The Greek term typically translated as “Church” in the English New Testament (ekklesia, which can also mean “assembly”) is used throughout the Greek Old Testament to refer to the gathering together of the people of Israel. Its meaning is the same as in the New Testament—the Church is the assembly of Israel, God’s people, which has been renewed and restored. The tribes formerly lost have been reconstituted from among the nations into which they were dispersed. The notion that the Church has “replaced” Israel or is somehow a “new Israel” is nonsensical once one understands the language the Scriptures speak. The Church is Israel. Specifically, the Church is the assembly of Israel, God’s people, set apart to offer worship, praise, and sacrifice to Him. It is not that God’s people have ceased to be an ethnic group or nation, but rather that they were never an ethnic entity, and only ever so briefly a national one.

Fr Stephen De Young, Religion of the Apostles, 214-15.

The term “church” has taken on a variety of meanings: it can mean the local assembly, the building in which the assembly gathers, or the broader network of local assemblies in a region or even globally. But “church” is often used in another way, to refer not to the assembly – the ekklesia – itself, but to a governing structure of that ekklesia (such as a patriarchate).

This is a misnomer. The governing structure of a church is not the church itself. The system of the twelve tribes in the Old Testament, for example: the priests and/or the elders of the people were not, by themselves, the ekklesia of Israel. And the tribal system itself was not essential to the existence of Israel, since it no longer exists, yet Israel — the Orthodox Church — lives on. Likewise, it’s wrong to identify a particular governing structure (e.g., the Moscow Patriarchate) as being identical with the church that that structure governs (the Russian Orthodox Church).

***

In the first century, as Israel was transformed by the coming of Christ and the descent of the Holy Spirit, local communities formed, structured in the same basic way that Israel had long been structured: a high priest (the bishop), surrounded by the elders (presbyters), deacons (equivalent to Levites), and the rest of the people of God. In each locality – in each city or town – the local ekklesia constituted the fulness of the people of God in that place, while remaining connected to all the other ekklesiae throughout the world via a network of interdependence. For example, when a local church needed a new bishop, the community would nominate a worthy man, who would be ordained by all of the bishops from the neighboring churches. (The canonical requirement for three bishops to ordain a new bishop is actually a bare minimum; the normative standard was that every neighboring bishop would participate.)

The Apostles themselves established the practice of meeting in council to address issues that affected the entire ekklesia throughout the world. This is recorded in Acts 15. The model of this Apostolic Council was copied everywhere. When major issues arose, all the bishops of the region would gather together in council (or synod) to discern the will of the Holy Spirit. In time, with lots of common issues cropping up frequently, the bishops of various regions began to convene at regular intervals, creating standing synods of bishops. These would naturally be held in major cities, and the bishops of these major metropolitan areas eventually became known as “metropolitans.” Because of the importance of the metropolitan city, the bishop of that city would serve as chair of the regional synod of bishops – first among equals. The nature of the relationship between the metropolitan and his synod is reflected in Apostolic Canon 34.

The term “diocese” was not originally an ecclesiastical word; it was actually an administrative division of the Roman civil government established under the Emperor Diocletian. The Church embraced this framework and structured its administration to line up with these Roman civil administrative divisions. Our canons basically assume the existence of dioceses, which makes sense because our canons were mostly drafted in the Roman Empire in an era when these units were the norm.

There were two Apostolic usages of ekklesia – the local and the universal – but with the emergence of standing synods and metropolitan and diocesan structures, a third usage emerged: ekklesia to mean the network of local ekklesiae under bishops who sit on a common synod. Nowadays, when we say “the Church of Constantinople” or “the Church of Alexandria” or “the Church of Antioch,” we almost never mean merely the local community of Orthodox Christians in the cities of Istanbul, Turkey; Antakya, Turkey; or Alexandria, Egypt. Instead, these terms refer to the broader network of ekklesiae under the respective synods of bishops chaired by the bishops of Constantinople, Alexandria, and Antioch. It’s important to note that this usage is not Apostolic. It’s not present in Scripture or in the early centuries of the Church. It’s a later administrative concept, not a fundamental ecclesiological principle.

So on the one hand, we have these core, unchangeable principles: the universal ekklesia, the local ekklesia led by the bishop, and the gathering of bishops in council to address common issues. These are part of the faith which was once delivered unto the saints (Jude 1:3). On the other hand, we have those principles manifested in history: the emergence of metropolitan sees, standing synods of bishops, dioceses that mirrored the civil divisions, and networks of churches under standing synods that came to be known as an ekklesia. This shouldn’t be a surprise, since the Church is an eternal and unchanging Body that simultaneously exists in various times and places, baptizing what is redeemable in those times and places. I’m not saying that our governing structures and administrative concepts are illegitimate; I’m saying, they are not Apostolic, they are not essential to the Church, and they are, and always have been, subject to change.

***

At the time of the Apostles, Antioch was one of the three great cities of the Roman Empire, along with Rome and Alexandria. It was a major center for Judeans outside of Jerusalem itself, and many of its residents became followers of Christ in the early days after Pentecost. The city was, famously, the place where the term “Christian” was first used. The ekklesia of Antioch counted among its founders the great Apostles Peter and Paul, and one of its first bishops, St Ignatius, is the church father who most clearly articulated the Apostolic ecclesiology.

Because of both Antioch’s position in the Roman Empire and the Apostolic origins of the Antiochian church, the bishop of Antioch soon emerged as one of the leading hierarchs in the church worldwide. Even so, if you go read early histories of the Church (for example, Eusebius), you’ll never find a reference to the “church of Antioch” that means something other than the ekklesia of the city of Antioch itself. The same goes for every other reference to “church of [insert city]” – the “church of Rome” is not the entire so-called “Western Church” (a concept that did not exist in the early centuries), but rather the literally local ekklesia in the city of Rome.

During the age of the Ecumenical Councils, the bishops of Rome, Alexandria, and Antioch – and soon, of Constantinople and Jerusalem as well – were granted broader regional administrative authority. Later, in the sixth century, the title “patriarch” was given to the bishops of these cities. Notably, “patriarch” was not used in this way prior to the mid-to-late sixth century. About that – in the early ninth century, St Theophanes the Confessor wrote a wonderful year-by-year history, from the third century up to his own day. By the time Theophanes lived, the term “patriarch” was firmly entrenched as a technical word referring to those five bishops (the “pentarchy”). And it seems that Theophanes didn’t realize that it hadn’t always been this way. Writing of events in the early sixth century – that is, before “patriarch” came to have its later meaning – he says, “Theodore the historian senselessly calls the bishop of Thessalonica a patriarch.” Sure, it would have been senseless to say that in Theophanes’s day, or in ours – but in the era before St Justinian the Great was emperor, it wasn’t senseless at all.

Just to finish the thread about Antioch – in the seventh century, the city and the surrounding region fell to Arab Muslim invaders, and the bishop of Antioch was forced into exile, moving to Constantinople for 60-70 years. The local ekklesia of the city remained, but its governing structure was exiled. At the turn of the twelfth century, the Crusader armies swept in, forcing the Patriarchs of both Antioch and Jerusalem out and replacing them with Latin bishops. As before, the people of the ekklesia of Antioch continued to live and worship in the city, but the status of their governing structure was uncertain. After a few years, patriarchates-in-exile were established, with both the Antiochian and Jerusalem patriarchs living in Constantinople and never setting foot in their sees. In fact, as best I can tell, the last time the Patriarch of Antioch lived in the city of Antioch was around 1100.

In 1268, the Mamluks completely destroyed the city, massacring thousands. From this point until the Ottoman conquest of the region in 1516, there was, for all intents and purposes, no functioning city of Antioch at all. The Patriarchs of Antioch initially were wanderers, living in various places. Yet the overarching structure of the patriarchate continued to exist – there was still a Holy Synod composed of local bishops and they still had a patriarch at their head. In 1364-65, the Holy Synod elected the bishop of Damascus as Patriarch of Antioch. Rather than give up his previous see, the new Patriarch merged the sees of Antioch and Damascus. This is still the case, with the Patriarch of Antioch living permanently in Damascus.

Yet there remained – at least until the devastating earthquakes in February – a literal ekklesia of Antioch (that is, Antakya), which was, until its recent destruction, a modest city in what is now southern Turkey.

Today, when we say “Church of Antioch,” we mean “all of the ekklesiae that are under the ultimate authority of the Holy Synod that is chaired by the bishop who holds the title ‘Patriarch of Antioch.’” Sometimes, we’ll say that the “Church of Antioch” did such-and-such, but what we actually mean is that the Patriarchate or Holy Synod did it, not the ekklesia – the entire Body – itself.

We could do much the same exercise with Alexandria and Jerusalem, too. But let’s skip over those sees and talk about Constantinople.

***

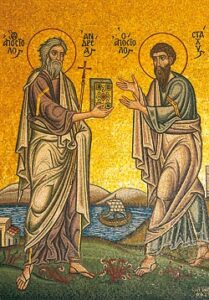

According to tradition, the Apostle Andrew organized an ekklesia in the Roman town of Byzantium and put it under the leadership of its first bishop, St Stachys. This ekklesia – this assembly of the people of God in that particular locality – has continued to exist up to the present day. At the top, however, its governing structure has changed in enormous ways. As the system of metropolitans and standing synods developed, the bishop of Byzantium came to be part of a synod that was chaired by the bishop of Heraclea, who became known as a “metropolitan.” At this point, Heraclea was the big city in the area, so all of this made sense.

In 330, St Constantine established Byzantium as the new capital of the Roman Empire, transforming the town into the great city of Constantinople. Its bishop remained the bishop, and initially, Heraclea remained the local metropolitan see. By the Second Ecumenical Council, it was clear that this made no sense: Constantinople was now the center of the Roman world, quite obviously surpassing nearby Heraclea. So the bishop of Constantinople was given greater administrative responsibility, put on the same level as the bishop of Rome. Canon 28 of the Fourth Ecumenical Council further implemented this new status, and it even explained its own existence: the text of the canon itself explicitly says that because the city is now the capital, home to the emperor and the senate, it is appropriate that its bishop have responsibilities equal to those of the bishop of Rome (that is, the old capital city). This was a pragmatic administrative measure, very much rooted in a specific time and place.

The size of the ekklesia of Constantinople (formerly Byzantium) had grown by a lot, but the ekklesia itself still existed, with its bishop. The change is not ontological but administrative: now, for very practical reasons, tied to changes that had taken place in the Roman Empire, the bishop of the city now supplanted the metropolitan of Heraclea and was given special administrative duties.

In this period, that other concept of ekklesia took root – the network of ekklesiae under a particular synod of bishops. So we can now speak of two “churches of Constantinople,” one in a specific locality and one in a region centered on that locality.

From the fourth through the ninth centuries, the global Church, and the church of Constantinople specifically, was rocked by a string of crises and heresies. From 339 to 843 – a span of 504 years – the bishop of Constantinople was a heretic for 202 years. In other words, the governing structure of the ekklesia of Constantinople was under heretical control 40% of the time. Does this mean that the church of Constantinople was heretical, or ceased to be Orthodox, or even ceased to exist? Certainly not. God preserved his Church, even if, for long stretches of time, the men who controlled the institution of the Patriarchate of Constantinople were heretics. It’s even possible to say that, during these years, the institution of the Patriarchate ceased to control the actual ekklesia of Constantinople. But the church of Constantinople did not fall, regardless of the failings of the Patriarchate at certain points in its history. And each time that Patriarchate fell, it was eventually recovered by the Orthodox.

The conquest of Constantinople by the Latin Crusaders in 1204 ushered in a new era of ambiguity. The Roman elites, including the Patriarch, fled the city, but the ordinary people and parish clergy remained, under the oversight of Latin bishops. The Orthodox Patriarch lived in Bulgaria but died two years later; the imperial succession was claimed by several successor states (Nicaea, Epiros, Trebizond). In 1208, the imperial claimant at Nicaea, Theodore Lascaris, organized a council of most of the bishops of Asia Minor (that is, the bishops of the broader “church of Constantinople”) to elect a new Patriarch, which they did. But it wasn’t until about 1230 that this institution was recognized by all as the rightful patriarchate – in the meantime, the other successor states had their own preferred church administrations. The early thirteenth century thus represents a time of ambiguity both in terms of the identity of the ekklesia of the city of Constantinople and the status of the governing structure of the church of Constantinople (either the local one, or the broader one).

In the mid-fifteenth century, the Patriarchate of Constantinople entered into union with the Pope of Rome. For several years, right up until the fall of Constantinople to the Turks in 1453, the governing structure of the ekklesia of Constantinople was not, in fact, Orthodox. No Orthodox Divine Liturgy was celebrated in the Hagia Sophia. The clergy and faithful who rejected the union and remained Orthodox were, it would seem, a church without a bishop and without a Holy Synod.

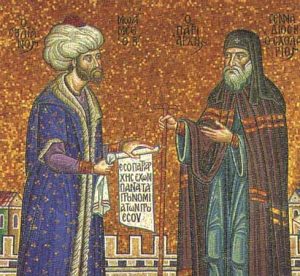

Ottoman Emperor Mehmet II and Patriarch Gennadios of Constantinople. This mosaic was created for the Phanar in the 1980s to go alongside the mosaic of the Apostle Andrew and Stachys.

After Mehmet the Conqueror captured the imperial city in 1453, he authorized the establishment of a new Patriarchate of Constantinople. Here, there is a pretty clean break between the earlier institution – the Patriarchate that had betrayed Orthodoxy – and the new institution that was led by the solidly Orthodox Patriarch Gennadios Scholarios. Many of the Orthodox faithful of Constantinople had died or fled at the time of the conquest, so Mehmet brought in more Greeks from other places to repopulate the city. Whatever the ekklesia of the city was before Mehmet, it was fundamentally different after him. Yet we can certainly see a through-line in terms of the local community founded by St Andrew so long before. The overarching governing structure may have been entirely new, but the ekklesia itself was not.

Perhaps an even bigger shift took place in the 1920s. The Ottoman Empire fell and the secular Turkish Republic rose up in its place. As had happened in 1453, in the 1920s a new Patriarchate was established, breaking from the old Ottoman-era institution. A small minority of metropolitans elected Meletios Metaxakis as Patriarch in late 1921, but he lasted barely a year and a half before being forced out by the new Turkish overlords, who imposed a rule that only a select few bishops would be eligible to serve on the Holy Synod, as patriarchal electors, or as the Patriarch himself. At the same time, the Treaty of Lausanne, which ended the war between Greece and Turkey, called for the mass deportation of almost all of the Greek Orthodox population of Turkey. A mere hundred thousand or so were exempted from deportation, all of them residents of the city of Constantinople. Suddenly, that broader concept of the “church of Constantinople” was at risk of vanishing altogether. The local ekklesia of the city itself would remain, but the network of ekklesiae under the Holy Synod of Constantinople was abolished.

But as this was happening, the Patriarchate expanded the definition of the “church of Constantinople”: The Patriarchate began claiming jurisdiction over all areas outside of the defined canonical territory of another autocephalous church structure – the so-called “barbarian lands.” Thus today, the “church of Constantinople” encompasses ekklesiae around the world. (Constantinople wasn’t alone in establishing “diaspora” jurisdictions; it’s just the only governing structure to claim exclusive authority over the so-called diaspora.)

***

The Russian Orthodox Church is a great example of the difference between a church and the governing structure of that church. According to tradition, the Apostle Andrew first brought Christianity to the land that would become known as Rus’. That said, it wasn’t until the tenth century that the Church arrived in the region at any kind of scale. Famously, St Vladimir, the Grand Prince of Kiev, invited missionaries from Constantinople to evangelize his people in 988. This became known as the Baptism of Rus’ and is the origin point for the Orthodox churches in modern-day Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus. Of course, here I am using the term “church” to refer not to a local ekklesia but to the broader network concept that had, by this point, already fully established itself in the Orthodox world.

(A brief note, because now I have to do this sort of thing: In spelling those words “Vladimir” and “Kiev” and not “Volodymyr” and “Kyiv,” I realize that I may be considered by some to be pro-Russian and anti-Ukrainian, or something. I promise you, that’s not what I am doing. I am simply using the spellings that were, until a year or so ago, the normal, mainstream ways that most English writers would spell those words.)

The original governing structure of the new ekklesia was as a metropolis under the Ecumenical Patriarchate – the Metropolis of Kiev. By the thirteenth century, the city of Kiev had declined, and its status as the leading city of Rus’ was ultimately overtaken by Moscow, although the metropolitan in Moscow initially continued to use the old title “of Kiev.” (For years, there were actually two metropolitans who claimed the title “of Kiev,” both under Constantinople. But that’s a story unto itself.)

Things changed in the 15th century, when most of the bishops of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, including the Constantinople-appointed Metropolitan Isidore of Kiev, entered into union with the Roman Catholic Church at the Council of Florence. When Isidore returned to Kiev, his people rejected him and he fled to the West (eventually becoming the Latin Patriarch of Constantinople, under Rome). In 1448, the Russian bishops then elevated one of their own, Jonah, to become their new primate. This was done without the consent of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which at the time had abandoned Orthodoxy in favor of the Unia. The elevation of Jonah to the rank of Metropolitan is viewed by the Russian Church as the moment of its autocephaly. The Patriarchate of Constantinople returned to Orthodoxy at the time of the Ottoman conquest in 1453, but the governing structure based in Moscow remained independent. In 1589, the Patriarchate of Constantinople finally accepted this new reality, not only recognizing Moscow as autocephalous, but elevating its primate to the status of Patriarch. By 1591, this had been ratified by the patriarchates of Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem.

The new Patriarchate of Moscow lasted for just over a century. In 1700, the Patriarch died, and Tsar Peter the Great refused to allow the election of a successor. The Patriarchate was led by a locum tenens until 1721, when the Tsar formally abolished it and replaced it with an entirely new structure: a Holy Synod coordinated by a lay government official known as the “chief procurator.” This framework was modeled on the arrangements of the Lutheran Church in Sweden and Prussia. The new Synodal system lasted for nearly two centuries – quite a bit longer than the original Patriarchate – until the fall of the Tsar in 1917. In the nineteenth century, the Holy Synod was ever more subordinated to the procurator, to the point that the procurator basically exercised control over the Russian Orthodox Church. This is why you’ll hear some people say that the Russian Orthodox Church was a “department of the state.”

After the February Revolution of 1917, the new Provisional Government in Russia authorized the convening of an All-Russian Council, which reorganized the governance of the Russian Orthodox Church and established a new institution – the new Patriarchate of Moscow – electing St Tikhon as the first Patriarch. This is analogous to what happened with the Patriarchate of Constantinople following the Ottoman conquest in 1453.

As the council was taking place, the October Revolution occurred, bringing the Bolsheviks into power. Under the new Communist regime, Russian Orthodoxy was harshly persecuted, and normal church administration was impossible. St Tikhon died in 1925, and there was no election for his replacement. Instead, in a very unusual ad hoc sort of arrangement, St Tikhon appointed three potential successors in his will, who could become locum tenens if necessary. Soon after Tikhon’s death, his appointed locum tenens was himself imprisoned, but he had drawn up his own list of potential successors. This left the Patriarchate nominally in the hands of Metropolitan Sergius Stragorodsky. On paper, the Moscow Patriarchate continued to exist, but in practice, it could not actually govern the Orthodox Church in what was now the Soviet Union. It basically had no functioning institutions. Its theological schools had long since been closed, and normal processes like councils and hierarchical elections couldn’t happen. Metropolitan Sergius hung onto the title locum tenens for years, but it was not a title that carried a lot of real-world authority.

That all changed during World War II. The war led Soviet dictator Josef Stalin to authorize the establishment of yet another institution called “the Patriarchate of Moscow.” In 1943, he allowed for a new patriarchal election to take place, along with the opening of theological schools and the printing of church materials. The Moscow Patriarchate was reborn, and Metropolitan Sergius was elected Patriarch. This, more so than 1917, really marks the beginning of the present-day Moscow Patriarchate as a functioning institution governing the entire network of ekklesiae known as the Russian Orthodox Church. For the Church of Russia, 1943 is analogous to the 1920s for Constantinople, when a new governing structure was formed, replacing the old but continuing to use the name of its precursor.

Throughout all these changes, the actual ekklesia in Russia (or centered in Russia), the “Russian Orthodox Church,” has never ceased to exist, but the government of that Church has changed in dramatic ways. 988, 1448, 1589-91, 1721, 1917, 1943 – all of these are key inflection points, when the government of the Russian Church changed its form. The ekklesia of Kiev and the broader network known as the “Russian Orthodox Church” may have its formal origins in 988, but its current governing structure – the present-day Moscow Patriarchate – was really born in 1943.

***

If you read the current Statute of the Russian Orthodox Church, you’ll see that the highest authority in that church (or, more properly, that network of local ekklesiae under the council of bishops that is chaired by the Patriarch of Moscow) is a body known as the “Local Council,” which is defined as a council consisting of the bishops of the Russian Church along with representatives of the clergy, monastics, and laity. It refers to the entire “Russian Orthodox Church,” which has parishes and bishops all over the world.

This use of the term “local” reflects the concept of the so-called “Local Church,” which has come to mean what I’ve been calling a “network of local ekklesiae” under a common authority. “Church of Antioch,” “Church of Romania,” “Church of Russia”… these are called “Local Churches,” with capital letters. Of course, there’s nothing really “local” about them; the title does violence to the meaning of the word “local” (in Greek, “τοπῐκός”). The Local Church now refers to ekklesia networks that can be utterly vast in scope, covering the globe and encompassing tens of millions of people (in the case of the “Local Church” of Russia, over a hundred million). And whatever the utility of this concept, as I’ve already said, there’s no question that it is not Apostolic. It is, rather, a byproduct of the administrative structure of standing synods of bishops that, in time, came to acquire the label “autocephalous” (about which, much more to come in a future article).

Please don’t read this and think that I am calling for the abolition of patriarchates or other administrative structures of the Orthodox Church. What I’m trying to do here is to disambiguate between concepts that have become confused – some Apostolic and unchangeable, some historically contingent and administrative in nature.

A “Local Church” is not a local church; it’s an administrative arrangement that has changed over time, dependent upon a common governing structure. And the governing structure of a church is not the church itself. Which means that a patriarchate or a holy synod is not a church.

St. Justin Popovich 1894-1979

…[T]he Orthodox Church, in its nature and its dogmatically unchanging constitution is episcopal and centred in the bishops. For the bishop and the faithful gathered around him are the expression and manifestation of the Church as the Body of Christ, especially in the Holy Liturgy: the Church is Apostolic and Catholic only by virtue of its bishops, insofar as they are the heads of true ecclesiastical units, the dioceses. At the same time, the other, historically later and variable forms of church organisation of the Orthodox Church: the metropolias, archdioceses, patriarchates, pentarchias, autocephalies, autonomies, etc., however many there may be or shall be, cannot have and do not have a determining and decisive significance in the conciliar system of the Orthodox Church. Furthermore, they may constitute an obstacle in the correct functioning of the conciliar principle if they obstruct and reject the episcopal character and structure of the Church and of the Churches. Here, undoubtedly, is to be found the primary difference between Orthodox and papal ecclesiology. (On a Summoning of the Great Council of the Orthodox Church)

If the administrative structure does not embody the church, at least in some true way, what is the point of metochia? I’ve always read that Orthodox ecclesiology is more eucharistic than hierarchic. Isn’t the purpose of a metochion to represent one autocephalous church to another, to establish that they are in communion with each other? What sense is there for administrative structures, that are not themselves the church in some way, to be in communion with each other? Maybe I’m misunderstanding something, but it seems to me that metochia implicitly acknowledge that patriarchates are true churches, not merely an administrative structure – even if that structure developed for purely practical reasons. Isn’t it through the network of autocephalous churches that individual bishops, and thus, complete local churches, know who they are in communion with and who they aren’t? Doesn’t it make sense, then, that there should be one bishop to whom all other bishops look to in order to know who is in the church, and with whom they are in communion? Administratively, the patriarchates and their synods function the same as the pope and college of cardinals; just at one rung lower down on the ladder. Would it be correct to say, then, that Orthodox ecclesiology is not either eucharistic or hierachic, but both/and?

Christ Is Risen!

Well said, Matthew.

I’ve been expressing concern about this exact issue for the past 15+ years, but, sadly, most Orthodox seem indifferent.

While both primacy & conciliarity are aspects of Holy Tradition that go back to the apostolic period, and there are bountiful examples of this working quite well, we also know there were periods in history when unOrthodox administrative structures were imposed upon the Church they were never accepted or defended by the ekklesia, and when the opportunity emerged for the Church to restore its authentic Orthodox structure/functions it was always done, as you pointed out.

However, now what appears to be dramatically different (starting ~100 years ago with Meletios Metaxakis) is that the very nature, structure & function of the Church itself is being reimagined & redefined via novel & idiosyncratic interpretations of Church history, theology & the canons, not only by the Patriarchate of Constantinople but also by the Patriarchate of Moscow & to a lesser extent other patriarchates.

Last time I checked this was the very definition of heresy, i.e., choosing a different theology over the truth reveled to the apostles & handed over from generation to generation to the present day. The tragic mess in Ukraine seems to be a clear manifestation of this.

Thankfully, it appears that a universal council of the Church is brewing, which I anticipate will address these willful & unwillful ecclesiology heresies that plague the Church today.

Hats off to you for your excellent work here!