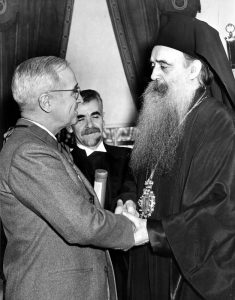

Archbishop Athenagoras awards President Truman the Order of the Holy Sepulcher, including a piece of the True Cross, Feb. 10, 1947

Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras was elected at the end of 1948, thanks in no small part to the intervention of the United States government, in coordination with the governments of Turkey and Greece. Athenagoras was flown to Istanbul in January 1949 aboard a plane provided by U.S. President Harry Truman. Born in Greece, with hierarchical experience on Corfu and in America, Athenagoras was an outsider to the Phanar. He also had a reputation for bucking tradition. Going back to his days on Corfu, he had ruffled feathers in the Church of Greece by introducing the use of organ music in the island’s churches. Putting the edgy Athenagoras at the head of the old school Phanar was like mixing oil and water.

***

In February 1950, Athenagoras had been on the throne for just over a year. During that time, he’d had frequent interactions with U.S. government representatives. The U.S. Vice Consul in Istanbul, James Gustin, was about to return to the United States, and in the weeks leading up to his departure, he had three meetings with the Ecumenical Patriarchate: one with Grand Logothete Ghiokas and two with the Patriarch himself. On February 18, Gustin sent a packet of secret reports on the three conversations back to the U.S. State Department. These reports have since been declassified under the Freedom of Information Act. You can click here to download all three documents.

The first of the three meetings was on February 1, 1950, between Vice Consul Gustin and Patriarch Athenagoras. Upon arriving, Gustin — accompanied by the new U.S. Consul, Merrill — was greeted by the ever-enthusiastic Patriarch, who declared that he “was working steadfastly in America’s cause. He stated that the United States is the hope of the world […] He also expressed appreciation for the close cooperation which he had received in the past from the State Department.” Although this was supposed to be a farewell meeting for Vice Consul Gustin, Athenagoras asked him to come again in a few days, as he wanted Gustin to deliver a letter from the Patriarch to the American government. Gustin promised that he would return.

***

Next, on February 3, Gustin met with Grand Logothete Ghiokas. The Grand Logothete was the ultimate Phanar insider, and his assessment of the Patriarchate in general and Athenagoras in particular represents a rare window into what would normally be a very closed world. Gustin spent three and a half hours with the Grand Logothete, and they talked about all kinds of issues — the status of the Greek Orthodox community in Turkey, the threat of Communism, the election of a new Metropolitan of Derkon, the case of the ousted former Ecumenical Patriarch Maximos.

The elephant in the room was Athenagoras’s deep unpopularity within the Phanar. Grand Logothete Ghiokas characterized the Patriarch as a “non-conformist.” Vice Consul Gustin wrote opened his summary of the meeting by saying, “Mr. Ghiokas took the occasion to reiterate his great concern with the policies of the present Patriarch, previously stated to me in a conversation last August, but which I felt at the time was so damaging to the idea of basic American interests which had prompted the election of Athenagoras that I did not see how a political report could be prepared at that particular time.”

The Grand Logothete repeatedly implored the United States to intervene and “guide Athenagoras into more conservative lines.” This was in American interests, the Logothete said, because the Soviet-backed Moscow Patriarchate was using Athenagoras’s reputation as a “non-conformist” to lobby the other Elder Patriarchates (Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem) for the title of Ecumenical Patriarch to be transferred from Constantinople to Alexandria.

Some of the Logothete’s issues with Athenagoras were very parochial, which is not to say that they were insignificant. He was concerned about new taxes imposed on the Greek Orthodox community by the Turkish government, and the Turks’ recent confiscation of a Byzantine church. Athenagoras recognized these problems but didn’t want to take any direct actions himself, since he feared that this would damage his relationship with the Turkish authorities. According to the Logothete, “The Greek community is well aware of this conciliatory attitude and does not approve of it.”

A few days before Gustin’s meeting with the Grand Logothete, the Metropolitan of Derkon had died. This is a major see in the Patriarchate, and a dispute immediately arose about the successor. The Greek community preferred one candidate (the Metropolitan of Bursa), while the Metropolitan of Imbros and Tenedos lobbied for his own transfer to Derkon, hoping to escape his see, where he was not well-liked by his flock. The Greek government opposed this idea, instead pushing for a reshuffling of several sees in the Patriarchate and the New Lands (canonical territory of Constantinople that, since the Balkan Wars, is part of Greece). According to the U.S. Vice Consul, “The Archbishop of Imbros and Tenedos is keeping on the good side of Athenagoras and of the Turkish government in the hope that he will secure a good personal position for a future Patriarchate election. The Greek government considers him as a traitor, and the inhabitants of the two islands resent his presence there.”

The Grand Logothete then moved on to more general criticisms of Patriarch Athenagoras. Vice Consul Gustin wrote, “As Ghiokas feels that great sacrifices were made in order to bring Athenagoras to Istanbul, all parties concerned must make great sacrifices now to keep him here. He feels that Athenagoras has lost 80% of his support, but it would be a disaster if he were deposed. He feels that the interests of the entire Christian world demand that this man stay here for at least several years and that he be guided to eliminate the persons who are near him and who are motivated only by personal desires; also that Athenagoras be urgently requested to conform to the ancient customs of the position he occupies. Ghiokas feels that this situation has become so urgent through repeated instances of immature, unchurchly, and highly controversial conduct on the part of Athenagoras when appearing in public that it has reached the point that the general interest of Greece, Turkey, and the Western Allies, requires a recommendation by the U.S. to Athenagoras, through such channels as it has, that he become more ‘conformist.'” The Grand Logothete wanted to reign in Athenagoras’s behavior, but not actually to curtail his power. On the contrary, he suggested that the U.S., Greek, and Turkish governments help Athenagoras in “actively drawing in the Patriarchs of Alexandria, Jerusalem and Antioch closer to him by whatever means possible.”

What were Athenagoras’s “immature, unchurchly, and highly controversial” actions, in the eyes of the Grand Logothete? Two of his complaints were “the prospect of a girl choir in the Phanar (a matter coming entirely outside Athenagoras’ jurisdiction as Metropolitan of Constantinople and a matter which is not even within his authority as Patriarch to change so lightly) or the question of moving the throne of St. Chrysostom, which is currently being discussed by Athenagoras.” Perhaps more shocking was an incident that occurred during a Divine Liturgy: Athenagoras “call[ed] up small children to his throne in a local church at the precise moment the officiating priest was celebrating the Sacrament and the rest of the church was engaged in religious contemplation — with Athenagoras then delegating the special prayer of the Patriarch by sentences to the small children who clustered around him.” The Grand Logothete was so disgusted that he walked out of the service. The U.S. Vice Consul commented, “There is an extremely poor public reaction now, and his church community calls him [Athenagoras] an ‘actor.'”

All of this was deeply embarrassing and painful to the Grand Logothete. “Mr. Ghiokas stated that it was a matter of great personal grievance to him that he was forced to confide these matters to an American government official in the hope that the American government would be able to make the suggestion to Athenagoras to govern himself by the ancient rules of the church. Mr. Ghiokas stated that he is finding it impossible to collaborate further with Athenagoras as he does not respect the traditional position of Grand Logothete as one who gives advice to the Patriarch in the strictest confidence. Such advice has upon occasion been repeated to the members of the [Holy] Synod. Ghiokas feels that matters are coming to the point where he must confess his complete inability to work with Athenagoras and must submit his resignation. He states that the Patriarch is always very friendly to him, embraces him, thanks him for his advice, and then usually does the opposite, at the same time not keeping in confidence the matters which he has confided to him.”

***

Five days later, on February 8, Vice Consul Gustin had his final meeting with Athenagoras. The Patriarch asked Gustin to take some notes to deliver to George McGhee, the Assistant U.S. Secretary of State for Near Eastern, South Asian, and African Affairs. The substance of Gustin’s notes is as follows:

(1) Athenagoras told Gustin that the Ecumenical Patriarchate is “strong” against Communism and not in need of financial assistance. He did ask that the American government provide him with two linotype machines (one for Greek and one for English) so that he could publish periodicals.

(2) The Ecumenical Patriarch “expressed grave concern over the Patriarch of Alexandria, stating that Christopher is openly in favor of Russian Communism, and that he is in touch with the Russian church and the Russian government.” Gustin’s report continues, “Athenagoras then stated that he is willing to remove Christopher from his position, provided the Greek government desires to eliminate him.” [Emphasis in original.]

Gustin writes, “I inquired as to the means His Holiness had in mind for effecting this removal, and he said that Christopher was spending a great deal of money to impress certain people, that his Orthodox community in Alexandria is a very important one, and that Christopher, personally, has taken legal steps through a Moslem court in Alexandria to dispossess some of the Orthodox community of their property. He stated that such court action was entirely outside the activities permitted to a Patriarch, and that there were, besides, many other reasons on which he could be removed. I gathered, although it was not so stated, that His Holiness preferred that the [U.S.] Department [of State] approach the Greek government to ask if it desires the removal of Christopher.”

(3) Athenagoras then expressed concerns about Patriarch Alexander of Antioch, “who appears to be under Russian influence, due very naturally to the fact that he received his education in Russia. Athenagoras stated that it would be quite easy for him to influence Alexander as the latter has financial problems (not very great), and a small financial support would bring him completely under Athenagoras’ control. The Patriarch described Alexander as a feeble old man. Antioch also needs the financial support to establish a training school for priests, and to establish a magazine publishing center.”

(4) “The Patriarch said that the Archbishop of Finland needs financial support badly, and that as he has found this Archbishop to be a good man and very obedient to him, he is very anxious that the required financial support be provided for him. The Patriarch added that such support need not be great, and he thought that $5,000 or $10,000 would suffice.” In present-day dollars, that works out to roughly $60,000 to $120,000.

(5) Athenagoras was very positive about the Turkish government, declaring that his own relations with the Turks are “very good.” In contrast to the bleaker picture painted by the Grand Logothete five days earlier, Athenagoras “stressed the complete freedom enjoyed by the Greek minority in Turkey.”

(6) “The Patriarch stated that the Archbishop of Athens is very strong against Communism.”

(7) “Athenagoras then went on to say that the Archbishop of Cyprus [Makarios] is independent, that Athenagoras doesn’t interfere in his political affairs (doubtless referring to the recent Church-inspired plebiscite), but that he knows the head of the Cyprus church to be strong against Communism.”

(8) Speaking of the Patriarch of Jerusalem, Athenagoras said that he was “in very poor health, but very strongly opposed to Communism. His Holiness indicated that he is not worried about the Patriarch of Jerusalem, that although he is weak physically, he is very strong mentally, and there is a very good Locum Tenens with him.”

At the end of his report, Gustin notes, “At one point in the Patriarch’s comments, he stopped to say that he was having a certain amount of difficulty in getting some of his own people (indicating by gesture the walls of his office) to see things his way. He stated that ‘they don’t know that things have changed, and how things are being done these days’. He shrugged to indicate his personal feeling that everything would work out all right in his own organization.” Gustin had just heard the other side of the story from the Grand Logothete, and he was curious to hear more from Athenagoras, but he “did not feel it to be opportune to develop that point.”)

As the two men said their goodbyes, Athenagoras asked Gustin if U.S. Consul General LaVerne Baldwin should also come to visit him at the Phanar. Gustin writes, “I stated that I did not feel that a special call by Mr. Baldwin was really necessary (thinking also that two visits in quick succession by official Americans might arouse too much local comment).”

***

Gustin submitted his report to the State Department, and a couple months later, on April 26, Assistant Secretary McGhee offered his assessment to Consul General Baldwin in Istanbul. (Click here to download it.) “I am inclined to regard criticism of the alleged unorthodox behavior of Athenagoras as largely a reflection of Phanar politics,” McGhee wrote, “and in any case as a problem which is likely to work itself out without any interference on our part.”

McGhee was also not interested in having the U.S. government directly interfere in inter-Orthodox church politics. He said, “I also believe that the Greek Government is competent to make a decision with regard to Patriarch Christopher of Alexandria without our advice and that we should, in general, avoid involvement in the matter of Orthodox appointments and personalities except where it may be necessary to combat direct, obvious and serious Soviet efforts at penetration of the Church.” That said, McGhee was in favor of offering “limited financial help to the Church where it is genuinely needed and likely to be effective,” including getting Athenagoras the linotype machines he asked for, and offering the modest financial aid the Patriarch requested for some of the other Churches.

***

One month after McGhee’s letter to Consul General Baldwin, the Consul General himself called on Athenagoras at the Phanar to say goodbye before his own return to America. I’ve referenced Baldwin’s report before; he writes of the Patriarch, “He stressed his Americanism, belief in the Good Neighbor policy, in democratic methods, and in the courage and frankness of America, which he endeavored to carry out in his policies as Patriarch. He inquired whether we as the American Government felt that he was on the right track in his approach to the Turkish Government and in his treatment of his Patriarchate.” Baldwin, having in mind the Grand Logothete’s complaints, “replied that while numerous petty criticisms had come to my ears originating from conservatives unwilling to admit change, I myself had seen the results of the Patriarch’s energy, moral stamina, and democratic beliefs in the attitude of his own people.” Athenagoras responded “that he did not propose to change his ‘American policy’ regardless of any criticism which might come to him of the character described, and he has the energy to carry through on these lines.”

Eager to be of use to the United States, “Patriarch Athenagoras stated that he would be happy to keep Consul General Lewis advised through present channels of such communications has he might receive which he felt might be of interest to us; I had thanked him for his past actions in that respect.”

***

Two more months went by, and on July 27, the new U.S. Consul General, Charles Lewis, sent another secret report to the State Department — this one with the subject line, “DISSENSION WITHIN THE PATRIARCHATE.”

The memo opens with this sentence: “Chronic dissensions within the Patriarchate have recently come to the surface as a result of various steps taken by Athenagoras to get rid of the opposition against him.” The report describes the protracted battle over filling the vacant see of Derkon: the unpopular Metropolitan Iakovos of Imbros and Tenedos wanted the position and was supported by the Patriarch, while much of the Holy Synod opposed him. Athenagoras was thinking of replacing the formidable Bishop Meliton as the Grand Vicar of the Patriarchate with his new ally Metropolitan Iakovos.

Another key opponent of Athenagoras was the Chrysostomos, the head of the theological seminary at Halki. Athenagoras was attempting to promote Chrysostomos out of the position, sending to him to be a Metropolitan in the New Lands in Greece. The U.S. Consul General writes, “Mgr. Chrysostomos has now refused to comply with the decision of Athenagoras to remove him and has openly revolted against the decision, threatening to take it before the [Holy] Synod. […] Most of the Orthodox community, however, is critical of Mgr. Chrysostomos, who has held the job for almost two decades, for refusing to acknowledge the Patriarch’s order.” For his part, the Patriarch planned to enlist the Turkish government to help remove Chrysostomos, if necessary.

With the Turkish government, Athenagoras had suffered a setback, as he had openly favored the political party that ultimately lost in the recent Turkish elections. Thus he worked especially hard to curry favor with the new government. Consul General Lewis explains, “Although the Orthodox community now understands the necessity of the Patriarch’s intention to cooperate fully with the Government, particularly since the departure of the People’s Party from power, and supports him in his controversy with Mgr. Chrysostomos, there still exists opposition to many of the Patriarch’s reforms which appear contrary to established tradition.”

***

While I don’t know the precise outcome of all of these little dramas, in the end, Athenagoras seems to have gotten his way. On November 28, Consul General Lewis sent a brief report to the State Department, informing them that Bishop Meliton had been promoted out of his position as Grand Vicar and made the Metropolitan of Imbros and Tenedos. His replacement was Athenagoras’s ally Metropolitan Iakovos of Derkon, who himself had been Metropolitan of Imbros and Tenedos only a few months earlier. (In the years to come, Iakovos of Derkon would become the spiritual father and mentor of Iakovos Coucouzis, the future Greek Archbishop of North and South America.)

Athenagoras, of course, remained Ecumenical Patriarch for another two-plus decades, until his death in 1972.

Excellent as always. Thank you. Great documents.

Thank you!