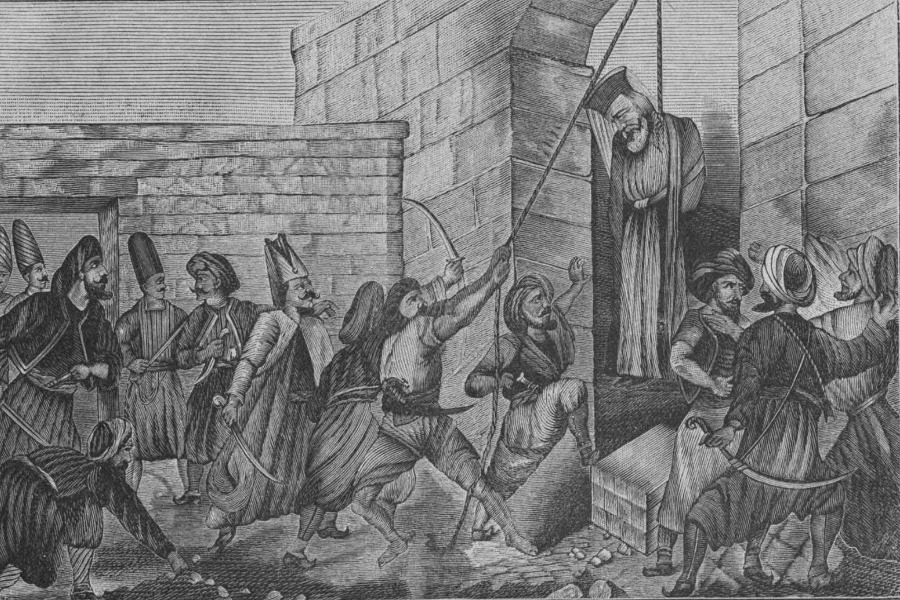

At around five o’clock in the afternoon on Holy Saturday, 1821, Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory was celebrating the Vesperal Divine Liturgy at the Phanar when Ottoman police surrounded and seized Gregory and the other bishops who were concelebrating with him. They dragged the Patriarch, fully vested, to the main gate of the Phanar, where they hanged him. The ascetic Gregory was emaciated from fasting, and his body weighed too little for the hanging to break his neck and kill him instantly, so he hung for a long time, convulsing into the night before he gave up his holy soul. The Sultan had a notice attached to the body, accusing Gregory of having “secretly acted as the leader of the revolution,” referring, of course, to the Greek Revolution that had just begun. This, despite the fact that Gregory had publicly condemned and excommunicated the revolutionaries.

Four more metropolitans were executed at the same time as Patriarch Gregory, in different parts of Constantinople – Dionysius of Ephesus, Athanasius of Nicomedia, Gregory of Derkoi, and Eugenius of Anchialos. The elderly former patriarch Kyrillos was also hanged, as well as two of Patriarch Gregory’s personal aides. The next day – Pascha – amidst turmoil not seen since the fall of Constantinople in 1453, the Holy Synod elected a new Patriarch, the timid Eugenius II, who had to brush past Patriarch Gregory’s hanging body on his way to the Sultan’s palace to have his election confirmed.

Patriarch Gregory’s body was left hanging for three days, after which the Ottoman government ordered four or five Jewish residents of Constantinople to cut down the body. This group then dragged Gregory’s body through the streets, weighed it down, and threw it into the Bosporus. But through the providence of God, the holy relics did not sink. They floated to the surface and were retrieved by a pious Greek who had taken refuge on a Russian ship. The sailors took Patriarch Gregory’s relics to Odessa, in the Russian Empire, where Tsar Alexander had them buried with great honor.

***

The next summer, Patriarch Eugenius died following what was described by the British Ambassador in Constantinople as “a long and painful illness, occasioned by dropsy on the chest.” His 14 months as Patriarch were filled with constant turmoil. Two days later, the Ottoman government issued this directive to the Greek community (note that “Exalted State” means “Sublime Porte” – that is, the Ottoman central government):

We invite you by this letter to nominate a patriarch who will best impose on your community to fulfill the obligations of subjecthood and always serve the Exalted State with loyalty. The nominee should be someone who would never put his community in danger by encouraging sedition and would immediately report the bandits, ill-wishers, and misfits in his community to the Exalted State. You are to submit your decision, and the Exalted State will officially appoint the nominee as your new patriarch.

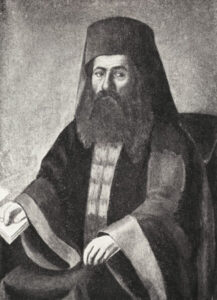

A mixed assembly of clergy and laity immediately gathered and elected Anthimus III, who himself had been imprisoned by the Turks. As one account describes it, “despite the obvious wishes of the clergy, who preferred another, the people clamored for Anthimos so strongly that he won by acclamation.” One candidate, Chrysanthus of Serres, had been born in Macedonia, and a rival, Metropolitan Jeremiah of Derkon rejected Chrysanthus by accusing him of being a Bulgarian: “There is no shortage of Greeks. Why should the Bulgarian become patriarch?” Jeremiah himself would function as the power behind the throne during Anthimus’s patriarchate.

The British Ambassador in Constantinople wrote, “It is satisfactory to observe that in the whole of this transaction, the Ottoman government has acted with so much prudence and propriety, and with such scrupulous attention to the rights and privileges of the Greek National Church.” The Ottomans even went so far as to offer the new Patriarch special honors and treatments which, according to the British Ambassador, had not been shown to any former Patriarch. They also restored the Greeks’ freedom to celebrate feast days, which had been restricted due to fears of large gatherings of Greeks. For his part, Patriarch Anthimus urged his people not to move from Turkey to the territories controlled by the revolutionaries.

At the same time, all that “scrupulous attention to the rights and privileges” of the Patriarchate didn’t include the actual freedom of the Church to choose its Patriarch without Ottoman approval. In the end, the Ottoman state, not the Church, had the final say over who could sit on the Patriarchal throne. This was hardly a new development, but represented the status quo throughout most of the Ottoman period. Patriarchal elections had to be ratified by the Sultan, who also had the power to depose a Patriarch whenever he wished.

***

Patriarch Anthimus lasted just shy of two years, until 1824, when he was deposed by Sultan Mahmud II. According to Dimitrios Stamatopoulos, the apparent cause of Anthimus’s deposition was internal intrigue: Anthimus had refused to allow English Protestant missionaries to use the Patriarchal printing press to publish a translation of the Scriptures in Modern Greek. Other powerful bishops within the Patriarchate disagreed with Anthimus’s position, and they accused him of fomenting an uprising in Serbia. Based on these accusations, the sultan deposed Anthimus and exiled him to a monastery in Cappadocia. Stamatopoulos quotes Manuel Gedeon as describing Anthimus as “a flamboyant man in terms of his physique, but rather buoyant in his spirit; he was devout and god-fearing, and he adored the holy chants and the ecclesiastical liturgies. He was moderately educated, but in his speech he was gentle and sweet. This is why the Christian flock loved him extremely, and they thronged the patriarchal temple during the matutinal and the nocturnal ceremonies, and in Saturday’s vespers, and on every festive occasion; they took great enjoyment in the lengthy chants, through which the choristers sought to please the patriarch and the people.”

On July 9, the Macedonian-born Metropolitan Chrysanthus of Serres was elected to be the next Patriarch. This is the same Chrysanthus who had been rejected two years earlier by Jeremiah of Derkon, who said, “Why should the Bulgarian become patriarch?” Once he became Patriarch, Chrysanthus took revenge by having Jeremiah deposed and confiscating his wealth. Although Jeremiah claimed that Chrysanthus was Bulgarian, the new Patriarch was a member of Filiki Eteria, the Greek revolutionary secret society.

At the end of September 1826, a scandal erupted in Constantinople, where Ecumenical Patriarch Chrysanthus was accused of having an affair with the widow of Asimakis Theodorou, who had been a member of the Filiki Eteria but had betrayed his fellow revolutionaries in 1821. (This earned Asimakis the epithet “double traitor” – he had betrayed both the Ottoman Empire and the Greek revolutionary cause.) On these grounds, Chrysanthus was arrested and imprisoned by the Turks. Eventually, he was allowed to leave prison and live in a monastery, where he died in 1834. He was succeeded as Patriarch by Agathangelos of Chalcedon, who had previously been the Metropolitan of Belgrade.

Agathangelos served as Patriarch for nearly four years, until July 1830, when he was deposed and exiled. He was succeeded by the 60-year-old Archbishop of Sinai, Constantius, who served for four years himself, apparently leaving on his own terms to return to his post as Archbishop of Sinai. (It seems that Constantius had never actually relinquished the Archbishopric of Sinai during his tenure as Ecumenical Patriarch.) The next Patriarch, Constantius II, resigned after just a year on the throne. He was described by a modern historian as “an extremely mediocre and uneducated primate, one of the worst in decades, and his complete inactivity at a time when the Church was so clearly in need of leadership united all factions against him.”

***

From 1821 to 1835, seven men served as Ecumenical Patriarch. One was executed by the Ottoman state, and another died of natural causes. Three were deposed by the Ottoman government, while two (the Constantiuses) resigned, apparently of their own volition (although that’s less clear in the case of Constantius II). During this difficult period, which covers the years of the Greek Revolution and its immediate aftermath, the Ecumenical Patriarchs were at the mercy of the Ottoman government, although this was not really anything new, but rather was basically the norm throughout the Ottoman period

Next time, we will continue to follow the story of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and the Ottoman Empire, beginning with the patriarchate of the remarkable Gregory VI.

Main Sources

Emmanuel G. Chalkiadakis, “Reconsidering the Past: Ecumenical Patriarch Gregory V and the Greek Revolution of 1821,” Synthesis 6:1 (2017), 177-204.

Χαμχούγιας, Χρήστος (2006, Αριστοτέλειο Πανεπιστήμιο Θεσσαλονίκης (ΑΠΘ)), Ο Οικουμενικός Πατριάρχης Κωνσταντινουπόλεως Γρηγόριος ΣΤ’ ο Φουρτουνιάδης εν μέσω εθνικών και εθνοφυλετικών ανταγωνισμών

Charles A. Frazee, The Orthodox Church and Independent Greece 1821-1852 (Cambridge University Press, 1969).

Paschalis M. Kitromilides and Constantinos Tsoukalas, eds., The Greek Revolution: A Critical Dictionary (Cambridge, MA and London: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 2021).

Jack Fairey, “‘Discord and Confusion… under the Pretext of Religion’: European Diplomacy and the Limits of Orthodox Ecclesiastical Authority in the Eastern Mediterranean,” The International History Review 34:1 (March 2012), 19-44.

Jack Fairey, The Great Powers and Orthodox Christendom: The Crisis over the Eastern Church in the Era of the Crimean War (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2015).

H. Sukru Ilicak, ed., “Those Infidel Greeks”: The Greek War of Independence through Ottoman Archival Documents, vol. 1 (Brill, 2021).

Dimitris Livanios, “The Quest for Hellenism: Religion, Nationalism, and Collective Identities in Greece, 1453-1913” in Zacharia, 237-269.

Tom Papademetriou, Render Unto the Sultan: Power, Authority, and the Greek Orthodox Church in the Early Ottoman Centuries (Oxford, 2015).

Theophilus C. Prousis, “British Embassy Reports on the Greek Uprising in 1821-1822: War of Independence or War of Religion?” Archivum Ottomanicum 28 (2011), 171–222.

Dimitrios Stamatopoulos, “Anthimos III of Constantinople” in Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World.

Dimitrios Stamatopoulos, “Orthodox Ecumenicity and the Bulgarian Schism,” in Etudes Balkaniques LI/1: Greece, Bulgaria and European Challenges in the Balkans (Sofia: Institut d’Etudes balkaniques & Centre de Threcologie, 2015), 70-86.

Hi, thanks for your uniquely informative website, which provides a rare unbiased perspective on today’s events. Speaking of Gregory V, you fail to mention that he has been recognised a Saint.

In addition, according to his life at https://holytrinityorthodox.com/htc/ocalendar/los/April/10-05.htm he was in fact a supporter of the revolutionaries. The facts that he publicly denounced them and that he supported them can both be true, but your article only mentions one of these facts.

What is your view on these points?

I’m aware that Patriarch Gregory was later canonized, and I probably should have added a sentence about that. I’m also aware of the theories that he secretly supported the revolution despite his public actions. A deeper dive into his specific story would have to address this.