Editor’s note: The following article appeared in the Los Angeles Times on May 13, 1923, and was entitled, “Tolls Story of Old California.”

An old and battered bell, hanging in an orange grove where Ramona played in the days of her childhood, rang a new note in the song of California’s mission history yesterday.

After a silence of 127 years the ancient bell has spoken, and the tale it has told may alter certain chapters of the story of El Camino Real and prove facts of California’s history which in the past have existed only as theory. Further, it may refute one or two other phases of the King’s Highway chronicles which have always been accepted as a historical fact. It has been declared by several historians as one of the most important historical discoveries of a human interest nature ever made on the Pacific Coast.

Alice Harriman, noted campanologist and author, is accredited with uncovering the veiled past of the aged bell. Three years ago Mrs. Harriman first saw the bell as it swung in an orange grove at “Camulos,” where Ramona spent her girlhood days, and now the Del Valle ranch. Since then, she has devoted her time to tracing back the almost obliterated story of the bell. She announced yesterday the completion of her research work, in which she has been assisted by noted American and Russian authorities.

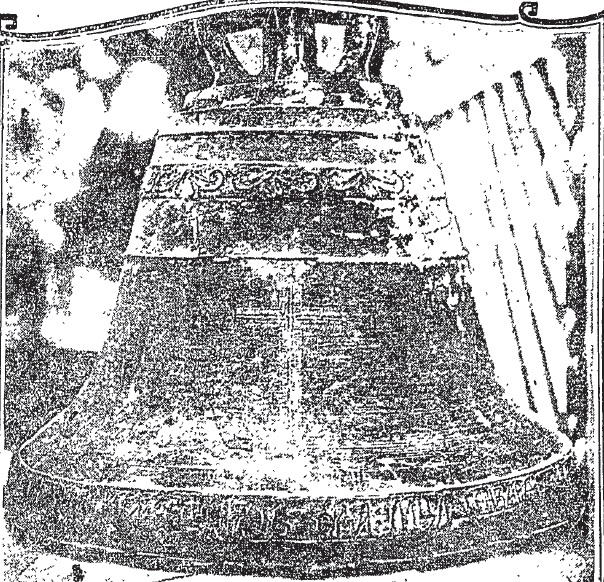

The bell is not of Spanish origin. Nor did it come to California from Mexico, Peru, Chili, Massachusetts or Russia — where almost all the famous bells of the world were cast. The Camulos bell was made on the island of Kodiak, Alaska, and presents the first glimpse into a phase of the earliest settlement of Russian America, now known as Alaska, which hitherto has been unknown to modern historians. The inscription on the Camulos bell, written in a forgotten language, betrays the secret. It reveals that it was cast at Kodiak in 1796 and that it was traded for food by Count Nicolai Resenov, one of the earliest settlers of Alaska, and that until sixty years ago it hung in the famed San Fernando Mission.

“I have found bells from Mexico, Spain, Peru, Chili, Belgium, Massachusetts, Sitka, and Russia,” said Mrs. Harriman yesterday, “but not until three years ago did I realize that I was to discover one of the most historical bells ever found.”

She told of a visit to Camulos when she first saw the bell in the orange grove. But the inscription was in Russian script. The Del Valle family knew little concerning the bell other than that it had been removed from the old San Fernando Mission to save it from vandals sixty-two years ago, and that ever since then it had been exposed to the ravages of the weather on Del Valle ranch.

A crude cross and a stenciled inscription “De Sn Ferno,” hammered on the bronze surface by the Franciscan fathers, proved it had once hung in San Fernando Mission.

Russian authorities could not translate the inscription around the lower rim. With the assistance of Dr. Herbert E. Bolton, noted historian, Mrs. Harriman learned that it was in the old Slavonic church language, now virtually extinct. She appealed to Rev. A.P. Kasheveroff, curator of the Alaskan Historical Society, and she learned portions of the inscription:

“Island of Kodiak — Alexander Baranoff — Month of January”

Two big gaps in the inscription could not be read from the photographs by Dr. Kasheveroff. She then sought the aid of Dr. Alexis Kall, of this city, a student of the forgotten language. The complete inscription read:

“1796 — In the Month of January, 1796, this bell was cast on the Island of Kodiak through the generosity of Arch-Mandrite Joasaph and elected church warden Alexander Baranoff”

Now, how did it get down into California, into an orange grove?” Mrs. Harriman asked. “Cast on a barely settled island with the wild, wide waters of the North Pacific pounding on the shores of the bay near where it was cast, by a Greek Orthodox arch-abbot for sponsor — how does it come that it was for years the bell for the Roman Catholic Franciscan Mission of San Fernando, in the lovely valley of the same name?

“The answer, almost certain and indorsed by historians and campanologists in California, Washington and Alaska, is that when Baranoff changed his headquarters from Kodiak to Sitka in 1805 he brough the bell with him.

“When Count Resenov visited Sitka and found the little settlement in such sore straights for food, he took the ‘Juno’ and came to California for food for starving Sitka. Knowing as the Russians did that the Spanish settlements of California had missions and that wherever there are missions bells are needed, Resenov brought this bell with other things that he thought he could exchange for the Southland’s grain and meat. When it was traded, the San Fernando inscription was stenciled on it.

“It may have been that the bell was brought by the Russians who hunted for otter on the Channel Islands; but bells are ungainly things to handle and it is doubted if there is any other explanation to be found than the one indorsed by those highest in authority on Pacific Coast history.

“The material in the bell also has an interesting history as research in Russian archives show. Baranoff wrote to Shelikoff, his superior in Russia and at whose instance the bell was first cast, that the copper he sent — meaning Shelikoff — had been received and that ‘that Englishman, Vancouver,’ had sent him some tin.

“Baranoff most fortunately, even wrote to Shelikoff revealing the name of the founder of this wonderful bell. It was Sapoknikoff.”

Mrs. Harriman stated that most of her positive information concerning the bell was found in Tekmeneft’s History.