For over a year now, I’ve been telling the story of the Ecumenical Patriarchate in the nineteenth century. Here are the previous articles I wrote on the subject:

- The Ecumenical Patriarchate at the Mercy of the Sultan (1821 to 1835)

- The Patriarch Who Defied the Ottoman Empire (1835 to 1840)

- The Ecumenical Patriarchate on the Eve of War (1840 to 1852)

- Orthodoxy’s Holy War and the Ecumenical Patriarchate (1852 to 1856)

- The Longest Schism in Modern Orthodoxy: Bulgarian Autocephaly and Ethnophyletism (1838 to 1872)

This article picks up the narrative in the 1870s, in the era following the 1872 Council of Constantinople and the emergence of the “Bulgarian Schism.”

***

The later years of the Ottoman Empire were difficult for the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The fortunes and power of the EP were directly linked to the fortunes and power of the Ottomans. As parts of the Ottoman Empire broke away and became independent countries, the Orthodox of those countries inevitably sought their own ecclesiastical independence from the EP, which was viewed as an Ottoman institution. This wasn’t a slur or a slander — the EP very obviously was an Ottoman institution. No Ecumenical Patriarch, or even bishop, could be elected without Ottoman approval, and Orthodox hierarchs functioned as tax farmers on behalf of the Ottoman state, responsible for the taxation and civil government of the Orthodox people in the Empire. So as Ottoman power declined, so too did EP power. The Bulgarian schism was novel in that church independence preceded national independence. The Ottomans gave in to Bulgarian demands in a desperate effort to keep civil control over millions of Bulgarian subjects. If that meant selling out the EP, so be it.

In April 1877, the Russian Empire, in an alliance with Romania, declared war on the Ottoman Empire, beginning the Russo-Turkish War. The next month, Prince Carol and the Romanian Parliament declared Romania’s complete independence from the Ottoman Empire. The prince appealed to the clergy of Romania to support the war. In January 1878, the fighting ended with an armistice, and in March the Ottoman and Russian Empires signed a peace treaty that recognized the independence of Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania, and created a Principality of Bulgaria as an autonomous vassal state of the Ottomans. Romania then declared itself a kingdom and elevated Prince Carol to King.

As the peace treaty was being negotiated, Russian intermediaries approached hierarchs and lay leaders of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, hoping to find a solution to the Bulgarian schism. The Russians proposed an autonomous Bulgarian Exarchate that would acknowledge the authority of the EP and would cede territory in Northern Thrace back to the Phanar. When the government of Greece got wind of the negotiations, it instructed its ambassador in Constantinople to intervene and kill any deal with the Bulgarians. Evangelos Kofos writes, “[T]he Patriarch [Joachim II] lost no time to disclaim any intention to act contrary to public opinion. In tears, he confided to Koundouriotis [the Greek ambassador] that he had no other thought but to serve, as best as possible, the interests of Hellenism.”

***

On August 5, 1878, Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim II died. He was succeeded by the 44-year-old Joachim III, who was viewed by the Greek state as an ally, and by the Turks with suspicion. At the time of the younger Joachim’s election, the Bulgarian primate, Exarch Joseph, was in Bulgaria (rather than his headquarters at Constantinople), and the new Patriarch Joachim took advantage of this by arguing to the Ottoman government that the Exarch should not be allowed to return to Constantinople. Joachim brought up the issue of clerical attire, which had originally been raised after the Council of 1872: he argued that the Bulgarian clergy should be required to dress differently than other Orthodox clergymen, to distinguish “schismatic” from canonical clergy. But the Ottomans, still stinging from their defeat in the Russo-Turkish War, ignored Joachim’s requests.

During the Russo-Turkish War, some Russian army priests in Bulgaria had concelebrated with clergy of the Bulgarian Exarchate. In response, in March 1879, Patriarch Joachim wrote to the Russian Embassy in Constantinople, threatening to take “appropriate steps” to punish the Russian Church, including the possibility of declaring the Russian Church itself to be schismatic.

That October, Joachim opened secret negotiations with the Austro-Hungarian government regarding the status of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Prior to 1879, the church in these regions was under the Ecumenical Patriarchate, but after the Austro-Hungarian Empire occupied the territories, it wanted to transfer them to the jurisdiction of the Serbian Patriarchate of Karlovci. A Russian embassy staffer commented on the negotiations, “The new political situation in Bosnia and Herzegovina will separate them step by step from the Patriarchate of Constantinople. On one hand, one should be cautious because Austrian domination can be favorable for the Catholic propaganda in these regions. On the other hand, anything will help the formation of a Bosnian national church, which will naturally gravitate to the Serbian church.”

***

The years following the Russo-Turkish War were full of challenges for the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Ottoman Empire was losing ground in Europe and the Patriarchate’s territory was shrinking by the decade. The imperial reforms begun in the preceding decades reduced the power of the Patriarchate in the “Rum millet,” leading Patriarch Joachim to write a memorandum to the Ottoman government in November 1879, attempting to defend his Church’s privileges within the Empire: “the privileges of the clergy, churches, monasteries, schools, charities with their real estate, jurisdiction over marriage, divorce, wills, the property of orphans, and the right of prelates to sit in local administrative councils.” Joachim had a personal audience with the Sultan, reiterating this position. In response, the Sultan complained to the British ambassador, hoping that the British might influence the Patriarch to back down.

In 1880, the Ecumenical Patriarchate suffered another blow to its privileges in the Ottoman Empire. A Greek Orthodox Christian named Makarios Minas had died and left his property to charity. His brother, seeking to claim the inheritance for himself, appealed to the Ottoman court rather than to the Patriarchate. In response, the Ottoman Minister of Justice stripped the church hierarchy of its role in adjudicating inheritance disputes involving Orthodox Christians, assigning this task to the Ottoman courts. This was a slap in the face to Patriarch Joachim, who had, just recently, specifically asked that the Sultan allow the Church to retain its jurisdiction over (among other things) wills.

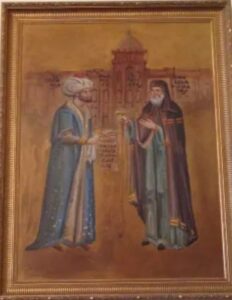

Oil Painting of Mehmet II and Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios, commissioned by Patriarch Joachim III and installed at the Great School of the Nation in Constantinople.

In June, Joachim corresponded with his spiritual son, the Ottoman ambassador in London (who was Greek Orthodox). The ambassador sent Joachim a picture he had found in a book, depicting Mehmet the Conqueror and Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios. Joachim asked the ambassador to obtain a copy of this picture as an oil painting. The resulting image, which shows Mehmet handing Gennadios a document symbolizing the privileges of the Patriarchate, would be hung in the Great School of the Nation (constructed in 1882) and would form the basis for a famous mosaic installed at the Phanar in the 1980s.

***

In June 1881, the Ottoman government began to restrict the freedoms of the Orthodox press and educational system, which had been controlled by the Ecumenical Patriarchate. The Ottomans found the editor of the patriarchal newspaper, Ecclesiastiki Alitheia, to be politically unreliable, and the Minister of Education demanded an explanation from the Patriarch for content in the Greek Orthodox school textbooks, which now had to be approved by an Ottoman censure committee. The Ottomans went on to appoint a government inspector for Orthodox schools, further reducing the independence of church institutions.

The power of the Patriarchate continued to erode in 1882. In March, the Romanian Parliament proposed that the Romanian Church be elevated to the status of a patriarchate. A few weeks later, on Holy Thursday, which was also Annunciation that year, the hierarchs of Romania blessed new Holy Chrism for the first time in Romanian history. This provoked an angry response from Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim III in July, to which the Holy Synod of Romania responded that it had just as much a right to consecrate its own Holy Chrism as Russia did. Lucian Leustean writes of this, “Thus, after the military victory against Ottoman rule, the church proclaimed its spiritual victory against Constantinople.”

In May, the dioceses of Thessaly, Arta, and part of Ioannina were transferred from the Ecumenical Patriarchate to the Church of Greece. Over the summer, Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim corresponded with the Greek ambassador in Constantinople, expressing his fears of a Russian “conquest” of Mount Athos, and his concerns about the financial situation of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which was in dire straits, forced to beg for help from “Orthodox governments” – particularly Russia. Joachim told the Greek ambassador, “I am ruined unless you regularly help me.”

But a bit of consolation came in September, when the new facilities of the Great School of the Nation were opened in Constantinople, complete with the new oil painting of Mehmet the Conqueror and Gennadios Scholarios.

***

In October 1882 and February 1883, the Ottomans issued the traditional berats to two newly appointed metropolitans of the Ecumenical Patriarchate. These berats featured an explosive new provision: the metropolitans would be judged by Ottoman courts, not Patriarchal courts. Patriarch Joachim protested this latest violation of the rights of the Patriarchate. Lora Gerd writes, “The patriarch pointed out all the areas in which the rights of the Christians had been violated: hereditary law, the right to free construction of church buildings, schools, and charity institutions, administration of schools and punishment of clerics.” The Russian ambassador to the Ottoman Empire supported Joachim, filing an official protest with the government, and the Russian foreign minister warned the Turks to stop their measures against the Ecumenical Patriarchate lest the peaceful relations between the Ottoman Empire and Russia be disrupted. Initially, these protests seemed to have their intended effect, as Patriarch Joachim was issued a berat that respected the traditional privileges of the Patriarch. The Ottoman Grand Vizier fired back that Joachim should be content with the same kind of limited role that Orthodox clergy had in Greece.

In March, Joachim entered into a concordat with the Austro-Hungarian Empire resolving the status of the Serbian Orthodox Church in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Under the agreement, Bosnia and Herzegovina would basically become autonomous: the metropolitans of these sees would be appointed by the (Roman Catholic) Austro-Hungarian Emperor, subject to final approval by the Ecumenical Patriarch. Austria-Hungary paid a lump sum to the Patriarchate to compensate it for its loss of tax revenue from these territories. The Ecumenical Patriarch would still be commemorated liturgically, and Constantinople would continue to provide Holy Chrism. As Lora Gerd writes, “Joachim signed it without enthusiasm. Afraid of the Synod’s indignation, the patriarch presented it as a fait accompli and did not allow discussion of it. He was bitterly criticized for agreeing to the terms in both the Greek and Russian press.”

In July and then again in September, Ecumenical Patriarch Joachim sent two memos to the Ottoman Ministry of Justice, threatening to resign unless the government issued a new berat recognizing all the privileges held by Joachim’s predecessor as Patriarch. These protests achieved nothing. In November, Joachim seriously considered staging a mass resignation, with the Patriarch, the Holy Synod, and the Mixed Council all stepping down in protest of the violation of the Patriarchate’s privileges. In the end, the Patriarch realized that this would do more harm than good. He also realized that pushing too hard on the ancient privileges of the Patriarchate, granted by Mehmet the Conqueror, would likely backfire, since, as Denis Vovchenko explains, “it would reveal the substantial changes in the status of the patriarchate since 1453.” Instead, Joachim focused on more recent documents – the license provided to Patriarch Joachim II and the “Community Regulations” given to the Greek Orthodox community. Joachim wrote, “They contain everything we have and mean when referring to privileges.”

Joachim asked the Sultan for an audience for himself and the Holy Synod, but the Sultan refused. A few days after this rejection, Joachim tendered his resignation as Patriarch, although this seems not to have been accepted, and was, apparently, not really a serious offer by Joachim, who was desperately trying to apply whatever pressure he could on the government.

In March 1884, the Ottoman government issued a decree that any clergyman or monastic convicted of a crime would be held in the state prison system rather than a church prison. This was the last straw for Patriarch Joachim — he clearly could not prevent the Ottomans from continuing to disregard the privileges of the Patriarchate in the Empire. This time, the government accepted his resignation. Joachim was succeeded by the 47-year-old Joachim IV (who was the nephew of the late Patriarch Joachim II).

***

Joachim IV lasted just two and a half years — in November 1886, aged just 49, he resigned due to ill health. He died three months later. Joachim III was one of the two leading candidates to replace him, but he lost the election 12 to 5, with Dionysius of Adrianople becoming the new Patriarch in January 1887. That fall, the Ottoman government demanded that the Ecumenical Patriarchate present documentation of its real estate holdings. In most cases, formal documents did not exist, leading the Ottomans to threaten the Patriarchate with confiscation of these properties.

In February 1888, a Greek teacher from Macedonia was arrested for revolutionary activity. The Turks discovered that the teacher had corresponded with a metropolitan, Cyril, who was summoned to the Porte to be interrogated. Metropolitan Cyril refused, since Orthodox bishops were always tried in ecclesiastical courts. The Holy Synod of Constantinople blessed Cyril to meet with Ottoman officials as long as the meeting was not an “interrogation.” The Turks then arrested the protosyngellos of Metropolitan Cyril, and Patriarch Dionysius formally protested to the government. It was to no avail, and soon after this, the Ottomans dismissed another bishop, Metropolitan Lukas of Serres, from his see. This episode was one in a long string of actions by the Ottoman government showing disregard for the Patriarchate’s freedom and privileges. In all of this, the Phanar chose not to approach the Russians for help.

The same year, the Ottoman government declared that patriarchal court decisions had no validity; the church court would only be allowed to serve as a mediator in disputes, without the power to render a final judgment. Along with these reduced powers came a reduction in income, since the church courts could no longer charge fees, and, to make matters worse, the government then banned the Patriarchate from issuing fundraising encyclicals.

***

The government continued its attacks on the freedoms and privileges of the Patriarchate in 1889. The Ottomans had already banned the Patriarchate from taking any official decisions on judicial matters and limited its fundraising ability. This time, the government “raised the issue of state salaries for clergy and, more ominously, limited the participation of Christian members on local courts to two months a year.” Patriarch Dionysius formally protested to the Grand Vizier, but to no avail, leading the Patriarch, who up to this point had resisted the urge to ask for Russian assistance, to send an emissary to meet with the Russian diplomats in Constantinople. The Russians promised their support, including offering financial aid to help offset the Patriarchate’s declining revenues. Thanks to Russian diplomatic intervention, in September, the Patriarchate scored a rare victory, securing control of its monastic property.

In July 1890, apparently in response to pressure from British and Austrian diplomats in favor of Bulgaria, the Sultan authorized the creation of two Bulgarian Exarchist sees, Ochrid and Skopje, with Bulgarian bishops residing in the same cities as existing Greek bishops under Constantinople. Denis Vovchenko writes, “This move not only scandalized and divided local Orthodox Christians but also strengthened the influence of Prince Ferdinand of Bulgaria.” Adding insult to injury, the Ottomans further eroded the Patriarchate’s judicial authority, leading the Russian diplomats in Constantinople to fear that Orthodox Christians would come to be judged based on Sharia law.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate held an extraordinary meeting of the Holy Synod and Mixed Council, and the decision was made that Patriarch Dionysius should resign in protest, and that all churches throughout the Patriarchate should be closed. Dionysius submitted his resignation twice, on July 23 and again on August 2, but both times the government refused to accept it. Russian diplomats mobilized in support of the Patriarchate – rumors spread that the heir to the Russian throne, the future Tsar Nicholas II, would soon be visiting Constantinople, and the Russian envoys warned the Ottomans that Nicholas would embarrass the Sultan if the Orthodox Church was not accorded proper respect. Although Nicholas never did visit the Ottoman capital, the threat of a major public slight by the more powerful Russian Empire was a serious one for the Sultan.

On October 4, the Patriarchate declared the Church to be in a state of persecution and proclaimed an interdict from October 4 to December 25 (Julian), with all Divine Liturgies banned. This, of course, included Christmas Day, and the Orthodox faithful became increasingly agitated at the prospect of a year without Christmas, to the point that the Porte feared an insurrection. When Sultan Abdulhamid threatened to punish the bishops, Metropolitan Germanos of Heraclea, one of the leading hierarchs of the Patriarchate (and a future Patriarch himself) reportedly dared the Sultan, bringing him a rope and saying, “Your Majesty knows that the patriarchate has more gates than one, on which a lot of Archbishops can be put to death in the same way as Patriarch Gregory V.” Tsar Alexander III intervened, threatening war if the privileges of the Ecumenical Patriarchate were not respected. Facing threats from without and within, the Ottomans finally yielded and announced on Christmas Eve that the Phanar’s privileges would be respected.

The government’s Christmas Eve capitulation notwithstanding, the “question of privileges” of the Ecumenical Patriarchate persisted into 1891. In negotiations with the government, the Phanar made numerous key concessions: criminal cases involving clergy would now be tried in Ottoman, not ecclesiastical, courts; while convicted clergymen would be imprisoned in church prisons as before, while their trial was pending they would be held in a special section of Ottoman prisons; Ottoman courts would fix the amount of alimony in cases of divorce; and, with the consent of the bishop, Ottoman officials could inspect Greek Orthodox schools.

In August, Patriarch Dionysius died at the age of 71. During the 48 hours following his death, the Patriarch’s body lay – or, rather, sat – in state at the Phanar. A New York Times correspondent describes the scene:

He sat on a throne covered with black velvet and silver tissues. His corpse was arrayed in the gorgeous pontifical vestments glittering from throat to hem with precious jewels. On his head was placed the pontifical crown, all ablaze with huge diamonds, emeralds, and rubies. His glazed eyes were wide open and gazed with the stony stare of death straight down the marble-columned nave of the church. His left hand clasped a gold-bound volume of the Gospels, and his right was upraised as if for benediction. Two black-robed priests muttered prayers, kneeling on each side of him, and now and again Greeks and Armenians approached the dead Pontiff and, making low obeisance, kissed his icy fingers or the edge of his vestments.

Patriarch Dionysius was buried the next day with great pomp. He was honored by the Ottoman authorities, and out of respect the Sultan cancelled the Imperial Regatta that was scheduled to be held that day.

Although some hoped that Joachim III would return to the throne, in the end, after two months of internal squabbling, the Holy Synod elected a surprise compromise candidate, Metropolitan Neophytos of Nikopolis, who became Patriarch Neophytos VIII.

***

For the next few years, things were relatively quiet, which makes this a reasonable place to pause our story. Decades earlier, Tsar Nicholas I declared the Ottoman Empire to be the “sick man of Europe,” and as Ottoman power declined and its territory was chipped away from it, the Ecumenical Patriarchate also saw a steady reduction in its own power. It’s not surprising that the EP’s territory would shrink along with the Empire’s, but adding insult to injury, the Ottomans took aim at the internal rights and powers of the EP within the Empire. Where once the church hierarchy had reigned rather supreme over the Orthodox of the Empire (not just religiously but legally), now it found itself stripped of more and more of its legal privileges, more and more limited to religious functions only.

It’s also notable that the term “privileges,” in this era, was used specifically to refer to the legal rights of the EP in the Ottoman Empire. As Joachim III put it, the documents granted by the Sultan “contain everything we have and mean when referring to privileges.” Today, the Phanar uses “privileges” in an ecclesiastical sense, referring to its canonical rights and prerogatives.

The 1870s-1890s might have felt like a dark period for the Ecumenical Patriarchate, but it was just a prelude of what was to come.

Main Sources

G. Georgiades Arnakis, “The Greek Church of the Constantinople and the Ottoman Empire” The Journal of Modern History 24:3 (Sept. 1952), 235-250.

Anton Bertram, “The Orthodox Privileges of Turkey, with Special Reference to Wills and Successions,” Journal of the Society of Comparative Legislation 10:1 (1909), 137-140.

Adrian Fortescue, The Orthodox Eastern Church, 2nd ed. (London: Catholic Truth Society, 1908).

Lora Gerd, Russian Policy in the Orthodox East: The Patriarchate of Constantinople (1878-1914) (De Gruyter Open, 2014).

Evangelos Kofos, “Attempts at Mending the Greek-Bulgarian Ecclesiastical Schism (1875-1902),” Balkan Studies 25 (1984), 347-375.

Evangelos Kofos, “Patriarch Joachim III (1878-1884) and the Irredentist Policy of the Greek State,” Journal of Modern Greek Studies 4:2 (October 1986), 107-120.

Ivan Ivanovich Sokoloff, “The Orthodox Church of Constantinople,” The Constructive Quarterly 4:1 (March 1916), 1-29.

Denis Vovchenko, “A Triumph of Orthodoxy in the Age of Nationalism: The Ecumenical Patriarchate, the Sublime Porte, Russia, and Greece (1856-1890),” Modern Greek Studies Yearbook volume 28/29 (2012/13), 255-266.

Pantelis Touloumakos, “Dionysios V of Constantinople,” Encyclopaedia of the Hellenic World, Asia Minor.

“Dionysius V. Laid Away,” New York Times, November 15, 1891, 20.

Great post, as usual. Do you know when the pledge to defend the privileges of the Ecumenical Patriarchate was incorporated alongside the traditional pledges of the bishop at his ordination? If not, that may be something worth looking into.

I’ve been wondering about that myself. The same pledge is used in other churches, e.g. Antioch, although I suspect they copied it from Constantinople.

That’s interesting. I didn’t know anyone else used such a thing. The incorporation of pledges unique to historical circumstances isn’t totally unique: after the Palamite councils, newly-ordained bishops were made to take oaths to uphold Palamite orthodoxy; and, during the Unia, there were oaths of fidelity to the Orthodox hierarchy.

But those both carry a certain dogmatic weight. The incorporation of the pledge to uphold the privileges of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, following the pledges to teach Orthodoxy and uphold the sacred canons, seems to suggest an elevation of these “privileges” to an element of faith. This is precisely what certain detractors of the modern Ecumenical Patriarchate claim: these are no longer simple procedural or territorial disputes, but something more serious.

Hello, great article. Do you know if Joachim IV had a sister and if yes, what her name would be? Thanks so much!

I don’t know.