council the patriarchate would be sure of a majority. The few Bulgarian bishops would be easily silenced by the numerous Hellenic bishops of the Greek Churches of Constantinople, Jerusalem, Alexandria, Antioch, and Cyprus, and the continued Hellenization of the Bulgarian people would even receive the canonical approbation of the council, against which, as the Patriarch had said in a letter (November 4, 1870) to Ali Pasha, there is no appeal.

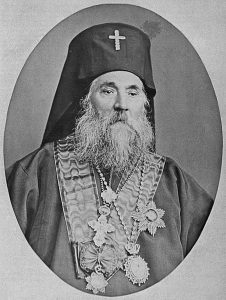

In the meantime, however, the Patriarch Gregory VI. had laid himself open to censure by his undissembled animosity against the Slavic people and his opposition to the commands of the Turkish Governments. Abandoned by the Governments of Russia and Servia, he had no alternative but to accept the suggestion of Ali Pasha, and resign the patriarchate. Antim Kutalianus succeeded him on the 18th of September. Being of a more conciliatory disposition than his predecessor, he sought, as early as October, to engage in negotiations with influential Bulgarians for a compromise of difficulties. These negotiations have been of a more conciliatory character, but from what has transpired respecting them they do not seem likely to allay the long-increasing division in the Church. Antim insists upon giving the patriarchate control of the appointment of the Bulgarian exarch, upon the levy of a tax of a piaster upon each Bulgarian household, and upon the repeal of the tenth section of the Sultan’s firman, which permits districts with a mixed population of Greek and Bulgarians to be attached to the Bulgarian exarchate upon the vote of the majority. The opposition of the patriarchate to this paragraph is easily explained, since it threatens it with a serious loss of moral and material power — a loss which it is not well able to bear since the Servian and Roumanian Churches have been cut off from their dependence upon it. On the other hand, it is natural that the Bulgarians should insist upon its being retained, as its operation will be to promote the continual growth of their exarchate in territory and power.

Members of the Bulgarian National Assembly, among them the deputies from Adrianople, Rustchuk, etc., and the Bulgarian community at Constantinople, have protested earnestly against further continuance of the negotiations with the Patriarch on this basis, to which he adheres obstinately. The decision on the whole subject, however, rests solely with the Porte.

A new conflict between the Bulgarians and the Patriarchate arose when, at the festival of Epiphany, 1872, three Bulgarian bishops, in order to show their independence, celebrated mass, in spite of the prohibition of the Patriarch, in the Bulgarian Church of Constantinople. The patriarch on the next day made a full report of the occurrence to the Turkish Government, which exiled the three Bishops. He also called a meeting of the great National Council, to which he explained the facts in the case and read the report. The Council resolved to publish a proclamation to the nation and to distribute it all over the country.

The Bulgarians were not agreed as to the best course to be now pursued. The Young Bulgarians insisted on the immediate rupture of all negotiations with the patriarchate, and applied to the Porte for the immediate appointment of a Bulgarian exarch. With this request the Porte, however, declined to comply. The more moderate party among the Bulgarians lamented the acts of the three bishops, and demanded the continuation of the negotiations with the patriarchate.

Soon, however, the Turkish Government was prevailed upon to take, once more, sides with the Bulgarians. In February, 1872, a decree of the Grand Vizier proclaimed that the Turkish Government, in consideration of the efforts of the Ecumenical Patriarchate to bring on splits between the Greek and the Bulgarian population, which the Porte had endeavored to prevent, would not establish the Bulgarian exarchate in accordance with the imperial firman. The responsibility for this measure would wholly rest with the patriarchate by which it had been provoked. It is also announced that a new Bulgarian Church Congress will assemble in Constantinople to carry out the provisions of the imperial firman.

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, January 1873

The rupture between the Greek Patriarch of Constantinople and the Bulgarian nation (see “Methodist Quarterly Review,” 1872, p. 329) became complete by the election, in March, 1872, of Bishop Anthim as Exarch, or head of the national Bulgarian Church. The Exarch at once made efforts to bring about an understanding with the Patriarch. The latter replied that he would give a respite of forty days, after the lapse of which he must return to the orthodox Church, and during which he must abstain from exercising any episcopal function, under penalty of canonical law.

The Exarch indeed abstained from all ecclesiastical functions, although the Passover of the Greek Church took place within this period. But in the latter part of May the Exarch yielded to the pressure brought upon him by the leaders of the national Bulgarian party, and solemnly released the three Bulgarian bishops who, in January, 1872, had been excommunicated by the Patriarch, from the excommunication. This induced the Patriarch to convoke a meeting of his synod and of many prominent laymen, which declared the negotiations with the Bulgarians to be at an end, and Anthim to have incurred the canonical censures. On the other side, the Exarch, on May 24, left out in the liturgy the prescribed mention of the Patriarch, and substituted for it the words “the orthodox episcopate,” which immediately called forth the reading of a pastoral letter by the Patriarch, excommunicating Anthim and pronouncing the great anathema against the three Bulgarian bishops.

Notwithstanding these measures, the Bulgarian Church consolidated itself more and more. The Exarch soon consecrated a new bishop, and at Wodina, in Macedonia, the Bulgarians expelled the Greek bishop, and declared that, in accordance with Article X of the firman establishing the Bulgarian exarchate, (by which article it is provided that two thirds of the inhabitants of a diocese have the power of demanding the connection of the diocese with the exarchate,) they would join the Bulgarian Church.

On September 10 the “Great Synod” of the Church met in Constantinople. All the Patriarchs and twenty-five archbishops and bishops were present. The Synod soon declared “phyletism,” that is, the distinction of races and nationalities within the Church of God, as contrary to the doctrine of the Gospel and of the Fathers, and excluded six Bulgarian bishops and all connected with the exarchate from the Church. All the bishops signed the decree except the Patriarch of Jerusalem, who left the Synod before its close, and was therefor insulted by the Greek population of Smyrna, in Asia Minor, who received him with shouts of “Traitor!” “Muscovite!” The following is a translation of the decree of the Synod, which will remain an important document in the annals of the Greek Church:

Decree of the Holy and Grand Council, assembled at Constantinople in the month of September, in the year of grace 1872.

The Apostle Paul has commanded us to take heed unto ourselves and to all the flock over the [sic] which the Holy Ghost hath made us overseers, to govern the Church of God, which he hath purchased with his own blood; and has at the same time predicted that grievous wolves shall enter among us, not sparing the flock, and that of our own selves shall men arise speaking perverse things to draw away disciples after them; and he has warned us to beware of such. We have learned with astonishment and pain that such men have lately appeared among the Bulgarian people within the jurisdiction of the Holy Ecumenical Throne. They have dared to introduce into the Church the idea of phyletism, or the national Church, which is of the temporal life, and have established, in contempt of the sacred canon, an unauthorized and unprecedented Church assembly, based upon the principle of the difference of races. Being inspired in accordance with our duty, by zeal for God and the wish to protect the pious Bulgarian people against the spread of this evil, we have met in the name of our Saviour Jesus Christ. Having first besought from the depths of our hearts the grace of the Father of light, and consulted the Gospel of Christ, in which all treasures of wisdom are hidden, and having examined the principles of phyletism with reference to the precepts of the Gospel and the temporal constitution of the Church of God, we have found it not only foreign, but in enmity to them, and have perceived that the unlawful acts committed by the aforesaid unauthorized phyletismal assembly, as they were severally recited to us, are one and all condemned.

Therefore, in view of the sacred canons, whose rulings are hereby confirmed in their whole compass; in view of the teachings of the apostles, through whom the Holy Ghost has spoken; in view of the decrees of the seven Ecumenical Councils, and of all the local councils; in view of the definitions of the Fathers of the Church, we ordain as follows:

Art. 1. We censure, condemn, and declare contrary to the teachings of the Gospel and the sacred canons of the holy Fathers the doctrine of phyletism, or the difference of races and national diversity in the bosom of the Church of Christ.

Art. 2. We declare the adherents of phyletism, who have had the boldness to set up an unlawful, unprecedented Church assembly upon such a principle, to be foreign and absolutely schismatic to the only holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church. There are and remain, therefore, schismatic and foreign to the Orthodox Church the following lawless men whoh have of their own free will separated themselves from it, namely, Hilarion, ex-Bishop of Makariopolis; Panaretes, ex-Metropolitan of Philippopolis; Hilarion, ex-Bishop of Sostra; Anthimos, ex-Metropolitan of Widdin; Dorothea, ex-Metropolitan of Sophia; Partheonius, ex-Metropolitan of Nyssava; Gennadius, ex-Metropolitan of Melissa, before deposed and excommunicated; together with all who have been ordained by them to be archbishops, priests, and deacons; all persons, spiritual and worldly, who are in communion with them; all who act in co-operation with them; and all who accept as lawful and canonical their unholy blessings and ceremonies of worship.

While we pronounce this synodal decision, we pray to the God of mercy, our Lord Jesus Christ, the head and founder of our faith, that he will preserve his holy Church from all dangerous new doctrines, and that he will keep it pure, spotless, and fast, on the foundations of the apostles and the prophets. We pray him to grant the grace of repentance to those who have separated themselves from her, and have founded their unauthorized Church assembly upon the principle of phyletism, so that they may some day nullify their acts, and return to the only holy, Catholic, and Apostolic Church, in order with all the orthodox to praise God, who came upon the earth to bring peace and good-will to all men. He it is whom we shall honor and worship, with the Father and the Holy Ghost, to the end of time. Amen.

The decree is signed by his Grace the Ecumenical Patriarch and the three former Patriarchs, the Pontiff and Patriarch of Alexandria, the Patriarch of Antioch, the Archbishop of Cyprus, and by twenty-five metropolitans and bishops.

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, July 1873

The excommunication of the Bulgarians by the Holy and Grand Council of Constantinople, in September, 1872, (see “Methodist Quarterly Review,” January, 1873, p. 148,) soon created new troubles. The Greeks of Turkey and Greece gave to the decree of excommunication a fanatical support. The refusal of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Kyrillos, to sign the decree, called forth on the part of the clergy and the people of his patriarchate the greatest indignation. A synod of bishops of the patriarchate of Jerusalem at once met in Jerusalem, admonished their Patriarch to submit to the declaration of the Council, and when he definitively refused, deposed him from office. The following translation of his official decree of deposition is a very interesting contribution to the recent history of the Greek Church:

To-day, Tuesday, November 7, of the year 1872, in the twelfth hour, all the episcopal members of the Holy Synod of Jerusalem, after assembling in the hall of the synodal sessions of the monastery of the Holy Sepulcher, and after taking into consideration the last definitive answer of his Holiness, the Patriarch, Kyrillos II., relative to the acceptance of the resolution of the Grand and Holy Council legally and canonically convoked at Constantinople — by which resolution phyletism (that is, the distinction of races and nationalities in the Church) was rejected and condemned, and all who approved this phyletism, and who, inspired thereby, have held up to this day illegal and clandestine meetings, were declared to be schismatics — have unanimously decreed and do decree as follows:

In consideration that his Holiness — trampling under foot all that he had written in his synodal letter of January 24, 1869, to the Grand Church — not only acted arbitrarily in Constantinople and refused to join in the recognition of the Grand Council, but that he also, in Jerusalem, obstinately, and without sufficient reason, opposed to the invitations and prayers addressed by us to him the refusal to submit with us to the resolution of the Grand Council;

In consideration of all this, we consider him as having incurred the ecclesiastical censures which are expressly contained in the said resolution of the Grand Council, and as being, de facto, schismatic. And we find ourselves in the sad and painful necessity to take back the oath of submissiveness and obedience taken by us toward him, and henceforth to break off all connection and communion with him, and we shall never more perform any function with him, or in any respect act with him, and we shall no longer recognize him as head, and as our lawful and canonical shepherd. In confirmation of which the present act has been compiled and entered into the great book of the Patriarchal Throne of Jerusalem. Moreover, copies of this act have been sent to the Grand Church and to all independent Orthodox Churches.

Both the Patriarch of Constantinople and the Turkish Government, which was likely notified of the resolution of the Council of Jerusalem, recognized the deposition of the Patriarch and gave permission for the election of a new Patriarch. But before this took place Jerusalem was the scene of considerable agitation. The deposed Patriarch refused to recognize the lawfulness of his deposition, and declared his intention to celebrate, on November 23, vespers in the Church of the Holy Sepulcher. The clergy and the monks refused to assist him. From the surrounding country an excited crowd of adherents of the Patriarch, led by the Russian dragoman, invaded Jerusalem, spreading considerable alarm among the opponents of the Patriarch. Police soldiers entered the cells of the monks in order to drag them before the Patriarch. As the monks offered resistance the state of siege was declared, and the monks shut up in the monastery of the Holy Sepulcher. The Patriarch, in the evening, and again on the next day, repaired to the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, attended by the Russian and Greek consuls.

When the consuls of the other Powers asked the Governor of Jerusalem for the cause of this uncommon movement, he replied that the Greeks wished to protect the Patriarch who had been deposed by his clergy, and that he (the Governor) regarded it as his duty to support the Patriarch against the revolutionary clergy. The Consul-General of Germany replied that the Governor seemed to him to exceed his powers, for the organic statutes of the Patriarchate provided for the election of the Patriarch by the clergy who, therefore, had also the power to depose him, while the laity were nowhere mentioned. The Governor then confessed that he was not free, and that the Russian consul had threatened him with deposition in case he should fail to support the Patriarch. Appeal was then made to the Turkish government; the consuls reported to their Governments, and the clergy elected a deputation to go to Constantinople. The Porte, in agreement with the Patriarch of Constantinople, instructed the Governor of Jerusalem by telegraph to protect the clergy, and no longer to recognize Kyrillos as Patriarch. The Greek Government at once deposed the Greek consul, and the Porte forbade all the newspapers to publish any more polemical articles on the question, and ordered the deposed Patriarch to take up his abode in the little island Prinkipo, in the sea of Marmora.

The bishops who had signed the decree of deposition were the Archbishop of Gaza and the Bishops of Lydda, Neapolis (Nablus), Sebasta Tabor, Philadelphia, Jordan, and Tiberias. They then elected the Archbishop of Gaza Patriarch of Jerusalem. The bishops and archimandrites who at first sided with Kyrillos soon deemed it the safest to declare their submission, which they did in the following letter to the Patriarch of Constantinople:

To his Holiness the Ecumenical Patriarch Anthimos, Jerusalem, December 10, [N.S. 22,] 1872.

We, the undersigned, the Metropolitans Agapios of Bethlehem and Niphon of Nazareth, and the Archimandrites Yussuf, Chrysanthos, Joseph, Gregorios, and the Protosyngels Daniel, Gabriel, and the others of our party among the monks of Mar Saba, [a monastery not far from the Dead Sea,] have for a moment sided with the ex-Patriarch, Kyrillos, and have, by our telegram of November 27, [N.S. December 9,] protested against the resolution of the Synod of Jerusalem. But having already repented, we implore the indulgence of the Church and humbly pray for pardon, as we recognize all the resolutions of the Synod of Jerusalem, and turn away from Kyrillos.”

The Russian Government soon gave another proof of its sympathy with Kyrillos and with the Bulgarians by laying embargo upon all the property of the Patriarchate of Jerusalem which is situated within the territory of Russia. The property embraced about thirty estates, situated in the best districts of Bessarabia, and yielding an annual rent of 200,000 rubles. At the same time the Russian ambassador in Constantinople must have interceded in behalf of the deposed Kyrillos with great energy, for the Turkish Government not only set him free after a few weeks, but also asked his pardon for the injury done him.

In Constantinople, in the meanwhile, the Ecumenical Patriarch had in November prevailed upon the Turkish Government to ask the Bulgarian Exarch to make propositions with regard to a change in the clerical dress of the Bulgarian clergy, so as to distinguish them from those in ecclesiastical communion with the Patriarch of Constantinople. The Exarch was afraid that the abandonment of a dress which the mass of the people looked upon as an integral part of the clerical dignity might be injurious to the interests of the Bulgarian Church, and he therefore refused to make the demanded change.

***

Methodist Quarterly Review, April 1874

The Bulgarian Church question has, on the whole, attracted less attention during the year 1873 than in the previous years. The Bulgarians, undoubtedly, have the sympathy of the Slavic Churches of Russia, Austria, Roumania, Servia, and Montenegro; but the Turkish government was again, as usual, very vacillating in its policy. The Bulgarians complained of the partiality of the new Minister of Justice, Midhat Pasha, in favor of the Greeks. When, however, on June 25, the Patriarch of Constantinople, Anthomos [sic], refused to join the other dignitaries of the country in congratulating the Sultan upon the twenty-fifth anniversary of his accession to the throne, because the Turkish government declined to exclude, in accordance with his request, the Bulgarian exarch from the official reception, the Turkish government declared to the Patriarch its decided disapproval of his conduct. In September the Synod of Constantinople expressed to the Patriarch their want of confidence in him, whereupon he resigned his office. In December a new Patriarch of Constantinople was elected in place of the deposed Anthomos. The Turkish government did not exercise her right of striking out one or several names of the ten candidates whom the Electoral Synod had chosen, the Grand Vizier, Raschid Pasha, declaring that all of them were acceptable to the government. The Synod, which consists of priests as well as delegates of the laity, then elected the former patriarch, Joachim II, as Patriarch of Constantinople.

As the immense majority of the members of the Oriental Church of European Turkey are Slavic, the Greeks who prevail in the government of the Church of Constantinople begin to appreciate the necessity of making concessions to them, lest the movement for the establishment of independent Churches on the basis of nationality, which already has emancipated the Churches of Roumania, Serbia, and Bulgaria from the jurisdiction of the Patriarch of Constantinople, become general. The new Patriarch, Joachim, being called upon to appoint a new Metropolitan of the Slavic Churches of Bosnia in January, 1874, has gained the universal approval of Bosnians by appointing to that office Bishop Anthomos, who is an enthusiastic supporter of the national movement among the Slavi of Turkey.