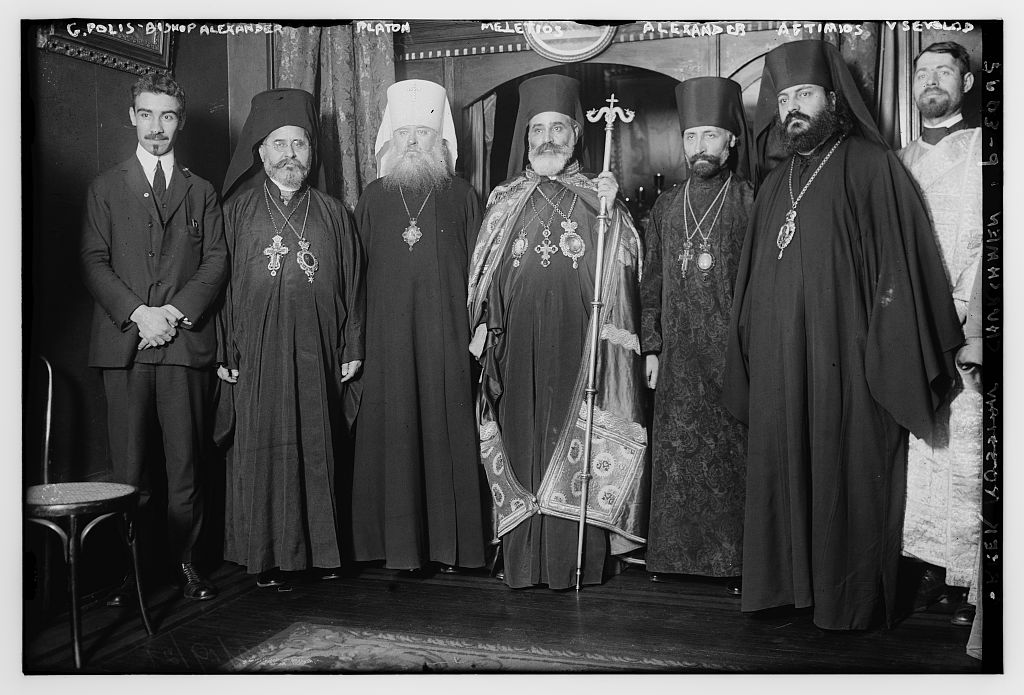

1921 gathering of Orthodox bishops. L to R: Germanos Polyzoides (future Metropolitan), Bp. Alexander Demoglou, Metr. Platon Rozhdestvensky, Abp. Meletios Metaxakis, Abp. Alexander Nemolovsky, Bp. Aftimios Ofiesh, Adn. Vsevolod Andronoff

The History of Orthodoxy in America in Two Words: Immigrants. Converts.

The History of Orthodoxy in America in Ten Words: Immigrants brought Orthodoxy and were joined by converts. Gradual acclimation.

The History of Orthodoxy in America in One Hundred Words (not including Alaska, I know): Orthodoxy took root in America at the turn of the 20th century when Orthodox people immigrated from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean and Eastern Catholics converted en masse to Russian Orthodoxy. Orthodox people generally set up their own parishes, obtaining priests from overseas. Besides the Russian parishes, they had little episcopal oversight. In the 1920s, these groups crystallized into ethnic “jurisdictions.” Ethnic groups split internally along political lines, but in recent decades some of the biggest splits have been healed. Most jurisdictions gradually Americanized and received converts, but additional influxes of immigrants have perpetuated the ethnic character of many jurisdictions.

The History of Orthodoxy in America in Ten Steps:

One: Following on the heels of Siberian fur traders, the Russian Orthodox Church began missionary work in Alaska (then part of the Russian Empire) in the late 18th century. Thousands of native Alaskans adopted Orthodoxy and integrated it into their culture, creating an indigenous Alaskan expression of the Orthodox faith that survives to this day.

Two: The Russian Empire sold Alaska to the United States in 1867. The first Orthodox parishes appeared in the contiguous United States in the late 1860s, mainly as outposts for the small numbers of Orthodox immigrants living in America.

Three: Orthodoxy in the contiguous United States (the “lower 48”) didn’t really get going until the 1890s. Two things happened simultaneously: (a) mass immigration of Orthodox people (mostly men) from Eastern Europe and the Mediterranean, and (b) mass conversion of Eastern Rite Catholics to Orthodoxy through the Russian Church. This boom period lasted for about 30 years, until the end of World War I and the imposition of immigration quotas in the 1920s.

Four: During the boom years, the typical pattern was for groups of Orthodox people to get some money together, start a parish, and hire a priest from the Old Country. The Greek parishes in particular had very little hierarchical oversight. The Russian parishes (mostly composed of converts from Eastern Rite Catholicism) were part of a fairly well-organized diocese of the Russian Church. The Antiochians, Serbs, Romanians, and some other groups had varying degrees connections to the Russian diocese, but also retained ties to the churches in their homelands.

Five: After World War I and the Bolshevik Revolution, all of the Orthodox ethnic groups in America experienced internal schisms and turmoil. The Greek Archdiocese was formed to unite the scattered, largely independent Greek parishes, but other, rival Greek jurisdictions also popped up. There were, at various times, four Antiochian jurisdictions, four Russian, two or three Greek, and two apiece for the Ukrainians, Serbs, Carpatho-Russians, Bulgarians, Albanians, and Romanians. The splits were often political, especially for ethnic groups from countries that now had Communist governments. There were lots of lawsuits over church property. It was a mess.

Six: Over several decades, most of those jurisdictional splits were healed (with the most notable exception being the Russians), and the jurisdictions crystallized into the ones we have today.

Seven: Often in conjunction with upheavals abroad (e.g., turmoil in Greece and Cyprus, civil war in Lebanon, and the fall of the USSR, among many others), successive waves of immigrants joined the existing jurisdictions over the past half century or so. This has contributed to many jurisdictions retaining an ethnic flavor that might have otherwise subsided after several generations.

Eight: The descendants of the original Orthodox immigrants became increasingly Americanized. They spoke English as their first language and many married people who were not Orthodox. As these descendants have become less tied to ethnic identity (and, consequently, the Orthodox faith that was so associated with ethnicity), many parishes have struggled to retain them.

Nine: In recent decades, American converts, mostly from Protestantism, have joined the Orthodox Church. Today, it is not uncommon to encounter Orthodox people who grew up in the Church but have no ethnic connection to Orthodoxy, because they are the children or grandchildren of converts.

Ten: The jurisdictions have talked about coming together to form a single Orthodox Church of the United States for decades, and particularly since SCOBA was formed in 1960 to bring together the heads of the jurisdictions for dialogue and cooperation. Numerous pan-Orthodox agencies and ministries have been established. In recent years, the “Mother Churches” mandated the creation of the Assembly of Bishops, which replaced SCOBA and includes all canonical bishops in America, rather than just the jurisdictional primates.

Bonus #11, which isn’t really history yet: In walking through our history, I’d be remiss if I failed to mention that, in the past decade or so, the biggest jurisdictions have been rocked by leadership crises of various kinds, often involving financial impropriety. But this isn’t really church history — these are basically current events.

(This article originally appeared on my now-defunct other blog, Notes on Church History, in 2014. It’s reprinted here with some revisions.)

Three point five: Late 19th Century mass immigration was accompanied by mass return migration (well over 50% for many communities at particular times), meaning that American parishes remained in a continual state of demographic flux, with many migrants maintaining affiliation with both old country and new world parishes, and with developments in regions of migratory origin and destination (for example, Eastern Catholic conversions to Orthodoxy) directly influencing one another well into the 20th Century. In other words, in the same way that American Orthodoxy had from its beginnings an “Old World” character, it’s possible to say that Orthodoxy in the Old World was very much “American” (and therefore, a part of the story of American Orthodoxy) by the turn of the 20th century. 🙂

May I repost this article on our parish website?

Yes, you’re welcome to repost it. Thank you for asking!