Fr. Paul Kedrolivansky died on the evening of June 18, 1878, in the prison hospital in San Francisco, the victim of an apparent blow to the head.

Since December 1870, Kedrolivansky had been the dean of St. Alexander Nevsky Cathedral in San Francisco. In what must have been an awkward arrangement, his predecessor, Fr. Nicholas Kovrigin, became his assistant. Years later, a certain V.K. (possibly Deacon Basil – or Vasily – Kashevarov) said of Kedrolivansky, “Father Archpriest was continually occupied with keeping peace and quiet in the community with which he was involved. He was straight forward and even tempered, honest and not malicious. He was a benefactor to those in need, a true friend to his friends, reliable and trustworthy in his relations towards those with whom he served in particular and to all in general.”[1]

This near-saintly portrait of Kedrolivansky stands in contrast to the general picture of him during his lifetime. On May 27, 1877, the Ober-Procurator of the Holy Synod wrote this in an imperial edict to the Alaska Spiritual Consistory:

A member of the Spiritual Consistory in San Francisco and district dean, Archpriest Paul Kedrolivansky, can not be left in America any further since he has not cleared himself from the accusation of transporting contraband, brought upon him by the Alaskan Trade Company, as a result of which our Ambassador in Washington and our Consul in San Francisco declare it extremely necessary to remove him from America; and now he is being accused of incorrectly reporting the expenditure of sums allocated for the diocese.[2]

Just a note – if Kedrolivansky was recalled to Russia in May 1877, why was he still in San Francisco in June 1878? Was he blackmailing someone in a position of power?

Anyway, to his death: On the night of June 17 – a Monday – Kedrolivansky went drinking with his “roommate,” a fellow named Mindeleff, at the Tivoli Garden saloon. (Kedrolivansky was married and had a number of children, so it’s not clear why he had a roommate. Mindeleff could have been a boarder, I suppose, though later the claim surfaced that Kedrolivansky and his wife were separated. Years later, the San Francisco Examiner referred to Mindeleff and said, “he was a boarder of his,”[3] but I’m not sure who they mean when they say “he” and “his.” Was Mindeleff a boarder of Kedrolivansky, or the other way around?)

Around 10:00, Kedrolivansky was seen at Rosenthal’s tobacco shop, where he showed off a fancy-looking document and boasted that Fr. Nicholas Kovrigin would pay $10,000 to get hold of it. Apparently the document contained some incriminating evidence against Kovrigin, and Kedrolivansky was going to send it to the authorities in Russia. It would, so the story goes, spell ruin for Kovrigin’s career.

Kedrolivansky – who had a problem with alcohol – then moved on to another saloon, this one belonging to Joseph Blumberg. All these saloons and shops were in the same general vicinity, in what is today San Francisco’s financial district. He left the Blumberg establishment around a quarter to one in the morning. He was never seen conscious again.

Sometime between 12:45 and just before 2:00 AM, Kedrolivansky received a sharp blow to the head.

A little before two in the morning, Special Officer Stivers found Kedrolivansky unconscious outside of Eggers’ saloon at the corner of California and Spring streets. Stivers went off to get Kedrolivansky some black coffee in an effort to rouse him. The offices of the San Francisco Chronicle were at this same intersection, and while Stivers was away, a Chronicle reporter noticed Kedrolivansky on the ground and notified two other policemen, Brinkley and Hill, who deposited the priest in a hack and sent him to the city jail. He was wearing a hat; nobody noticed the head wound.

This wasn’t the first time that Kedrolivansky had been arrested for public drunkenness, and he was considered a “respectable drunk.”[4] After being booked and searched, he was handed over to a “trusty” and locked in a cell. Now, about these trusties – they were actually prisoners themselves, serving out their sentences, and they were given various responsibilities in the prison. Around 4:30 or 5:00 in the morning, Kedrolivansky was dragged out of his cell so that it could be cleaned. He was then returned; the whole time, he remained unconscious. At eight or nine – the reports conflict on this point – his assigned trusty figured that something must be wrong; drunk men don’t remain unconscious this long. So he called the hospital steward, who was just another trusty (and, as the Chronicle said, “knows as much about illness as the man in the moon”). The steward did feel Kedrolivansky’s head and noticed a “dent” in it, but he thought nothing of it and diagnosed him with mere intoxication.

At ten o’clock, the police surgeon visited the hospital. He left at noon; nobody told him about Kedrolivansky. Just after this, there was a shift change, and a new prison keeper assumed duty. He was apparently a bit more perceptive than his predecessor, and he took Kedrolivansky to the prison hospital and called for the surgeon to return. The surgeon, a Dr. Stivers (no apparent relation to Special Officer Stivers), bled Kedrolivansky, but it was too late. He never regained consciousness, and around 7:30 in the evening, he was pronounced dead.[5]

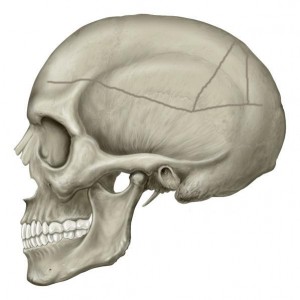

The location of Fr. Paul Kedrolivansky’s skull wound, based on the surviving portion of the autopsy report. Image courtesy of Richard Green.

Four days later, a coroner’s jury concluded that Kedrolivansky had been murdered by “person or persons unknown.” The newspapers immediately zeroed in on Kovrigin, for obvious reasons. The two men were rivals, and neither had a particularly good reputation. Kovrigin was apparently a scoundrel. In the same imperial edict which detailed the accusations against Kedrolivansky, there was this item on Kovrigin:

Sailor Wilson’s statement about a blameworthy liaison between a member of the Spiritual Consistory in San Francisco, Priest Kovrigin, and the wife of a certain Philip Kashevarov, must be investigated because of the gravity of the accusations detailed in this statement.[6]

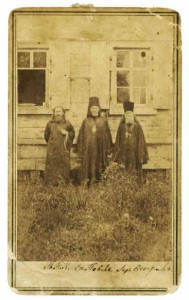

About a year later, in May 1879, Bishop Nestor wrote, “Right after beginning my administration of the Aleutian diocese I found myself forced to remove Priest Nikolai Kovrigin, who had become known, sadly, all over Russia for his deeds.”[7] In a report to Metropolitan Isidor of St. Petersburg the next day, Bishop Nestor said,

Upon my arrival in San Francisco, I heard verbal statements from many people and also from the clergy about all kinds of unseemly actions by the priest Nikolai Kovrigin. To protect the honor of Orthodoxy and to prevent all kinds of squabbles that badly reflect on the Orthodox Faith in foreign lands, I was, by necessity, put into the situation of relieving Kovrigin from his duty. […] Considering all circumstances, the future tenure of Priest Nikolai Kovrigin in America, because of many matters existing against him, will cast a shadow on Orthodoxy.[8]

Kovrigin seems to have had the most obvious motive to kill Kedrolivansky. More than the rivalry, there is the $10,000 document that Kedrolivansky displayed at Rosenthal’s tobacco shop. What was in that document? From the Chronicle:

Mr. Rosenthal, a tobacco dealer on Washington street, related that deceased had talked with him previous to the night on which he died, and had communicated the fact that he was afraid to be out late at nights. He had an important paper on his person which he was going to send to D.V. Petersburg [? – presumably the church or government authorities in St. Petersburg], and “that priest,” referring to his clerical assistant [Kovrigin], would give $10,000 to have it from him. The witness remembered that the dead priest had exhibited the document exteriorly. It was an impressive-looking document, long, and folded peculiarly in the center. The priest was somewhat under the influence of liquor at that time, as indeed, it appeared he was most of the time. Prisonkeeper Lindheimer remembered that when the man was brought into the Prison he had, among other papers, some document of that description, but there all account of it ceases. It appears to have vanished immediately, and a search among the Prison records failed to discover it.[9]

The document wasn’t the only thing missing from Kedrolivansky’s property. Apparently, a released prisoner was allowed to walk off with his silk hat.

The Russian consul in San Francisco, Vladimir Welitsky, told the Daily Alta California that the paper was related “to a divorce case, in which two subordinate priests were alleged to be concerned; the paper was written in English and translated into Russian, [to] be forwarded to St. Petersburg; the translation was placed in the hands of one of the priests, who failed to send it; a demand was made upon him, and he surrendered it to deceased.” Later in the same article, they report that Welitsky said that the paper “was only a translated copy of an affidavit, made by a lady in a suit for divorce… The affidavit contains charges against the moral character of a priest of the Greek Church.”[10]

From the Chronicle we learn that it was Welitsky himself who translated the document from English into Russian, and then “returned it to deceased for transmission to Russia.” Welitsky said “that some time ago an American gentleman had been divorced from his wife, who was a Russian lady and a follower of the Russian Church in this city, on the ground of adultery. It appeared that she had visited the deceased [Kedrolivansky] and his deacon [possibly Basil Kashevarov], and had written out a long explanation in English to the Home Government explaining the matter, and reflecting on Father Kovrigin, whom she accused of giving her pernicious advice in reference to married life. The matter was brought to the Consul for translation and it was translated. He endeavored to induce the priests not to send the document home and to refrain from indulging in such gossip, but they refused, and the paper was given to the deceased. The Consul retains the English copy. He stated that there was nothing in the document which could injure Mr. Kovrigin in the estimation of the home Government. He admitted that there had been some ill-feeling between the priests. He could conceive of no motive for murder.”[11]

Welitsky was adamant that the document was not damaging to Kovrigin. This is difficult to understand. Kedrolivansky, Kovrigin’s enemy, certainly considered it damaging. And anyway, how do we know the “$10,000 document” is the same as the document Welitsky referred to? We’ve only got Welitsky’s word for it. It’s possible that Kedrolivansky was boasting to Rosenthal about another document entirely, one which was even more damaging to Kovrigin.

As I noted above, Bishop Nestor sent Kovrigin back to Russia as soon as he (Nestor) arrived in America in 1879. The reasons for this, however, seem to have more to do with Kovrigin’s reputation as a philanderer than any suspicion that he was a murderer. Only a few days after the coroner’s jury gave their verdict, the following note appeared in the San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin:

Detective Jehu, who has been making inquiries into the cause of the death of the late Paul J. Kedvolivansky [sic], the arch-priest of the Greek Church in San Francisco, reported to have been murdered, reports that he has found several persons who saw the deceased fall on the sidewalk at the corner of Spring and California streets, a few minutes before he was discovered by the arresting officer. It is deemed certain that his death was caused by injuries received in the fall.[12]

Jehu’s findings are detailed in letter written by Police Chief John Kirkpatrick to Welitsky on June 25. Three witnesses swore that they had seen Kedrolivansky fall, and that he had “violently struck the back of his head against the stone curbing.”[13]

That seemed to close the case, and what looked like a sensational murder just days before was now transformed into a run-of-the-mill drunken, accidental death. I’m not entirely convinced, though, and neither were the Russians in San Francisco. After the June 22 inquest, one newspaper reported, “The Police Surgeon, Dr. Stivers […] thought that the fracture might have resulted from a fall, but deceased would have had to fall upon his side in a peculiar manner; the fracture might have been caused by a blow; it could not have been caused by a slung-shot or sand-bag.”[14] While the coroner’s report has not survived (it was burned in the fire that followed the 1906 earthquake in San Francisco), sections from it were reprinted in the newspapers. I’ll reproduce a description of the head wound in the endnotes.[15]

Leaving aside the three witnesses found by Detective Jehu, this looks like an obvious murder. Kedrolivansky had a known enemy, Kovrigin, who had, among other motives, the immediate concern of the “$10,000 document.” But Kovrigin isn’t the only suspect. Years later, the name of an otherwise unknown man named Amosov came to the surface. One newspaper, in 1891, reported the rumor that this Amosov had been hired by Kovrigin to kill Kedrolivansky.[16] Around the same time, Bishop Vladimir (the Russian bishop in San Francisco from 1888 to 1891) also mentioned Amosov (calling him a “nihilist”), saying that he had been hired by “the Jews” of the “notorious Alaska Company,” and had killed Kedrolivansky with a sandbag.[17]

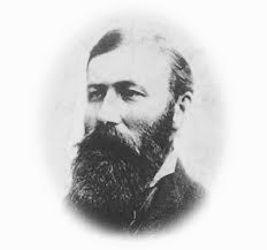

Again the Alaska Company. This organization, the Alaska Commercial Company (ACC), is the same one that accused Kedrolivansky of “transporting contraband” a year before his death. The ACC was headed by Gustave Niebaum, a native of Finland, which at the time was a part of the Russian Empire. At sixteen, Niebaum became a cabin boy for a ship of the Russian American Company. By twenty-one, he was captain of his own ship for the Company, and he became an expert sailor and trader in Alaska. After the sale of Alaska in 1867, the Russian American Company was divided between two U.S. companies, one of which included Niebaum.

In 1868, Niebaum arrived in San Francisco with half a million dollars’ worth of furs. The same year, the two U.S. companies merged to form the ACC, of which Niebaum was a partner. He eventually became the head of the company. He married into an elite San Francisco family, and just after Kedrolivansky’s death, he started a winery in Napa Valley. This winery was extremely successful; it produced Inglenook wines, and many decades later it was purchased by Francis Ford Coppola.

A year after Kedrolivansky’s death, Niebaum became Welitsky’s vice-consul. Welitsky promptly returned to Russia, leaving Niebaum as the acting Russian consul in San Francisco. In the late 1880s, during Bishop Vladimir’s tenure in America, Niebaum again served as acting consul. Given that he was the head of the ACC and was close to the Russian authorities in San Francisco, it’s reasonable to assume that Gustave Niebaum was involved in the 1877 accusation made by the ACC against Kedrolivansky.

Kedrolivansky left a family. His wife Alexandra was pregnant with their sixth child at the time of his death, and the child was born in September 1878. As Kedrolivansky was a Russian subject, his widow was entitled to a pension from the Russian government. A certain Mrs. Goodall, who worked for the Ladies’ Protective and Relief Association, appealed to acting consul Niebaum on behalf of Mrs. Kedrolivansky. Niebaum apparently told Mrs. Goodall that Mrs. Kedrolivansky was “a bad woman,” and he “advised Mrs. Goodall to have nothing to do with her, and further asserted that [she] had not lived with her husband for two years previous to his death, and that it was owing to her action that her husband took to drink, and while in a state of intoxication fell and was killed.” The clear implication was that Mrs. Kedrolivansky “had deserted her husband and had, previous to his death, led a dissolute and unchaste life, and became enceinte [pregnant] while living apart from him.”[18]

Alexandra Kedrolivansky denied all of this, and in 1881, she sued Niebaum, charging defamation of character.[19] Five years later, the Supreme Court of California ruled in her favor.

Niebaum certainly didn’t get along well with Fr. Paul or Alexandra Kedrolivansky. His predecessor and colleague, Welitsky, seemed particularly anxious to deny that Kedrolivansky’s death was a murder, even before any witnesses surfaced. I don’t think I can go so far as to call the two Russian officials suspects, but they did at least behave suspiciously.

Two points:

- The surgeon who examined Kedrolivansky said that he was probably struck by another person with a blunt object. He said that a fall was unlikely, as it would have to have been at an awkward angle. The surviving description of the wound seems to support this. Basing their decision on the surgeon’s testimony, the coroner’s jury declared the death to be murder.

- By June 25, the police found three witnesses who testified to seeing Kedrolivansky fall and hit his head on the ground at California and Spring streets. Basing their decision on this testimony, the police declared the cause of death to be an accidental fall.

These are two apparently contradictory sets of facts. Since the fact of the doctor’s testimony and the fact that the police found three witnesses are both equally true facts, we must find some way to reconcile them. How could they both be true? Let’s see…

- The surgeon could have been mistaken. This is rather unlikely.

- The witnesses could have been lying. How could this be the case? They could have been induced to lie by either the actual killer or some other powerful agent. I’m thinking of either the Russian consulate or the Alaska Commercial Company.

- Then again, what if both the surgeon and the witnesses were correct? It could be that, however unlikely, Kedrolivansky actually did fall in a very awkward way. After all, the surgeon did say that it was possibly a fall.

- There’s another way they could both be correct: Kedrolivansky could have been struck by a murderer, regained consciousness, stumbled about, and finally fell at California and Spring. Thus he would have been murdered, but the witnesses would have still seen him fall.

- It’s possible that he was pushed to the ground, and that somehow the witnesses only saw the fall and not the push. Along the same lines, he could have been hit and then fell, but the witnesses only saw the fall.

- Finally, it could be that the witnesses did see Kedrolivansky lying on the ground at California and Spring. Perhaps they were drunks, and their memory of the night was not entirely clear. A detective came around to the saloon to question them, and they had already heard about the death in the papers. They convinced themselves that they had seen him fall, when in fact they had only seen him fallen.

If you ask me, the best possibility is number four: Kedrolivansky was murdered, but the witnesses only saw him stumble about and fall.

Some other considerations… One thing that confused me was the question of the “$10,000 document.” There’s reason to believe (from the prison keeper’s testimony) that Kedrolivansky had the document when he was taken to prison, and that sometime after that the document disappeared. Another prisoner took his silk hat, so it’s entirely possible that the document was misplaced in a similar way. Anyway, assuming he did have the document when he was taken into custody, and assuming he was murdered, one immediately wonders why the murderer didn’t take the document with him. It could be that the murderer didn’t care about the Kovrigin document – that Kedrolivansky was killed not because he was agitating against Kovrigin but because he was a threat to the Alaska Commercial Company. The more I think about it, though, the more I think that the killer probably didn’t even know that Kedrolivansky had the document on his person. All he had to know was that Kedrolivansky was a threat. He was probably a hired hand, and he was told to kill Kedrolivansky. He never would have thought to search his person for papers.

As with many mysterious deaths, we must leave this one ultimately unsolved. There is no smoking gun, so to speak, no solid evidence one way or the other. All we can say for certain is that Kedrolivansky was a man with enemies, and that his death smells like a murder. Alas, it was just one in a serious of scandals which would rock the San Francisco parish in the years to come.

Endnotes

[1] Fr. Sebastian Dabovich, “The Orthodox Church in California,” Russian Orthodox American Messenger 15 (April 1-13, 1898), 455-460 and 16 (April 15-27, 1898), 479-482.

[2] “The Edict of His Imperial Highness the Autocrat of All Russia, from the Most-holy Governing Synod to the Alaska Spiritual Consistory,” signed by Ober-Secretary A. Polonsky (May 27, 1877), translated from the Russian and first published in Holy Trinity Cathedral (San Francisco) LIFE 4:9 (May 1997).

[3] “The Russian Church,” San Francisco Examiner (May 23, 1889).

[4] “Mysterious Murder,” San Francisco Chronicle (June 23, 1878).

[5] My main sources for this chain of events are the local newspapers. The June 23, 1878 Chronicle article cited above was very helpful. Other articles include the following: “Was a Russian Priest Murdered?” Daily Alta California (June 23, 1878), 1; “The Municipal Hades,” San Francisco Daily Examiner (June 24, 1878); and “The Late High Priest,” San Francisco Daily Morning Call (June 23, 1878).

[6] “Edict” (May 27, 1877).

[7] Bishop Nestor letter (May 20, 1879), in George Soldatow, trans. and ed., The Right Reverend NESTOR, Bishop of the Aleutians and Alaska, 1879-1882. Correspondence, reports, diary, Vol. 1 (Minneapolis: AARDM Press, 1993), 54.

[8] Bishop Nestor to Metropolitan Isidor (May 9/21, 1879) in Soldatow, 40ff.

[9] “Mysterious Murder.”

[10] “Was a Russian Priest Murdered?”

[11] “Mysterious Murder.”

[12] “The Cause of the Arch-Priest’s Death,” San Francisco Daily Evening Bulletin (June 26, 1878).

[13] John Kirkpatrick to W. Waletzky [sic] (June 25, 1878). This letter has been preserved in the archives of the Imperial Russian Consulate in San Francisco, which have been microfilmed by the National Archives in Washington, D.C. I am indebted to Dr. Terence Emmons for providing me with a copy.

[14] “Was a Russian Priest Murdered?”

[15] “The autopsy disclosed the fact that the scalp of deceased was very thick and strongly adherent, and on the whole of the left side there was a large amount of suffused blood. On the left side was found a fracture of the skull, commencing in the temporal bone, running upward and slightly backward into the parietal bone, being three inches in length; thence at right angles backward half an inch; thence downward and slightly backward two inches; thence at right angles forward one and three-fourth inches intersecting the first line described, leaving a detached piece pressing upon the brain. This portion of the skull was quite thin. From the point of intersection there was a fracture running across the temporal bone and ending in the median line of the frontal bone at a distance of about four and a half inches. There was also a fracture from the lower corner of the detached piece running backward across the parietal bone a distance of about half an inch. The brain directly under the fracture was lacerated and a brain clot weighing four ounces was found. The brain was in a healthy condition.” This comes from the San Francisco Examiner article “The Russian Church,” cited above.

[16] “A Dramatic Church History,” San Francisco Examiner (June 13, 1891), 3:1.

[17] Bishop Vladimir, quoted in Terence Emmons, Alleged Sex and Threatened Violence: Doctor Russel, Bishop Vladimir, and the Russians in San Francisco, 1887-1892 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1997), 109.

[18] Kedrolivansky v. Niebaum, 70 Cal. 216 (Supreme Court of California, July 27, 1886) in Pacific Reporter, 641-643.

[19] “A Russian Priest’s Widow,” St. Louis Daily Globe-Democrat (August 20, 1881), 3.

Lord have mercy!