For centuries, the Orthodox Church in Georgia was autocephalous, with its own Patriarch (also known as “Catholicos”). In fact, for a long time there were actually two autocephalous Georgian Churches, one in the east and one in the west, each led by its own Catholicos-Patriarch. In 1783, the King of Kartli (the eastern kingdom) entered into a treaty with the Russian Empire. This was the beginning of the end of Georgian church independence. Initially, the Georgian Church was basically left alone, but the writing was on the wall. The Georgian Catholicos-Patriarch was made a member of the Russian Holy Synod. Russia did not have a patriarch in this era – the Patriarchate had been abolished by Tsar Peter the Great in the early 18th century and it wouldn’t be re-established until 1917. The Georgian Patriarch’s presence on the Russian Holy Synod was doubly weird: firstly, as a patriarch, he outranked all of the bishops on the synod, although he was treated as lower than many of them; secondly, if Georgia was really autocephalous and its primate a real patriarch, it made no sense for him to sit on the synod of a sister church.

In 1800, the last king of Kartli died, and the following year, Russia formally annexed the Georgian land. In 1811, the last Catholicos-Patriarch was forced to resign. He was replaced by an Exarch appointed by the Russian Holy Synod. The first Exarch was ethnically Georgian, but this was only a transitional thing; soon, all of the Exarchs were ethnic Russians, and the Russian church and state began to systematically suppress not only Georgian autocephaly but indigenous Georgian Orthodoxy altogether — Georgian as a liturgical language, the very unique Georgian chant tradition, the veneration of Georgian saints, etc.

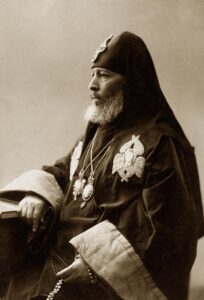

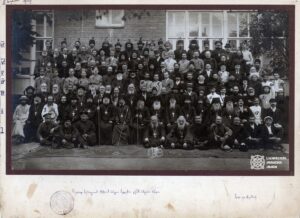

The next century was a painful one for Georgian Orthodoxy. In the wake of the February Revolution in Russia in 1917, the Tsarist government in the region collapsed. Georgian bishops and priests stormed the offices of the Russian-controlled Georgian Exarchate, replacing the Russian leadership with native Georgians. The new revolutionary government in Russia was ambivalent toward religion, creating an opening for the Georgians to restore their ancient church. In September, an All-Georgian Council was held in Tbilisi. The council declared the restoration of Georgian autocephaly and elected a new Catholicos-Patriarch, Kirion II. In response, in December 1917, St Tikhon, the new Patriarch of Moscow, sent a letter to the Georgians, rebuking them for their actions and calling on them to submit to the Russian Church. The recipient, Catholicos-Patriarch Kyrion, was assassinated in 1918 (he has since been canonized a saint). A year and a half later, August 5, 1919, the new Catholicos-Patriarch, Leonid, sent a scathing response to St Tikhon. Rather than accept St Tikhon’s rebuke, Leonid issued one of his own — over 7,000 words long, schooling the Russian Patriarch on the recent history of oppression of the Georgian Church.

Years later, in 1932, the letter from Leonid to Tikhon was translated into French and published in the journal Échos d’Orient, volume 167, pages 350-369 (click here for the complete French text). Thanks to Eric Peterson and Cassidy Irwin, we now have what I believe is the first English translation of that letter, the full text of which may be found below.

THE GEORGIAN CHURCH AND RUSSIA

A Letter from Catholicos Leonide to Patriarch Tikhon

Humble Leonide, by the grace of God Catholicos-Patriarch of All Georgia, to the Most Honored Lord and Most Dear Brother and Colleague in Christ, the Most Holy Tikhon, Patriarch of Moscow and All Russia.

“Remembering the faith which is so sincere in you and the charity coming from a pure heart and a good conscience” [cf. 1 Tim 5] which seeks the truth, the Georgian Church rejoiced in great joy when she received the news of your accession to the head of the Russian Church and the restoration of canonical order in this same Church.

However, upon receipt of your letter of December 29, 1917, No. 3, our great joy changed to deep sorrow. For we did not find there “the word of peace and charity” which characterizes you, but only the accusation leveled against the Georgian bishops who, you say, “having broken off all canonical relations with the Orthodox Church of Russia, acted hastily to wrest from the Provisional Government the Constitution of March 27, 1917, affecting the autocephaly of the Georgian Church. They thus broke the union of faith and charity with the Orthodox Church of Russia and ceased to communicate with it contrary to the canonical rules.”

Your Charity thus affirms: (1) “It has been more than a hundred years since Orthodox Georgia was united with Russia under a single ecclesiastical power,” and since then the supreme ecclesiastical power in Georgia “has belonged without question to the Holy Synod of Russia;” (2) for a century “such an order” aroused no opposition; (3) because of the attempts which were made in 1905, relative to the autocephaly of the Georgian Church, the [Russian] Holy Synod decreed in 1906 to submit the contested question to the examination of the next local council of the Russian Church; it is before this “tribunal” that we had to express our wishes and our aspirations concerning the Church and await its decisions.

Considering what has just been stated, Your Beatitude is not sufficiently informed about the reality of things, and I believe it my duty to present to Your Charity a word of pure historical truth concerning the Church of Iberia.

I

Orthodox Georgia, Your Beatitude affirms, united with Russia under one common ecclesiastical power, and since then ecclesiastical supremacy “has belonged unquestionably to the Holy Synod of Russia.” As Your Beatitude knows, more than a hundred years ago, martyred Georgia united with Orthodox Russia “under a single common political power,” but it then did not in any way or by any positive act manifest the desire to unite with it also ecclesiastically. Such ideas may have arisen among a few State officials, but the assembly of legitimate Church authorities was firmly resolved to preserve its ecclesiastical independence under these new conditions of civil life. The Holy Synod of Russia itself at first showed no desire to interfere in the affairs of the Georgian Church. This thought came first and entirely from the “secular officials,” who covered themselves with the name of His Imperial Majesty. To be clear: let us listen to the voice of history, this faithful mirror of events. The Ober-Procurator of the [Russian] Holy Synod, Prince Galitzin, having received from General Tormasof, Governor-General of Georgia, communications regarding ecclesiastical property, took advantage of these documents. He presented himself before the Emperor with an appropriate report and then wrote to Tormasof on September 28, 1810: “On this occasion the Emperor, taking into consideration that the [Russian] Holy Synod has no influence on the Georgian clergy, he is also ill-informed, and in order to better weigh the decisions to be taken on this question, asks Your Excellency to put you in touch with Archbishop Barlaam, formerly Bishop of Achtala, of the princely family of the Eristavs, who are now in Georgia, and then to explain, taking into account local circumstances, in what form, according to you, and on what basis should be organized the regime of the Georgian clergy so that it is placed in the dependence of the [Russian] Holy Synod.

General Tormasof, who, independently of Prince Galitzin, had begun to interfere in the affairs of the Georgian Church (from June 6, 1809) and who had sent, on November 3, 1810, the Catholicos Anton II in Russia, on February 18, 1811 (no. 28), presented to Prince Galitzin a project concerning the government of the Georgian Church, drawn up by agreement between himself, Tormasof, and the unpredictable and ambitious Archbishop Barlaam. According to this project, the Archbishop of Mtskheta was to be placed at the head of the Georgian Church and Kartli was to be placed as head of the Georgian clergy, with the title of “Metropolitan of Mtskheta and Kartli and Exarch of the [Russian] Holy Synod for Georgia.” He would be under the jurisdiction of the [Russian] Holy Synod, to which he would refer for the solution of cases of high importance and necessity and before which he would give an account of all the affairs that this same Synod would have prescribed to him.

In April, 1811, the Emperor Alexander I ordered the [Russian] Holy Synod to examine this project, and the Holy Synod, which this order so to speak “forced to meddle in the affairs of the Georgian Church,” prepared a report of full submission of the Georgian Church, and the presented it on June 21, 1811, to the Emperor, who sent it back to him with this decision signed in his own hand: “Let it be so.”

In this way, the suppression of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church is not “a voluntary union with Orthodox Russia,” but rather the work of representatives of “secular leaders.” However, Your Beatitude knows very well that the interference of lay leaders in ecclesiastical affairs is prohibited by the holy canons. They tolerated this interference only where the imperial power wanted to reduce the territory of the “true metropolitan” by the “foundation of a new city,” provided that this was done “without constraint of the old metropolis.” This tolerance finds its explanation exclusively in the fact that the Fathers, authors of these canons, did not have the opportunity to speak out against the imperial power.

The Holy Synod, as if it “dreaded contact” with the Georgian Church, held itself in an incomprehensible reserve for a historian of the Russian Church. And although it only expected ‘disappointments’ from these relations, it said nothing against the interference of the ‘civil agent’—General Tormasof—in the affairs of the Georgian Church. On the contrary, the Holy Synod took advantage of the opportunity and obtained episcopal power over the Georgian Church and thus violated the following canons:

1) “Let no bishop dare to pass from one eparchy to another nor ordain anyone in the churches (of another eparchy) for ecclesiastical functions, nor introduce there (for that purpose) anyone with him, unless he be summoned by a letter from the metropolitan and his bishops, into whose territory he intends to enter. If anyone, without being called on, dares, against any rule, to confer orders and govern the ecclesiastical affairs which do not depend on him, then all that he will have done is to be declared void, and he himself bear the deserved penalty for this disorder and this unreasonable enterprise: namely, that he be deposed by the holy council.”

2) “That the bishops of a region do not extend their power over the churches which are outside the limits of their region and do not confuse the churches. Unless called, bishops should not leave the diocese to confer orders or perform any other function of ecclesiastical ministry. If the rule above prescribed to the dioceses be observed, it is clear that, in conformity with the ordinances of Nicaea, the power of the synod of each eparchy will administer the affairs of the eparchy.”

3) “That one observes everywhere in the eparchies this rule that none of the very pious bishops has the right to encroach on another eparchy which was not formerly and from the beginning under the jurisdiction of his predecessors. That, if someone encroaches in this way and seizes an eparchy by force, he is bound to restore it, so that the canons of the Fathers are not violated, and to prevent, under the pretext of zeal, worldly pomp, and little by little, and imperceptibly, lose that freedom which our Lord Jesus Christ, the Savior of men, acquired for us by his blood. It therefore pleased the holy and ecumenical council to decide that the rights of each diocese which belong to it from the beginning must be safeguarded in their integrity and without any obstacle, according to the old custom. If someone opposes another rule to what has just been decreed, the holy and ecumenical council decides to declare it null.”

Therefore, despising the holy canons that we have just quoted, and putting on the breastplate of the “supreme commandment,” on June 10, 1811, the Holy Synod seeks “in a completely irreproachable manner” to secure from Emperor Alexander Pavlovich that, “condescending to the request of the Georgian Catholicos Anton, [the Emperor] has the great kindness to relieve him of the administration of ecclesiastical affairs in Georgia;” that the Georgian Church, without any decision taken by the assembly of its hierarchs, be submitted to the Synod of all Russia, and that at the head of this Church be placed the ambitious Barlaam, already Metropolitan of Mtskheta and Kartli, “with the title of member of the Holy Synod and Exarch of the same Synod in Georgia.”

It is in this way that the reunion of the Church of Georgia with Russia took place, Your Beatitude, “under a single common ecclesiastical power,” and Your Beatitude finds such a canonical union which conforms “to the word of truth and of charity”?

II

Your Clemency then affirms: “The union of Georgia with Russia under a single common ecclesiastical power provoked no opposition for a whole century”; “On the contrary, the Holy Synod possesses many documents emanating even from the Georgian people, which bear witness to the good result produced by its government in the Caucasian eparchies. According to the testimony of the Georgian clergy itself, in the person of the Most Reverend Kyrion, currently Catholicos of Georgia in his book A Historical Overview of the Georgian Church in the Nineteenth Century, the union of Georgia with Russia was a source of the efflorescence in Georgia of ecclesiastical life which had fallen into decadence.”

Venerable Lord, only the spirit which does not come from God could report to you that “for a whole century such a union provoked no opposition.” Is it entirely beyond your knowledge that “the people of Georgia could not resign themselves to the annihilation of the independence of their Church and its subjection to the Holy Synod,” that, according to the very words of Exarch Theophylact, “in the Georgian churches, the [Russian] Holy Synod was only mentioned in the Divine Liturgy when the presence of Russian agents was noticed,” and that it was in this loss of ecclesiastical independence that “we have to seek the main cause of all the periodic agitations that have arisen in the country.”

Does Your Beatitude ignore the “opposition” of the people and the clergy of Imereti under the leadership of two metropolitans, Dositheus (Tsereteli) of Kutaisi and Evktime (Shervashidze) of Gelatiwho, because of this “opposition,” were accused of rebellion against the imperial power, arrested without any form of trial and taken under a strong escort to Tbilisi, and then to Russia? A proof of the great importance attached to the “opposition” of the aforementioned prelates is found in the cruelty which the government of Orthodox Russia exercised against these two hierarchs of the Georgian Church. “So that the prisoners remain calm,” wrote Colonel Pouzyrevskij to Lieutenant-General Beliaminof, “and that they be deprived of all means of escaping or of recognizing each other and that they are not recognized by the population at their passage, I will place canvas bags over their heads with an opening at the height of their mouths, and I will attach them to their necks and belts. If necessary, I have resolved to kill them and throw their corpses into a river.” Such measures taken against the “opponents” did not satisfy Lieutenant-General Beliaminof. So, he recommended to his subordinate: “…above all, take care not to put to death the metropolitans, whose assassination could well arouse the population excited by the clergy and the nobility; murder would not even make a good impression on our soldiers, who, according to their belief, should hold the clergy in the greatest veneration. But if the killing of these old prelates becomes necessary (the general gave the order to do so on February 23, 1820), “we must not leave their corpses in Imereti, nor put them in the ground, nor throw them into the river, because the current could carry them away and reveal to the population who was killed. Don’t leave them in Georgia either. Transport them to Mosdok or at least to Caichaoura, where they can be left on the ground.” The chief’s order was strictly enforced, and one of these representatives of the “opposition,” the Metropolitan of Kutaisi , was strangled in a sack “on the road which leads from Surami to Gori.” For a long time, no one knew what to do with the body of the martyr bishop; they even hid him from the soldiers of the escort as far as Ananouri, where the order finally arrived from the [Russian] Synodal exarch of Georgia to bury the prelate without pomp and without ceremony.”

I believe, My Lord, that these texts taken from official sources testify quite clearly to the intensity of the “opposition” that Your Beatitude does not want to see in the history of the Georgian Church during the Synodal regime.

So as not to irritate your fraternal leniency by a detailed enumeration of other “oppositions,” I will only say that these “oppositions” were considered so dangerous by the Russian government that it was not afraid to admit it publicly. “It is time,” he said, “to put an end to the extraordinary influence which the clergy of Imereti exercises over the minds of the population. So, he had recourse to annihilate this influence by all means, by exiling to Russia all those who opposed the Synodal regime in Georgia.

At the sight of such treatment inflicted on members of the clergy who defended ecclesiastical independence, the nobles and peasants of Georgia gave free rein to their “opposition,” and here were their bitter complaints: After the violent abolition of the ecclesiastical independence in Georgia, “many holy churches are demolished, stripped of their venerable and illustrious icons and crosses, deprived of their priests who prayed for them and of the blessing of their bishops.” They then ask this question: “If we respect the belief of the blind Jews, the faith of the armed; why are we excluded from this blessing? If the Muslims, when we were under their power, did not touch our unshakable faith and did not throw us into such misfortunes, what crime have we committed now to have our bishops taken from us, to whom we were accustomed, our churches and our priests.”

Such measures taken against the “opponents,” some of whom even, according to General Tormasof, were devoted to the Russian cause (which they proved in many circumstances), threw fear and terror among the members and the ministers of the Church of Christ, and that is why, in the aftermath, one daringly proceeds to an open opposition. But, despite everything, a muffled indignation against the anticanonical situation of the Georgian Church did not stop rumbling. It was clearly reflected in the press and in private interviews with those in charge. We have enough evidence. However, I will only expose to Your Charity these simple facts.

On November 8, 1841, on a report from the [Russian] Synod for the appointment of a vicar-bishop in Georgia, Emperor Nicholas I wrote this annotation: “I consent, but in order to retain influence over the population, the knowledge of the native language being almost indispensable there, it is to be hoped that people who know the language will be chosen, even if they are not as well educated as is necessary here. Isn’t this concern of the emperor for the faithful of Georgia the result of the ‘protests’ that reached the ears of Nicolas Pavlovich? I omit the protests of Msgr. Gabriel, bishop of Imereti, around 1870 and 1880, against the exarch Eusebius and some civil figures (K. P. Janovskiy, M. R. Zavadskiv, Kerskij, etc.) whose policy aimed at transforming the Church into an instrument of Russification he condemned; against the persecution of the Georgians in the seminaries, the pillage of sacred objects, the appointments of Russian bishops and priests who were ignorant of the language of their flock and the customs and aspirations of the people.”

What can be said of the general discontent that reigned in the press and in society on the occasion of the seizure of the churches and monasteries of Bizvinta, Simon the Canaanite, Drandi, Mocvi, Saphara, Akhtala, and especially Bodbé, which houses the relics of Saint Nina, Equal to the Apostles and Illuminator of Georgia? Isn’t it all “opposition against the supreme Russian ecclesiastical power and its followers in Georgia?”

The exarchs of the [Russian] Synod themselves knew of these “oppositions,” which they heard with their own ears. But they explained all this by the incapacity of “judgment,” the “stupidity,” the “frenzy” of the Georgian people and their “passion for homicide.” This is how the famous hierarch of the Russian Church, the president of the Holy Synod, Msgr. Joannicius, formerly exarch of Georgia interpreted the “opposition” of the Georgians. As for his successor as exarch, Archbishop Pavel, in his correspondence with Archbishop Saba of Tver, he called his flock “savages,” and in a letter written in his own hand, he calls Georgia “a savage and ferocious country.” How “stupid,” “enraged,” “wild,” and “fierce” Georgians are, Your Beatitude can well judge by a glance, if only at the events of the last two years, a period of upheaval and general destruction. Georgia is the only corner of the ancient Russian Empire where the Hellenes and the Hebrews, the Scythians and the barbarians live peacefully without any fear neither for their life nor for their belief.

Thus, there is no foundation, my Most Venerable Lord, for your assertion that, for a whole century, the submission of the Georgian Church to the [Russian] Synod did not provoke any opposition from the Georgians. Nevertheless, I believe you when you say that the Synod has documents from Georgians which speak of the good result produced by the Synodal administration in Georgia. But these documents, believe me in your turn, come from people in some way interested and presenting the same characteristics as the sentence extracted by Your Beatitude from the work of Catholicos Kyrion, of eternal memory, and which its eminent author himself even retracted more than once. Moreover, we were then in such living conditions that it was almost impossible for us to write the truth. Let us also not forget that the venerable Kyrion did not and could not represent the Georgian clergy himself, since the opinion of this author of happy memory was always condemned by the Georgian clergy. The exarchs of Georgia themselves did not share it. Archbishop Platon, after having studied the situation of the Georgian Church, calls it fully tragic and the Church itself, a Church “running to its ruin.” These words of one of the most enlightened Russian hierarchs are very significant, because this last exarch made inquiries and appreciated the activity of his predecessors on the episcopal see of Georgia at the time of the Synodal regime in our country.

After this judgment passed by Archbishop Platon on the activity of the Synodal exarchs in Georgia, I flatter myself to hope that Your Beatitude will finally come to recognize that the affirmation concerning the good result produced by the Synodal regime in Georgia is not consistent with the truth.

III

“Because of the attempts which were made in 1905 for the re-establishment of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church,” writes Your Beatitude, “the Holy Synod decreed, in 1906, to submit ‘the said question’ to the examination of the next local council of the Russian Church;” it was before this “tribunal” that we had “to express our wishes and our aspirations relative to the Church,” and we had to “await its decisions.”

The facts described in the preceding paragraph should make Your Beatitude understand why “the attempts to reconstitute the autocephaly of the Georgian Church did not manifest themselves until 1905.” It was only in that year that it was officially allowed to tell the truth, and we told it. However, did “these attempts to re-establish the canonical order” occur only among us in 1905? The Russian Church, which nevertheless found itself in much better conditions than that of Georgia, but which, for more than two hundred years, had been crawling before “Patriarchs in frocks and uniforms, people without faith and public apostates,” did not the Russian Church itself raise, in this same year of 1905, its voice for the restoration of the patriarchy? Your Holiness has doubtless not forgotten the cry of anger of Pobedonostsev at the first attempts of the best Russian prelates to establish a normal organization in the government of their Church, nor the great embarrassment of the hierarchs after this outburst of the all-powerful minister? Furthermore, Your Holiness also disagrees with the truth on another point. It was not by decision of the Holy Synod that the question of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church was postponed for the consideration of the next local council of all Russia, but rather by the good pleasure of Emperor Nicholas II, in response to the petition of the Georgian bishops concerning the restoration of the Georgian Church in its rights of autocephaly. The Holy Synod even then made no provision for publishing this sovereign decision in its official organ Tserk. Viedomosti, and it was the Governor General of the Caucasus who communicated it to the Georgian bishops. Basically, this decree or decision or sanction of 1906 prepared for the Georgian Church an even worse situation. In fact, the planned council could not deal with settling the question submitted for its consideration. We find proof of this in the “responses” of the eparchial bishops, future competent members of the council. These answers either did not touch on the question or settled it in the negative; there were those who demanded that we be handed over to justice.

The question of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church did not have a better fate in the pre-Synodal session. The latter resolved it in the negative and proceeded to settle the ecclesiastical affairs of the Caucasus by giving its approval to one of the two projects that the Archpriest J. Vostorgof had just presented to it. This project, in the words of Professor Glubokovskij himself, “was not entirely irreproachable from the canonical point of view,” because it proposed to “create” on one and the same territory two ecclesiastical authorities in full competition and susceptible to wage war among themselves.

Given this disposition of the future members of the assembly and their active collaborators, was it possible to refer our wishes and our aspirations for independence to the court of the All-Russian Synod?

Your Beatitude perhaps thinks that “our desires for independence” could have found defenders in respect of the right in those who held in their hands the destinies of the Georgian Church after the act of good imperial pleasure of 1906? Much to our chagrin, we have too few official documents to know in what light the exarchs presented this question to the supreme ecclesiastical authority of Russia. But what is available to us is enough to characterize these so-called exarchs of Georgia. The first to appear among us after the act of imperial pleasure was Archbishop Nikon. Here is what he wrote on January 20, 1908, to Metropolitan Anthony, president of the Holy Synod: “The (Georgian) clergy have decided to introduce the Georgian language into the teaching of theology in seminaries and ecclesiastical institutes, but this is something inadmissible… However, if they are allowed to use Georgian in the teaching of theology, they must be logical to the end and in no way deviate from the principles of political government. We can therefore, as I write in my report to the [Russian] Holy Synod, withdraw from the Seminary, on the grounds of the use of the national language in education, the subsidies coming from the imperial coffers, as well as the rights which it conferred on its students as long as it was purely Russian. Then, contrite for their fault and crying out for mercy, the Georgians will renounce their national claims and beg us to give them back what they had. No ceremonies with these people!”

Was it possible, Venerable Brother, to hope from the author of these lines that he would collaborate in resolving in a positive way the question of the restoration of the Georgian Church in its rights of autocephaly?

Let us come to Archbishop Nikon’s successor, the most venerable Innocent. The clergy of Imereti had assembled to congratulate him on his appointment to the exarchate and had expressed the hope of counting on his cooperation in resolving in a favorable manner the question of the Church of Iberia [Georgia]. He answered them that he knew only the Russian Church, and not the Church of Iberia [Georgia]. His successor, Alexis II, on December 7, 1913, presented a report to the emperor in which he treated the Georgian Church’s attempts at independence as fanciful “drivel” by Georgian intellectual autocephalists. As for Archbishop Platon, he did accept from the assembly of the eparchial clergy of Georgia a petition concerning the autocephaly, and even promised the deputies to transmit it to Prince Nicolas Pavlovich, Imperial Governor of the Caucasus. But in reality, he kept it in his possession by making the clergy believe that it had been transmitted to its addressee.

My Venerable Lord, what we have just said suffices to make it clear how the Synod of the Russian Church was being prepared to resolve the question of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church, which was submitted to its judgment, and what solution could be given to it. A negative solution on the part of the Synod of the Russian Church would have engendered division and enmity and even conflict between the two Churches of Georgia and Russia, which we have never desired, nor do we desire today. That is why the Georgians who then dealt with ecclesiastical affairs began to declare openly that the Council of the Russian Church was not entitled to give a solution to the Georgian question, even after the imperial decision of August 11, 1906, and they proposed to do everything possible to prevent this All-Russian Council from “resolving the question formerly submitted to its judgment.”

All this well considered, we found ourselves in the presence of this alternative: either to remain under the power of the [Russian] Holy Synod and to request from it partial reforms without touching on the question of autocephaly, or to wait for favorable circumstances allowing the Georgian Church to re-establish its rights of independence. It pleased God to bring about such circumstances which enabled the Georgian Church to choose the second way. The result was the “Great Act” of Independence of March 12, 1917. And it is because of this that you condemn us, you, full of charity?

IV

However, O Most Blessed, you say, in continuing your accusation, that after having severed all canonical relations (namely, by the act of March 12, 1917) with the Orthodox Church of Russia, we acted hastily to wrest from the Provisional Government the Constitution of March 27, 1917, concerning the autocephaly of the Georgian Church.

Venerable Lord, it has pleased divine Providence to eliminate what stood in the way of the convocation of a council of the Russian Church until 1917, and all that had annihilated the autocephaly of the Georgian Church: the autocratic power gave way to representatives of the people. Faced with such a change, the bishops, the representatives of the clergy, and the faithful of Georgia found it opportune to meet in council on March 12, 1917, in the cathedral of Mtskheta dedicated to the Twelve Apostles, and to proclaim with one voice and one same soul the following act: “From this moment, the autocephalous organization of the Georgian Church is considered as restored. Notification will be made to the Provisional Government, successor to the power which abolished this organization in 1811, and which, in 1906, received the petition for his reinstatement.”

As for the Provisional Government, it was not under the pressure of the Georgian bishops, as Your Holiness wrongly supposes, but quite independently of us, that it issued its regulations of self-determination. In this settlement, the Provisional Government forbade itself from touching the canonical side of the re-establishment of the autocephaly of the ancient Church of Georgia: it touched on it, however, and resolved this question in an anti-canonical manner. The Provisional Government “attributed (in effect) to the autocephalous Church of Georgia a Georgian national character” omitting to assign to it, as required by the canons, territorial limits and leaving, contrary to these same canons, “all the parishes non-Georgian Orthodox, Russian, and others, under the jurisdiction of the Orthodox Church of Russia.” The Provisional Administration of the Georgian Church found this solution anti-canonical, and on the very day on which the regulation arrived by telegram (March 28), it protested in these terms: “To recognize in the Georgian Church a character of purely national and non-territorial autocephaly, something of which we find no example in history, is absolutely contrary to the ecclesiastical canons which bind all the Orthodox… The recognition of the autocephaly of the Georgian Church must be based on the territorial principle and extend to the limits of the old Catholic Church of Georgia. The Provisional Administration of the Georgian Church similarly included this protest in the draft “Fundamental Principles of the Canonical Position of the Georgian Church in the Russian State,” a draft signed by its members and by Professor Beneshevich, temporary delegate of the Provisional Government for Georgian Church Affairs. But the Provisional Government replied negatively to our just protest, finding it impossible for it to take into account the requirements of the ecclesiastical canons, and, in this way, sanctioned the phyletism condemned by the Church. Also, upon receipt of the “provisional rules of the canonical position of the Georgian Church within the limits of the Russian government” ratified by the Provisional Government, an extraordinary council of the Provisional Administration of the Georgian Church and all its eparchial divisions assembled and sent to Kartachef, on August 12, 1917, a protest in the strongest terms.

This account of events must make it known to Your Charity that, since the [Russian] Holy Synod, at the beginning of the nineteenth century, did not interfere in the affairs of the Georgian Church on its own initiative, but under the pressure of the sovereign power, the Georgian Church had a right to hope that the Orthodox Church of Russia, in the person of the Holy Synod, would feel a lively joy at seeing itself delivered from the worries and anxieties incumbent upon it concerning the Georgian Church and repair the fault committed by the Provisional Government. But that didn’t happen. Archbishop Platon, a member of the Holy Synod, officially notified by us of the restoration of the Georgian Church to its rights of autocephaly and of the consequent loss to him of his position as Archbishop of Kartli and Kakheti and Exarch of Georgia, far from congratulating us fraternally, went so far as to threaten us with Russian bayonets. For its part, the [Russian] Holy Synod hastened to adopt the same point of view as the Bulgarians, so justly qualified as schismatic by Your Holiness, and published, on July 14, 1917, the “Provisional Rules concerning the organization of the Church Russian Orthodox Church in the Caucasus,” which included the erection of the Russian metropolitan seat where, since the 5th century, there was the seat of the Georgian Metropolitan of Tbilisi, in blatant opposition to the 8th canon of the first ecumenical council which forbids having two bishops in the same city.

I hope, after all this, that Your Holiness will recognize, “in the depth of your intelligence,” may I say, that the Georgian bishops have always supported the canonical order, while those who called themselves the representatives of the Russian Church went against the holy canons.

V

Your Holiness also reproaches us for having destroyed the unity of faith and charity with the Orthodox Church of Russia and severing “all relations with her, contrary to the holy canons.” This reproach we have not deserved and, consequently, it has no foundation. Certainly, after March 12, and especially March 27, 1917, we no longer recognized the anti-canonical authority of the [Russian] Holy Synod over us, but we had no intention of “remaining outside of all relationship with the Russian Church.” The document delivered by us on March 14, 1917, to Archbishop Platon clearly stated that this prelate “lost the right of government” in Georgian eparchies and parishes, in seminaries, and ecclesiastical institutions as they were within the limits of the Georgian canonical territory, and this independently of any ethnic composition within the Georgian canonical territory, as well as in the rest of the country formerly subject to the Georgian exarchate. These canonical demands appeared unacceptable to the Committee of Russian Clergy and Laity of Tbilisi, formed around Archbishop Platon, and composed, above all, of the former companions of Archpriest Vostorgof. This Committee decided, on March 27, to bring to the attention of the [Russian] Holy Synod the following: “Considering as an accomplished fact the autocephaly of the Georgian Church, but not having the possibility of entering into the composition of the Georgian, Church, the Committee requests the [Russian] Holy Synod to create a Transcaucasian Exarchate subject to the [Russian] Holy Synod; this exarchate will receive into its bosom, regardless of any ethnic composition in the catholicate, as well as in the rest of the country formerly subject to the Georgian exarchate.”

From that moment, the Committee of Russian Clergy and Laity of Tbilisi affected with an anti-canonical element the relations of the two Churches, but we do not consider this action of the Committee of Tbilisi as violence against the children of the Russian Church who live outside the canonical territory of the Russian Orthodox Church, and that is why we have always recognized Archbishop Platon as the hierarch of the Russian Church outside the territory of the Georgian Church. We did not want, and do not want, to destroy the unity of faith and charity with the Russian Orthodox Church and break all relations with her. Your Beatitude can well see it in the following facts: at the opening of the Russian Synod of the Caucasus, which took place in Tbilisi, in the month of May 1917, we delegated our representatives in the person of a hierarch and a member of the Provisional Administration of the Georgian Church, to bring our greetings to the members of this assembly. In the month of June 1917, we sent a special delegation to offer our fraternal good wishes to the [Russian] Holy Synod. By its letter of June 28, the delegation begged the procurer V. N. Lvof to obtain permission for it to be received by the [Russian] Holy Synod, and the latter was pleased to fix August 1, 1917, as the day of reception. The [Russian] Holy Synod received the delegation in plenary session. Then the head of the delegation, Mgr. Antony, greeted the [Russian] Holy Synod in these terms: “High Holiness, Archbishops and Fathers divinely enlightened!” The sons of blessed Iberia, who since the time of the apostle Saint Nina, possessed the precious pearl of the Orthodox faith, and who in order to keep it have shed their blood for centuries, have resolved, at the end of the eighteenth century, to place the spotless dove in the custody of mighty Russia. Barely recovered after the union of Georgia with Orthodox Russia from the wounds that an enemy hand had inflicted on her, the Church of Georgia, our free and independent mother, was already gathering her children, like an incubator, under her wings, when, on the entreaties of the representatives of imperial power in Georgia, it was deprived of its leader and forcibly submitted to its younger sister, the All-Russian Church. The prayers and supplications which arose for the deliverance of the innocent prisoner were suffocated and even suppressed. Finally, when, on March 3 of this year, civil liberties were proclaimed in Russia, the people of the Georgian Church gave impetus to their desires and, on March 12, re-established their national Church in these rights of autocephaly. This act of “self-determination” was ratified by our provisional government on March 27 and July 25 of that same year and is called the “Great Act.” Bringing these facts to the knowledge of her beloved sister in Jesus Christ, the All-Russian Orthodox Catholic Church, in the person of Your High Holiness, the Orthodox Catholic Church and autocephalous Iberia sends his Christian greeting of sincere and ardent peace to his brother, the Russian people, who find themselves in the bosom of his Orthodox Church. Inspired by this lively feeling of charity in Christ, and remembering that the two Churches have kept in full agreement forever the holy dogmas of the Orthodox faith, the Cross-Bearing Church of Iberia expresses its firm conviction that from now on these two Churches, united between them by their belief and their aspirations, will live side by side in good harmony, in close ration and mutual love, so that they can speak, if not of the same language, at least with the same heart, the very sublime name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit. Christ is in our midst!

In the name of the [Russian] Holy Synod, our delegate replied to this greeting from the Archbishop of Finland, Sergius, president of the assembly. He did so in the following terms:

“The [Russian] Holy Synod implores God and it firmly hopes to be granted, that the Georgian people find in the new conditions of their religious and political life a source of new strength for their spiritual progress and for the maintenance without change of Christian truths. I need not remind you that the idea of restoring the Georgian Church to its primitive constitution has never been foreign to the consciousness of the Russian Church. And if this idea has not found its realization up to the present time, we should attribute it to particular causes which did not depend on us. It is with all the more joy that in these days of common liberating springtime this same conscience hastens to salute the fulfillment of your ancient dream. The [Russian] Holy Synod would also gladly do so; unfortunately everything happened in a somewhat unusual way and apart from the [Russian] Holy Synod, but we hope that God will arrange all things for the best, that the few asperities which appear in this matter will be ironed out; and that we shall meet fraternally at the next local council where, by common counsel, in a spirit of charity and Christian unity, we shall be able to find the enemy of mutual understanding so that our two peoples of the same faith, faithful to their ecclesiastical traditions, may live in peace side by side, each fulfilling his mission for the salvation of us all, to the glory of God!”

We too now hope, Most Holy Lord, “that God will arrange all things for the best” and “that the few rough edges which have shown themselves in this matter will be smoothed out.” However, if we do not meet fraternally at the local council of the Russian Church, the fault is not ours: despite the promise to the procurer, A.V. Kartachef, no one invited us “fraternally” to this council, which nevertheless did not fail to invite representatives of Churches of Constantinople, Greece, Serbia, etc. Be that as it may, Your Holiness cannot interpret our absence from the council as a desire to “stay out of all communication with the Russian Church.” For, in our dispatch read to the ecclesiastical synod of all Russia, on August 19, 1917, we greeted the opening of the work of the Council, and we asked the procurer of the Synod, Kartachef, member of the Provisional Government, to transmit to this Council, in the name of the Georgian Church, her fraternal salvation in Christ and her vows of fruitfulness in the great work of construction which fell to her.

After all this, Your Holiness’ invitation to us to appear before the All-Russian Holy Council and acknowledge any faults we may have committed is neither timely nor helpful: there are no faults in our conduct. If, against all expectation, there were any in the future, each Church has the means of extirpating them. Your Beatitude knows it. It is the “grace of the Holy Spirit, by which the priests of Christ see the truth with intelligence and preserve it with firmness.” For this reason, Brother, please do not, at the request of some, summon us to the tribunal of the Council of All Russia, “so that you do not appear,” in front of the Holy Church, “to want to introduce worldly pride into the Church of Christ.”

As for the rough edges of which the President of the Holy Synod, the most venerable Sergius speaks and which, in fact, exist both among you and among us, they were caused, more than a hundred years ago by the interference of civil agents in ecclesiastical affairs and the desire of the ruling [Russian] Holy Synod — a mere creature of the civil power — to keep the Georgian Church under its control. But you yourself know, O Most Blessed One, that all this “was done outside of ecclesiastical rule and under foreign impulse.” This is why, after the restoration of the canonical order in the Georgian and Russian Churches, we must watch firmly so that “nothing like this will happen again in the future.” And this is all the more possible and even necessary because, by the grace of God, “the old struggles are over and now everything has become new.”

With the renewal of ecclesiastical and civil life, we must also renew ourselves in our feelings for each other, “so that our two peoples, united by the same faith, being faithful to their traditions ecclesiastics, may live in peace, each fulfilling his mission for the salvation of all of us, to the glory of God.”

“May the grace of Our Lord Jesus Christ, the love of God the Father and the communion of the Holy Spirit be with us all. Amen.”

No. 3949

August 5, 1919

Tbilisi

Humble Leonide

Catholicos-Patriarch of all of Georgia